Knee osteoarthritis is a prevalent and disabling condition that impacts activities of daily living, participation in work and family roles, and overall quality of life. With population growth and ageing, an increasing number of Australians are living with knee osteoarthritis (over 1.9 million people in 2019, representing 126% growth relative to 1990 numbers).1 National estimates indicate that knee osteoarthritis is associated with over 59 000 years lived with disability annually, exceeding the disability burden of dementia, stroke or ischaemic heart disease.1 Knee osteoarthritis also has a major economic impact in Australia, with over $3.5 billion spent annually on osteoarthritis-related hospital admissions2 and an estimated productivity loss of $424 billion.3 International clinical guidelines consistently recommend non-surgical modalities as the mainstay of knee osteoarthritis management, with referral for consideration of joint replacement surgery reserved for people with late-stage disease.4–6 Concerningly, low value care (care that is wasteful, ineffective and/or harmful) persists across the knee osteoarthritis journey. This is often fuelled by misconceptions about osteoarthritis, including inaccurate beliefs around diagnosis and management, that are amenable to change through education and effective communication.7

Why do we need a Clinical Care Standard for knee osteoarthritis?

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has developed a range of Clinical Care Standards. These aim to: (i) support the delivery of evidence-based clinical care for a health condition or procedure; (ii) reduce variation in clinical care across Australia; and (iii) promote shared decision making between health professionals and consumers. Unlike clinical guidelines, Clinical Care Standards do not describe all the components of care. Instead, they encompass a limited set of quality statements that describe the expected care for a health condition or procedure and highlight priorities for quality improvement.

Evidence of low value osteoarthritis care (specifically, high rates of knee arthroscopy among older Australians, with substantial geographic variation)8 pointed to the need for the first Clinical Care Standard targeting knee osteoarthritis. In 2017, the Osteoarthritis of the Knee Clinical Care Standard was launched following a comprehensive development process that involved topic experts and consumers, wider stakeholder consultation, and national peak body endorsement. Seven years on, we introduce the updated Osteoarthritis of the Knee Clinical Care Standard and indicator set (available at www.safetyandquality.gov.au/oak-ccs),9 which have been carefully revised to ensure alignment with new evidence, contemporary international guidelines, and advances in person-centred care. The updates also target current priorities for improving osteoarthritis care through reducing low value care. In addition to reducing inappropriate arthroscopy, these priorities include reducing unnecessary imaging, opioid prescribing, and unwarranted knee replacement where optimal non-surgical management has not been trialled.

What has changed?

An overview of the updated Osteoarthritis of the Knee Clinical Care Standard is presented in Box 1. While the scope and goals remain similar, there are several key changes and new features. Importantly, the quality statements are intended to apply to all medical practitioners, allied health professionals and nurses who provide knee osteoarthritis care, to promote consistency in assessment, management, and communication. The settings to which the Clinical Care Standard apply are now clearly articulated, with broad applicability to all settings where osteoarthritis care is delivered. These include community and primary healthcare services, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Organisations, hospital settings, and private medical clinics.

| Box 1. Overview of the updated Osteoarthritis of the Knee Clinical Care Standard9 |

| Scope and goals |

| The Osteoarthritis of the Knee Clinical Care Standard describes the care that people aged 45 years and over should receive when they present with knee pain and are suspected of having knee osteoarthritis. This Clinical Care Standard aims to improve timely assessment and optimal management for people with knee osteoarthritis. It spans early clinical assessment, diagnosis, ongoing non-surgical management, specialist referral and consideration of surgery, if required. It does not cover the management of knee pain due to other diagnoses or recent trauma, nor does it cover rehabilitation after joint replacement surgery for knee osteoarthritis. |

| |

| Quality statement 1: Comprehensive assessment and diagnosis |

| A patient with suspected knee osteoarthritis receives a comprehensive, person-centred assessment which includes a detailed history of the presenting symptoms, comorbidities, a physical examination, and a psychosocial evaluation of factors affecting quality of life and participation in activities. A diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis can be confidently made based on this assessment. |

| |

| Quality statement 2: Appropriate use of imaging |

| Imaging is not routinely used to diagnose knee osteoarthritis and is not offered to a patient with suspected knee osteoarthritis. When clinically warranted, x-ray is the first line imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and ultrasound are not appropriate investigations to diagnose knee osteoarthritis. The limited value of imaging is discussed with the patient, including that imaging results are not required for effective non-surgical management. |

| |

| Quality statement 3: Education and self-management |

| Information about knee osteoarthritis and treatment options is discussed with the patient. The patient participates in developing an individualised self-management plan that addresses their physical, functional, and psychosocial health needs. |

| |

| Quality statement 4: Physical activity and exercise |

| A patient with knee osteoarthritis is advised that being active can help manage knee pain and improve function. The patient is offered advice on physical activity and exercise that is tailored to their priorities and preferences. The patient is encouraged to set exercise and physical activity goals and is recommended services or programs to help them achieve their goals. |

| |

| Quality statement 5: Weight management and nutrition |

| A patient with knee osteoarthritis is advised of the impact of body weight on symptoms. The patient is offered support to manage their weight and optimise nutrition that is tailored to their priorities and preferences. The patient is encouraged to set weight management goals and is referred for any services required to help them achieve these goals. |

| |

| Quality statement 6: Medicines used to manage pain and mobility |

| A patient with knee osteoarthritis is offered medicines to manage their pain and mobility in accordance with the current version of Therapeutic Guidelines (or locally endorsed, evidence-based guidelines). A patient is not offered opioid analgesics for knee osteoarthritis because the risk of harm outweighs the benefits. |

| |

| Quality statement 7: Patient review |

| A patient with knee osteoarthritis receives planned clinical review at agreed intervals, and management is adjusted for any changing needs. A patient who has worsening symptoms and severe functional impairment that persists despite optimal non-surgical management, is referred for assessment by a non-general practitioner specialist or multidisciplinary service. |

| |

| Quality statement 8: Surgery |

| A patient with knee osteoarthritis who has severe functional impairment despite optimal non-surgical management is considered for timely joint replacement surgery or joint-conserving surgery. The patient receives comprehensive information about the procedure and potential outcomes to inform their decision. Arthroscopic procedures are not offered to treat uncomplicated knee osteoarthritis. |

There is now a stronger focus on clinical diagnosis and avoidance of unnecessary imaging, notably magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and ultrasound. There is a clear stance that in the limited circumstances where imaging is indicated (restricted to suspicion of alternative diagnoses, the presence of atypical features, rapid worsening of symptoms, or where surgery is being considered), erect x-rays are the preferred option. Guidance is provided to help patients understand why imaging may not be beneficial in their circumstances. Highlighting the importance of self-management support, the quality statement on exercise now includes recommendations for physical activity, and a new quality statement on weight management (rather than “weight loss”) and optimal nutrition is included. The updated Clinical Care Standard also places greater emphasis on avoiding opioid analgesics for knee osteoarthritis, given the unfavourable risk–benefit ratio and the secondary role of medicines in ongoing osteoarthritis management.

New features to support cultural safety, equity and effective communication

Cultural safety and equity considerations have been incorporated throughout the updated Clinical Care Standard, to support care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with knee osteoarthritis. It is recognised that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience a higher burden of osteoarthritis and lower access to care than non-Indigenous Australians.10 To improve equitable access to care, overarching recommendations are provided for embedding cultural safety in health care, with links to relevant frameworks and resources. Specific cultural safety and equity recommendations are also linked to individual quality statements. These include collaborating with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, health practitioners and community services within a multidisciplinary care approach, and optimising care delivery through developing strong, trusting relationships and effective communication with patients and their families.

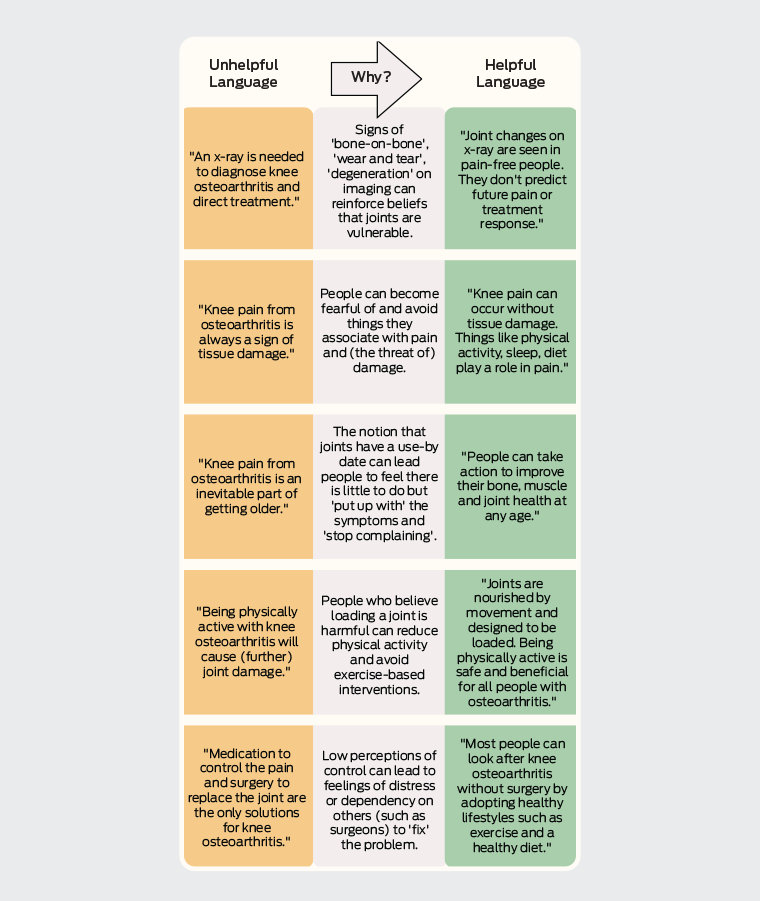

Poor clinician–patient communication contributes to low value care. For example, Choosing Wisely surveys involving Australian general practitioners, specialists and other health professionals found up to 73% were willing to request an unnecessary test, treatment or procedure if it aligned with patient expectations.11 A range of common patient misconceptions about osteoarthritis still exist,12 including perceptions that a scan is needed to diagnose knee osteoarthritis and direct treatment, and that being physically active with knee osteoarthritis will cause (further) joint damage. Despite efforts to move away from joint-centric language focusing on structural damage,13 a recent survey of Australian patients showed that outdated, negative terms (such as “wear and tear” and “bone on bone”) were commonly used by their healthcare professional to describe osteoarthritis.14 Such language can reduce engagement with effective care, such as exercise therapy.12 To support the delivery of evidence-based care, recommendations for effectively communicating with patients about their knee osteoarthritis are linked to each quality statement in the updated Clinical Care Standard. These recommendations include examples of positively framed language that practitioners can use to promote helpful beliefs and behaviours (Box 2).

Box 2. Unhelpful and helpful language tips for clinicians. Click here to enlarge

Resources to support consumers, clinicians and health services

Access to high-quality information about knee osteoarthritis can empower consumers and their families to be more involved in care decisions and promote treatment adherence and engagement in active self-management, to improve health outcomes.15 For each quality statement, links are provided to evidence-based consumer resources in a range of formats to meet diverse needs and preferences. These include interactive online activities and programs, and community activities and information resources for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Translational resources to accompany the Clinical Care Standard (for example, a consumer guide and fact sheets for clinicians and healthcare services) are also available online.9

Indicator set

To support local quality improvement activities, a revised set of pragmatic indicators accompanies the updated Clinical Care Standard.9 Indicators are provided for comprehensive assessment and diagnosis, appropriate use of imaging, education and self-management, medicines used to manage pain and mobility, patient review, and surgery. For example, specific indicators consider the proportion of patients who are diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis without the use of imaging, and the proportion of patients with knee osteoarthritis whose individualised self-management plan includes documented advice on physical activity. While no benchmarks are given, the indicators are designed to help healthcare services and clinicians evaluate how well they are implementing the care recommended in the Clinical Care Standard as part of quality improvement activities.

Conclusion

The updated Osteoarthritis of the Knee Clinical Care Standard is an important tool that can support best practice care for people presenting with suspected knee osteoarthritis. Emphasising the role of clinical diagnosis and with an enhanced focus on physical activity, exercise, weight management and nutrition, the Clinical Care Standard covers the full spectrum of care that should be trialled before consideration of surgery. The addition of cultural safety and equity considerations and clinician communication tips, together with new guides for healthcare services, clinicians and consumers, ensures a contemporary resource with practical value.