Head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, with 890,000 new cases in 2018.1 The incidence of HNSCC is expected to increase by 30% to 1.08 million new cases annually by 2030.1 Within Australia, head and neck cancer is the seventh most common cancer diagnosed.2 As the incidence of head and neck squamous cell cancer continues to rise, along with advances in head and neck cancer treatments, general practitioners (GPs) will be faced with an influx of head and neck cancer survivors and play a pivotal role in their long-term care. Figure 1 provides a general overview of the classification and subtypes of HNSCC.

Current clinical practice defines the Australian head and neck oncology framework as a five-year follow-up period by surgical and oncological specialists following treatment. If there is no recurrence of malignancy or other acute clinical concern during this time, the patient is subsequently discharged into the care of their GP.3

Reaching the five-year mark is indeed a significant milestone. However, the ongoing care of head and neck cancer survivors can be complex and challenging. This involves managing chronic symptoms, many of which tend to worsen over time, as well as addressing the persistent risk of second primary malignancies, which accumulates over the patient’s lifetime.4–6

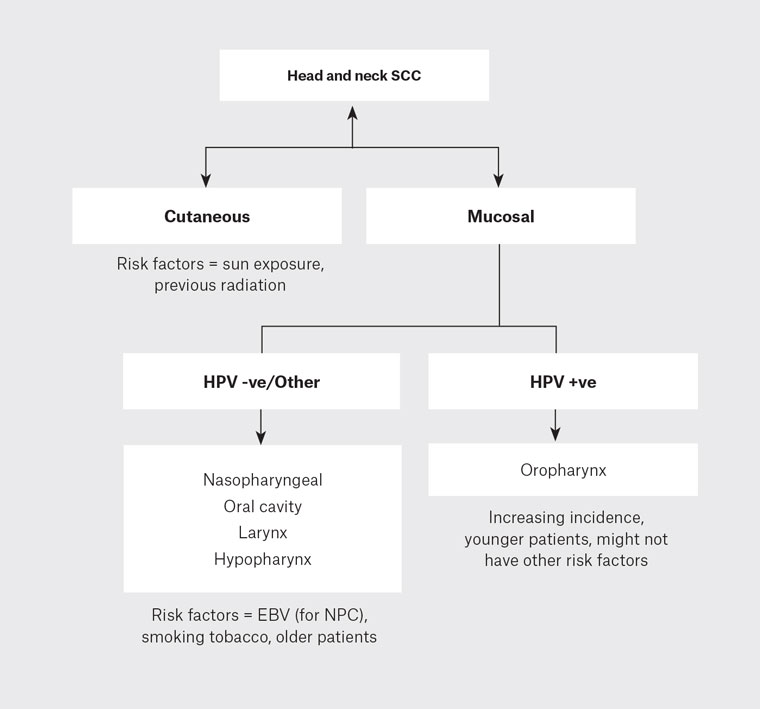

Figure 1. Head and neck cancer overview.

–ve, negative; +ve, positive; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Aim

This article aims to provide a practical evidence-based guide and comprehensive overview for GPs to follow for the surveillance and management of the head and neck cancer survivor.

What are the aims of a head and neck cancer consultation?

The main aims of a head and neck cancer consultation are:

- risk stratification and counselling (eg smoking and alcohol cessation)

- to detect and/or exclude recurrence

- to detect and/or exclude second primary malignancy

- management of chronic symptoms

- psychosocial support

- management of comorbidities.

Following a patient’s discharge from tertiary care, we recommend an annual clinic appointment dedicated to their head and neck cancer surveillance with GP specialists to follow up on any functional sequelae from treatment and to exclude recurrent or second malignancies. Box 1 illustrates the ‘red flag’ signs and symptoms that might indicate recurrent malignancy.

Emphasis on the multidisciplinary model will ensure holistic care of the HNSCC patient, as outlined in recent survivorship guidelines.7 Examples of this include referral to community speech pathology for the management of dysphagia, referral to psychology for psychological support and referral to physiotherapy for lymphoedema massage, all useful approaches to ensure a holistic approach for management of the head and neck cancer patient. Refer to Box 2 for a summary on HNSCC surveillance management within a consultation.

| Box 1. Clinical red flags and when to investigate further |

- NEW onset or worsening upper aerodigestive tract symptomatology

- Odynophagia

- Dysphagia

- Dysphonia

- Lateralising symptoms (ie unilateral sore throat, unilateral odynophagia)

- Otalgia with no clear cause

- Neck lump

- Haemoptysis

- Unexplained weight loss

- New cough, shortness of breath or noisy breathing

- Patient concern

|

| Box 2. Summary of head and neck squamous cell cancer management in primary care |

- Annual consultation dedicated to the patient’s head and neck squamous cell cancer surveillance

- History

- Examination: Palpation of the neck and examination of the oral cavity/oropharynx and any other relevant sites

- Multidisciplinary approach, including review by speech pathologists, dietitians, psychology and lymphoedema physiotherapy

- If the patient had a cutaneous head and neck cancer, then 6- to 12-monthly full-body skin checks by a skin specialist general practitioner or dermatologist is indicated

- Annual low-dose computed tomography of the chest for high-risk patients

- Persistent smokers and moderate–severe emphysema

- Recent ex-smokers with a long pack-year history (National Lung Screening Trial criteria)33

|

Risk stratification and counselling

Risk stratifying and effective counselling have vital roles within head and neck cancer surveillance. Smoking and alcohol are the leading risk factors for head and neck cancer (in particular those not caused by human papillomavirus [HPV]), and patients who continue to partake are at exceptionally high risk of developing recurrence or a second primary malignancy.8 Cessation of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption is of vital importance and has been shown to reduce head and neck cancer patients’ risk of further cancer.9

In recent years, the evolving paradigm surrounding HPV-related disease has caused a seismic shift in the risk stratification and clinical management of a specific subset of head and neck cancer patients. HPV now has a well-established role in the development of HNSCC, in particular oropharyngeal cancers, with distinct molecular, clinical and epidemiological characteristics compared with HPV-negative cancer patients.10 The rising incidence of oropharyngeal SCC, paradoxically occurring alongside declining smoking rates, can be fundamentally attributed to this ‘epidemic’ of HPV infection.11

Because HPV-positive HNSCC patients are typically younger without the traditional risk factors of smoking and alcohol, awareness and counselling for this cohort are especially important. HPV-related counselling that includes the prevalence and transmission of HPV infection (including risk to current or future partners after treatment and the role of vaccination) is recommended best practice in the European Head and Neck Cancer Society guidelines.12

HPV vaccination (Gardasil 9) has been approved since 2020 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of oropharyngeal HPV-related cancers (including HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58).13 Within Australia, the national vaccination program recommends a single dose of HPV vaccine for all younger people from age nine years.14

It should be noted that HPV vaccination can have a prophylactic role in preventing new HPV disease but does not treat pre-existing infection.

Ultimately, raising awareness, HPV-related counselling and vaccine advocacy will allow for the empowerment and holistic care of HPV-related HNSCC survivors.

What are the chronic symptoms to expect and how do we manage these?

Most head and neck cancer survivors will have long-term upper aerodigestive tract symptomatology secondary to their cancer treatment (surgery and/or radiation).

Common symptomatology includes chronic dysphagia, xerostomia, neck lymphoedema, conditions related to reduced mucociliary clearance after radiation (middle ear effusion, rhinitis or chronic rhinosinusitis) and depression/anxiety.

Chronic dysphagia

Indications to investigate further include worsening dysphagia, modification of diet and weight loss. Barium (contrast) swallow can be helpful in assessing the passage of contrast from the oral cavity to the stomach. A barium swallow can help differentiate between general dysmotility (ie secondary to presbyoesophagus) from obstructive causes that might be reversible, such as cricopharyngeal spasm or bar, oesophageal stenosis/stricture or pharyngeal pouches. Ensure patients are linked in with community speech pathologists. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy might also be indicated to exclude malignancy or to treat the condition (eg dilatation of radiotherapy-induced stenosis).

Xerostomia

A dry, sore mouth and throat is a common side effect in patients who have received primary radiation to their head and neck cancer. This might also be associated with the presence of dental caries or decay because prolonged hyposalivation can lead to disruption of the oral microflora.15–18 Therefore, encouraging good oral hygiene, as well modifying the diet to avoid dry, spicy or astringent foods, might help improve a patient’s symptoms. Artificial saliva products are also effective at alleviating symptoms.19 Using cholinergic agonists when residual secretory capacity is still present might also be beneficial.20

Neck lymphoedema

It is common for patients to have chronic neck lymphoedema if they have had treatment to their cervical lymph nodes through either radiotherapy and/or neck dissections. Chronically over time, this will feel fibrotic and is commonly described as ‘woody’. In severe cases, this can give rise to neck stiffness and a reduction in neck mobility. Physiotherapy with lymphoedema massage is useful in alleviating symptoms.

Depression/anxiety

Head and neck cancer is a debilitating physical and mental health disease with a significant impact on quality of life and subsequently on psychosocial outcomes. Head and neck cancer patients experience more psychosocial distress and have higher levels of depression and anxiety than other cancer populations.21–23 Head and neck cancer patients are found to have an increased risk of depression with suicidal ideation.24 Patients are linked in with cancer care psychosocial support services from the day of diagnosis; however, due to patient or systemic circumstances, many are lost to care. Therefore, continuity of psychosocial care within the community with foundational support from their GP specialist is paramount for the mental health and wellbeing of these survivors.

Ultimately, offering psychosocial support and early referral to services, including psychology and/or psychiatry for consideration of cognitive behavioural therapy and antidepressants, are important considerations within the head and neck cancer surveillance appointment.

Other (cardiovascular and respiratory health)

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of non-cancer morbidity and mortality among HNSCC survivors, with the average HNSCC patient having a three-fold greater likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease compared to their counterpart in the general population.25 This is largely attributed to their increased use of tobacco smoking and alcohol, which are known risk factors for the development of their primary cancer. HNSCC survivors also face an increased risk of death from any cause.26 Due to a prolonged smoking history, many have emphysema, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypothyroidism (particularly in the setting of patients after radiation therapy) and chronic kidney disease (secondary to nephrotoxicity from chemotherapeutic agents). Monitoring for these comorbidities, preventative care and counselling for lifestyle modifications can improve the morbidity and mortality rates for this high-risk cohort.

Visual atlas for clinical lesions of concern

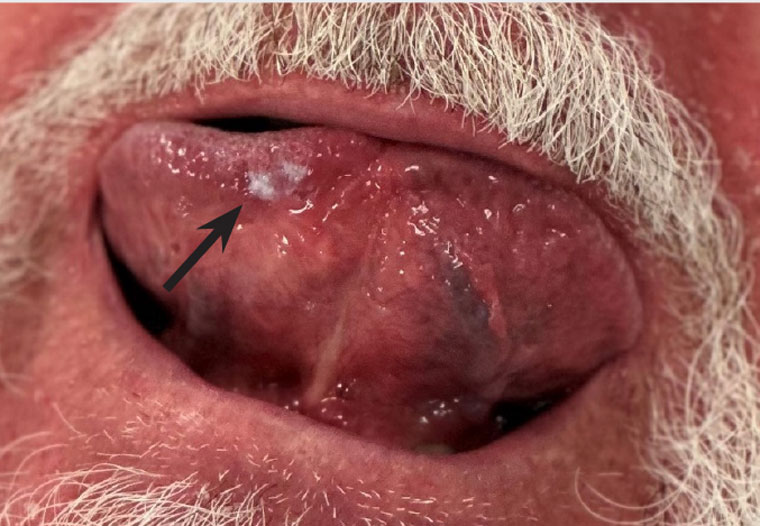

Figures 2 and 3 are images of commonly seen pre-neoplastic lesions within the oral cavity.

Which investigations?

An ultrasound of the neck is a practical starting point for any concerns in the neck: it is relatively cost-effective and does not expose the patient to radiation. If any suspicious nodes are identified, they can be followed up with a fine needle aspiration or core biopsy. These investigations should ideally be directed towards palpable lesions.

Barium swallow is a useful diagnostic tool for initial assessment of dysphagia and can exclude pouches, obstructive masses, strictures/stenosis and dysmotility issues.

Computed tomography with contrast is a useful investigation when cross-sectional imaging is required to investigate any concerning upper aerodigestive tract symptoms.

Magnetic resonance imaging can be considered, particularly for patients with cancers of the tongue or tongue base (suprahyoid pathology) or if there are any concerns for perineural spread. Magnetic resonance imaging provides excellent soft tissue definition.

Figure 2. Leukoplakia right ventral tongue (biopsy: mild dysplasia).

Leukoplakia is a clinical diagnosis and presents as a white patch (arrow) within the head and neck squamous cell cancer mucosa. Unlike fungal infections, leukoplakia usually cannot be wiped off. Management options include a short period of observation or biopsy.

Figure 3. Erythroplakia on left floor of mouth (white arrow, biopsy: invasive T1 squamous cell carcinoma). Note the erythematous lesion which had an underlying firm lesion to palpation. Leukoplakia on right floor of mouth (black arrow, biopsy: low grade dysplasia). Note the white plaque-like lesions on the right floor of the mouth.

Erythroplakia presents as a red patch in the mucosa and has a 44.9% rate of developing into invasive carcinoma.27 Features that might alert the clinician that this is a ‘suspicious’ lesion include the deeper erythematous patch, which is often well demarcated. It may or may not be surrounded with a white patch (erythroleukoplakia vs erythroplakia). Visual inspection should always be coupled with a physical examination (by palpation of the lesion), where it might feel irregular (particularly if an invasive cancer is present); however, it can also be soft to palpation at times. Management options include referral to a specialist for biopsy.

Screening for a second primary malignancy

A second primary malignancy contributes to a 23% mortality rate in head and neck cancer survivors.26 The lung is the most common location for developing a second primary malignancy in HNSCC survivors.5 Following diagnosis of a second lung malignancy, survival is exceptionally poor.28–30

Updated guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that patients with head and neck cancer with a 20 pack-year or more smoking history undertake annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT).31

The National Lung Cancer Screening Trial demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality by screening high-risk individuals using LDCT compared with radiography.32

There are currently no blood tests indicated for surveillance of head and neck cancer. However, in the future, liquid biopsy might play an increasing role in this area.

When to refer back to the oncologist or surgeon?

A referral back to the oncologist or surgeon should be made in the case of:

- patient concern – generally, HNSCC patients who have attended their surveillance appointments at hospital for five years are in tune with their own health/symptoms. If the patient is ever concerned about a new finding or symptom, this alone might be enough to warrant a referral back to the specialist

- clinical (red flags) or radiological suspicion.

Referrals with clinical concern will be categorised as an urgent appointment to be seen within 30 days. If there is histopathological evidence of recurrent malignancy, please consider telephoning the specialist on call directly to flag the referral so the patient’s appointment can be expedited.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the management and surveillance of head and neck cancer survivors represent a critical aspect of these patients’ ongoing care. As the incidence of HNSCC continues to rise globally, it is essential for healthcare providers, especially GPs, to be well equipped to face the challenges and responsibilities associated with surveillance past the five-year mark. Through a structured annual surveillance appointment, the key elements to the long-term care for the head and neck cancer survivor include risk stratification, counselling for lifestyle changes, detecting recurrence/second primary malignancies, managing chronic symptoms and providing essential psychosocial support. A multidisciplinary approach, close attention to red flag symptoms and collaboration with specialists when necessary are crucial to providing holistic and comprehensive care for the head and neck cancer survivor.

Key points

- Contact the ear nose and throat specialist or registrar on call, or submit an urgent referral, if ever there is any concern.

- Take patient concern seriously.

- Look out for red flag symptoms (new onset odynophagia, dysphagia, haemoptysis, dysphonia, lateralising symptoms, otalgia without a clear case, neck lump).

- Cross-sectional imaging is useful as an initial investigation, keeping in mind a negative computed tomography scan does not exclude malignancy (small mucosal cancers can be radiologically occult).

- For patients with a primary or presumed cutaneous skin cancer, 6- to 12-monthly whole-body skin checks are critical.