Among the prominent consequences of ageing are the physiological and morphological changes to skeletal muscle, resulting in an involuntary loss of muscle mass, strength and function.1 Muscle mass and strength begin to decline from 30 years of age, accelerating after 50 years of age,2 resulting in a loss of approximately 20% in muscle mass and 40% in muscle strength from their peaks in early adulthood.2 Physical function decline accelerates after age 65 years, resulting in an approximate 50% reduction from maximal capacity.2 These declines are a leading contributor to loss of independence and poor quality of life3 and predict disability,4 hospitalisation5 and death.6

Sarcopenia, characterised by low muscle mass, muscle weakness and impaired physical function,7 is prevalent in older individuals globally (10–27% in those aged 60 years and over)8 and affects around one in five Australians aged 60 years and over.9 It is categorised as primary (age related) or secondary when there are identifiable causal factors beyond age.7 Risk factors include physical inactivity, malnutrition and systemic disease,7 with a 2020 meta-analysis reporting a higher sarcopenia prevalence in dementia (26.4%), diabetes (31.1%) and respiratory disease (13.3%).10

Sarcopenia is linked to a myriad of adverse outcomes, including functional decline, falls, fractures, hospitalisation and increased risk of death,5,11,12 and considerable healthcare costs.13 It is also associated with an increased risk of frailty, influencing the progression from robustness to pre-frailty and frailty.14 Sarcopenia and frailty, although sharing clinical features, are distinct.15 Frailty is a multidimensional age-related syndrome, with declines in physical and cognitive reserves increasing vulnerability to adverse health outcomes.16 In contrast, sarcopenia is a skeletal muscle disease, considered a physical component of and precursor to frailty.17

Timely identification and intervention for sarcopenia are critical for improving patient outcomes, including maintaining mobility, independence and quality of life.7,18 Several operational definitions and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia exist,7,19–22 with the Australian and New Zealand Society for Sarcopenia and Frailty Research (ANZSSFR) endorsing the revised European Working Group for Sarcopenia in Older People’s (EWGSOP2) definition.7,23 EWGSOP2 recommends a case-finding approach using the five-item SARC-F (strength, assistance with walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs and falls) questionnaire or clinical suspicion. Grip strength or chair stand measures assess pre-sarcopenia, while dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) or bioelectrical impedance (BIA) detect low appendicular muscle mass and confirm sarcopenia. Severe sarcopenia is confirmed using physical performance measures like gait speed, the short physical performance battery (SPPB) test or the timed-up-and-go test (TUG).7 Following diagnosis, individuals should be offered resistance-based exercise,18,23 combined with a protein-rich diet or protein supplementation for those with inadequate intake.18,23 Emerging evidence suggests that nutritional interventions like creatine, beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB), vitamin D and multi-nutrient supplements might benefit muscle mass and/or strength in older adults with deficiencies and those with sarcopenia.24,25

Sarcopenia is often overlooked in clinical practice,7 with poor awareness of the importance of skeletal muscle to health and chronic disease prevention among healthcare professionals (HCPs) and the public.12,26–29 Barriers identified by HCPs in the literature include lack of diagnostic tools and treatment protocols, time constraints, and insufficient awareness and motivation.12 In July 2023, eight representatives (across three states: News South Wales, Victoria and South Australia) from Australia’s primary care and research communities (two general practitioners, two geriatricians, two practice nurses and two senior academics with a background in allied health) convened to address local barriers to implementing sarcopenia screening, assessment and management. Solutions were proposed to improve the implementation of muscle health assessment and management in general practice. The half-day, face-to-face meeting involved breakout sessions focusing on (1) prioritising muscle loss in general practice and identifying instances of muscle loss and (2) strategies for screening and monitoring muscle loss. The roundtable members then reconvened to discuss and reach consensus on key barriers and ideate solutions. This article summarises the main findings and discussions from the meeting.

Strategies for enhancing muscle health in general practice

Five key barriers to sarcopenia screening, assessment and management in primary care were identified:

- inadequate awareness regarding the implications of sarcopenia and its link to chronic disease among the public

- insufficient knowledge and training among HCPs in recognising and managing poor muscle health in older patients

- absence of tools, resources and clear protocols for assessing and managing muscle health in primary care

- time constraints and workforce shortages

- limitations in both patient access to services and specific funding for these services.

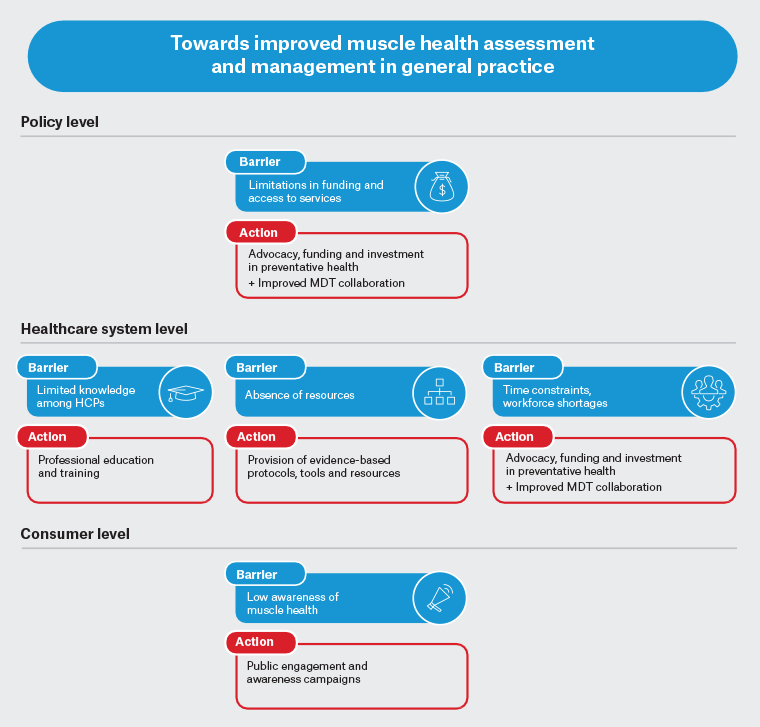

Strategies for implementing muscle health assessment and management involve five main themes: (1) public awareness, (2) professional education, (3) tools and resources, (4) advocacy and policy and (5) collaborative efforts (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Key barriers to sarcopenia screening, assessment and management in Australian primary care, along with proposed strategies to address them.

HCP, healthcare professional; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Theme 1: Improving public awareness and engagement

Despite sarcopenia’s clinical significance, public awareness is low,27 particularly compared to other age-related conditions like dementia and osteoporosis.28 Recent research by ANZSSFR, utilising a consumer Delphi process, found that consumers value outcomes related to sarcopenia, such as maintaining physical function and preventing falls, and most reported a willingness to undergo assessment and treatment.30 However, due to its onset with age, symptoms might be inadvertently overlooked by patients, attributed to normal ageing or viewed as less critical than widely understood health conditions, hindering early diagnosis and preventative strategies. Initiatives should prioritise public engagement, emphasising sarcopenia’s seriousness and adverse effects and the importance of maintaining muscle health into old age. It should also be emphasised that this condition is not an inevitable part of ageing; with early detection and intervention, proactive measures can be taken (and should be recommended early in mid-life) to prevent and slow its progression. A shift in perspective is needed, with sarcopenia no longer being categorised as a condition exclusive to older adults. A ‘life course approach’ should be adopted to prioritise building and preserving muscle mass through healthy behaviours formed early in life and maintained through adulthood to minimise impairment in older age.18–20

Theme 2: Professional education

To enable early detection, intervention and prevention of poor muscle health, education to promote awareness and adequate knowledge among HCPs, particularly general practitioners, is needed.31 Previous research highlighted limited awareness and knowledge among HCPs,12,26,29 with only 14.7% correctly identifying sarcopenia as a disease with limited knowledge about the diagnostic criteria.12 Despite sarcopenia being recognised formally as a disease since 2016 (2019 in Australia),32,33 muscle health is rarely considered in routine practice, and sarcopenia screening and diagnoses are uncommon.34,35 Continuing professional development (CPD) should be prioritised to educate current HCPs on the importance of muscle health and screening and diagnostic assessments.12 Importantly, CPD can help inform HCPs about recommended prevention and treatment strategies, including the latest evidence on the benefits of exercise (in particular resistance training), ensuring adequate energy and protein intake, and the use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS – powdered or ready-made drinks that provide calories, protein, vitamins and minerals) when nutritional intake is inadequate, as well as establishing referral pathways to relevant allied HCPs. The current GP curriculum limits the availability of professional education and training on sarcopenia.36 Thus, as a priority, there is a need for an improved curriculum within undergraduate medical/health programs that integrates key competencies, learning outcomes and case studies covering the clinical importance of muscle health and sarcopenia, including how to identify and treat this disease as well as highlighting the importance of prevention in mid-life.

Theme 3: Provision of tools and resources

Despite available screening and assessment tools for sarcopenia, the global lack of agreement and standardisation leads to varied diagnostic cut-offs and criteria.23 ANZSSFR recommends adopting the EWGSOP2 sarcopenia definition in Australia and New Zealand.23 Although no international consensus on the definition of sarcopenia exists, efforts to address this issue are under way by the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS).23,37 The eight experts also noted the lack of practical resources for primary care professionals when considering muscle health. Clearly defined evidence-based protocols, care pathways and primary care toolkits are needed. Furthermore, diagnostic tools must be validated, standardised, simple and affordable for easy adoption into routine practice. Integrating diagnosis into electronic medical record (EMR) software is recommended to streamline muscle health assessment and monitoring in primary care. Finally, the inclusion of sarcopenia screening, assessment and/or treatment/management as part of Medicare-funded items (eg Heart Health Checks, health assessments for people aged 45–49 years, health assessments for people aged 75 years and older, chronic disease GP Management Plans and Team Care Arrangements) will be critical to reduce the future health and economic burden of this disease as our population ages.

Theme 4: Advocacy and policy

The Australian nurse shortage was identified as another barrier to widespread monitoring of sarcopenia. Health Workforce Australia predicts a shortage of over 100,000 nurses by 2025.38 Adequate funding for primary healthcare is essential to support the nursing and allied health workforce, thereby improving patient access to services. A collaborative effort from government, universities and local health departments is necessary to address workforce shortages in primary care. Addressing workforce shortages and time constraints also requires improved work priority through advocacy, policy and HCP education. By raising awareness of the significance of sarcopenia, akin to osteoporosis and dementia, immediate attention can be directed to muscle health and leveraging existing healthcare resources. Furthermore, improving advocacy and policy for muscle health might help reduce the long-term demand for aged care services and promote a healthcare system that prioritises preventative health, with focused attention on pre-frailty and ageing in place.

Theme 5: Improved collaborative efforts

Due to the multifaceted nature of sarcopenia, a multidisciplinary, team-based approach in primary care is crucial for effective sarcopenia screening, assessment and management.39 Although GPs and practice nurses are well placed to screen for muscle health,40 there is a significant opportunity for other allied HCPs (eg exercise physiologists, dietitians, podiatrists, physiotherapists and community pharmacists) to actively participate to help facilitate earlier detection, provide a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s condition and assist in regular monitoring. Furthermore, with exercise and diet as recommended interventions for sarcopenia, exercise physiologists and dietitians could preferentially be referred to following diagnosis. Implementing a multidisciplinary, team-based approach to the screening, assessment and management of sarcopenia would require additional government funding to support initiatives such as the patient enrolment policy (MyMedicare) or the workforce incentive program (practice stream), which is designed to encourage multidisciplinary and team-based models of care.

Conclusion

Sarcopenia remains under-recognised in clinical practice, despite its serious consequences. Preserving muscle health is pivotal in preventing and managing chronic conditions in Australia’s ageing population and promoting healthy ageing, independence and quality of life. Urgent action is needed to raise awareness and address primary care challenges in sarcopenia screening, assessment and management. This article proposes solutions and emphasises the importance of collaboration among HCPs, patients, professional societies such as the ANZSSFR, universities, EMR software vendors and the government in addressing these challenges.

Key points

- Sarcopenia is a disease defined by low muscle mass, muscle weakness and impaired function that is associated with a myriad of adverse health outcomes.

- Raising awareness among HCPs and the public about the serious consequences of poor muscle health is critical for improving patient outcomes.

- The diagnosis and management of sarcopenia is often overlooked in clinical practice, necessitating urgent action to improve screening and management in primary care.

- There is a need for increased public awareness and professional education, adequate resources for HCPs and resolution of workforce shortages.

- Collaboration among HCPs, organisations and the government is crucial for addressing challenges in sarcopenia diagnosis and management.