Case

A woman, aged 77 years, contacted her general practitioner (GP) by telephone in October 2020 because of vulvar pruritus and painful vaginal fissures. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, consultations in our unit with all patients, if possible, were done over the phone. In this particular case, just one consultation, the first one, was by phone. The patient was treated with a single oral dose of fluconazole 200 mg and topical isoconazole for a presumed fungal infection. She was advised to return in person if there was no improvement. Three weeks later, she visited her GP because of a painful, unhealed ulcer. Examination revealed a vulvar ulcer of 1 cm × 1 cm replacing the clitoris. Vulvar atrophy with obliteration of the labia minora was also seen, along with white glazed patches on the vulva alternating with hyperpigmented areas of the skin (Figure 1) and glazed erythema of the vagina (Figure 2). The patient had experienced prolonged (~30 years) vulvar dryness, pruritus and dyspareunia. Menarche was at age 14 years, with regular cycles. She had five normal pregnancies with five vaginal deliveries. She had a hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy at age 42 years for uterine myomas. She had not received hormone replacement therapy. She had also undergone excision of lichen planus from the buccal mucosa with subsequent gingivitis.

Figure 1. Vulvar ulcer replacing the clitoris with loss of the architecture of the labia minora.

Figure 2. Glazed vaginal erythema with inferior restriction of the introitus.

Question 1

What is the differential diagnosis of the vulvar lesion?

Question 2

What additional background information might be relevant to help make the diagnosis?

Answer 1

Ulcerative lesions of the vulva are uncommon. Infectious causes include herpes simplex virus in immunosuppressed patients and primary syphilis in any patient. Among non-infectious aetiologies, ulcers can appear in acute vulvar aphthous conditions or might be due accidental or iatrogenic trauma. Less commonly, they can appear related to malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or melanoma, in Crohn’s disease and with hidradenitis suppurativa.1

Vulvar cancer (VC) typically presents with an ulcer, lump or mass associated with pruritus. Other symptoms include vulvar bleeding, pain, dysuria and vaginal discharge.2,3

Answer 2

In a patient with a vulvar ulcer, it is important to ask about the evolution of the ulcer and associated symptoms of pain, burning, pruritus, dyspareunia and dysuria, as well as other mucosal involvement. Inquiring about other concomitant conditions and the use of topical treatments is also important.1

Vulvar pruritus is common in vulvar dermatoses such as vulvar lichen sclerosus (VLS) or vulvar lichen planus (VLP). Both result in distortion of the vulvar architecture but show differences in the pattern of lesions, pigmentation and vaginal involvement.4,5 There is an increased risk of VC for women with VLS, but the association with VLP is not clear.6,7 VC arising from VLP is rare, but might exhibit more aggressive features.8,9

Other risk factors for VC should be investigated. These include vulvar or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, a history of cervical cancer, obesity, smoking and immunodeficiency syndromes.10

Case continued

An urgent referral to oncology was requested for a suspected malignancy. The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of vulvar SCC not related to human papillomavirus (HPV). Within six months, the ulcer grew to 7 cm in diameter with inguinal adenopathy of 7 cm. The patient was admitted for a radical vulvectomy, bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy.

Question 3

What is necessary to establish the diagnosis of VC?

Question 4

What is the appropriate management of this condition?

Answer 3

VC is a histological diagnosis, based on a biopsy of a vulvar lesion.

There are six main histopathological types: SCC, melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, Bartholin gland adenocarcinoma, sarcoma and Paget’s disease. More than 80% of VCs are vulvar SCC. The two subtypes are those not related to HPV, found mainly in older patients, and the classic type, associated with HPV types 16, 18, 31 and 33, found mostly in younger patients.2,3

Answer 4

The treatment of vulvar SCC depends on local extension to surrounding structures, lymph node invasion and comorbidities. Surgical resection is the main approach, through radical local excision or radical vulvectomy. Adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiation is given with lymph node involvement and metastatic disease. With unresectable lesions and locally advanced disease, chemoradiation is the principal approach.11

Case continued

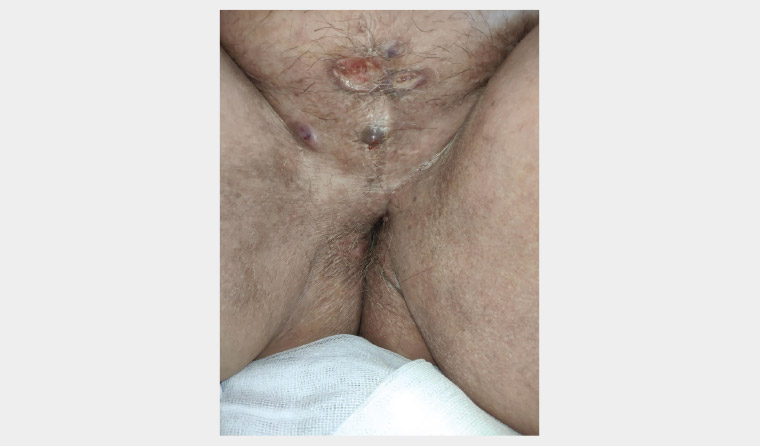

Due to postoperative complications, the patient did not receive radiotherapy. Five months after surgery, local relapse was observed (Figure 3). Further investigation revealed lung and bone metastases.

Figure 3. Local tumour relapse with multiple fistulous orifices and serous drainage.

The patient and her family were followed closely by her primary care team. Home care included dressing the wound and control of symptoms.

Key points

- VC is a relatively rare gynaecological malignancy. SCC is the most common histological type.

- A vulvar lesion such an ulcer, lump or mass with a history of vulvar pruritus is highly suggestive of VC.

- Vulvar SCC associated with lichen planus, although rare, exhibits aggressive features.