Extreme heat has historically been accepted as the biggest killer of all disasters in Australia.1 Between January 2006 and October 2017, more than 36,000 Australians died from heat-related illnesses.2 During the January 2019 heatwave in New South Wales, there was a 133% increase in the diagnosis of heatstroke-related conditions and a 63% rise in dehydration cases in emergency departments.3 Globally, extreme heat is increasingly understood as a major killer and is projected to cause increasing morbidity and mortality as global heating worsens.4,5

The year 2023 was the hottest year since temperature records began.6 In the 12 months from June 2023 to May 2024, every month had record-high global temperatures.7 Our world is getting hotter and for the health of our community, this means an increased need to manage heat-related illnesses. General practitioners (GPs) can play a pivotal role in helping mitigate heat-related effects, reducing pressure on emergency departments and improving patient care.

Many groups have developed tools to support clinicians to implement heatwave plans, including state health departments, medical colleges, Primary Health Networks and non-government organisations like Doctors for the Environment Australia and Sweltering Cities.

We conducted a review of literature and resources, including journal articles and academic reports, to provide evidence-based strategies for GPs to prevent, mitigate and manage heat-related illness in their patients while also advocating for climate action to address the underlying cause — global heating.

Discussion

Direct and indirect effects on health

The Bureau of Meteorology of Australia defines a heatwave as a prolonged period, typically lasting three days, where maximum and minimum temperatures, both day and night, are unusually high.8 The specific threshold and duration can vary by region and climate, but it generally refers to temperatures significantly higher than the seasonal average. With climate change, as heatwaves become more extreme, frequent, prolonged and intense, they are increasingly referred to as a extreme heat events (EHEs).9 Both terms describe periods of both direct and indirect effects on health, with direct effects, termed heat-related illness (HRI), including heat stress, heat exhaustion and heatstroke.

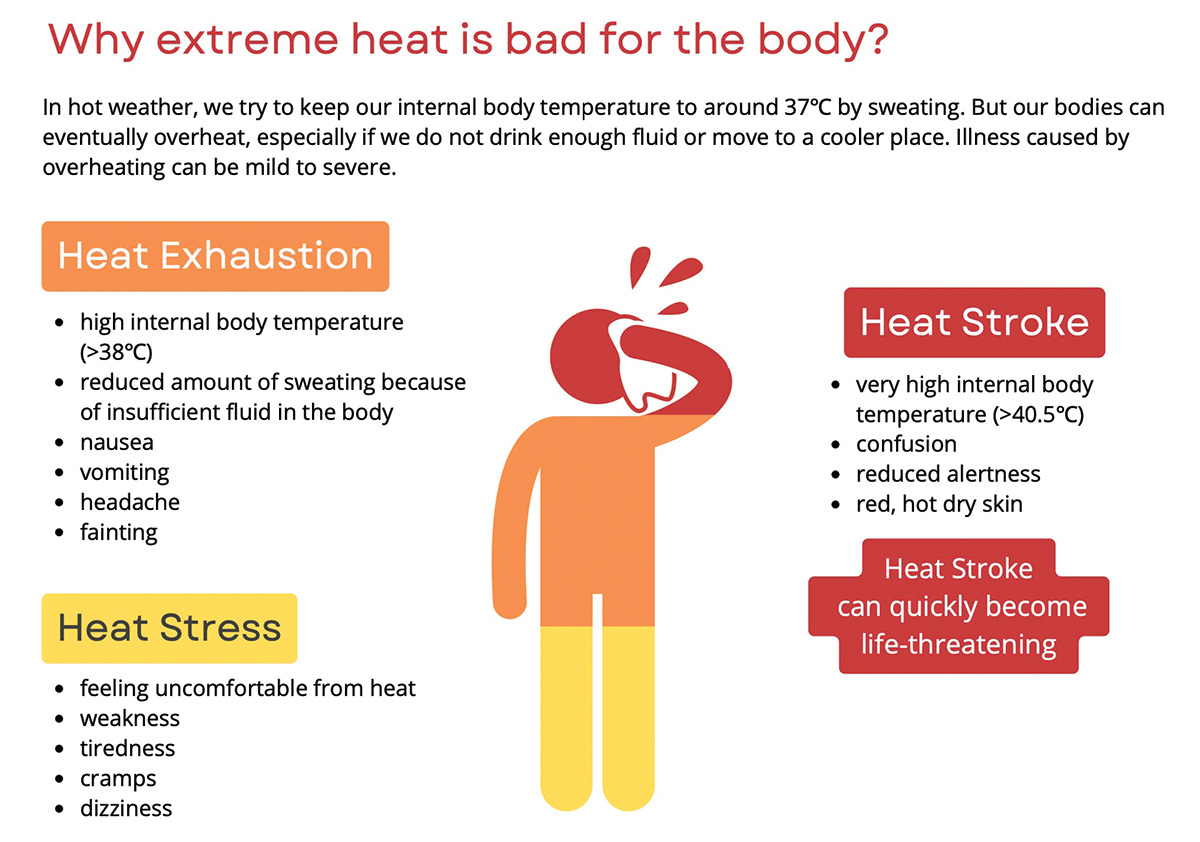

As seen in Figure 1, these should be considered a spectrum of heat effects on health, ranging from mild to severe to life-threatening.10 Patients suffering from heat stress and heat exhaustion might need medical care to prevent progression to heatstroke, a medical emergency that can be rapidly fatal due to multiorgan failure.11

Figure 1. Signs and symptoms of heat-related illness.

Reproduced from Doctors for the Environment Australia. Heat and health fact sheet. Doctors for the Environment Australia, 2023. Available at www.dea.org.au, with permission from Doctors for the Environment Australia.10

The indirect effects include exacerbations of chronic diseases reflecting the increased physiological load placed upon the body by heat, coupled with underlying pathology.12 For example, heatwaves increase the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and arrhythmia in those with underlying cardiovascular disease13 and increase the incidence of emergency department presentations for kidney disease.14 An age greater than 65 years increases the risk of all these outcomes.

Pregnant women and their unborn children face risks from heat too. A recent cohort study analysing 53 million singleton births from 1993 to 2017 across the 50 most populous US metropolitan areas found a positive association between heatwaves and increased rates of preterm and early-term births by 2% and 1% respectively.15 The study observed stronger associations in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups and highlighted the significant public health implications of heatwaves on perinatal health.

Rising temperatures and temperature variability are also associated with exacerbations of mental health conditions, including increased suicidality and hospital attendance for mental health exacerbations,16 increased violence,17 including sex offences,18 as well as interpersonal and domestic violence.19

Vulnerability to heat health impacts

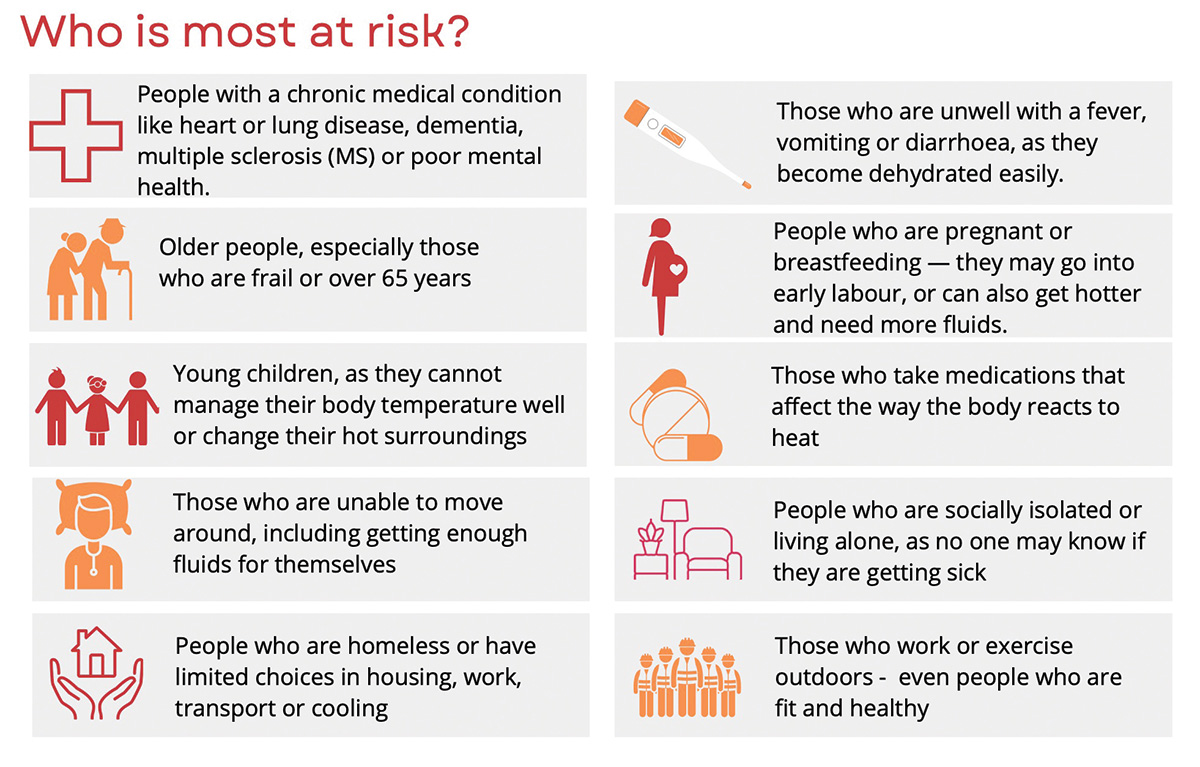

Although everyone is at risk of HRI, certain groups are more vulnerable, as highlighted in Figure 2.20

Figure 2. Groups identified most at risk of health impacts of extreme heat.

Figure 2. Groups identified most at risk of health impacts of extreme heat.

Reproduced from Doctors for the Environment Australia. Heat and health fact sheet. Doctors for the Environment Australia, 2023. Available at www.dea.org.au, with permission from Doctors for the Environment Australia.10

This vulnerability not only leads to an increased risk of adverse outcomes, but also means that these groups are more susceptible to HRI at lower temperatures. To illustrate, a person with diabetes has an increased risk of hyperglycaemia from dehydration21 and a HBA1c level >8.5 is linked with a reduced capacity to dissipate heat through sweating and vasodilation.22 These patients could be counselled to be proactive with cooling measures and avoid heat when the forecast is in the high twenties (degrees Celsius) or above.

Heat exposure, influenced by factors like the urban heat island effect,23 poses a significant risk, especially for urban dwellers, increasing vulnerability to the 73% of our population living in a major city, and outdoor workers such as labourers, park and wildlife officers and the homeless.24

Additionally, housing quality plays a crucial role in heat vulnerability, with lower socioeconomic status linked to residing in poorly insulated homes without adequate cooling options like air conditioning.25 A report by Better Renting highlights that renters are four-fold more likely than homeowners to struggle with heat.26

Rebecca, a mother of three children, shares her experience of extreme heat:

Having my first baby and navigating issues from the constant heat was very difficult. It was often over 30 degrees inside our house, and without air conditioning, we struggled to keep his room cool enough for safe sleeping. Knowing that SIDS can occur due to overheating was always front of mind. When the air was thick with smoke from the bushfires, it was impossible to open windows to cool the house, and we couldn’t go outside for days. While pregnant with my third child, it was again incredibly hot, and I found it hard to get through the day. I was constantly sweating, had heat rash, and always felt dehydrated.

Rebecca’s story exemplifies why GPs need to understand each patient’s circumstances. This ensures they can have adequate and appropriate conversations about staying safe during EHE, especially for vulnerable groups like expectant mothers.

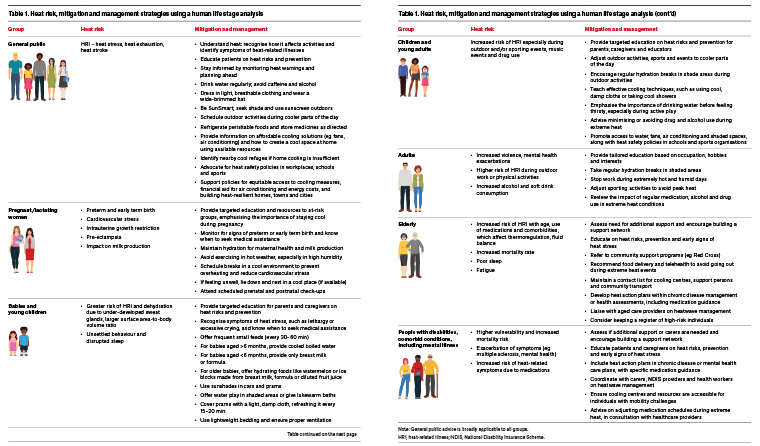

Table 1 considers heat risk, mitigation and management strategies using a human life stage analysis for vulnerable groups.

Table 1. Heat risk, mitigation and management strategies using a human life stage analysis

Cooling strategies

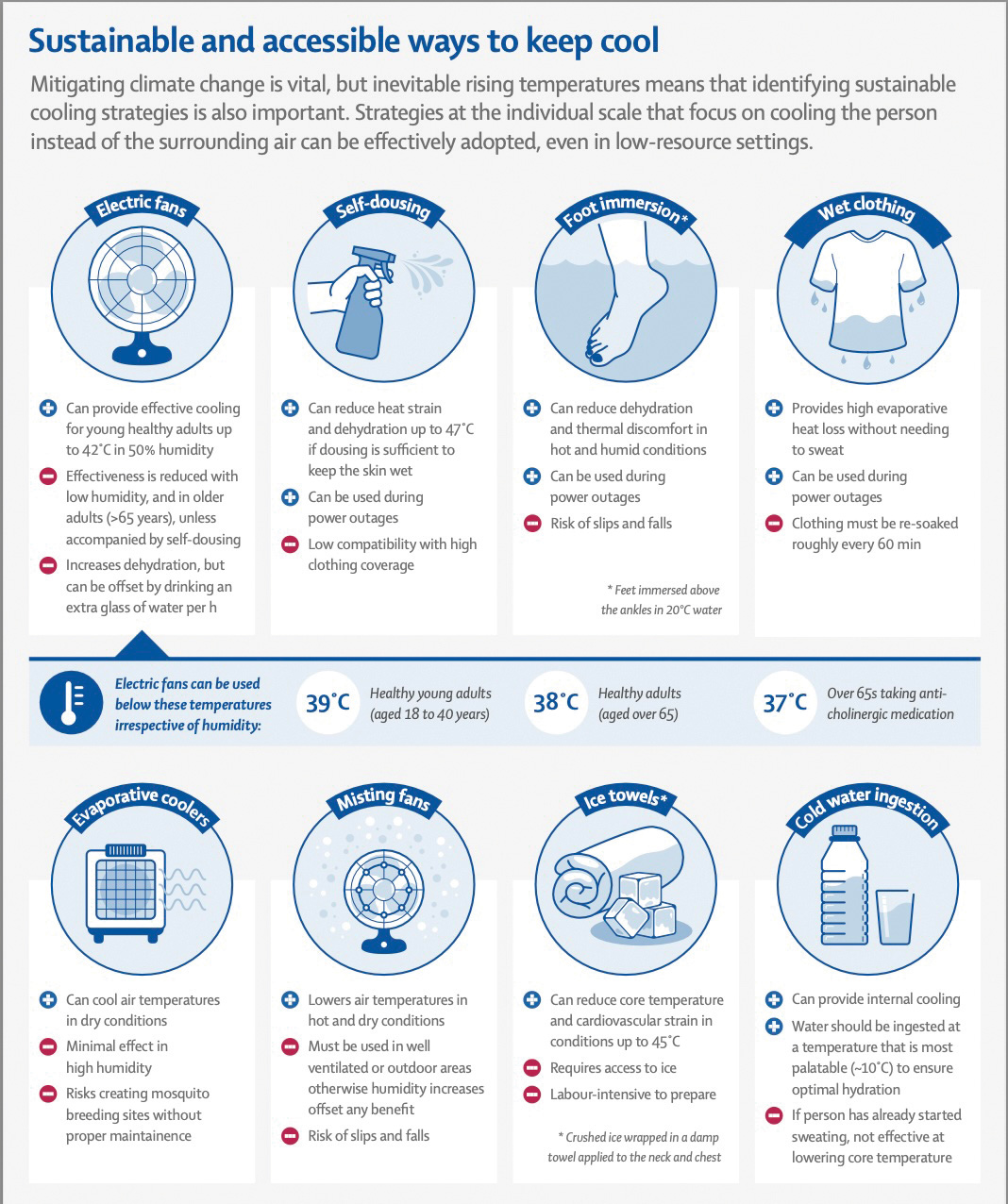

GPs play a crucial role in preparing patients for extreme heat. Key advice, as summarised in Table 1’s ‘General public’ section, includes avoiding outdoor activities during the hottest part of the day, wearing light clothing and staying well-hydrated. Figure 3 outlines new evidence-based, cost-effective cooling strategies that can help keep a home or individual cooler. For example, fans can make a room feel about 4°C cooler by speeding up sweat evaporation. They use about 5% of the electricity of air conditioners, saving money and reducing CO2 emissions. Fans can also be combined with air conditioning, allowing a higher thermostat setting to reduce costs while maintaining overall cooling;27 however, this effect is limited; above 40°C, sweat evaporation is insufficient for cooling the body.

Figure 3. Sustainable and accessible ways to keep cool.

Figure 3. Sustainable and accessible ways to keep cool.

Reproduced from Jay O, Capon A, Berry P, et al. Reducing the health effects of hot weather and heat extremes: From personal cooling strategies to green cities. Lancet 2021;398(10301):709–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01209-5, with permission from Elsevier Ltd.

Given the risk of power outages during EHEs, it is important to explore back-up options with patients, such as identifying nearby refuges. Affordable, sustainable and accessible cooling methods include using fans, self-dousing, wet clothing, ice towels and foot immersion.27,28

The Heat Watch App provides personalised risk assessments and evidence-based advice based on postcode and can be suggested to patients and carers to improve management.

Heat action plans

Incorporating heat action plans into chronic disease management plans allows GPs and practice nurses to systematically target at-risk patients and tailor their advice to the individual. Box 1 outlines a heat action planning tool. This process could include audits for at-risk groups such as pregnant patients, those on multiple medications (especially heat-sensitive ones), the elderly and socially vulnerable individuals. It could also serve as a quality improvement project for practices ahead of summer.

| Box 1. Heat action plan: Formulation tool |

1. Monitor weather reports and understand personal heat risk

- Ensure regular access to weather forecasts to plan activities that avoid heat exposure.

- Educate patients on understanding their personal heat risk based on their health conditions, lifestyle and environment.

2. Identify heat exposure risks

- Evaluate heat exposure risks related to patients’ occupations, hobbies, interests and health conditions.

3. Assess living conditions

- Gather information about patients’ living conditions, including homelessness, home cooling availability, building type, insulation and shade.

- Discuss optimal sleeping arrangements, recognising that the coolest room in a home might not be the bedroom.

4. Evaluate cooling methods

- Identify and assess available cooling methods such as fans, air conditioning and water-based cooling.

- Acknowledge that not all individuals can afford air conditioning and some live in homes without adequate cooling or water.

5. Review medications and recreational drug risks

- Evaluate and manage medication risks, particularly with angiotensin-converting antipsychotics and beta‑blockers.

- Identify and mitigate risks from alcohol and recreational drugs that can exacerbate heat-related illnesses.

6. Manage underlying illnesses

- Implement strategies to manage underlying illnesses to reduce overall health-related health risks.

|

GPs might consider familiarising themselves with heat-sensitising medications and their effects, outlined in Table 2, and conduct regular medication reviews.29,30 Patients on multiple medications or fluid restrictions are particularly vulnerable. A home medication review with a pharmacist can provide a detailed assessment, especially considering the home environment. Health assessments (for those aged 45–49 years and >75 years) also offer opportunities to discuss heat-related issues and provide relevant state-based information handouts.31–36

| Table 2. Heat-sensitising mechanism of common medications29,30 |

| Mechanism |

Drug class or subclass |

Examples of drugs |

| Reduced vasodilation |

Beta-blockers |

atenolol, metoprolol, propranolol |

| Triptans |

sumatriptan, zolmitriptan |

| Decreased sweating |

Anticholinergics – Tricyclic antidepressants |

amitriptyline, clomipramine, dothiepin |

| Anticholinergics – Sedating antihistamines |

promethazine, doxylamine, diphenhydramine |

| Anticholinergics – Phenothiazines |

chlorpromazine, thioridazine, prochlorperazine |

| Other anticholinergics |

benztropine, hyoscine, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, oxybutynin, solifenacin |

| Beta-blockers |

atenolol, metoprolol, propranolol |

| Vasoconstrictors |

ephedrine, phenylephrine |

| Interference with thermoregulation |

Antipsychotics or neuroleptics |

risperidone, clozapine, olanzapine |

| Serotonergic agonists |

sumatriptan, zolmitriptan |

| Stimulants |

amphetamine, cocaine, levothyroxine |

| Decreased thirst |

Butyrophenone |

haloperidol, droperidol |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

enalapril, perindopril, ramipril |

| Dehydration or electrolyte imbalance |

Diuretics |

furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide, acetazolamide, aldosterone |

| Drugs causing diarrhoea or vomiting |

colchicines, antibiotics, codeine |

| Alcohol |

– |

| Reduced renal function |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

ibuprofen, naproxen |

| Sulphonamides |

sulfamethoxazole |

| Aggravation of heat illness by worsening hypotension in at-risk patients |

All antihypertensives, particularly vasodilators such as nitrates and calcium channel blockers |

Nitrates: glyceryl trinitrate, isosorbide mononitrate

Calcium channel blockers: amlodipine, felodipine, nifedipine |

| Levels of drug affected by dehydration (possible toxicity for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index) |

Various |

digoxin, immunosuppressants, lithium, metformin, warfarin |

| Altered state of alertness |

Drugs altering state of alertness |

alcohol, benzodiazepines |

Treating the causes

As trusted community members, health professionals can advocate for safe environmental conditions that support health. Our efforts should focus on policies that enhance heat resilience, such as improved urban planning, increased green spaces and affordable cooling options for all. Global heating will increasingly have an effect on heat-related illnesses on our healthcare system, communities and patients.37 We have a responsibility to advocate for climate action, recognising that ongoing fossil fuel combustion is heating our planet and harming health. Coal, oil and gas are driving up temperatures and should be seen as a public health hazard.

Conclusion

GPs play a crucial role in managing heat-related health risks, especially for vulnerable populations. By integrating heat action plans into chronic disease management, reviewing medications and offering practical cooling strategies, GPs can significantly mitigate the health impacts of extreme heat. Additionally, health practitioners should advocate for systemic changes to address the root causes of heat-related vulnerability. This comprehensive approach will protect and support patients and communities from the growing health effects of global heating.

Key points

- Heat-related illnesses are rising as global temperatures increase.

- GPs have a vital role in advocating for health measures to counteract the effects of climate change.

- This article offers practical strategies for identifying, supporting and managing patients at risk from heat, including educating patients and caregivers on evidence-based cooling techniques.