Medicinal cannabis (MC) was legalised in Australia in 2016 following a parliament enquiry, which led to an exponential increase in prescribing.1 However, until widespread MC drug registration occurs, prescribers must apply to the Special Access Scheme (SAS-B) or become authorised prescribers (AP) through the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).1 The SAS-B requires healthcare practitioners to apply for each patient to be able to access each category of MC products.1–3 The AP scheme allows healthcare practitioners to prescribe MC products without the need to seek approval for individual patients. Although this represents a major streamlining of the prescription process, the AP scheme is primarily geared towards high-frequency prescribers due to considerable administrative requirements.1–3 This unique situation has led to challenges for both general practitioners (GPs) prescribing and patients seeking access.4 Using Levesque’s concept framework of access to healthcare, this scoping review examined the shifting barriers and enablers to accessing GP-prescribed MC in Australia.

Methods

Design

This review identified the scope of the scientific and grey literature pertaining to barriers and enablers to accessing legal MC through GPs within Australia. Access to MC has rapidly developed since legalisation in 2016.5–7 Accordingly, a scoping review methodology was selected to address the broad topic8 and include a wide range of literature quality.9 This scoping review followed the five-stage framework described by Arksey and O’Malley.8

Inclusion criteria and literature search

For inclusion, literature had to be written in English, published from 2016 onwards, include a key theme of barriers or enablers to accessing MC in the Australian GP setting and constitute primary research (if scientific).

All researchers identified search terms relevant to each concept, then mapped medical subject headings (MeSH). Given the recent nature of this field of research (since 2016), databases were searched extensively, ensuring a low false-negative rate. An experienced research librarian verified the validity of the terms for the scientific and grey literature searches, summarised in Tables 1 and 2. The scientific literature search was conducted in July 2023 by SM across four databases: PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL and Embase. The grey literature search was conducted by SM in July 2023 using an advanced Google search.

| Table 1. Search terms used in PubMed |

| |

Medicinal cannabis |

Barriers, enablers |

Australians |

General practitioner |

| Text word |

‘medicinal cannabis’

‘medical cannabis’

‘medicinal marijuana’

‘medical marijuana’

‘cannabis based medicine’

‘cannabis-based medicine’

‘cannabis therap*’

‘cannabis extract*’

‘cannabi*’

|

opportunit*

barrier*

challeng*

obstacle*

limitation*

constrain*

experience*

enable*

facilitat*

impact*

adapt*

effect*

hinder*

encourage*

discourage*

impede*

uptake

attitude*

perspective*

knowledge

perceive*

perception* |

Australia*

‘Australian population’

‘Australian market’

‘New South Wales’

‘Queensland’

‘South Australia’

‘Victoria’

‘Northern Territory’

‘Western Australia’

‘Tasmania’

‘Canberra’ |

Doctor*

General practi*

‘Authorised prescriber*’

‘GP’

‘general physician’

|

| MeSH headings |

‘Cannabis’ ‘Cannabinoids’

‘Medical marijuana’ |

|

|

‘General practitioners’ |

| MeSH, medical subject headings. |

| Table 2. Search strategy used in Google |

|

| Search terms |

Site types |

Legal AND medicinal AND cannabis AND access AND Australia

AND general practitioner |

site:gov.au |

| site:com.au |

| site:org.au |

Data extraction

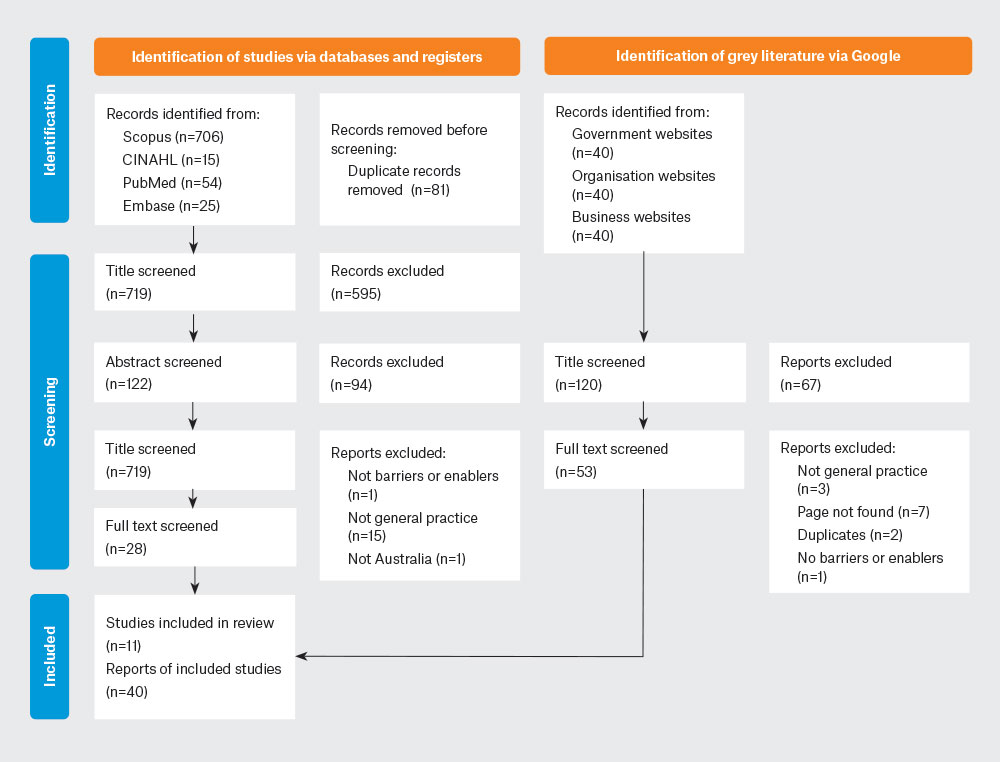

Data were extracted from PubMed (n=54), Scopus (n=706), CINAHL (n=15) and Embase (n=25). Three researchers conducted screening (SM, SJ and AT). At each stage, two researchers conducted screening and a third reviewed and decided on any conflicts. Screening removed 787 papers, leaving 11 papers for inclusion (Figure 1). Data were extracted from the first four pages of Google, for three searches (n=120) (Figure 1). Initial and full-text screening removed 80 websites, leaving 40 for analysis. Both screens were conducted independently by SM and AT, and conflicts were reviewed and decided on by SJ.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Adapted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutros I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372, doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. Visit www.prisma-statement.org for more information.

Data analysis

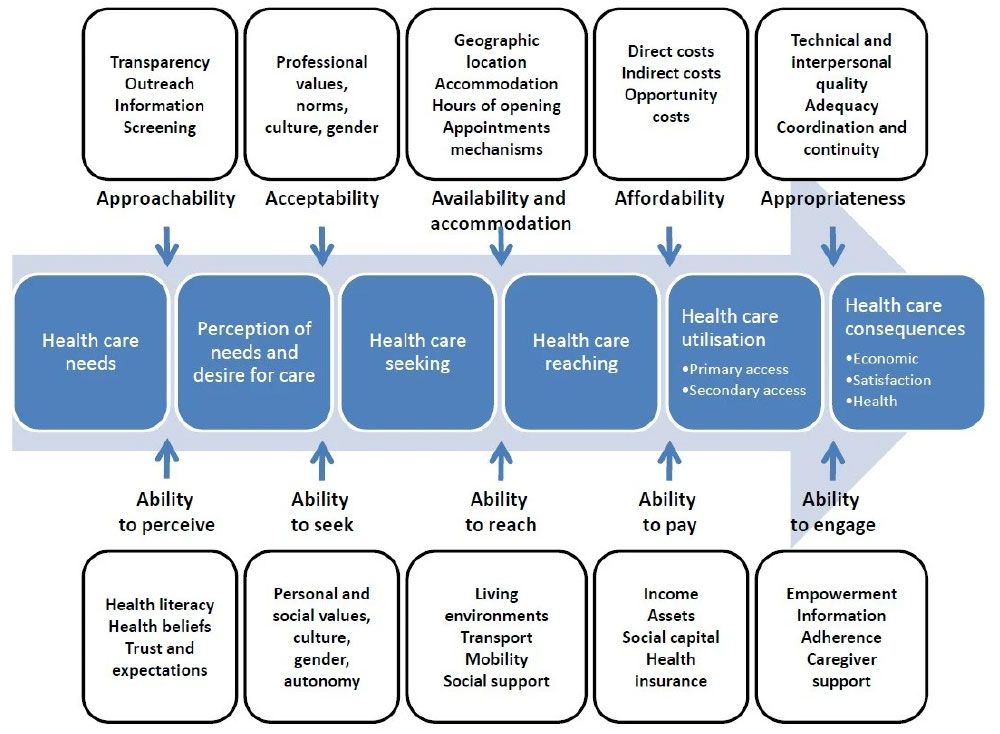

Data were analysed using the ‘Conceptual framework of access to healthcare’ framework (Figure 2).10 Thematic analysis was completed by SM and SJ, and findings were sorted into dimensions of healthcare access. Commonly used dimensions represented themes that characterised the review’s key findings. Themes were reviewed by the senior researcher (AW) to ensure a high quality of analysis.

Figure 2. Levesque’s framework, ‘Concept framework of access to healthcare’.10

The top row represents ‘dimensions of accessibility’, and the bottom row represents the ‘abilities of the patient’. Collectively, these generate access to healthcare.

Reproduced from Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12(1), doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18.

Results

Eleven scientific research studies were analysed (Table 3). Of the 11 included papers, four were perspectives from healthcare providers4,11–13 and five were perspectives from patients.6,7,14–16 The remaining papers included a thorough examination of all stakeholders involved in accessing MC5 and a commentary.1 Forty-four grey literature webpages were analysed. Of the 40 retained webpages, 24 were business pages,17–40 13 were government pages,2,41–52 two were organisation pages53,54 and one was a university page.55

| Table 3. Summary of scientific studies |

| Article |

Title |

Population |

Study design |

| Bawa et al 20224 |

Knowledge, experiences, and attitudes of Australian general practitioners towards medicinal cannabis: A 2021-2022 survey |

Australian registered GPs or general practice registrars who were attending online, multi-topic, educational HealthEd (CME) events |

Quantitative, non-comparative, cross-sectional survey |

Chandiok

et al 202111 |

Cannabis and its therapeutic value in the ageing population: Attitudes of health-care providers |

Rural NSW healthcare providers’ attitudes towards cannabis for older (aged >65 years) patients |

Qualitative, grounded theory |

| Erku et al 20225 |

From growers to patients: Multi-stakeholder views on the use of, and access to medicinal cannabis in Australia |

Submissions to a parliamentary enquiry into barriers and enablers to cannabis access, 2019. This study included submissions from patients, family members of patients, government bodies, non-governmental organisations, medicinal cannabis and pharmaceutical industries, individual health professionals, academics and research centres |

Qualitative, grounded theory |

| Hallinan, Gunn and Bonomo 202112 |

Implementation of medicinal cannabis in Australia: Innovation or upheaval? Perspectives from physicians as key informants, a qualitative analysis |

21 prescribing and non-prescribing key informants working in neurology, rheumatology, oncology, pain medicine, psychiatry, public health and general practice |

A thematic qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews |

| Hallinan and Bonomo 20221 |

The rise and rise of medicinal cannabis, What now? Medicinal cannabis prescribing in Australia 2017–2022 |

N/A |

Commentary |

Karanges

et al 201813 |

Knowledge and attitudes of Australian general practitioners towards medicinal cannabis: A cross-sectional survey |

Australian registered GPs or general practice registrars who were attending in-person, multi-topic, educational HealthEd (CME) events in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth |

Quantitative, non-comparative, cross-sectional survey |

| Lintzeris et al 20206 |

Medical cannabis use in the Australian community following introduction of legal access: The 2018–2019 Online Cross-Sectional Cannabis as Medicine Survey |

Aged >18 years, used cannabis for a self-identified reason in the past year, Australian resident |

Quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional survey |

| Lintzeris et al 20227 |

Medical cannabis use in Australia: Consumer experiences from the online cannabis as a medicine survey 2020 |

Aged >18 years, used cannabis for a self-identified reason in the past year, Australian resident |

Quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional survey |

| Sinclair et al 202215 |

“Should I Inhale?” –Perceptions, barriers, and drivers for medicinal cannabis use amongst Australian women with primary dysmenorrhoea: Qualitative study |

Women, aged >18 years, experienced moderate or greater period pain for at least two-thirds of their most recent periods. ‘Self-prescribed’ medicinal cannabis |

Qualitative, descriptive |

| Sinclair et al 202214 |

Cannabis use for endometriosis: Clinical and legal challenges in Australia and New Zealand |

Diagnosed endometriosis patients, aged 18–55 years, used cannabis in past 3 months for managing endometriosis symptoms |

Quantitative, non-comparative, cross-sectional survey |

| Wilson and Davis 202116 |

Attitudes of cancer patients to medicinal cannabis use: A qualitative study |

Cancer diagnosis, in one regional community (not stated) |

Qualitative, grounded theory |

| CME, continuing medical education; GP, general practitioner; N/A, not applicable. |

Dimensions of accessibility

These results outline the ability of GPs to generate access within the healthcare system. They pertain to the top row of the Levesque’s framework (Figure 2), which represents the ‘dimensions of accessibility’.10

Approachability

Limited GP knowledge of MC formed an approachability barrier for patients, as many GPs felt uncomfortable discussing MC with patients.4,12,13 Patients who perceived that GPs lacked knowledge felt frustrated with the process14,16 and, consequently, sometimes forewent legal access.6,7,14,15 Surveyed GPs felt they had inadequate knowledge about MC,4,5,11–13 particularly regarding regulations, the SAS and available products. Knowledge deficits resulted in GPs feeling disempowered when discussing or prescribing MC.17,55

Overall, GP knowledge of MC contained inaccuracies.4,11,13 Many doubted its safety, believing product labelling could be unreliable in concentration or dosage,1,11 despite stringent TGA monitoring and regulations. Limited understanding of cannabinoid differences was also evident, as there were concerns over cannabidiol and driving impairment or risk of addiction, which have both been disproven.4 Although web-based government and professional organisation resources exist,2,17,20,41–46,53,55 most GPs felt it was burdensome to self-educate12 due to time scarcity.11 Many GPs voiced a desire for thorough MC training.4,11–13

More recently, patients have felt MC is becoming easier to discuss in consultations, and GPs felt that there was an uptake in MC prescribing.11,12,16 This was reflected in survey data, with a rise in GPs prescribing MC from 2.7% to 37.7% between 2018 and 2020.6,7 Furthermore, more patients now discussed MC with their GPs.6,7 Additionally, GPs reported higher confidence discussing MC4,13,16 when experienced in navigating the prescribing process.12

Acceptability

Acceptability was a barrier for both patients and GPs.4,5,11–14 MC prescription was polarising, where prescribers and non-prescribers both described facing stigmatisation in different areas.5,11,14 Some GPs worried cannabis legislation was a political response to patient demand,13 allowing access to ‘drug-seeking patients’,4 and dependence has remained a concern over time.4,5,11–13,21 Ironically, fear of being perceived as drug-seeking led patients to source MC illegally and not disclose use to their GPs.7,14,15 Despite a reported decline in stigma,11 the Cannabis as Medicine Survey 2020 (CAMS-20) survey showed finding medical practitioners willing to prescribe MC was still a barrier to access for many Australians.7

Safety concerns and unreliable monitoring of MC adverse events hindered GPs from prescribing.4,5,12,13 A robust pharmacovigilance system, specifically for MC products, was requested, as the current system was viewed as inadequate.5,12

Availability and accommodation

Geographical location played a significant role in access, with rural patients at a disadvantage compared to metropolitan ones.5 Rural patients chose from a smaller pool of GPs, which compounded any perceived issues with GP bias against MC.5,14,15 Certain states and locations had far better access to MC,5,12,14 described as a ‘postcode lottery’, which sometimes led to patients needing to relocate, becoming ‘cannabis refugees’,5 travel long distances or forfeit their medication altogether.1,5,14 One paper noted there was an over-representation of GPs prescribing MC in Queensland.4 Contrastingly, the TGA received lower prescription numbers per capita for Tasmania compared with other states, likely due to Tasmania opting out of the national approval portal for MC prescriptions.13

Affordability

The cost of MC, including travel, consult and prescription costs, was a barrier for both patients and GPs.4–7,12–14 Cost as a barrier has remained largely unchanged since the senate enquiry into MC access in 2019.5 Some GPs considered not prescribing MC due to the financial burden on patients.13 Patients found the cost of appointments at specialised clinics also created a barrier to access.5,7,12,14

Appropriateness

The appropriateness of MC prescription was a concern for GPs due to the lengthy prescription process,4,5,11,12,16 potential harm4,11–14 and the paucity of high-quality evidence for safety and efficacy.5,11–13 Additionally, perceived appropriateness might have been impacted by the TGA cannabis prescribing guidelines, which, although stating how to prescribe MC, do not officially recommend its prescription.2,45,46

Abilities of the patient

These results outline the ability of patients to find access to legal MC within the healthcare system. They pertain to the bottom row of the Levesque’s framework (Figure 2), which represents the ‘abilities of the patient’.10

Ability to perceive

Ability to perceive was a key determinant in the prescription process, where patients needed to trust their GPs sufficiently to discuss their interest in MC. Trust concerns were particularly prevalent among the rural population with limited GP options.14,15 Concerns included legal consequences and being labelled a drug user, leading some patients to withhold their MC use from GPs.6,7,14–16 Despite plentiful online resources,23–26,47–51,54 some patients lacked health literacy surrounding MC.7 Some patients assumed their doctors would be unwilling to prescribe MC.6,7,15 These findings indicate that although the Australian population is becoming more comfortable with discussing MC with GPs, some cohorts such as the rural population still face significant barriers.6,7,14,15

Ability to seek

The ability to seek had both barriers and enablers to access. Social stigma, from the community and healthcare professionals, was a considerable barrier.5,11,14,15,27 However, some experienced an ‘unprecedented’ pro-MC social influence through families of those with chronic conditions, celebrities and advocacy groups.12 Recommendations from friends and positive comments from social influencers contributed to reducing stigma among family and friends.12,14,15 The Australian MC industry has been playing a substantial role online in destigmatising patients seeking access, through blogs presenting a blend of health information and links for patients to access cannabis specialist doctors30–35 or cannabis-friendly GPs.36–38 These findings indicate patients might encounter both barriers and enablers; some faced stigma socially and in the medical system, whereas others encountered pro-MC influencers and healthcare practitioners who were MC friendly.

Ability to reach

Disparities in MC access were observed between states, and in urban versus rural areas.5,14 Rural residents faced difficulties in reaching MC medication, exacerbated by challenging drug-driving policies.5,14 The emergence of telehealth cannabis clinics that are accessible online30–35 and the availability of bulk-billing clinics and pharmacies offering express shipping39 have helped bridge the rural–urban gap.

Ability to pay

The cost of MC was a common barrier to legal MC access,5–7,16 especially for patients with chronic conditions who relied on pensions and could not engage in full-time employment.5,16 Affordability issues sometimes turned patients towards illegal cannabis.6,7

Ability to engage

Engaging in the MC access process tended to be complex and lengthy.6,7 Patients and healthcare providers reported that legal access to MC was too challenging,5–7,15 and some patients were unaware of legal channels.6,15 These findings indicate that it has been difficult to engage with MC access from start to finish. The advent of telehealth cannabis clinics30–39 and streamlining of the TGA application process2,13 might lessen barriers to patient engagement.

Discussion

Accessing MC in Australia is challenging for both GPs and patients; the prescribing process, lack of training and cost all represent barriers. Not all barriers can be improved; for example, reduction in the cost of accessing MC is unlikely until strong evidence allows a number of products to gain registration for common conditions. However, the significant increase in MC prescribing in the past five years1 indicated a reduction in barriers. Incorporating MC education into the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ curriculum could further reduce access barriers, as GPs have demonstrated an appetite for learning in the current prescribing environment.4,11–13

Some GPs were reluctant to prescribe MC, as they saw MC legalisation as the result of patient lobbying rather than clear clinical evidence.5,12 This, therefore, caused some GPs to have concerns regarding safety and efficacy.12 These concerns arise from GP misconceptions,4,14 a paucity of high-quality clinical evidence5,11–13 and guidance from the TGA, which offers education on MC but does not endorse its prescription.2,45,46

Additionally, further reluctance to prescribe stemmed from knowledge gaps.17,55 However, chronic time scarcity affects the ability of GPs to regularly educate themselves on the latest evidence. Time constraints on GPs who want to prescribe MC are compounded by the complex and time-consuming MC prescription process.11,17,55 Although the TGA has implemented the AP process to alleviate the need for SAS-B applications, this might not be perceived to be a viable option for GPs due to the application and reporting requirements.3 This also can cause a lengthy process for patients,4,22,40 influencing the appropriateness of MC as a therapy. Creation of succinct and topical short courses for GP professional development should be considered.

Many patients still experienced stigma from family, friends and healthcare professionals, which sometimes led them to forgo seeking MC therapy.5,11,14,15,27 However, the stigma associated with MC use was overall lessening, thereby influencing its acceptability among patients and healthcare providers. This shift might be attributed to broader societal changes5,11 and the private MC industry’s efforts in online messaging and information sharing.18,28–31,33–35

Geographical access barriers in healthcare have also improved following the increased use of telehealth consults during the COVID-19 pandemic.56 This has led to a reduction in demographic disparities,5 particularly in rural and remote areas of Australia.30,31,33–35

Affordability barriers drive inequality, due to the costly process of accessing MC.5,16 Initial and review appointments with MC specialists involve substantial out-of-pocket expenses.13 Along with the high MC product cost, this disproportionately affects lower socioeconomic populations,5,16 leaving some GPs reluctant to prescribe MC due to the ongoing cost.5 Given that MC was predominantly accessed by the SAS scheme,2,20 some of the cost incurred is dependent upon research supporting widespread product registration and subsequent cost–benefit analyses to allow for subsidy applications. Until then, enhancing GPs’ understanding of processes and products could help limit the cost of MC consults.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that, although some geographical and stigma barriers to accessing MC through GPs have improved, significant access barriers persist in Australia. The MC prescription process creates inequities for patients unable to afford the significant costs. Many of the barriers can be partially addressed by supporting GPs to access MC-focused professional development, including on the prescribing process, to enable them to consider MC as a viable treatment option for suitable patients.