Considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the biggest threat to health in the twenty-first century,

1 the effects of climate change are particularly critical for children and youth. The increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events can destroy homes, schools and community infrastructure, limiting opportunities for children’s development and wellbeing, and adversely impacting their life trajectories. Climate change significantly affects land useability,

2,3 leading to a loss of livelihoods and consequently impacting children’s wellbeing via poverty, lack of opportunities, disrupted education, malnourishment, and increased risk of physical and sexual assault.

4 Climate change also results in higher disease prevalence, food and water insecurity, and damage to infrastructure, necessitating relocation and economic strain,

5 which in turn limits children’s potential for growth and development.

In recent years, Australia has experienced several climate catastrophes (eg Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20 in Victoria, flash floods in Queensland), which have a web of consequences, with one demographic standing to be particularly vulnerable: children and youth. Women and children, particularly from priority populations who are disadvantaged and marginalised, are observed to disproportionately experience higher rates of mental health impacts compared to the general population.

6 This needs to be viewed as a serious human rights issue as children and young people have the right to be adequately protected.

The climate crisis: The mental health toll

Climate change, with its escalating natural disasters, ecological degradation and uncertain future, is not merely an environmental phenomenon but also a psychological one. Unlike past generations, whose understanding of climate change was limited and disconnected to their daily life, the youth of today are acutely aware of the implications of climate change on their futures. Over 50% of individuals report the environment as one of the most prevalent issues in Australia today, with one-quarter of those individuals reporting significant concern about climate change.

7

Evidence suggests that compared to adults, children experience more severe distress after climate events.

8 Additionally, the constant exposure to alarming news of climate change can instil profound feelings of fear, eco-anxiety and helplessness.

9–11 The loss of biodiversity, extreme weather events and the looming threat of environmental displacement cloud their formative years, shaping their worldview and sense of security.

It is estimated that around 175 million children globally are impacted by climate related disasters.

12 This is particularly relevant for marginalised communities, including Indigenous populations and those living in developing countries, who bear a disproportionate burden of climate related stressors, amplifying existing health inequities.

5,13 The compounding effects of socioeconomic disparities, environmental injustice and limited access to mental health resources create a perfect storm of vulnerability for these children and youth, placing them at heightened risk of both physical ill health and psychological distress.

14 Further, children might experience indirect effects due to their dependency on adults. These effects include the impact of climate change on their parents’ social and emotional functioning, as well as economic status, which can subsequently lead to negative consequences for children’s development and wellbeing.

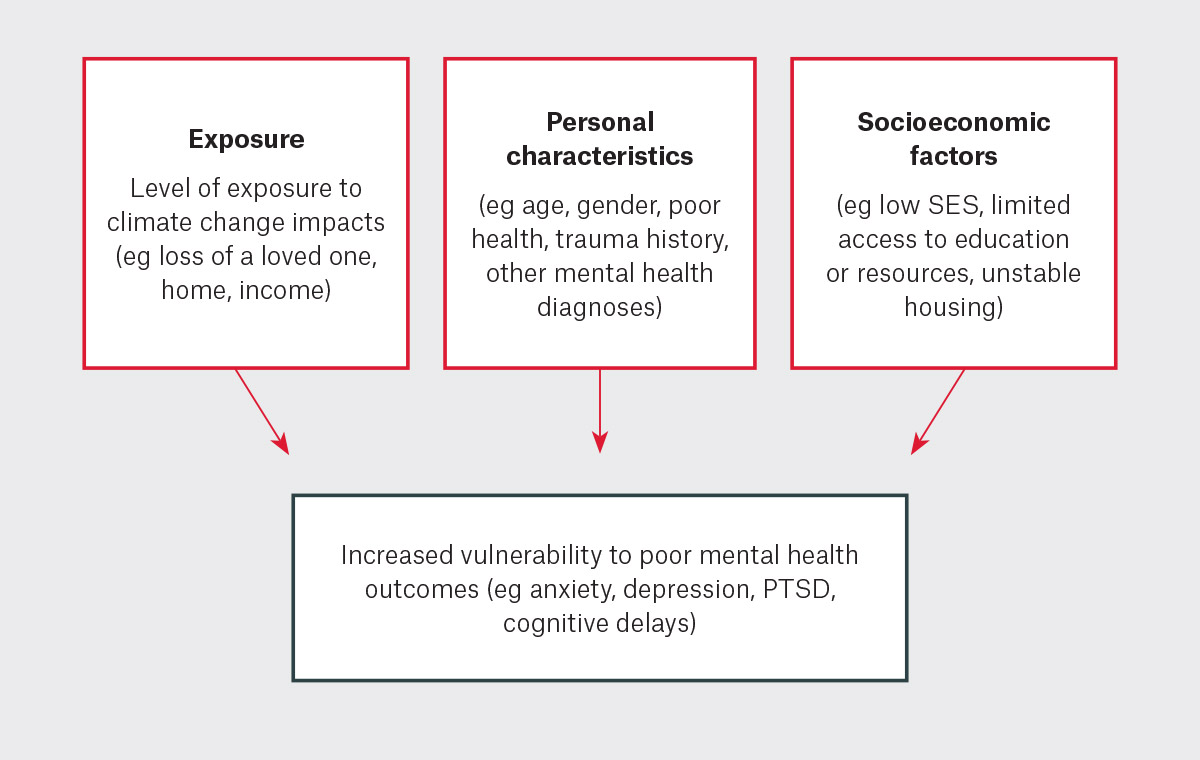

15 Factors linked to increased vulnerability for climate change impacts on children and youth are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Factors increasing vulnerability for climate change impacts on children and youth.

Figure 1. Factors increasing vulnerability for climate change impacts on children and youth.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SES, socioeconomic status.

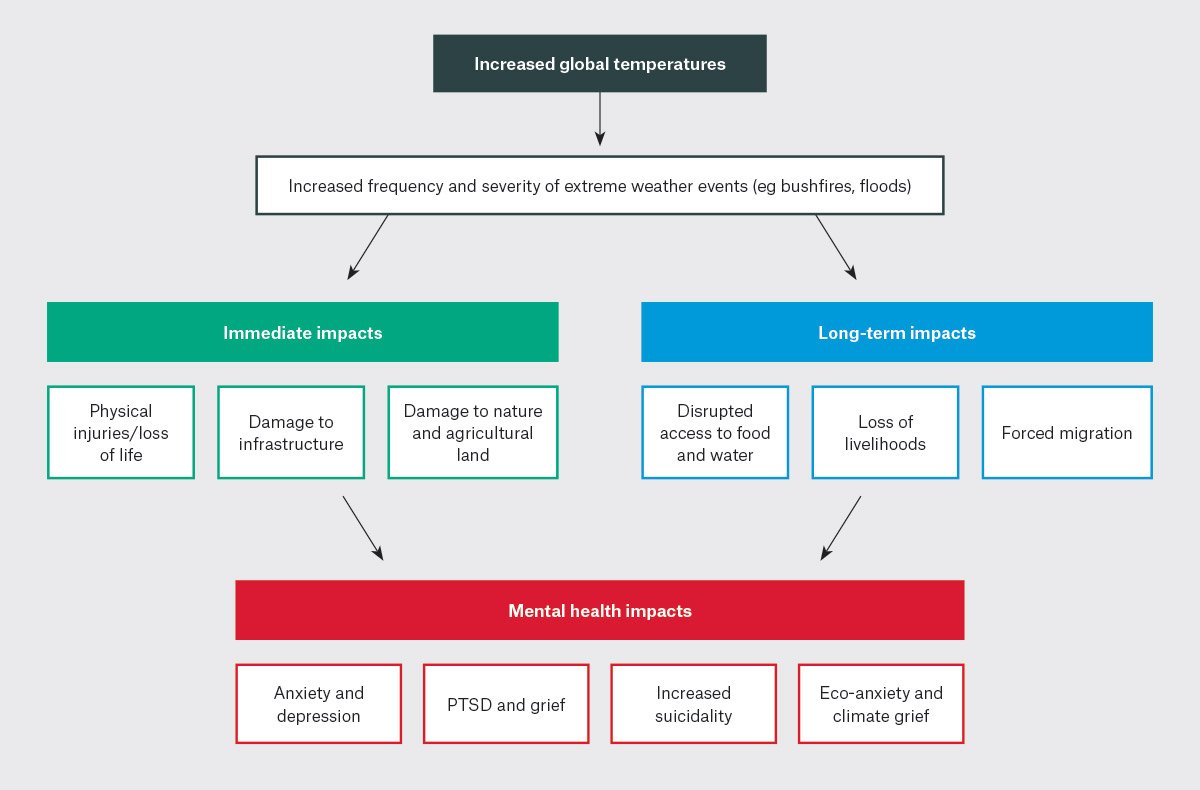

Adolescence is widely recognised as a developmental window of vulnerability, wherein most psychological disorders emerge,15 typically persisting into adulthood.16,17 The Children and Youth Report,18 produced by the American Psychiatric Association highlighted the impact of climate change on young people, and the increasing risk of a wide range of issues, from increased irritability to anxiety and impairment in interpersonal and cognitive functioning. Climate events have been associated with increased psychiatric disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders and substance use disorders.9,19 They also correlate with heightened negative emotions (ie sadness, anger) and suicidality.20 Multiple meta-analyses have revealed that a 1°C increase in mean monthly temperature was linked to an increased incidence of suicide outcomes.21 Together, this highlights the negative effects climate change has on the youth of today and underscores the need for interventions to mitigate the long-term consequences on their mental wellbeing. An illustration of climate change and its impact on mental health is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Climate change and its impact on mental health.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Acute effects of climate change

Protecting the protectors: Building resilience and empowering youth

Many young people report feeling ignored, belittled or dismissed when discussing their worries about climate change. In a recent survey, 59% of respondents reported feeling that their voices on climate change were not being heard, and among those that have talked to others about climate change, almost half (48.4%) felt ignored or dismissed.22 This highlights the need to encourage conversations about climate change and validate the emotional impact it has on youth.

Road map for practice and policy action for climate-related concerns experienced by young people

From a public health perspective, investing in approaches to reduce the effects of climate anxiety might include increasing social connections, engaging in mindfulness and self-care practices, and connecting with nature embedded within the broader context of climate adaptation and resilience planning. In practice, this might involve increasing access to, and availability of, evidence-based mental health services. To improve access and reach, it is important to implement and disseminate relevant programs by ‘going to where the children go’. This approach has been evidenced in the interventions following Hurricane Katrina, which found a 37% uptake for clinic sites compared to 98% when delivered via schools.23 Programs embedded within opportunistic settings such as the schools tend to have improved uptake as it destigmatises accessing mental health supports and also takes away potential barriers to service access such as transport, cost and parental availability to take children to clinical services.

Chronic effects of climate change

Better awareness and psychoeducation both in the community and among health professionals is critical to address the chronic effects of climate change experienced by young people. Specifically, adults need to acknowledge that youth climate anxiety is an emotionally and cognitively functional response to real existential threats. Thus, acknowledging and normalising the effect climate change can have on young people’s emotions is the first step in building emotional resilience. Caregivers and educators should actively listen without judgement and openly discuss their climate concerns. One coping strategy is termed ‘meaning-focused coping’, wherein individuals are prompted to find meaning in the climate crisis and discover more positive emotions that can reduce the effects of climate change on their wellbeing.24

From a health policy perspective, it is important to distribute the scarce resources in a targeted way to children most at risk while also providing some form of general services to all children. This calls for resource and service implementation using a ‘proportionate universalism’ framework; that is, universal services for all with additional targeted resources and supports commensurate with needs. The latter would ideally include services targeting the most vulnerable children, which might include those exposed to significant climate events;25,26 those already experiencing physical and mental health impacts of climate change or climate-related anxiety and mental health issues;27 those living in areas with limited resources;28 and those with access to limited supports. It is particularly important to empower children in the midst of hopelessness and helplessness.29 In this regard, although there are many negatives to climate change, there is also the potential to bring societies together for much needed change by giving children agency via choice and control within their settings to effect change, increasing their engagement via improving availability of information and above all, acknowledging their worries while instilling realistic hope about what actions can be taken to make a difference.

The role of general practitioners

General practitioners (GPs) must discuss any climate-related concerns with empathy and without judgement. It is important to ask about the person’s understanding of climate change and their exposure to climate-related events, whether it be personal experiences, within their family and community, or via the media. Some of the key elements in the assessment and management of climate anxiety include assessment of mental health co-morbidities and associated interventions and supports, all of which are detailed in Table 1. Assessment of the severity of symptoms, impact on their quality of life and their coping strategies are also critical. In general, a trauma‑informed and person-centred approach is recommended, including assessment of suicide risk when feelings of despair and hopelessness are expressed.30 GPs also need to be aware of available resources for their own professional development (www.psychologyforasafeclimate.org) and peer support (www.racgp.org.au/the-racgp/faculties/specific-interests/interest-groups). In summary, this review points to the need to equip young people with coping strategies, emotional intelligence and a sense of environmental stewardship, as a way of empowering them to navigate the eco-anxiety-related challenges that arise with climate change.

| Table 1. Key elements to consider in the assessment and management of climate anxiety |

| Assessment |

Interventions and supports |

| Empathic non-judgmental listening and validation. An example is the six-step ‘Climate Talk’ by Wortzel et al:31 (1) find out what children already know; (2) explain the science of climate change in a simple but complete way; (3) describe the problem but provide realistic hope; (4) discuss potential actions the child can take to get involved in climate action; (5) keep the line of communication open for future conversations; and (6) inspire a sense of wonder about the natural world |

- Link up with individuals or groups with similar values

- Support for enhancing coping including physical activity, good nutrition, mindfulness, relaxation techniques

- Self-care and related steps such as: (1) stay engaged but do not burnout or re-traumatise (eg by taking break from media/news loops); (2) do not avoid the feeling but also do not become overwhelmed by speaking about it to someone else or give voice to your feelings; and (3) use distractions or specific tangible actions to feel a sense of purpose and achievement

|

| Share resources and information about contextually and developmentally appropriate actions that can be taken. Helpful intervention themes, as per scoping review by Baudon and Jachens,32 include: (1) focus on professionals’ inner work and education; (2) foster clients’ inner resilience; (3) encourage clients to take action; (4) help clients to join groups or find social connection and emotional support; and (5) connect clients with nature |

- Focus on raising awareness, advocacy and actions to connect with nature

- Join action groups via school or the local community or national/international networks

- Make lifestyle changes that can make a realistic difference

- Instil a sense of empowerment and identify things that can be done to address the feelings of climate distress. This includes: (1) emotion‑focussed coping such as emotional expression (expressing/acknowledging the feelings); cognitive reappraisal (change the emotional impact of an emotion-eliciting situation to a more realistic and empowering view/approach); and (2) problem‑focussed coping to change the situation via problem‑solving (actions that can be taken); behavioural activation and mitigation behaviours (eg actions to reduce carbon footprint) done as individuals and also as groups to enhance effect and efficacy of action

|

Assessment of severity, impact and mental health co‑morbidities

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists offers a webinar series on climate change and mental health (www.ranzcp.org/events-learning/climate-change-and-mental-health-webinar-series) |

Effective treatment for intense climate anxiety is similar to other forms of anxiety, and specific evidence-based interventions such as the following can be helpful:

- stress and anxiety management techniques

- cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), including a specific internet‑delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT33)

- reframing and narrative therapy, including identifying, reframing and re-prioritising values, beliefs, thoughts and attitudes related to climate anxiety34

- acceptance and commitment therapy35

|

Key points

- Children and adolescents experience more severe distress after climate events, regardless of whether they have been directly impacted or whether they have been exposed to the news about such events.

- Young people are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change as many do not have well-developed emotional regulation skills and coping mechanisms when faced with stress induced by climate disasters.

- Health professionals need to be vigilant about the role of climate stress as a potential trigger or maintaining factor when dealing with children and young people presenting with mental health symptoms.

- Appropriate resources to enhance information and knowledge and evidence-based interventions are critical in supporting children and youth impacted by climate-related mental health issues.