It is estimated that between at least 64,000 and 96,000 young Australians aged between 15 and 24 years might identify as transgender.1 A recent systematic review of the literature demonstrated gender-affirming hormone therapy improves psychological wellbeing and quality of life in transgender individuals;2 however, gender-affirming hormone therapy can be difficult for patients to access.3–5 Many young transgender, gender-diverse and non-binary (TGDNB) people report negative experiences with health professionals, including transphobic comments and refusal to provide care.4–7 Although general practitioners (GPs) can provide gender-affirming care (GAC) to adult patients under an informed consent model of care,8,9 it is often still provided in specialist services by endocrinologists or sexual health physicians.

As more TGDNB patients seek GAC,10 it is important for Australian GPs to understand the barriers and facilitators these patients experience when accessing healthcare within general practice and when seeking referral to specialist services.

It is also important to increase GP awareness of the services that are available, and ensure that GPs can access referral pathways and partner with specialist services to provide more holistic care.

When TGDNB patients experience insensitive care from healthcare professionals, they are less likely to access all forms of healthcare. A national survey found that when TGDNB patients face gender insensitivities from healthcare professionals, this limits their uptake of healthcare, including mental healthcare, GAC and testing for sexually transmitted infections.3 It is therefore important that all healthcare professionals are respectful of gender-diverse patients and aware of simple strategies that can be helpful, such as asking for pronouns, preferred names and simple inclusive signage in practice spaces.

In June 2019, a multidisciplinary, adult GAC service was commenced at an urban sexual health clinic (SHC), using a model of informed consent. Holistic GAC was provided by doctors, nurses, counsellors, psychologists and a dietitian. The service also has access to other specialties onsite, on a consulting basis.

This service was set up using best practice principles, with a preference for GP referral. The service was free to access as it was located within a SHC.

In 2022, we surveyed GAC patients to explore their experiences of care provided and the facilitators and barriers to accessing care. Patients were asked about their experience of gaining a GP referral and any difficulties they experienced in accessing care. They were also asked about the importance of gender-diverse inclusive signage, as well as the experience of being misgendered by healthcare practitioners.

Methods

Following a literature review and discussion with the multidisciplinary team, a research electronic data capture (REDCap) questionnaire was developed, reviewed by The Gender Centre and piloted (The Gender Centre is a NSW-based multidisciplinary service that supports the transgender and gender-diverse community; www.gendercentre.org.au). REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data-capture tools hosted at the Northern Sydney Local Health District.11,12 Patients who had attended the SHC for GAC on more than one occasion were eligible to participate. Questionnaires were offered in person to all eligible GAC patients who attended the clinic between January and April 2022, and email invitations were sent to the remaining patients who had not attended during that time frame. Patients attending for an appointment were invited to participate. Invitations were offered in person by a medical student using an ethics approved script. Participants could choose to use the clinic iPad or an email link could be sent to their own device, and they were encouraged to complete the questionnaire in the waiting room. Demographic information was collected, and questions included how they found out about the clinic, difficulties encountered seeking referral, perceptions of the clinic, and their experience accessing and receiving care. Most questions were single-choice answers with the option of free-text responses. Descriptive analysis was performed on the quantitative and qualitative data.

This research was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (NSLHD HREC; #2021/ETH11775).

Results

Demographics

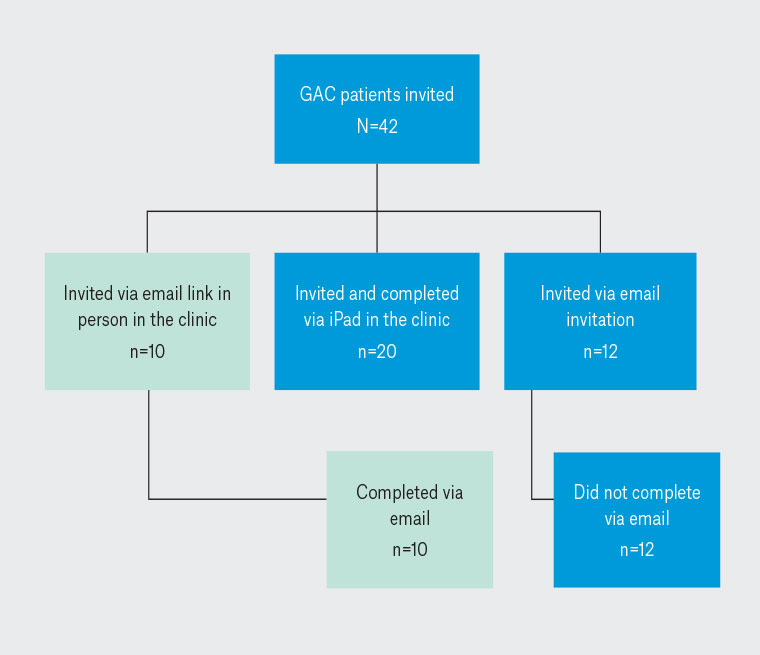

Of the 42 patients who were invited to participate in the research, 30 completed the questionnaire (71%) (Figure 1). Of the 30 participants, 53% were transwomen, 40% transmen and 7% identified as non-binary. Their ages ranged from 18 to 60 years, with a mean age of 25 years. Refer to Table 1 for terms and definitions.

Figure 1. Flow chart of patients invited to participate and those completing the survey.

GAC, gender-affirming care.

| Table 1. Glossary of terms and abbreviations13 |

| Term/abbreviation |

Explanation |

| AFAB |

Assigned female at birth |

| AMAB |

Assigned male at birth |

| Cisgender |

Identify as the gender assigned at birth |

| Deadname |

An informal way to describe the former name a person no longer uses because it does not align with their current experience in the world or their gender. Some people might experience distress when this name is used |

| GAC |

Gender-affirming care |

| Misgender |

An occurrence where a person is described or addressed using language that does not match their gender identity. This can include the incorrect use of pronouns (she/he/they), familial titles (dad, sister, uncle, niece) and, at times, other words that traditionally have gendered applications (eg pretty, handsome) |

| TGDNB |

Transgender, gender-diverse and non-binary |

Referral process

Many patients (40%) had reported difficulty accessing GAC elsewhere. Only 10% said they did not have difficulty and 50% reported this question was not applicable to them, commenting that they had not sought care elsewhere. Many patients provided comments that demonstrated the difficulties experienced. One of the difficulties accessing GAC that was reported included a lack of knowledge from medical professionals:

Lack of knowledge/understanding from other healthcare establishments/professionals. (Participant 1, aged 20 years, non-binary, AFAB, he/him/they/them pronouns)

So even informed medical professionals in my area weren’t sure what to do with me when I came in asking for options for gender affirming treatment. (Participant 28, aged 20 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Another difficulty was the perceived requirement for, and difficulty accessing, a psychologist diagnosis:

I got a referral from my GP to the gender centre so that I may get access to a gender dysphoria diagnosis as I wasn’t aware of the informed consent route to getting hormones. I then waited 3 months… (Participant 15, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Long and complicated referral processes were described:

Other clinics tend to make access to hormones extremely difficult with a long and complicated waiting process. (Participant 9, aged 20 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

The wait times are hell. Without (the service) I would have had no counsellor/psych to talk to when I desperately needed one. (Participant 11, aged 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

The cost of consultations with GPs and other health professionals was identified as a barrier:

Pricing of consultations is too expensive, especially considering when someone is only looking for an initial consult to find out additional information. (Participant 21, aged 19 years, female, AMAB, she/her/they/them pronouns)

Organising with endocrinologists elsewhere is an effort and expensive. (Participant 11, aged 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

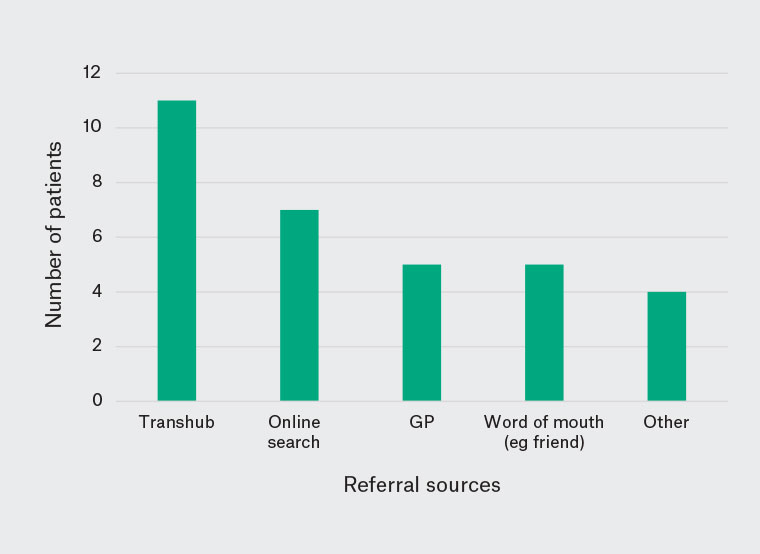

Only 17% found out about the service from their GP (Figure 2). The TransHub website (www.transhub.org.au) was the main source of information about the service (37%), followed by an internet search (23%). TransHub is a resource for all transgender people in New South Wales (NSW), allies and health providers; www.transhub.org.au, delivered by ACON, NSW’s leading health organisation specialising in community health, inclusion and HIV responses for people of diverse sexualities and genders.

Figure 2. How patients report that they heard about the GAC service (ie How did you hear about the service?).

GAC, gender-affirming care; GP, general practitioner.

Most said they were able to obtain a GP referral (63%), with only four patients saying they had difficulty getting a referral.

Privacy and confidentiality concerns were highlighted by participants seeing a GP who saw other family members:

I had a family GP so didn’t go there (as I was worried about being outed), still to this day that GP misgenders me, knowing that I’m trans. I tried going to another GP but they said they don’t know me well enough to refer me etc. (Participant 11, age 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

There were also comments from those who perceived GPs to be acting as gatekeepers:

GPs are really gatekeepy about giving trans people referrals for hormone treatment. (Participant 12, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Patients also reported that GPs appeared to be uncomfortable with TGDNB patients:

…And it’s hard to find a good GP who knows how to deal with trans patients. Getting dead named and misgendered makes it hard to me to go in the first place. (Participant 12, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

I live … in a mostly conservative area, it’s all very ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ kind of thing, (Participant 28, aged 20 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

GP was clearly uncomfortable and strongly preferred referring counselling for anxiety/depression rather than dysphoria. (Participant 29, aged 29 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

In contrast, one patient commented on a positive experience accessing the service via a GP when the GP was knowledgeable about referral pathways:

The day after coming out to my family as trans, we took me to a GP to ask them about accessing gender affirming care, and they told us to go here. (Participant 4, aged 20 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

Another commented how seamless it can be when GPs are happy to provide a referral when requested:

I made the choice myself to go but I was required to have a referral from my GP. I just made an appointment with my GP to get a referral and the rest was no problem. (Participant 7, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

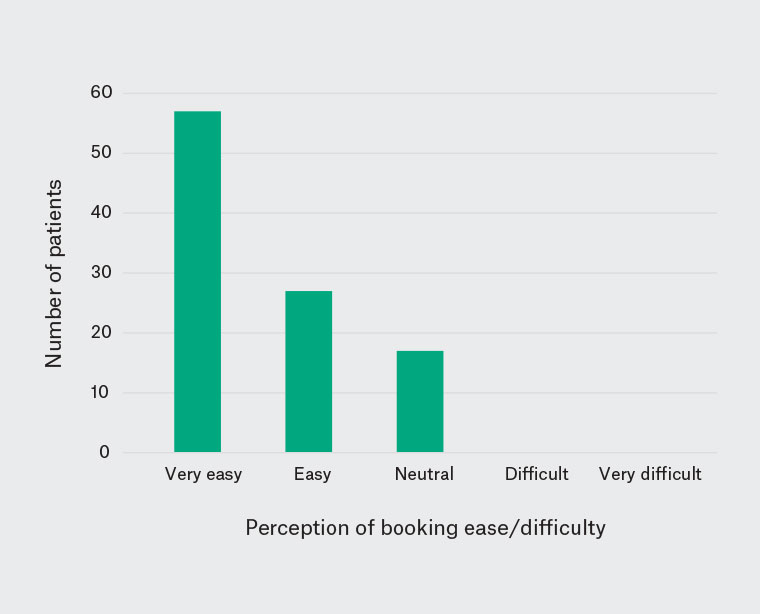

Although most found the booking process easy (Figure 3), many patients found it a difficult step to make the initial call to book in, indicating they felt nervous about making the call.

Figure 3. How patients rated the ease or difficulty of the initial booking process (ie How would you rate the initial booking process?).

I just had to pluck up the courage to do the initial phone call, the rest was easy and straight forward after that. The staff are very warm and welcoming, that got rid of a lot of my anxiety. (Participant 7, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

It was fine, having to call was the only thing that was making me nervous. (Participant 12, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Easy as. I was incredibly nervous and unsure when I first rang up, but the nurse I talked to was understanding and patient and got me booked ASAP. (Participant 28, aged 20 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

One patient identified that their sense of shame about being transgender was a barrier to making contact with the clinic:

From memory the call was daunting, I had a lot of shame about being trans and thought the nurses would be disgusted at someone booking. The way they were so helpful and positive made a lot of the initial stress go away. (Participant 11, aged 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

Misgendering and deadnaming

There was occasional misgendering by sexual health clinic reception or clinical staff (10%). One patient had a particularly difficult time when being seen by a visiting specialty team, as this necessitated a genital examination as part of their care for a particular medical condition.

Horrible. I am anxious coming here. Not great. I was misgendered many times as soon as they saw my genitals for dermatological issues. And I get anxious coming here. Some docs have changed their behaviour. The male doctors are the worst. They also don’t understand that our genitals cause some of us gender dysphoria and I feel so embarrassed just talking about it and being misgendered on top of that felt awful. (Participant 16, aged 35 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

It was noted that genital examination was a particularly difficult experience for this patient who found this exacerbated dysphoria and triggered misgendering:

Most docs and nurses will misgendered you if they see your genitals for any type of procedure. (Participant 16, aged 35 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

For another patient, being misgendered was disheartening, as they felt it was an indication that they were not ‘passing’:

It was at the very beginning of my transition and I didn’t pass but it was super disheartening at the time. (Participant 15, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

After being misgendered by a staff member, one patient welcomed an apology as a sign that the service was a safe environment.

I didn’t notice it, but another staff member apologised to me and said they’d talk to the person who did misgender me. Slip ups happen and intention is more important than always getting it right. Knowing that staff will correct others meant that I didn’t worry at all. (Participant 11, aged 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

Patients reported the importance of using their chosen name to make them feel comfortable accessing any medical care:

This is the only place that actually uses my real name and not my legal name when they can. It’s very hard to get medical care when you get misgendered and deadnamed. (Participant 12, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

It was acknowledged that misgendering and not using preferred names is a systemic problem in the healthcare system:

A lot of clinics are not accommodating for trans people. Even if they ask for preferred names and pronouns, they still use legal name and sex assigned at birth. (Participant 12, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Asking patients if pronouns had changed when they presented to reception and making sure it was on registration forms was noted by participants as a useful strategy to improve their experience.

Signage and resources

The majority of patients found the SHC reception staff welcoming, the waiting area welcoming, and clinic signage and resources gender inclusive (93%). Almost all said inclusive signage was important to them. The two patients who did not agree with these statements were neutral about them.

Many patients’ comments demonstrated the importance of clear indicators of acceptance of being TGDNB.

As a trans person, inclusivity is very important to me. (Participant 23, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Comments gave further explanation about why the gender-inclusive signage and resources were important. It provided confidence in the care they would receive:

It shows the clinic is aware of appropriate trans care. (Participant 6, aged 21 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

One patient commented on the importance of signage that is specifically transgender inclusive rather than just being focussed on cisgender gay men.

I don’t typically get to see trans inclusive signage, particularly surrounding healthcare. When people are referring to the LGBT healthcare they’re typically just referring to cis gay men. (Participant 15, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

The inclusive signage was identified as a simple but effective strategy to provide a sense of acceptance and safety that they often don’t find:

Yeah it’s just nice you know? The rest of the world isn’t very welcoming to be honest which is whatever, I get by but walking into a space that’s explicitly chill with trans and nb (non-binary) people takes some angst out of my day. (Participant 28, aged 20 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

I initially didn’t think I’d care, but making the place so accepting of trans people, in really an over-the-top way has always made me feel safe there, or not judged. (Participant 11, aged 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

Services received

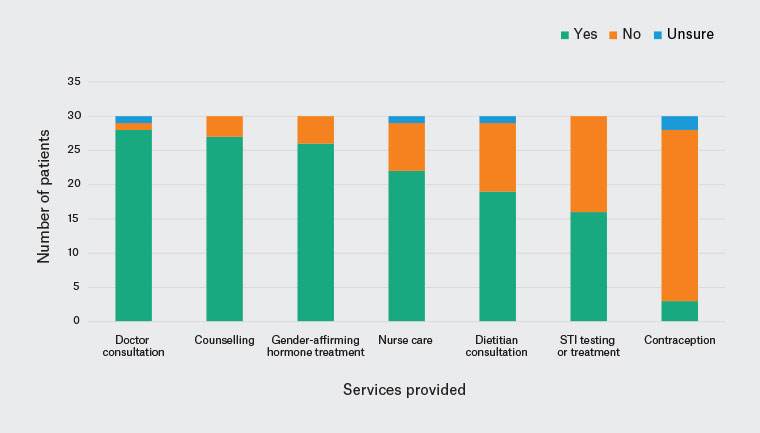

Patients reported that they accessed many of the services provided within the SHC (Figure 4). One patient was primarily seen by a consulting specialist team, not specifically the GAC service.

Figure 4. Services reported to have been received by patients within the gender-affirming care service.

STI, sexually transmissible infection.

Overall satisfaction

There was a high level of satisfaction with care received (64% very satisfied, 30% satisfied, 3% neutral, 3% unsatisfied, 0% very unsatisfied).

The example of one patient who was unsatisfied highlighted the need for consulting specialties to be trained in inclusive care. This was the patient who came to the clinic to access a different specialty:

All doctors and staff especially male doctors need basic training in gender care and using pronouns. They were gendering me as female until they saw my genitals. They then used he him pronouns. Worse they didn’t apologise. They just got embarrassed and tried to ignore it …

The (specialist) help was great but I feel a bit traumatised from my experience and humiliated and anxious cause I don’t know if they will misgender me. Looking forward to my bottom surgery so I no longer have to do this. (Participant 16, aged 35 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

Many of the patients commented on the importance of the service being available and the benefit of the support they received.

Love it. I will always be grateful for this place, legit saved my life. (Participant 28, aged 20 years, male, AFAB, he/his pronouns)

Patients identified that transitioning gender can be a challenging journey for them and support in navigating this can have profound benefits.

Absolutely this service has saved my life. I wouldn’t have coped if I had to find all these things independently during all the turmoil of transition. (Participant 11, aged 24 years, female, AMAB, she/her pronouns)

I feel very comfortable with everyone that I see and feel very supported in my journey. (Participant 15, aged 19 years, male, AFAB, he/him pronouns)

Discussion

There was a high level of satisfaction with the multidisciplinary GAC clinic and an acknowledgement by patients of the importance of this service. Being able to access multiple services in one supportive clinic was perceived as a definite benefit. This has been highlighted in other Australian research, which demonstrated the frustration experienced by these patients when accessing multiple health providers and services that they could have received in primary care.7 Many patients had difficulty finding out about the service and being referred to it, with very few finding out about the service from their GP. They experienced lack of knowledge from referring medical professionals, long and complicated waiting processes to be referred for care, including waiting to see psychologists, high costs of consultations and concern for confidentiality, even concern of being ‘outed’ by the family GP.

If more GPs provided GAC using an informed consent framework and support from specialist GAC services, TGDNB patients could avoid the frustrations they often experience accessing care. The informed consent model of care for adults accessing GAC is now recognised as best practice both in Australia and internationally.8,9,14–17 It is recognised that support and partnering from specialist services can facilitate TGDNB patients accessing care in general practice. NSW Health is developing a coordinated, statewide Specialist Trans and Gender Diverse Health Service (TGD Health Service) to provide gender-affirming healthcare for people aged <25 years. Although this service is limited to specialist transgender and gender-diverse health care, it aims to work closely with existing support services and primary care to provide holistic care for young people and their families and carers. In addition to the NSW-based youth TGD Health Service, NSW Health is working to ‘Establish an accessible, user-led pathway of care for people aged 25 years and above who are affirming their gender, including mental health and other wraparound supports’. GPs, through the Primary Health Networks, are listed as lead partners in this goal.18

Once they found out about the service, most patients in our study were able to receive a referral from a GP without difficulty. Those who had difficulty voiced concerns about GPs acting as ‘gatekeepers’ for hormone therapy. This issue of gatekeeping has been highlighted in research both in Australia and overseas.5,19,20 Even though they found the booking process easy, many patients found it daunting to make the initial call to make an appointment; having to ‘pluck up the courage’ and identifying a sense of shame. GPs can consider making this easier for anxious patients by being reassuring and facilitating a ‘warm referral’ process.

Patients appreciated the effort the service went to ensuring correct pronouns and names were used and identified this as a facilitator to receiving healthcare generally. GPs could add pronoun and preferred name fields to registration forms, as the GAC service does, as an indicator of inclusiveness and validation. Simple, inclusive, transgender signage, such as a small transgender flag at reception, was also noted as being important. Rather than being perceived as tokenistic, patients appreciated these simple measures and said they made them feel safe and validated, and gave them confidence to seek care. There are a range of resources that can assist GPs and other healthcare providers to offer inclusive registration and other patient data collection resources. In 2020, The Australian Bureau of Statistics produced a new standard to guide the collection and use of sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation variables.21 TGDNB organisations and advocacy groups are available to consult and provide expert advice and guidance on using inclusive language. For a list of these groups, refer to Table 2.

The GAC service signage of bathrooms is non-binary, a simple but important inclusive measure GPs can adopt that is supported by other research.22

Misgendering was not common in the GAC service, but some patients commented on this and their experience of misgendering by other health professionals outside the service. They commented on the effect of this on accessing healthcare. This supports what is discussed in the literature3,6,7,23 with regard to the effect of misgendering and deadnaming as a barrier to care and the health disparity experienced by TGDNB people. One patient commented on the difficulties of having a genital examination; not only can this heighten dysphoria, it is also a trigger for misgendering by the clinician. It is understandable that genital examinations and other gender-specific medical practices, such as breast/chest examinations and the provision of contraception, are times in a medical consultation that misgendering is more likely to occur. There is good research to support the importance of not gendering healthcare services (eg ‘Women’s health clinic’ as opposed to ‘Reproductive and sexual health clinic’) and of using inclusive language when naming body parts.24,25 However, this trigger for accidental misgendering does not seem to have been reported in previous research. Health professionals should be particularly aware of this, and especially mindful of chosen names and pronouns during genital, breast/chest examinations and other ‘gendered’ healthcare services, such as contraception provision. Patients noted that a simple apology can be very effective when misgendering occurs, and staff support of correct pronouns being used was appreciated and gave them a sense of safety.

There are useful references and resources that discuss simple strategies for GPs to provide inclusive healthcare to TGBNB9,26,27 to facilitate engagement in healthcare and access to the care they need (Table 2).

| Table 2. Useful transgender, gender-diverse and non-binary resources for clinicians and patients |

| Organisation |

Type of resource |

Website |

| For clinicians |

| AusPATH |

E-learning module: trans primary care |

https://auspath.org.au/2021/06/13/e-learning-module-trans-incl-gender-diverse-and-non-binary-primary-care |

| AusPATH |

AusPATH: Australian Informed Consent Standards of Care for Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy |

https://auspath.org.au/2022/03/31/auspath-australian-informed-consent-standards-of-care-for-gender-affirming-hormone-therapy |

| LGBTIQ+ Health Australia |

Workforce resources |

www.lgbtiqhealth.org.au/workforceresourcesw |

| Queensland Council for LGBTI Health |

Practice guidelines |

www.qc.org.au |

| Rainbow Health Australia |

Research, projects and resources |

https://rainbowhealthaustralia.org.au |

| Trans Health SA |

Research and resources |

https://new.transhealthsa.com |

| Royal Melbourne Hospital and Zoe Belle Gender Collective |

Care guide for healthcare professionals |

www.thermh.org.au/files/documents/Corporate/transgender-gender-diverse-inclusive-care-guide-health-care-professionals.pdf |

| TransHub |

Downloads for clinicians

Information for clinicians |

www.transhub.org.au/clinicians |

| For patients |

| ACON |

Resources, programs, services and referrals |

www.acon.org.au/who-we-are-here-for/tgd-people |

| A Gender Agenda |

Support for intersex, transgender and gender-diverse people in the ACT |

https://genderrights.org.au |

| Queensland Council for LGBTI Health |

Patient resources and support |

www.qc.org.au |

| Q Life |

Telephone and webchat support service |

www.qlife.org.au/get-help |

| The Gender Centre |

Services and support for the transgender and gender-diverse community |

https://gendercentre.org.au |

| TransFolk of WA |

Services and support for the transgender and gender-diverse community |

www.transfolkofwa.org |

| Trans Health SA |

Services and support for the transgender and gender-diverse community |

https://new.transhealthsa.com |

| Transhub |

Transgender vitality tool kit |

www.transhub.org.au/health |

| Twenty 10 |

Twenty 10 supports people across New South Wales who may be LGBTIQA+ |

https://twenty10.org.au |

| ACT, Australian Capital Territory; AusPATH, The Australian Professional Association for Trans Health; LGBTIQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer + others not explicitly mentioned, such as pansexual, agender and asexual; SA, South Australia. |

Limitations

Although this is a small questionnaire in terms of numbers of patients (30), it had a good participation rate (71%) and provided a good representation of patients who accessed GAC.

There are inherent biases with questionnaires generally, which we tried to minimise with our questionnaire design. Another limitation of this research is that it only captures one time point when patients might have been at different stages of their care. However, this should not affect the rich data from the free-text comments about access and referral issues discussed in this paper. The participants were clinic patients who had elected to remain in the care of the clinic, so might be biased towards indicating a level of satisfaction with the clinic. The clinic only sees patients aged >18 years, so this research does not report on the experience of those aged <18 years who might face different issues in accessing care.

Conclusion

With increasing services being provided for GAC of TGDNB patients, it is important for all GPs to ensure they have the necessary knowledge and simple strategies to be able to help these patients feel comfortable in seeking healthcare and referral to services if not providing hormone therapy themselves. With increased knowledge and comfort, GPs can also play an important role in partnering with specialist services to provide this care.