Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults have a higher prevalence of chronic respiratory conditions compared with the overall Australian population.1 The high prevalence of disease is underpinned by a history of colonisation and racism, the effects of which continue today alongside intergenerational trauma and disadvantage.2 Coupled with the difficulties of overlapping conditions complicating diagnosis are difficulties in accessing specialist care and challenges associated with a transient primary healthcare workforce in remote communities. In the Northern Territory (NT), over 30% of the population self-identifies as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, with most of these people living in remote areas.3 Due to impaired access to specialist respiratory healthcare and workforce shortages in remote and rural Aboriginal communities, this paper, based on our experiences in the NT,4–7 aims to provide a brief guide on the approach to chronic respiratory disorders that might be of use for primary care nurses, Aboriginal health practitioners and medical practitioners working in rural/remote Australia.

History and examination

Demographics and history

In primary care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults with chronic respiratory disorders typically present at ages 40–60 years,4 with a marginally higher female representation (57%) and a higher prevalence in remote compared with urban areas.5 Shortness of breath is one of the most common presenting symptoms (in approximately 62% of patients), followed by productive cough (30%), which is more commonly reported among patients with underlying bronchiectasis8–10 (refer to Table 1 for a comparison of history and examination findings). In addition, details of past respiratory medical history, hospitalisations, family history and other relevant medical comorbidities, including smoking and cannabis/vaping use, should be considered. The annual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health check (Medicare Benefits Schedule Item 715) is an appropriate opportunity for these screening questions to be asked.

| Table 1. Clinical features and management of chronic respiratory conditions in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people |

| |

COPD |

Bronchiectasis |

Bronchiectasis/COPD |

Asthma |

Asthma/COPD |

| Clinical parameters |

| Smoking history |

++++ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

+++ |

| Cough |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

| Sputum production |

++ |

++++ |

+++ |

+ |

++ |

| Wheezing |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+++ |

++ |

| Shortness of breath |

+++ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

++ |

| Chest auscultation |

Reduced breath sounds |

Crackles |

Reduced breath sounds and crackles |

Rhonchi |

Reduced breath sounds and rhonchi |

| Radiology |

Emphysema/airway inflammation |

Bronchiectasis changes |

Emphysema and bronchiectasis changes |

Normal or airway inflammation |

Airway inflammation/emphysema |

| Spirometry |

Obstructive pattern |

Restrictive pattern |

Obstructive and restrictive pattern |

Normal or obstructive or restrictive pattern, with bronchodilator response |

Obstructive or restrictive pattern, with bronchodilator response |

| Medications |

| SABA/SAMAA |

+ |

>+ |

+ |

+++ |

>++ |

| LABA/LAMAA |

++ |

+ |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

| ICSA |

+ |

CautionB |

CautionB |

+++ |

++ |

Note: this is a general guideline only. Individual patients’ scenarios and clinical judgment should be taken into consideration in clinical decision making.

ACould be considered.

BCaution: extreme caution has to be exercised in using inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).

++++, extremely likely; +++, more likely; ++, likely; +, less likely; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LABA, long-acting β2 agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists; SABA, short-acting β2 agonists; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonists. |

Physical examination findings

There is a paucity of literature describing common respiratory examination findings in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Reduced breath sounds on auscultation might be related to poor respiratory efforts without underlying respiratory conditions or might indicate the presence of COPD. Reduced breath sounds along with crepitation or crackles might be suggestive of associated bronchiectasis.11 Chest auscultation findings of rhonchi/wheezing might indicate the presence of asthma or might also indicate the presence of chronic bronchitis, bronchiolitis, small airway disease or asthma/COPD overlap.12,13 Findings of squeaks might suggest hypersensitive pneumonitis, small airway disease or bronchiolitis.14 Further, collecting vital signs and other relevant physical examination details is critical.15 Finger clubbing might also be observed (Figure 1). The causes of clubbing in other ethnic populations are typically well established and/or multifactorial.16 However, among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, conditions that could be responsible for clubbing are not well described in the existing literature.

Figure 1. Finger clubbing in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish the photograph.

Investigations

Lung function tests

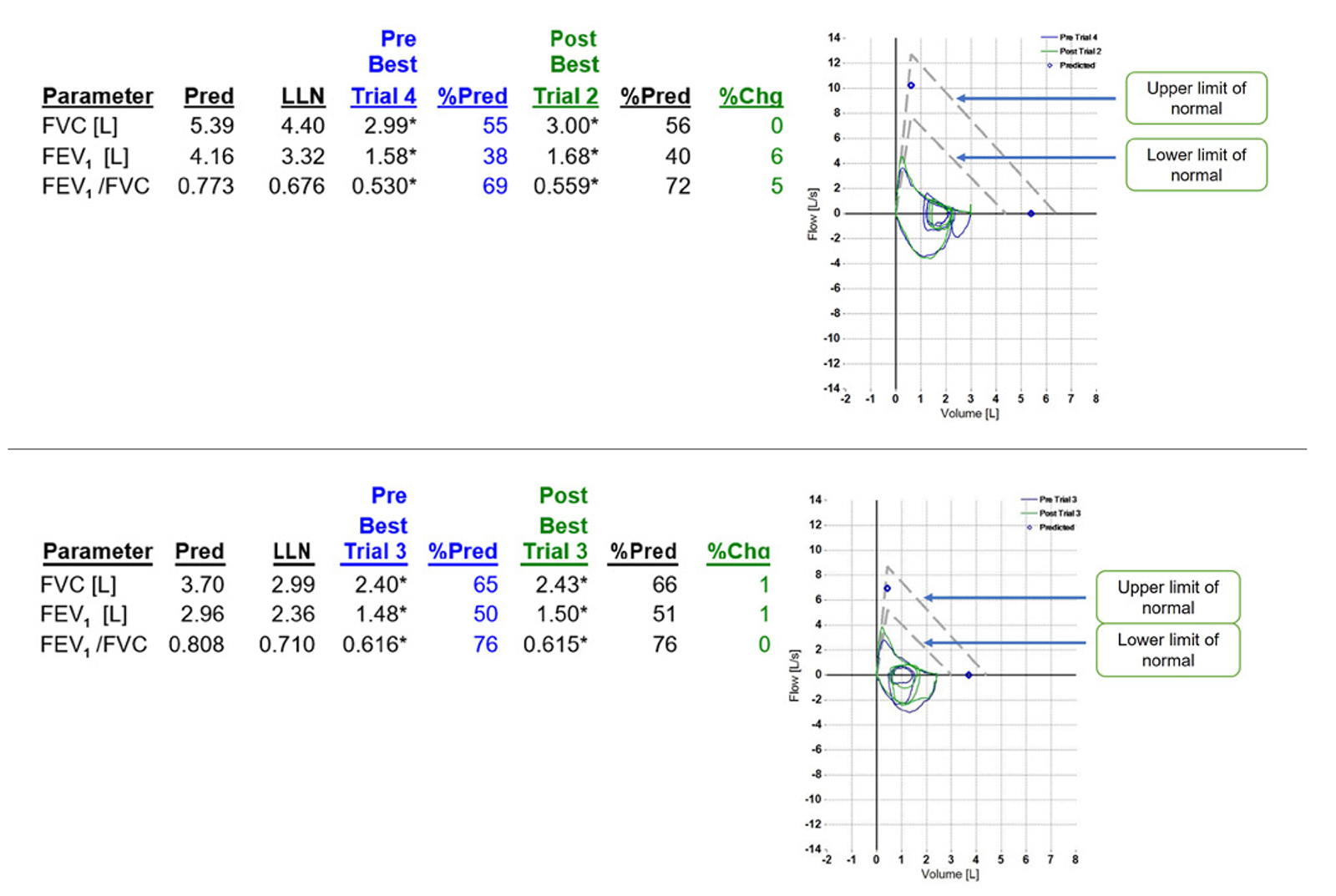

To date, spirometry reference norms have not been well established for older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults.17 There is ongoing controversy regarding the need and utility of ethnicity-specific references for spirometry. The differences seen in spirometry between ethnicities are more likely due to social constructs resulting in early life disadvantage, such as prematurity, passive smoking and/or ongoing early lower respiratory infections.18,19 Nonetheless, spirometry is a useful tool and plays an integral role in diagnosis, assessment of disease severity and in monitoring and guiding therapeutic interventions. A recently published study applied non-Indigenous references for spirometry and showed that only 10–12% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients displayed normal-range spirometry parameters for forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC).20 In contrast, the FEV1/FVC percentage predicted values tended to be within the normal range (95–97%).20 Restrictive or mixed ventilatory impairment is the most common spirometry pattern observed among many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, including patients with bronchiectasis (Figure 2). However, an obstructive pattern could be observed among patients with predominant COPD.20 Bronchodilator response could be observed in up to 17% of patients.12 Concurrent respiratory comorbidities are common among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients presenting with respiratory symptoms, and therefore spirometry might be non-specific, and mixed impairments must be considered in the context of multiple symptoms.12,20,21

The lack of normative values for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults is especially important when using spirometry severity grades to guide pharmacotherapy (eg in using the Australian COPD concise guidelines [COPD-X]).22 Moreover, it is critical to acknowledge that the COPD-X guidelines have not been extensively validated in the wider Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. When using non-Indigenous reference norms, the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with COPD undergoing spirometry testing can be classified as having severe or very severe airflow obstruction.23 Therefore, by adopting the COPD-X guidelines, most patients are likely to be prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), which might not be appropriate in certain circumstances, such as in the case of concurrent bronchiectasis.24 Given the lack of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific spirometry reference values, the FEV1/FVC ratio might be a better parameter to assess airway impairment alongside culturally specific assessment of impacts on quality of daily life.24 Furthermore, patient understanding and cooperation are extremely important to accurately assess spirometry.25 A previous study among rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander residents demonstrated that only 42% of lung function tests were acceptable for session quality.26 Adequate support and resourcing for primary care clinicians to conduct routine spirometry might be difficult. Resources such as the Indigenous Spirometry Training Workshops can be useful for clinicians upskilling in remote clinics.

Figure 2. Examples of typical lung function patterns in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with mixed restrictive and obstructive findings. %Chg, percent change post bronchodilator; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; Flow [L/S], litres per second; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal; Pre, pre-bronchodilator; Post, post-bronchodilator; Pred, predicted.

Chest radiology

Chest radiology is integral to the diagnosis and management of several respiratory conditions, with chest computed tomography (CT) being increasingly used for this purpose. However, chest CT is not easily accessible in remote communities. In these circumstances, a chest X-ray (CXR) might be a reasonable alternative option. Assessed against the gold standard of a CT scan, the combination of CXR and spirometry has shown a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 72% in diagnosing airway disease in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, compared with a sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 77% when using spirometry alone.21 Nonetheless, a recent study on chest CT scans confirmed that complex and concurrent chest radiological abnormalities are highly prevalent among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respiratory patients,27 such as advanced emphysema, bronchiectasis and cystic lung disease.28 When feasible and available, yearly CXR might be helpful in chronic lung disease to monitor progress and for the early diagnosis of any new lung conditions, such as malignancy. However, if patients have a clinically judged need for a chest CT, it should be facilitated. The implications and feasibility of the proposed rollout of a lung cancer screening program among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in remote communities are yet to be determined.29 Currently, the presence of non-malignant lung nodules and lymphadenopathy are frequent chest CT findings in this population.30,31

Sputum microbiology

Sputum microbiology data are limited among the adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, including among patients with bronchiectasis. Common organisms cultured among patients with chronic respiratory disease include Haemophilus influenzae (47%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (26%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (22%) and Moraxella catarrhalis (17%).8,10,32 Sampling of sputum should be considered during exacerbation of airway disease, if appropriate, to guide antimicrobial therapy. More specifically, testing for acid-fast bacilli should be considered if there is clinical suspicion of tuberculosis.33 However, there might be constraints in collecting and processing sputum samples in certain remote clinics. Hence, local guidelines and recommendations on sputum sampling need to be considered.

Clinical features and management of specific conditions

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COPD is highly prevalent among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, with a reported prevalence of up to 49%.4 Shortness of breath on exercise is the most common presenting symptom among patients with COPD.8 Although tobacco smoking is one of the most important risk factors for the development of COPD, cannabis use and exposure to environmental smoke, such as bushfires, or passive smoking in the context of overcrowding might also contribute to exacerbation of airway disease.8,34,35 Patients with COPD also tend towards overall lower body weight and body mass index,20 which indicates a higher disease burden due to higher resting energy expenditure and higher basal metabolic rate.36 There are significant differences in the clinical manifestations of COPD between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and non-Indigenous patients.37 Concurrent bronchiectasis among patients with COPD is highly prevalent (up to 50%).8,10 FEV1 values on spirometry in patients with COPD are significantly reduced compared with predicted values (46% predicted)20 and, in line with chest radiology, demonstrate advanced COPD disease burden, including the presence of bullous disease.28 Exacerbation of airway disease, including COPD, is a common reason for hospital admission.38

Currently, evidence on pharmacotherapy interventions and guidelines for COPD management specific for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients is lacking. However, airway-directed inhaled pharmacotherapy, such as short-acting β2 agonists, short-acting muscarinic antagonists, long-acting β2 agonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonists and ICS, are widely used in the management of COPD.24 Studies examining non-pharmacotherapy COPD management (eg pulmonary rehabilitation) have reported that these interventions are difficult to access, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in remote communities.39 Hypoxaemia and oxygen desaturation on exercise are not uncommon in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with COPD; however, there are barriers in facilitating home oxygen therapy, often stemming from household crowding and exposure to smoke in remote communities.40 Furthermore, patients living in remote communities could have difficulties accessing, maintaining and supplying constant power to oxygen equipment. Despite the challenges associated with home oxygen, previous studies have demonstrated benefits and outcomes in this population.41 Therefore, home oxygen therapy should be considered and facilitated when appropriate and feasible. Social and education programs regarding smoking cessation (including cannabis) supported by general practitioners, Aboriginal health practitioners and/or nurses might not only improve the patient’s symptom burden and help prevent lung disease, but also make a home environment where oxygen therapy is more safe/feasible.42 Moreover, improved education and communication regarding the disease itself will aid in improving patient’s self-management and prevent hospitalisations.9

Bronchiectasis

Chronic respiratory tract infections play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology among patients with bronchiectasis, thereby giving rise to a vicious cycle of recurrent infections and airway inflammation.7 There is growing evidence in the literature to suggest that bronchiectasis is highly prevalent among adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.6,32,43–45 Furthermore, concurrent presence of other medical comorbidities, including COPD, cardiovascular and chronic kidney diseases, appears to be driving higher overall mortality.6,32 Lung function parameters more often display a restrictive pattern among patients with bronchiectasis in isolation and demonstrate much more severe and mixed impairment when COPD co-exists.10,20

Although COPD and bronchiectasis share several similar clinical features, the management of these conditions differs; hence, in clinical practice, differentiating these conditions and recognising concurrent COPD and bronchiectasis, especially when inhaled directed airway pharmacotherapy is considered, is vital. It is generally recommended that ICS are used with caution in patients with bronchiectasis. Importantly, the use of ICS among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults with bronchiectasis could contribute to yearly decline in FEV1.46 The exact reason for excessive decline with ICS use is unknown, but it is possible that ICS perpetrates ongoing airway inflammation by facilitating higher bacterial burden. Hence, extreme caution has to be exercised when using ICS in this population with bronchiectasis until further research is available to demonstrate safety and efficacy.

Sputum clearance manoeuvres are recommended as one of the main treatment modalities for patients with bronchiectasis.47 Airway clearance interventions are less frequently implemented among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients diagnosed with bronchiectasis,32,39 and more needs to be done to address access barriers to chest physiotherapy programs for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.48 These interventions might reduce recurrent presentations of exacerbations, the use of antibiotics and hospital admissions. Online resources such as the Bronchiectasis Toolbox can be of use for patient education and management.49 In the future, exploring the feasibility and efficacy of telehealth models for specialist or allied health interventions might be particularly useful among populations residing in remote areas.

Asthma

The prevalence of asthma among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians is generally reported to be between 7% and 26%.4 The hallmark symptoms of asthma, including cough, wheezing, chest tightness and shortness of breath, are very similar to those of COPD and bronchiectasis, which are also highly prevalent in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, alongside a high prevalence of smoking, and might mimic asthma.4,7,32 Furthermore, environmental influences, such as exposure to bushfire smoke in the vicinity of remote communities can have an influence on chronic airway diseases (Figure 3).35 Clinical features such as cough, wheeze, chest tightness, variable shortness of breath and the presence of bronchodilator response on spirometry are indicative of asthma.12 However, a study from the Top End Health Service demonstrated that almost half of those with a bronchodilator response had radiological evidence of COPD and/or bronchiectasis, and thus this finding must be interpreted with caution.12 Asthma diagnosis and management guidelines specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people might be useful in the future, including the feasibility, safety and efficacy of biological drugs.

Figure 3. Bushfire smoke during the dry season in the Northern Territory. Bushfire smoke in the vicinity of remote communities can have adverse effects on the health of those with chronic airway diseases.

Respiratory and concomitant medical comorbidities

Concomitant medical comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes and chronic kidney disease, are present in 13–46% of people with chronic respiratory disorders.8,10,32,50 Obstructive sleep apnoea is also highly prevalent in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults.51 The concurrent presence of comorbidities might give rise to higher overall morbidity and mortality. Hence, it is imperative that addressing and managing comorbidities should be considered in the holistic management of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with respiratory disorders. The annual health check provides an ideal opportunity for early prevention and screening, as well as tracking the progress of any respiratory disorders.15 Chronic disease management plans and team care arrangements are also critically important for optimising respiratory and overall health. For example, chronic disease plans are an opportunity to address immunisations for pneumococcal disease, influenza, COVID-19 and pertussis if required; the team care arrangement provides opportunities to refer to physiotherapy and other specialised services.

Conclusion

There is overwhelming evidence that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians exhibit different clinical and physiological manifestations of chronic respiratory conditions. Due to a gap in guidelines specific for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, clinicians are reliant on general population guidelines. It is critical to understand the different demographic and clinical manifestations, including lung function parameters and the presence of respiratory comorbidities, to optimise management for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic respiratory conditions. Furthermore, collaborative and constructive efforts between primary care services, remote community organisations and specialist services would aid in tackling the chronic health burden among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults.

Key points

- COPD in isolation or concurrent with bronchiectasis is highly prevalent.

- In the presence of multirespiratory morbidity, symptoms might mimic asthma.

- Restrictive impairment is the most common spirometry pattern.

- General population guidelines might not directly apply to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

- Consider caution in the use of ICS in patients with combined COPD and bronchiectasis.

Note/disclaimer

The content represented/recommendations in this paper are based on the authors’ clinical/research experience in the treatment/management of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with respiratory disorders in the Top End region of the NT. Although the clinical discussion presented is likely relevant to other remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities outside of this region, the authors acknowledge that not all aspects are generalisable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations within the NT or across Australia. As such, other intrinsic or extrinsic factors need to be considered, including household overcrowding, indoor air pollution, recurrent respiratory infections and other social or geographic determinants that might have an influence on respiratory disorders. Hence, health workers are urged to take into account individual patients’ clinical scenarios and sociodemographic characteristics in clinical decision making. Further, an individual’s ethnicity might not have any influence on the presence or absence, or the severity, of lung diseases.