In the twenty-first century, the international community: the World Health Organization, the United Nations, including the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the World Association of Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM) and the World Association of Family Doctors (WONCA), acknowledge primary care’s crucial contribution to disaster healthcare.1–3 The 2018 Declaration of Astana, the new global primary care declaration,2 affirms the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of accessible high-quality Health for All,4 outlining the critical role of primary healthcare in attaining high-quality healthcare around the world, and emphasises an essential role in emergencies and disasters:

A primary health care approach is an essential foundation for health emergency and risk management, and for building community and country resilience within health systems. (Declaration of Astana)2

Australian acknowledgement and recommendations from the 2023 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements Priority Action XIII: Prioritisation of Mental Health and Inclusion of Primary Health Providers in Disaster Management5 following the 2019 Black Summer bushfires supports the international call for inclusion. In this acknowledgement are Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations, valued for their contributions to effective healthcare delivery and maximising trust to local and displaced communities.5

Research conducted by Maarsingh et al6 and Starfield et al7 on the positive effects of primary healthcare on health outcomes, including increased general wellness and life span and decreased mortality, leads to a logical conclusion that the opposite is likely to occur in disasters if general practitioners (GPs) are unable to contribute to disaster healthcare. Additionally, the Sendai Framework 2015–30 point 30 (k) identifies chronic disease healthcare, the principal work of GPs, as a major disaster healthcare demand:8

People with life threatening and chronic disease, due to their particular needs, should be included in the design of policies and plans to manage their risks before, during and after disasters, including having access to life-saving services. (Sendai Framework 2015–30)8

Although high-level recognition of the value of general practice involvement in disaster health management (DHM) is clear, a dearth and inconsistency of GP inclusion in actual DHM systems still exists nationally and internationally. Very few countries have attempted integration of their primary healthcare doctors into DHM. In Australia, state/territory and regional differences in disaster management systems resulted in infrequent involvement of local GPs during the 1970s into the twenty-first century.9 This has been changing over the last decades to see Australia as one of the nations with greater integration of GPs in DHM, alongside its neighbour, New Zealand; however, there is still a long way to go.

Key DHM concepts

Integration of the multidisciplinary health responders in a systematic response to DHM improves safety and efficiency in response. When ambulance, mental health and public health professionals, emergency physicians and nurses, St John ambulance, and most lately GPs responders, work together as a team with united aims, a whole-of-health response occurs. For GPs to be integrated into disaster response, it is important to understand key DHM concepts.

What is a disaster?

Disaster definitions vary, but the essence is included in the following International Federation of Red Cross definition:

Disasters are serious disruptions to the functioning of a community that exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources. (International Federation Red Cross)10

From a health perspective, there is an imbalance in the healthcare demands and the resources available. The context of the incident can affect whether it is classified as an emergency or a disaster. For example, a bus crash in a city is an emergency, whereas in a rural area where resources are more limited, this could be categorised as a disaster (eg the Kempsey bus crash disaster).

Phases of disaster management

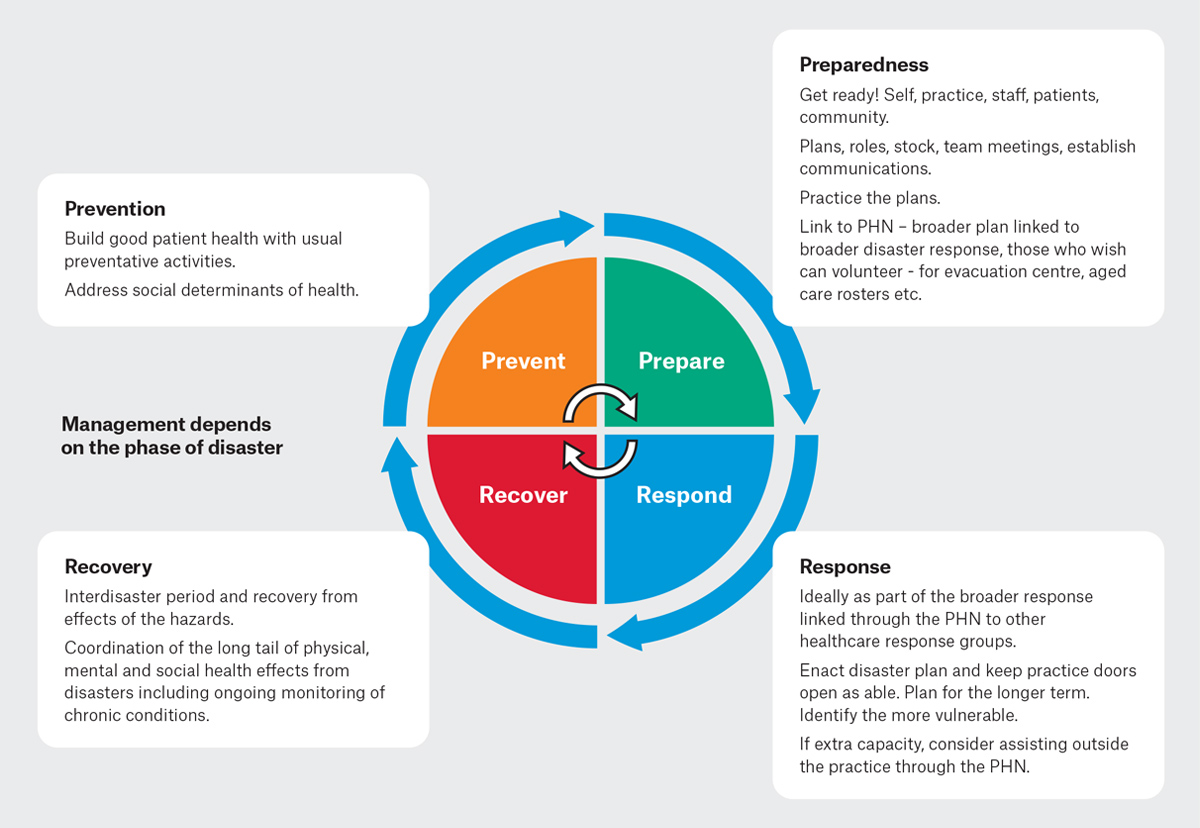

Four overlapping phases of disaster management exist: prevention (or mitigation), preparedness, response, recovery (and rehabilitation) (Figure 1). All disaster responders need to be involved in preparedness, which includes planning, before they can be effectively involved in response. GPs are one of the few disaster healthcare professionals (HCPs) who have a role to play in each phase.

Figure 1. Prevention–Preparedness–Response–Recovery (PPRR) overlapping phases of disasters and general practitioner roles.11

PHN, Primary Health Network.

How do GPs link to the broader disaster health response?

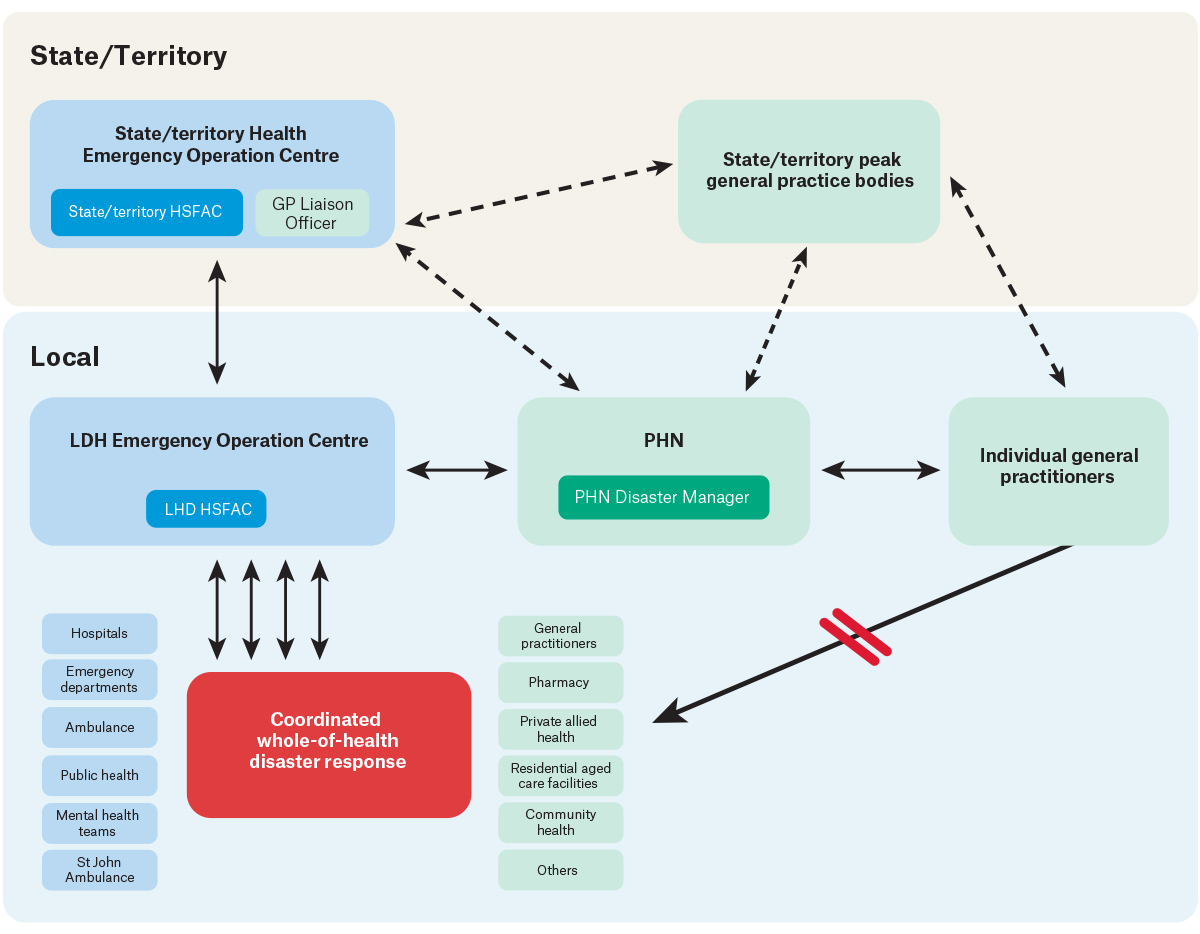

Local Health Districts (LHDs), also known as Local health networks, or hospital and health services in other states and territories, are the designated agencies that lead the health response (backed by the states and territories). The LHD Health Services Functional Area Coordinator (HSFAC) – the LHD commander – oversees the local area health response. In larger disasters, the state/territory HSFAC coordinates the health response across different local areas with local HSFACs. For GPs to be optimally included in DHM and disaster response, they need to be linked into this command structure through their Primary Health Network (PHN). This links to their LHD, which in turn links to the broader disaster system response (Figure 2). In prior disasters, GPs have contributed effectively in spontaneous response without prior inclusion in planning; however, this can rather result in a disjointed health response where GP contribution is not maximised.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of general practitioner linkage to, and communication with, the broader disaster health management response.

GP, general practitioner; HSFAC, Health Services Functional Area Coordinator; LHD, Local Health District; PHN, Primary Health Network. Dotted thinner lines indicate minor lines of communication; solid thicker lines indicate main lines of communication.

Management at the scene of a mass casualty event

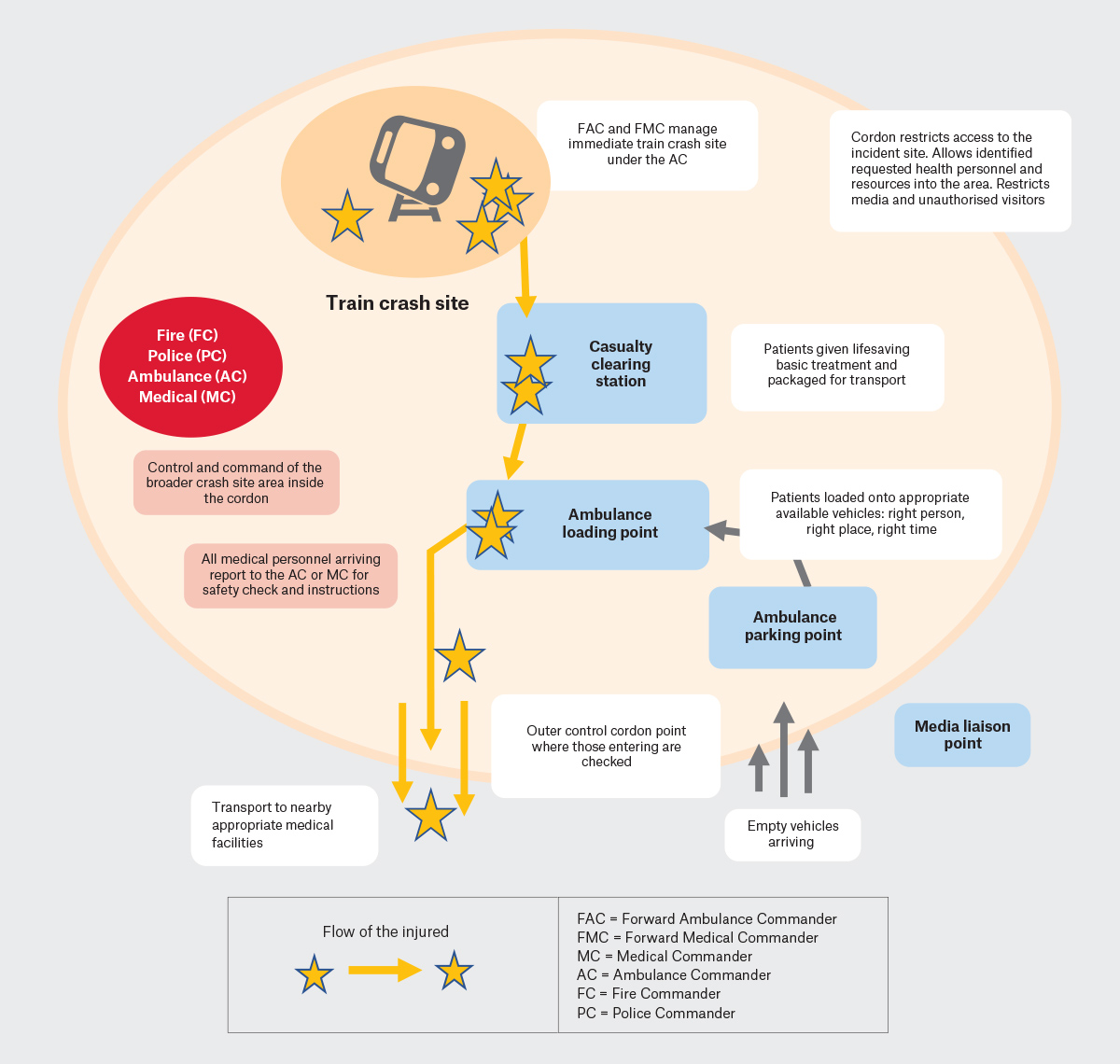

Part of the disaster response system includes a system of management of the scene of the incident involving mass casualties (eg the site of collision of two trains [Figure 3]). Major Incident Medical Management and Support (MIMMS) training is required for those HCPs attending a mass casualty incident.12 An outer cordon is established to control the flow of trained authorised required personnel to the disaster site. GPs wishing to assist have sometimes not been admitted onto the site due to lack of formal training or integration into the planning.

Activities at the disaster site are controlled by communication between the fire, police, medical and ambulance commanders, as shown in the red circle in Figure 3. The injured are move from the crash site, carried or walking, to the casualty clearing station where they are given life-saving treatment and packaged for transport to hospital. They are then taken to the ambulance loading point where appropriate vehicles move through the drive circuit to collect them and take them to hospital.12

Figure 3. Schematic example of Major Incident Medical Management and Support (MIMMS): Standardised organisation of the scene of a mass casualty incident demonstrating chain of command, the restricted access through the outer cordon, and the flow of patients.12,13

Figure 3. Schematic example of Major Incident Medical Management and Support (MIMMS): Standardised organisation of the scene of a mass casualty incident demonstrating chain of command, the restricted access through the outer cordon, and the flow of patients.12,13

Adapted from Mackway-Jones K. Major incident medical management and support: The practical approach at the scene, 3rd edn. Figure 10.4 The Silver area. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, with permission from Wiley‑Blackwell.12,13

Evacuation centres: When and how should GPs assist?

In some disasters, GPs might assist at an evacuation centre. Evacuation centres provide safety, accommodation and basic needs including healthcare to those fleeing their homes for the short term. Although evacuation centres differ substantially due to local context and the disaster itself, they are planned and regulated.14 They are under the control of a manager, as outlined in each state/territory’s State Emergency Management Plan (EMPlan) Major Evacuation Centre Guideline, and have established lines of control, communication and admission of authorised personnel to the site.

GP involvement in healthcare provision at an evacuation centre should preferably be through the PHN, linked through the LHD, to the evacuation management team. Ideally, the planning and protocols for GP involvement are established between GPs, the PHN and LHD prior to a disaster. Although in many recent disasters such as the Northern NSW floods, GPs have contributed valuable healthcare at evacuation centres (refer to Box 1), in other disasters such as the 2019 Black Summer bushfires, we saw inclusion and exclusion of GPs in different geographical regions.

| Box 1. Case study: Lismore floods |

In February 2022, my general practice, Keen Street Clinic in Lismore, was flooded to a height of two metres inside the practice. It was virtually destroyed, with the long-term result meaning that only the roof and frame and floorboards could be salvaged. The town of Lismore was similarly and catastrophically damaged. There were confronting, complex and difficult challenges in approaching the response to the immediate disaster, and then subsequent recovery.

The extent of the damage and imminent threat to life was apparent within hours of the town’s inundation. I assisted in the ’tinny army’ flood rescues – part of the spontaneous response by Lismore’s locals to rescue people and animals from flooded houses. Some of my colleagues were themselves isolated by flood waters or even in need of being rescued themselves. I was able to throw myself totally into the flood rescues and evacuation centre set up because it was apparent the buildings of our clinic were extensively damaged and the flood waters would not recede for several days – leaving me without a job!

In the evacuation centres, the local medical people organically organised ourselves into teams to provide the best care we could, when and where we could. For example, some of the Alstonville general practitioners (GPs) did their day work, and then came after hours to volunteer in the evacuation centres until late at night. Nurses, medical students, local specialists came, and we all did the best we could.

After a couple of days, the Local Health District and Primary Health Network (PHN) started to try to coordinate a more official response, and my practice GPs, nurses and reception staff agreed to part of this response. Although well-intentioned, this was perhaps the most frustrating time after the flood, as we were in under-equipped rooms (no computers, no internet, no practice software, no access to patient records, minimal equipment) and dealing with a traumatised, distressed and needy population group.

My team and I then spent the better part of 3 months at our temporary premises, using begged and borrowed equipment while we rapidly engaged a builder to do a very quick and cheap repair to the smaller of our two-clinic buildings. We had had to contemplate bankruptcy, which was a very scary and real threat. We were going to try to survive without any confidence that we could.

As an individual practice, we appreciated the PHN’s support for some funding for staff wages in the evacuation centres; however, there was no proactive government response to the destruction of community healthcare in Lismore. Along with our practice (8000 patients), the other major practice in town, The Lismore Clinic (10,000 patients), was also extensively damaged and out of action. We lost our dermatologist, two of our cardiology practices, an obstetrics and gynaecology practice, physiotherapists, dentists, pharmacists and more.

At no stage was there any coordinated response at either state or federal level aimed at restoring the healthcare provisions in Lismore. As I write those words, I remain, two years later, still quite shocked at this. It actually took many, many months of campaigning, with the help of the Australian Medical Association in particular, but also The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Australian College of Remote and Rural Medicine, Rural Doctors Network and Rural Doctors Association, and maintaining media interest, to secure some more meaningful government funding to allow the repairs required to resume usual service. In the meantime, however, we were eligible to apply for the $50,000 small business grants. A welcome amount but minimal compared to our losses of $2 million dollars. The amount was the same that my friend and local barber was eligible for with his one-room operation.

Dr Nina Robertson, May 2024 |

The essential role of GPs in disasters: Keeping the practice doors open

Finally, and most importantly, the foremost role for GPs is keeping their practice open and maintaining GP services to the local community. The major volume of disaster healthcare is chronic disease management including continuity of medications.15 GPs can prevent overloading of emergency departments (EDs), reserving them for higher acuity injuries.9 During Hurricane Katrina and the Christchurch earthquakes, thousands of evacuees were managed by GP teams keeping EDs more accessible.16 During the 2022 Lismore floods, the reverse was seen, with over 75% of general practices flooded and unable to see their patients onsite. Numerous patients sought primary healthcare at evacuation centres and the local ED.

Why link to the local PHN in disasters?

PHNs are the operational bodies linking GPs to disaster response. Around Australia, there are 31 PHNs linked to corresponding LHDs. PHNs support general practice in a variety of ways and work with the LHDs in their region. This makes PHNs the logical ‘go to’ organisation for LHDs seeking information on what is happening on the ground during a disaster, and alternately for GPs to communicate back to the LHDs (eg requesting assistance in accessing extra medical resources; Figure 2). Importantly, PHNs enable GPs to work within the recognised ‘chain of command’ emergency systems. It is essential GPs connect with their PHN to facilitate this connection.

Until recently, there has not been a formal role for PHNs in DHM, although many PHNs have taken the initiative to link in with the formalised health disaster response structures to ensure better preparedness and coordination during disasters and support GPs.17 Table 1 outlines initiatives undertaken by PHNs to support GPs in DHM.

| Table 1. PHN initiatives in each stage of disaster health management |

| PHN initiative |

Descriptor and examples |

| Stage of disaster: Prevention |

|

| Measures to improve community health (eg vaccination) |

Improves health resilience of local population in disasters |

| Stage of disaster: Preparedness |

|

| Development of GP resources, disaster HealthPathways and PHN website information on disaster preparedness |

HealthPathways ‘Preparing a General Practice for a disaster’ and ‘Preparing Patients for a disaster’, General Practice disaster toolkit, cold chain management and links to other resources (eg www.nbmphn.com.au/Health-Professionals/Disaster-Planning-Response-and-Recovery/How-to-prepare-your-practice-for-a-disaster) |

| ‘In practice’ support to general practice in disaster and emergency planning |

Support with emergency and business continuity plans or specific scenarios (eg cold chain management). All-hazard, but also specifically flood, mass casualty, cyber (depending on local risk) (eg www.nbmphn.com.au/getattachment/60d533fd-c937-4db0-b55b-405b369a6574/631_0323-Disaster-Management-Toolkit_fillable_Final_.pdf) |

| Coordination of registers and training for GPs with interest in DM roles (eg working at evacuation centres) |

PHN undertakes required credentialing checks, develops and coordinates information, resources and training for GPs to support the role |

| Offering different levels of training and education opportunities for GPs in DM |

Regular training and exercise opportunities including MIMMs training and PREPARE training (GP-specific disaster training) |

| Dedicated PHN Emergency/Disaster Manager |

Coordinates PHN disaster activities and a good point-of-contact for GPs |

| Development of PHN disaster plans/internal protocols defining how PHNs support primary care in disasters |

Can be customised to a local region and capacity of primary care and PHN |

| PHN participates in ‘whole-of-health’ disaster exercises with LHD |

To test GP plans in a disaster response scenario |

| Coordination of GP DM advisory and interest groups |

To inform PPRR activities and identify GPs with special skills |

| Advocacy for integration of a GP/PHN role in broader health disaster response plans (state and local) including a clear chain of command protocols for GP involvement |

This is so all sectors understand GPs’ role in disasters, including what is in and out of scope, and how PHNs can coordinate the primary care response. GPs/PHNs work within the EM structure and know when to trigger GP involvement in the broader response |

| Integration of GPs/PHN into formal EM regional governance including on disaster committees and joint strategic planning |

PHNs/GPs at the planning table rather than having an unplanned response. PHNs advocate for role of GPs and identify opportunities, address gaps and provide solutions |

| Establish PHN linkage with LHD EM to facilitate cooperation and regular communication |

Coordinated and planned education, information on potential upcoming disasters |

| Collaboration with other EM and community partners |

Coordinated and connected messaging in EM and support of vulnerable communities |

| Communications strategy |

Sharing information and identified sources of truth |

| Funding applications for disaster management |

For preparedness, training, resource development, response activities or recovery and resilience initiatives, and for GP funding for disaster activities |

| Stage of disaster: Response |

| Collection of information from general practices to identify immediate needs and operational status including ability to stay open or provide telehealth services |

Provides a picture of what is happening to primary care within the impacted region and informs overall response to a disaster. Allows for identification of gaps, needs and solutions at the individual and regional level |

Real-time traffic light map of operational status of local health services

Online for patients, GPs and emergency services to see |

Green/orange/red capacity rating of local hospitals, GPs, pharmacies, RACFs with details of opening hours, relocation, etc |

| PHN coordination of two-way sharing of localised information, messages and intelligence between primary care providers and the broader health emergency response team |

Supporting better overall ‘whole-of-health system’ organisation of services. Can consider how to best address current or expected patient needs and service demands |

| PHN provides up-to-date sit reps (situation reports) for GPs on the disaster and distributes primary care disaster resources as appropriate |

This keeps GPs abreast of the disaster situation, facility evacuations and matters impacting their practice |

| Up-to-date information for GPs via HealthPathways ‘General Practice Management during a Disaster’ and the PHN website |

Information about support during disasters including disaster telehealth item numbers, continued dispensing, patient support and links to emergency agency information |

| Coordination/activation of GP Disaster Response team as appropriate and triggered via agreed chain of command |

Rostered to attend local evacuation centres as an expected responder |

| Direct support of affected practices |

Phone calls, advice, resources, delivery of funding and advocacy for primary care |

| Knowledge of local population health and social determinants |

GP/PHN local knowledge can assist responders to identify those at higher risk |

| Coordinate disaster telehealth response allowing patients to access telehealth services from any GP during that period |

Alerting practices when disaster telehealth items are triggered. Publishing non-impacted GPs’ availability to provide telehealth for patients unable to access their own GP |

| Engagement and support of pharmacy |

Particularly relevant to operations and continued dispensing |

| Stage of disaster: Recovery |

| Targeted PHN support for practices most affected |

Workforce support in aftermath, providing disaster grants to practices and advocacy |

| Coordinated communication strategy and provision of recovery resources |

Communicating to GPs that there is support available for disaster-affected patients (eg extra psychologist sessions and specific HealthPathways [eg ‘Post Natural Disaster Health’]) |

PHN/GP inclusion in operational debriefs with other organisations

Review PHN planning with lessons learned |

To identify how processes could be improved, including future GP involvement in PPRR |

| Ongoing support of general practice needs in months to years post disaster |

This might include mental health and wellbeing support for GPs or advocacy to address issues identified by GPs |

| PHN representation on recovery committees. Support of community and allied health patient recovery activities |

Deployment of PHN commissioned services to recovery centres and advocacy to avoid duplication and gaps in recovery service provision |

| Coordination of funding of community recovery grants |

Matching local needs and other community recovery activities to maximise benefit |

| DM, disaster management; EM, emergency management; GP, general practitioner; LHD, Local Health District; MIMMS, Major Incident Medical Management and Support; PHN, Primary Health Network; PPRR, Prevention–Preparedness–Response–Recovery; PREPARE, Primary care Resilience through Emergency Preparedness for All-Hazard ResponsE (disaster management training for primary care providers); RACFs, residential aged care facilities. |

The strength of a ‘whole-of-system’ response during disasters and inclusion of primary care in the disaster management system is now being formally recognised. The Federal Government has designated emergency preparedness and response as a core policy priority for PHNs from mid-2025. In addition, in some states, the role of PHNs has been written into the State Health Services Emergency Support Plans. This recognises PHNs, as first points of contact on primary healthcare coordination matters and service availability during emergencies, as part of the overall coordinated response. This formalises the already active role PHNs play in some regions and provides the authorising environment for GPs to be involved in disaster management at a local level via PHNs.18

The role of GP peak organisations during disasters

GP peak organisations including The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), The Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, Australian Medical Association, Australian Indigenous Doctors Association and the Rural Doctors Association, also have key roles in DHM by providing national consistency, guidelines, policy, education, disaster health resources and advocacy, as well as providing support for individual members. The RACGP Expert Committee for Practice Technology contributes to the RACGP disaster activities and is currently updating the Managing Emergencies guide.19 The Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association and the Australian Association of Practice Managers also have key roles.

Case study: Lismore floods

Although substantial change in GP integration into DHM is occurring, it is still inconsistent nationally. Lessons learned from GPs in each disaster are crucial for improving and consolidating the inclusion and valuing of GPs as the cornerstone of DHM. In northern New South Wales, the highest flood level was recorded in Lismore in February 2022, and was 2.29 metres (20%) above the previous record in 1974. It was Australia’s costliest disaster20 and impacted more than 75% of Lismore general practices.21

The case study on Lismore Floods (Box 1) highlights the experience of local GPs and has valuable lessons for informing future planning. It has already prompted development of national guidance on GPs working in evacuation centres by the RACGP.22 The case study demonstrates how GPs supported their patient community from outside the formal disaster response despite their own losses. Prioritisation of general practice businesses was unrecognised. There was no consideration of sustaining long-term GP services in Lismore. GP organisations campaigned to support funding for GPs, but this should be programmed into existing systems.

Conclusion

Many lessons have been learned from the Lismore floods and previous disasters. Systems for GP integration into DHM exist and are being established in some localities; however, there is no handbook, and there is a long way to go.

It will take concerted and coordinated campaigning by our representative bodies for the lessons of Lismore to be heeded and for the necessary change to occur to avoid such disaster impacts in the future. (Dr Nina Robertson 2024)

To provide effective care for patients and the local community when disasters strike, it is essential that GPs understand the changing field of DHM. That includes knowledge of the systems of DHM that come into play, and how GPs interact with these through the PHNs, so that disaster health response in a community can be a coordinated whole-of-health response.

To be prepared for a disaster, GPs need to do two things: have a practice disaster plan17 that they practise; and have a conversation with their local PHN prior to any disaster. In locations where the PHNs are still in the early stages of planning, GPs need to understand and incorporate this into their own planning, and be flexible until the PHN has more robust disaster planning in place.

Key points

- The evidence and expert opinion support an essential role for GPs in DHM.

- A complex DHM system activates during a disaster response.

- PHNs are the operational link between GPs and the local disaster response.

- The time to prepare is before the disaster. Do two things: develop a practice disaster plan; and link with your PHN before a disaster event.

- GPs with a special interest in DHM should consider doing Primary care Resilience through Emergency Preparedness for All-Hazard ResponsE (disaster management training for primary care providers; PREPARE) or MIMMS training.