Case

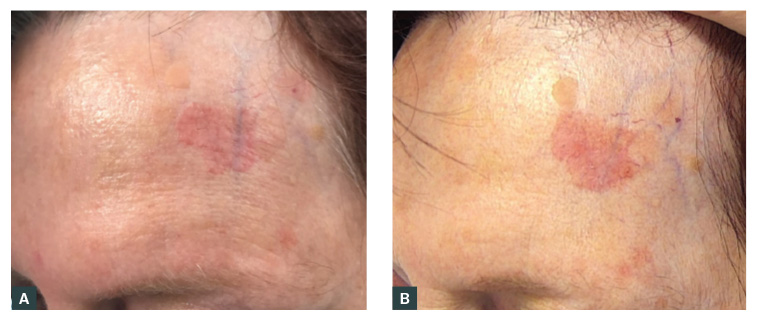

A woman, aged 71 years, presented for a routine skin check. Her past history includes a 0.5 mm Breslow thickness melanoma on her upper back 11 years prior, managed by wide surgical excision. There have been no further sequelae for that lesion. She has had other keratinocyte cancers removed in the past and has used 5% 5-fluorouracil and cryotherapy to manage actinic keratoses on sun exposed areas. A pink plaque on her left forehead was noted to have enlarged compared to previous clinical images (Figure 1). The lesion was not tender or bleeding, and she suspected that it was one of many that had previously been treated with cryotherapy. The lesion was no more significant to her compared to other areas of scale on her face and hands. Of note, she also had significant rosacea, controlled with topical metronidazole or ivermectin and occasional courses of doxycycline.

Figure 1. The lesion in (a) March 2022 and (b) March 2023, demonstrating the gradual increase in size over a 12-month period.

Question 1

What is your preferred diagnosis for this lesion?

Question 2

What differential diagnoses do you consider?

Answer 1

Given the slow growth over years, the consistent thickness of the plaque with well-defined edges and the lack of soreness or induration, a clinical diagnosis of intraepidermal carcinoma (IEC, Bowen’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) was preferred over SCC.

Answer 2

SCC was the most important differential diagnosis considered because of the potential consequences and the influence on treatment options. The area was too large for an actinic keratosis (solar keratosis). The amount of scale and lack of other dermatoscopic features made basal cell carcinoma unlikely. Other benign considerations would include a plaque of cutaneous lupus, a dermatophyte infection, an irritated seborrheic keratosis or chronic inflammation related to rubbing or trauma.

Case continued

A shave biopsy was taken, which confirmed the suspected clinical diagnosis of IEC. Treatment options were then discussed with the patient. Of significance, the patient resided two hours from the clinic and preferred to avoid frequent travel. She is otherwise well and her current medications are topical ivermectin for her rosacea. She does not take any blood thinning medications or herbal remedies for circulation.

Question 3

What is your preferred treatment for this

20×23 mm patch of IEC on her left forehead?

Question 4

What other treatment options do you consider reasonable in her circumstances?

Answer 3

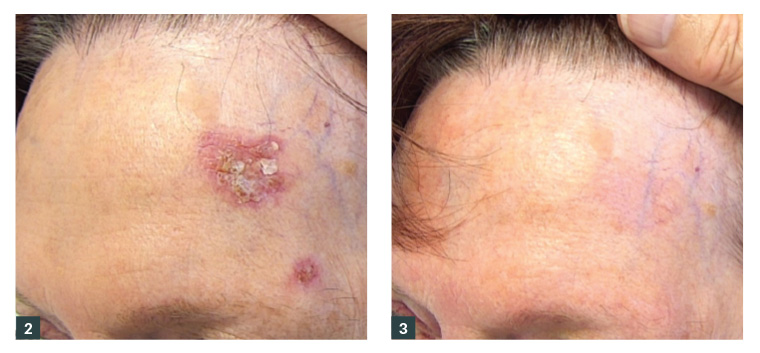

Surgical removal was offered and declined by the patient. Closure of this large defect would require a skin graft or large skin flap.1 The risk of the lesion having areas of SCC was discussed and the patient elected for a four-week topical treatment with 5% 5-fluorouracil.2 One concern was her underlying rosacea and the tendency for her skin to flush. She was started on 100 mg of doxycycline for seven days at the same time as commencing 5-fluorouracil to try and mitigate a flare of her rosacea. The topical treatment was started twice daily for seven days and then decreased to a daily application once the plaque had started becoming red and inflamed. She was then reviewed in the clinic after three weeks of treatment (Figure 2), where her reaction was considered appropriate. Therefore, a further one week of daily treatment was continued as planned. Her rosacea did not flare during the treatment period. On completing the four weeks of therapy, she was asked to apply moisturisers liberally until the scale had peeled from the plaque. A review of the area at six months did not identify any residual lesion, and the patient was satisfied with the cosmetic outcome (Figure 3). As expected, the adjacent seborrhoeic keratosis did not react to 5-fluorouracil.

Figure 2. Lesion after 3 weeks of treatment with 5% 5-fluorouracil.

Figure 3. No residual lesion evident clinically at 6-month follow-up.

Answer 4

Radiotherapy is also a good approach for this type of lesion, but this was not a practical option for this patient due to the distance for her to travel for treatment. More recently, a topical radiotherapy paste had become available, but this was declined by the patient due to price. Other topical therapies to consider include imiquimod, diclofenac and photodynamic therapy.3 Cryotherapy or surgical management with curettage and cautery can also be considered for areas of IEC,4 where healing is by secondary intention. A potential risk of more superficial treatments, such as cryotherapy or curettage, is that IEC can extend down hair follicles, leading to incomplete removal of the lesion.

Final comments

When using topical options for treating low-grade lesions, it is important to inform the patient about possible treatment failure and the need to have a surgical or radiotherapy intervention if the lesion recurs. These lesions also require prolonged follow-up as recurrence might not be evident for several years. Patient factors such as cost, distance of travel and personal anxieties or experiences should be considered when discussing treatment options.

Key points

- Management of low-grade skin tumours offers options other than excision.

- The patient’s situation and concerns should be considered in making treatment decisions.

- Careful follow-up is required for many years to monitor for incomplete treatment