Overweight and obesity rates have doubled in Australia in the past 10 years, and it is predicted that more than three-quarters of the population will be overweight or obese by 2030.1 The World Health Organization has defined obesity as a chronic disease since 1997,2 with many peak health bodies around the world following suit, including in the USA, Canada and the European Union.3–5 In Australia, however, obesity is not nominated as a chronic disease in its own right, but rather simply as a risk factor for other chronic diseases.6,7

This limited definition significantly affects the way that obesity is managed in general practice.8 Currently, there are no specific item numbers in the Medicare Benefits Schedule for obesity management, and there is no clarity around its eligibility for chronic disease management (CDM) billing.9–11 An association between obesity and poor mental health has been found, with one increasing the likelihood of the other, but there is no consensus on treatment for obesity.12–14

This study explores how Australian general practitioners (GPs) define and manage patients with obesity. We compare current practice with national overweight and obesity clinical guidelines, set by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in 2013 and The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) in 2018.15,16 We propose several modifications to them for the future.

Currently, GPs are left to manage obesity using standard consults.17 Barriers to success cited by GPs in the literature include poor knowledge and low confidence in discussing specific strategies, weight stigma threatening the doctor–patient relationship, lack of local resources and referral options, and inappropriate remuneration.18,19

In 2022, the Australian Government released its first ever national obesity strategy.20 The aim of the strategy is that ‘all Australians have access to early intervention and supportive health care’.20 This study will propose two strategies to remedy deficits in GP education and remuneration and contribute to the Australian Government’s enablers of ‘Us(ing) evidence and data more effectively’ and ‘Invest(ing) for delivery’.20

By exploring GPs’ definitions and management of obesity and attitudes towards proposed educational topics for clinicians and financial and billing solutions for patients, this study aims to inform the development of learning resources and future reviews of national obesity guidelines.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involves an online survey of Australian GPs performed in late 2022. This research had ethics approval from The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 2022/HE000242).

Participants

An email invitation was sent to 1000 GPs (randomly distributed across 72% metropolitan and 28% rural) through Australasian Medical Publishing Company data services. Due to a low response rate (~3%), the survey was also sent to and distributed by Primary Health Networks across Australia and the GPs Down Under Facebook group page. Due to this additional method of sampling, we could not ascertain the overall response rate. Participant consent was implied upon completion of the questionnaire.

Data collection

Qualtrics (XM Platform; Qualtrics International Inc , Seattle, WA, USA) was used to design and implement the online survey. In the questionnaire, participants answered multiple-choice questions about their demographics, definition of obesity and current practice in managing different body mass index (BMI) categories (for a copy of the questionnaire, please contact the corresponding author). The definitions provided were derived from those most encountered in our literature review.6,8,14 Management options given were based on the RACGP’s Guidelines for preventive activities (the Red Book)16 and the NHMRC’s Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia.15

GPs were then asked to rate the potential benefit of various educational and financial strategies on a five-point scale (where 1=very low and 5=very high). The strategies were proposed following a review of the current literature and the Medicare Benefits Schedule (July 2021).9,10,12,18,19

Statistical analysis

All survey data collected in this study were de-identified prior to analysis. Descriptive analysis was used to present the characteristics of the participants with counts and proportions (gender, age and GP experience distribution, practice location and rurality based on Modified Monash Model categories). Where relevant, Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate the relationship between categorical variables. Stata SE (version 15.1 for Mac) was used for statistical analyses (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

The survey was made available from mid-July to the end of October 2022. Of the 189 responses received during this time, 160 participants completed all the questions (84.7%). The survey completion rates of male and female GPs were almost identical (85.3% and 84.5%, respectively). Between 72.7% and 92.1% of all age groups from 18 to 69 years completed the survey; however, for those aged ≥70 years, the completion rate was 0%.

Definitions of obesity

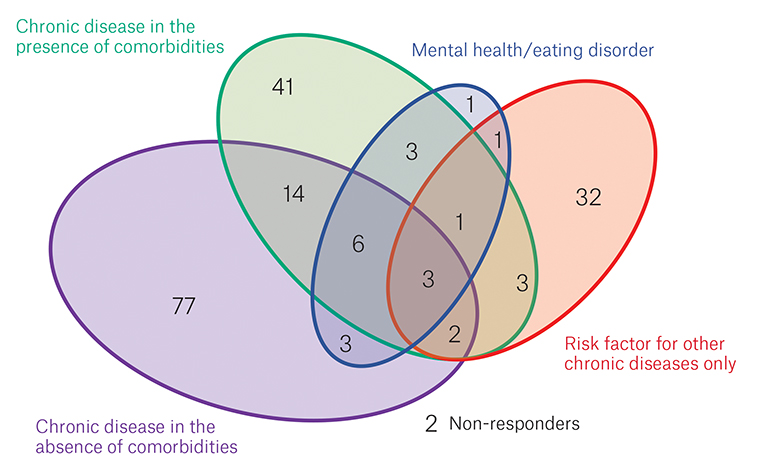

GPs only infrequently recognised obesity as a mental health/eating disorder (9.5%), whereas many defined it as a chronic disease even in the absence of comorbidities (55.6%; Table 1). Further breakdown of responses and overlap of definitions is shown in Figure 1.

Although there were no significant differences in responses between male and female participants, more metropolitan than rural GPs regarded obesity as a ‘risk factor for other chronic diseases only’ (29.6% vs 12.3%; P=0.005).

| Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants and their definitions of obesity (n=189) |

| Characteristics |

n (%) |

| Gender |

| Female |

155 (82.0) |

| Male |

34 (18.0) |

| Rurality of primary practice |

| Metropolitan (MMM 1) |

108 (57.1) |

| Non-metropolitan (MMM 2–7) |

81 (42.9) |

| State of primary practice |

| Queensland |

54 (28.6) |

| New South Wales |

42 (22.2) |

| Victoria |

36 (19.0) |

| South Australia |

18 (9.5) |

| Tasmania |

17 (9.0) |

| Western Australia |

16 (8.5) |

| Northern Territory |

4 (2.1) |

| Australian Capital Territory |

2 (1.1) |

| Definitions of obesity |

| Chronic disease in the absence of comorbidities |

105 (55.6) |

| Chronic disease in the presence of comorbidities |

73 (38.6) |

| Risk factor for other chronic diseases |

42 (22.2) |

| Mental health/eating disorder |

18 (9.5) |

| MMM, Modified Monash Model. |

Figure 1. Definitions of obesity chosen by respondents (n=189).

Prevention and management of obesity

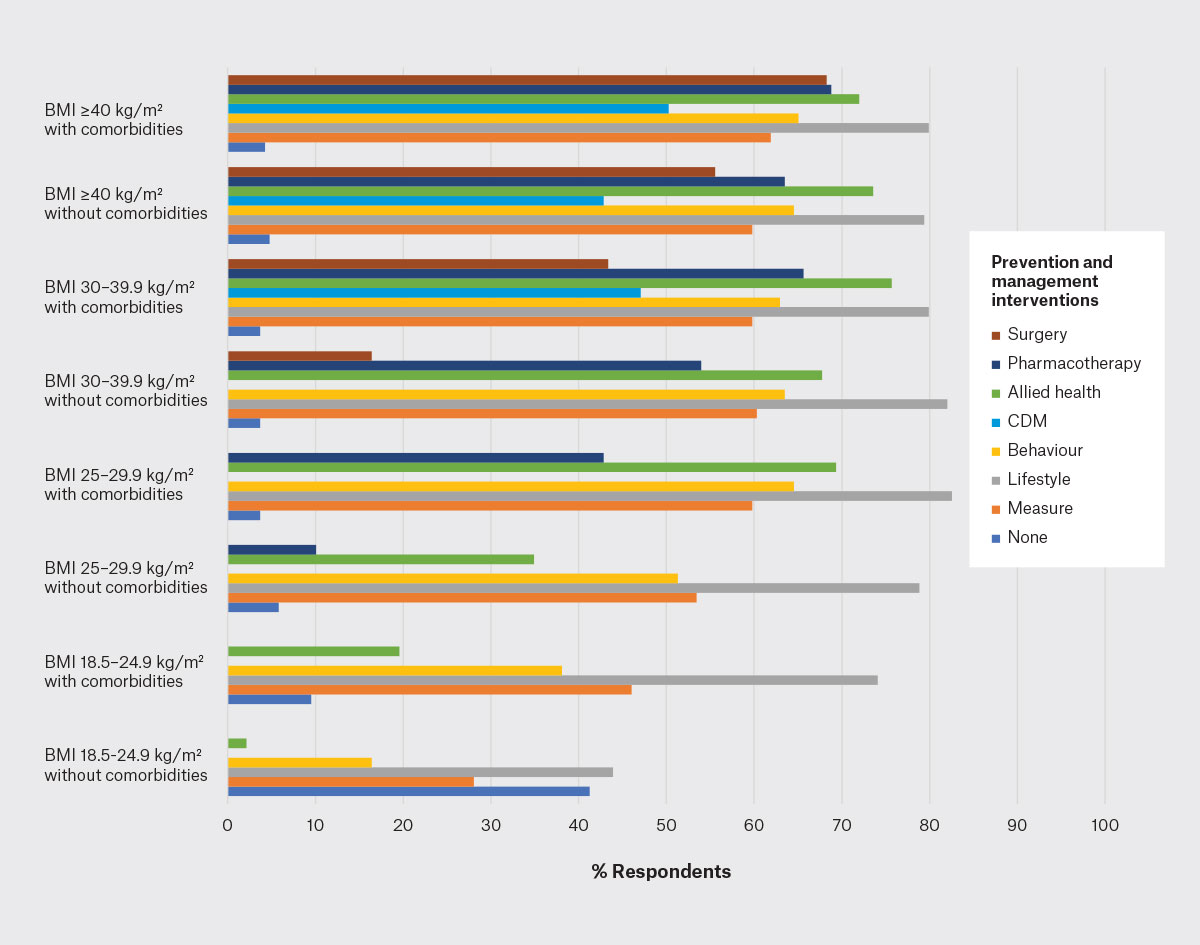

Prevention and management interventions increased as BMI increased (Table 2), but clinical practice was poorly adherent to clinical guidelines, most notably in screening and preventative activities.

Both the RACGP and NHMRC recommend that all adults, including those with a BMI <25 kg/m2 (ie within the normal weight range), be regularly measured and given lifestyle advice.15,16 As seen in Figure 2, GPs are much more likely to offer this to patients with comorbidities. For overweight adults (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2), the NHMRC recommends the above plus behaviour intervention and consideration of referral to professional programs, with additional intensive weight loss interventions for obese adults (BMI >30 kg/m2).15 The RACGP recommends similar interventions for both overweight and obese patients.16 For these patients, GPs reported little variation in management regardless of the presence of comorbidities, except in the prescription of pharmacotherapy for weight loss and referral to bariatric surgery more commonly with a high BMI and associated comorbidities. The rate of ‘no intervention’ decreased as BMI increased, but 4.2% of GPs still reported taking no action in managing adults with severe obesity and comorbidities. Many GPs used CDM item numbers for obesity, particularly for patients with comorbidities.

Female GPs were more active than male GPs in offering interventions, such as providing lifestyle advice (77.4% vs 58.8%; P=0.03) and behaviour intervention (41.9% vs 20.6%; P=0.02) to adults with a BMI <25 kg/m2; referring adults with a BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 without comorbidities to external programs (38.7% vs 17.7%; P=0.02) and for pharmacotherapy (12.3% vs 0%; P=0.03); referring adults with a BMI of 30–39.9 kg/m2 and no comorbidities for bariatric surgery (20% vs 0%, P=0.002); and referring adults with a BMI of 30–39.9 kg/m2 and comorbidities for bariatric surgery (47.1% vs 26.5%; P=0.03). The only exception was that male GPs referred adults with a BMI >40 kg/m2 for pharmacotherapy more than female GPs (79.4% vs 60%; P=0.03).

Figure 2. Prevention and management of obesity (n=189).

BMI, body mass index; CDM, chronic disease management billing on the Medicare Benefit Schedule.

| Table 2. Prevention and management strategies for obesity (n=189) |

| |

None |

Measure |

Lifestyle |

Behaviour |

CDM |

Allied health |

Pharmacotherapy |

Surgery |

| BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Without comorbidities |

78 (41.3) |

53 (28.0) |

83 (43.9) |

31 (16.4) |

|

4 (2.1) |

|

|

| With comorbidities |

18 (9.5) |

87 (46.0) |

140 (74.1) |

72 (38.1) |

|

37 (19.6) |

|

|

| BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Without comorbidities |

11 (5.8) |

101 (53.4) |

149 (78.8) |

97 (51.3) |

|

66 (34.9) |

19 (10.1) |

|

| With comorbidities |

7 (3.7) |

113 (59.8) |

156 (82.5) |

122 (64.6) |

|

131 (69.3) |

81 (42.9) |

|

| BMI 30–39.9 kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Without comorbidities |

7 (3.7) |

114 (60.3) |

155 (82.0) |

120 (63.5) |

|

128 (67.7) |

102 (54.0) |

31 (16.4) |

| With comorbidities |

7 (3.7) |

113 (59.8) |

151 (79.9) |

119 (63.0) |

89 (47.1) |

143 (75.7) |

124 (65.6) |

82 (43.4) |

| BMI ≥40 kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Without comorbidities |

9 (4.8) |

113 (59.8) |

150 (79.4) |

122 (64.6) |

81 (42.9) |

139 (73.5) |

120 (63.5) |

105 (55.6) |

| With comorbidities |

8 (4.2) |

117 (61.9) |

151 (79.9) |

123 (65.1) |

95 (50.3) |

136 (72.0) |

130 (68.8) |

129 (68.3) |

Shading indicates this is not applicable and, thus, was not surveyed.

BMI, body mass index; CDM, chronic disease management billing on the Medicare Benefit Schedule. Data are presented as n (%). |

Perceived benefit of proposed strategies

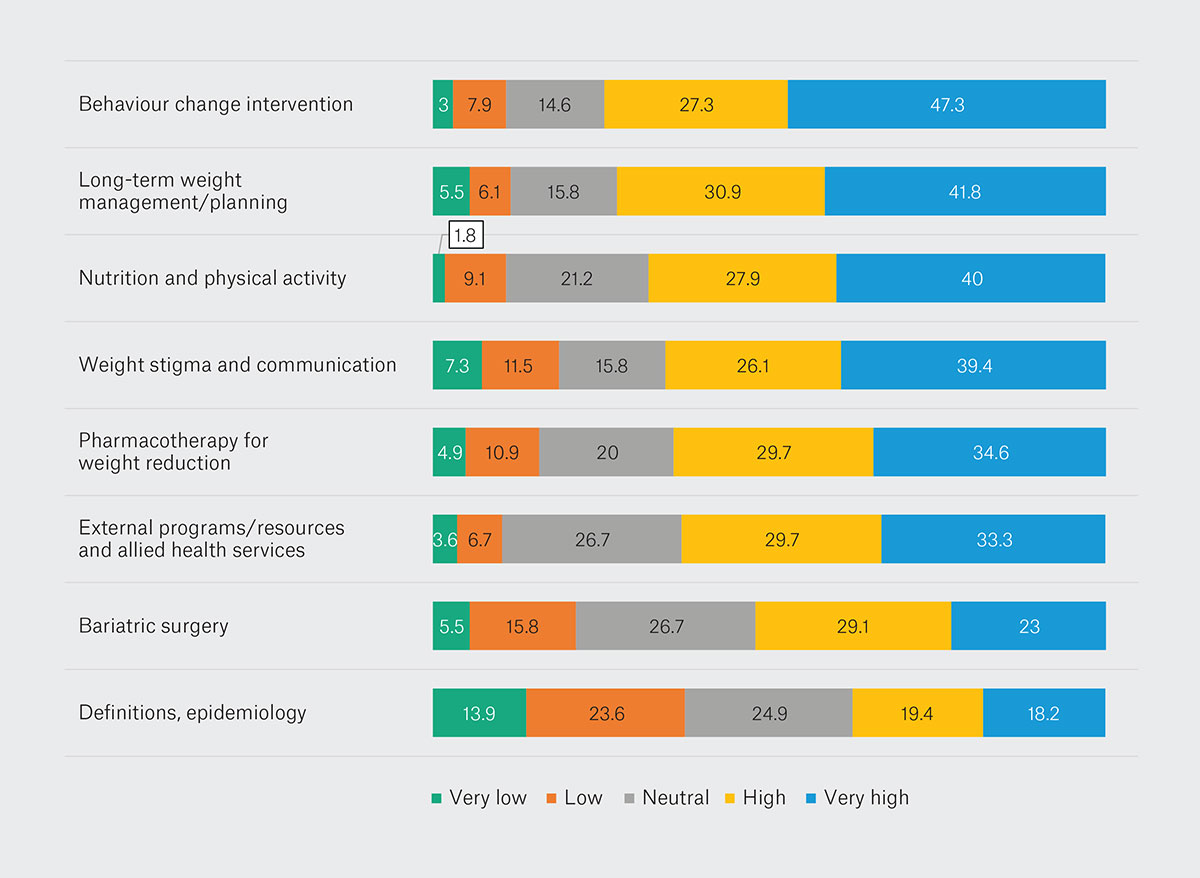

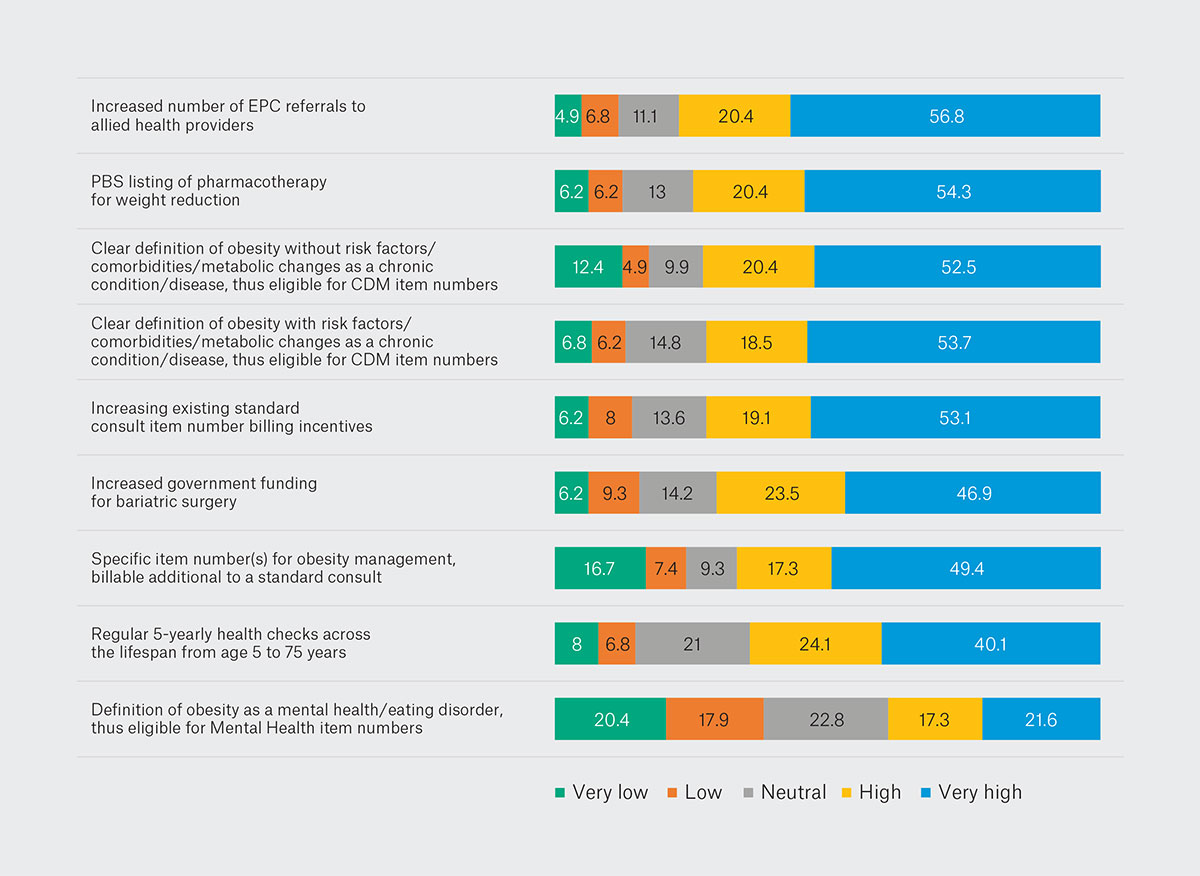

GP opinions on proposed education and financial strategies were measured on a five-point Likert scale. The overall attitude towards most strategies was very positive (Tables 3, 4; Figures 3, 4).

GPs regarded education around behaviour change (74.6% ‘high’ or ‘very high’) and long-term weight management (72.7% ‘high’ or ‘very high’) as being the most useful. They were most ambivalent about education on obesity definitions and epidemiology (37.5% selecting ‘low’ or ‘very low’ and 37.6% selecting ‘high’ or ‘very high’). Most participants perceived ‘high’ or ‘very high’ benefit for all proposed financial strategies, except for the ‘Definition of obesity as a mental health/eating disorder, thus eligible for Mental Health item numbers’.

| Table 3. Perceived benefit of proposed education strategies (n=165) |

| |

Very low (%) |

Low (%) |

Neutral (%) |

High (%) |

Very high (%) |

| Behaviour change intervention |

3 |

7.9 |

14.6 |

27.3 |

47.3 |

| Long-term weight management/planning |

5.5 |

6.1 |

15.8 |

30.9 |

41.8 |

| Nutrition and physical activity |

1.8 |

9.1 |

21.2 |

27.9 |

40 |

| Weight stigma and communication |

7.3 |

11.5 |

15.8 |

26.1 |

39.4 |

| Pharmacotherapy for weight reduction |

4.9 |

10.9 |

20 |

29.7 |

34.6 |

| External programs/resources and allied health services |

3.6 |

6.7 |

26.7 |

29.7 |

33.3 |

| Bariatric surgery |

5.5 |

15.8 |

26.7 |

29.1 |

23 |

| Definitions, epidemiology |

13.9 |

23.6 |

24.9 |

19.4 |

18.2 |

| Table 4. Perceived benefit of proposed financial strategies (n=162) |

| |

Very low (%) |

Low (%) |

Neutral (%) |

High (%) |

Very high (%) |

| Increased number of EPC referrals to allied health providers |

4.9 |

6.8 |

11.1 |

20.4 |

56.8 |

| PBS listing of pharmacotherapy for weight reduction |

6.2 |

6.2 |

13 |

20.4 |

54.3 |

| Clear definition of obesity without risk factors/comorbidities/metabolic changes as a chronic condition/disease, thus eligible for CDM item numbers |

12.4 |

4.9 |

9.9 |

20.4 |

52.5 |

| Clear definition of obesity with risk factors/comorbidities/metabolic changes as a chronic condition/disease, thus eligible for CDM item numbers |

6.8 |

6.2 |

14.8 |

18.5 |

53.7 |

| Increasing existing standard consult item number billing incentives |

6.2 |

8 |

13.6 |

19.1 |

53.1 |

| Increased government funding for bariatric surgery |

6.2 |

9.3 |

14.2 |

23.5 |

46.9 |

| Specific item number(s) for obesity management, billable additional to a standard consult |

16.7 |

7.4 |

9.3 |

17.3 |

49.4 |

| Regular 5-yearly health checks across the lifespan from age 5 to 75 years (eg additional health assessment items or expanded eligibility of existing numbers) |

8 |

6.8 |

21 |

24.1 |

40.1 |

| Definition of obesity as a mental health/eating disorder; thus eligible for Mental Health item numbers |

20.4 |

17.9 |

22.8 |

17.3 |

21.6 |

| CDM, chronic disease management billing on the Medicare Benefit Schedule; EPC, enhanced primary care; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. |

Figure 3. Perceived benefit of proposed education strategies (n=165).

Data show the percentage of respondents perceiving each of the strategies as having very low, low, neutral, high or very high value.

Figure 4. Perceived benefit of proposed financial strategies (n=162).

Figure 4. Perceived benefit of proposed financial strategies (n=162).

Data show the percentage of respondents perceiving each of the strategies as having very low, low, neutral, high or very high value.

CDM, chronic disease management billing on the Medicare Benefit Schedule; EPC, enhanced primary care; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Discussion

At first glance, there appeared to be little uniformity in the way GPs defined obesity in this study (Table 1). However, as seen in Figure 1, most GPs (82%) agreed with the definition of obesity as a chronic disease, with and/or without comorbidities, whereas 16.9% selected ‘Risk factor for chronic disease only’, the current Australian Medical Association definition for obesity,6 as their sole response. This finding applied more among rural GPs, possibly reflecting the higher rates of obesity and chronic disease (often as a result of obesity) seen in rural areas.7

As expected, the overall trend of obesity prevention and management showed that all interventions increased with BMI (Table 2; Figure 2). Despite the recommendation from both the RACGP and NHMRC for regular measurement and lifestyle advice, these are infrequently completed for patients with a BMI <25 kg/m2.15,16 Markedly increased activity in the presence of comorbidities at the same BMI range revealed that this is a major trigger for GPs to act.

For overweight adults (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2), the NHMRC recommends the above plus behaviour intervention and consideration of referral to professional programs, with additional intensive weight loss interventions for obese adults (BMI >30 kg/m2).15 In these patient groups, GP practice is largely adherent to guidelines, with higher BMI and the presence of comorbidities sharply increasing the prescription of pharmacotherapy for weight loss and referral to bariatric surgery.

Despite literature citing uncertainty around the eligibility of obesity for CDM billing,10,11 up to half of all GPs used these item numbers, particularly for patients with comorbidities. It would be useful for Medicare to clarify and communicate these criteria to better fund existing practice and encourage more consistent obesity management.

Conversely, focus on established disease and comorbidities might be contributing to the especially poor adherence to guidelines for screening and preventative activities.15,16 To meet the pledge in The national obesity strategy ‘to halt the rise and reverse the trend in the prevalence of obesity in adults and to reduce overweight and obesity in children and adolescents by at least five per cent by 2030’,20 greater support for GP preventative activities must be urgently explored and developed.

Upon further analysis, more differences in obesity management between female and male GPs were found than between any other demographics. Female GPs were significantly more active than male GPs across many domains, as outlined in the Results section. This is perhaps also reflected by the much greater number of responses received from female than male GPs (Table 1). More research might be helpful in uncovering the reasons for this discrepancy and recommending targeted education and support for male GPs in managing obesity.

The overall attitude towards educational and financial support was very positive. Most GPs (>50%) rated the perceived benefits of all but two proposed approaches as ‘high’ or ‘very high’ (Tables 3, 4; Figures 3, 4), from clinician education on behaviour change, long-term weight management, nutritional and physical activities to funding for more enhanced primary care referrals and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme listing of pharmacotherapy for weight loss. Echoing their clinical practice, GPs also asked for a clearer definition of obesity as a chronic disease eligible for CDM item numbers. Action from GP colleges, local Primary Health Networks and the Australian Government in these areas is sorely needed.

The two outliers that did not garner as much support from GPs were education on ‘Obesity definitions and epidemiology’ and funding implications for ‘Definition of obesity as a mental health/eating disorder, thus eligible for Mental Health item numbers’. Similar attitudes were seen in Australian GPs’ reluctance to define obesity as a mental health/eating disorder (Table 1), and this conviction appears quite steadfast. This could arguably be due to the view that such a classification would further stigmatise obesity and strain the patient–doctor relationship.18,19 As exploration of the association between obesity and mental health gains momentum around the world, further research would be useful to gauge shifting perspectives in Australia over the coming years.12–14

This study is not without its limitations. Although care was taken to target a diverse range of practitioners, responses were taken from a single cross-section of a relatively small subset of GPs across Australia. Due to the method of sampling, we could not ascertain the overall response rate. Perspectives of GPs who declined to complete the survey will not be known, and there might be systematic differences between those who participated in the study and those who did not. There were also limitations to the type and number of responses that could be explored in a quantitative survey. In addition to the above suggestions, future qualitative studies might allow GPs to explore their needs and perspectives on obesity management in greater depth and detail.

Conclusion

Overweight and obesity now affect two in three adults in Australia. Most GPs in this study defined obesity as a chronic disease and responded positively to proposed educational and financial strategies to aid in obesity management. The limited definition by the Australian Medical Association of obesity as a risk factor for other conditions likely hinders management options and contributes to the observed gap between clinical guidelines and current practice. Therefore, a revised definition of obesity could be the first step to improving education and funding for the management of this complex issue.