There is very little research on the experience of sexual assault victim-survivors who present for a health response.1 The available research is often from a proxy, such as interviews with counsellors or advocates, and not directly from the perspective of the victim-survivor themselves. There is some evidence that when the forensic examination is provided as an integrated health response, including psychosocial support from a professional counsellor and forensically trained doctors or nurses, it can be ‘therapeutic’ rather than re-traumatising.1–4

The New South Wales state health system supports timely access to psychosocial, medical and forensic care of recent sexual assault victims by providing crisis 24-hour services in every local health district (LHD). This ‘health’ response uses a framework of trauma-informed and patient-focused principles supported by statewide policy and practical training through the Ministry of Health and the Education Centre Against Violence.5 In the Northern Sydney LHD (NSLHD), the Sexual Assault Service (SAS) sits within the Prevention and Response to Violence Abuse and Neglect (PARVAN) department.

Patients who present to hospital or other NSLHD services after a recent sexual assault (usually within seven days) are offered an immediate response. Patients are triaged by the emergency department (ED) staff and then seen by the SAS. This consultation is provided as a team approach, with a counsellor working alongside a doctor or nurse, seeing the patient together. The on-call staff roster includes approximately 8–10 counsellors and 8–10 medical staff (doctors and sexual assault nurse examiners). There is a mix of staff who work as part of the daytime staff providing weekday and after-hours responses and those who only work after hours (ie they have other daytime roles in areas such as mental health, hospital social work, general practice or sexual and reproductive health). This occurs within the designated forensic suite in the Royal North Shore Hospital (RNSH) ED.

Regardless of whether patients have reported the sexual assault to police, a forensic examination is offered to all patients who attend within the forensic time frame (depending on the nature of the assault, this could be 12, 24 or 48 hours, or up to five or seven days). Forensic examination involves the recording of a history of the assault, documentation of any injuries and collection of biological specimens, as appropriate. This information is recorded within the standardised protocol (the medical forensic examination record [MFER] and samples collected using a sexual assault investigation kit [SAIK]).

Medical care encompasses assessment of sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk, prophylaxis when appropriate and follow-up testing; provision of emergency contraception, when indicated; and injury management. Serious injuries are managed by the ED. Psychosocial care is provided as an immediate intervention, including responding to immediate impacts, safety assessment, psychoeducation and information, and resource provision with the facilitation of ongoing counselling. The counsellor will also undertake referral and liaison with service providers and family/support people.

Patients aged ≥16 years have the option to release the MFER and SAIK to police or to temporarily store them within the hospital for up to three months. During this time, they can decide to release the samples and accompanying information to police for forensic processing. After three months, samples not released are discarded but documentation is kept. For patients aged ≤15 years, all forensic information is released to police to comply with child protection legislation.

The aim of this research was to explore the experience of victim-survivors who present to our sexual assault service. We were particularly interested in their experience of the medical forensic examination. By adapting a validated patient questionnaire,3 we aimed to obtain immediate feedback about the sexual assault service, including their experience of the examination, from the perspective of the patients themselves.

Methods

This research study used a 24 question, paper questionnaire including simple tick-box options, Likert scales (using sad to smiley faces for ‘poor’, ‘average’, ‘good’, ‘great’) and free-text options (Figure 1). The questionnaire was adapted from the client feedback form developed by Saint Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre in Manchester, UK.3

The questionnaire was first implemented in March 2020 and is ongoing. Analysis is based on data from four years to March 2024. Patients were offered the questionnaire (with an information sheet and sealable envelope) at the end of the integrated response after a recent sexual assault, while discharge papers were being prepared. The responses were entered into a password-protected Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A descriptive analysis was performed on the data.

This project was approval by the NSLHD Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/ETH01766).

Figure 1. Example of the survey questions used for this study.

Adapted from Majeed-Ariss R, White C, Saint Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre, Manchester. Feedback questionnaire. J Forensic Leg Med 2019;66:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.06.001, with permission from Saint Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre, Manchester.3

Results

Participation rates

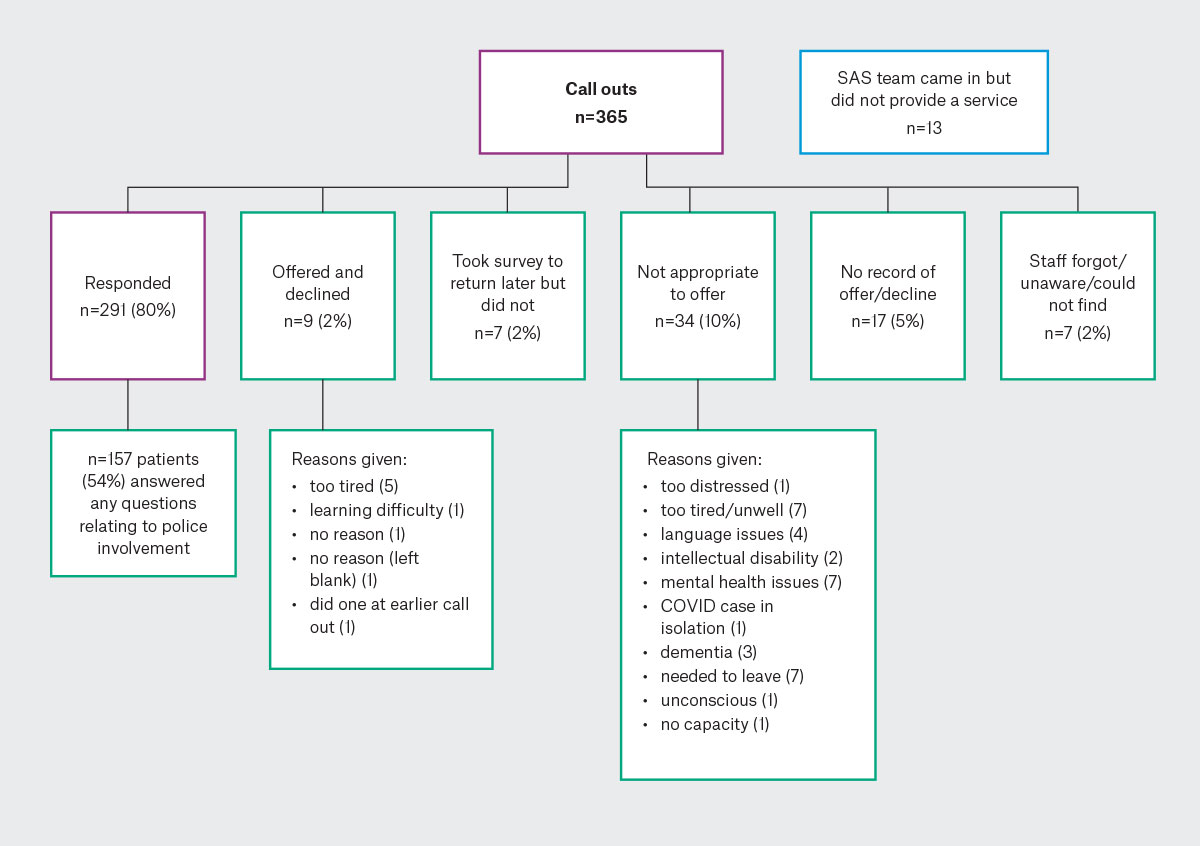

There was high participation with an 80% response rate (291 of 365). It was deemed not appropriate to offer the survey to 9% (34/365) of patients (refer to Figure 2 for reasons); staff omitted to offer it in error in 2% (7/365), 2% (9/365) declined, 2% (7/365) offered to return it but did not, and there is no record of whether it was offered for 5% (17/365) of patients. Most patients added free-text comments.

Over one-third (35%) of patients (103 of 291) agreed to be contacted to participate in future research.

Figure 2. Survey participation for patients attending the SAS for a crisis response.

Figure 2. Survey participation for patients attending the SAS for a crisis response.

Numbers represent the number of respondents. Reasons without an affiliated number are n=1. SAS, sexual assault service.

Referral source

Patients were asked how they heard about the service. The main reported referral source to the service was police (37%, 106/291 police alone, 6%, 16/291 police plus another source [eg RNSH ED], a 1800 crisis number or a friend). The next most common referral source was the RNSH ED (16%, 46/291); this included those speaking with a SAS counsellor first and those presenting directly to the ED. Other referrers were other EDs in the LHD (12%, 36/291), a crisis phone number (8%, 22/291), friends and family (7%, 21/291), other (not specified) (7%, 19/291), via an internet search (3%, 8/291) and general practitioners (4%, 12/291) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Referral sources for patients attending the sexual assault service for a crisis response.

ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; RNSH, Royal North Shore Hospital.

Overall care provided by the sexual assault service

When asked about the overall care and support provided by the sexual assault service, of the 288 who answered, 93% (269) rated it as ‘great’, 6% (18) ‘good’, <1% (1) ‘average’ and no-one rated it as poor.

When patients were asked if a friend was in a similar situation to yours, would they advise them to come to this service, of the 284 who answered, 98% (279) stated that they would advise a friend to engage with the service. As one respondent commented, ‘They made a hard day feel a little easier’.

Only one patient said they would not recommend the service to a friend, although she rated her overall care and support from the service as ‘good’ and gave little further information and missed several questions. Four said they were ‘not sure’ if they would advise a friend in a similar situation to attend the service. Two of these four said the overall care and support was ‘great’; one said ‘good’ and one said ‘average’. This particular patient commented that the examination was ‘reassuring’, medical care was ‘excellent’ (she ticked ‘great’ and created a new category to tick) but had been unnecessarily delayed in being seen by the service due to incorrect advice from police about when to present; ‘The police told us to wait 2.5 hours and attend at 6 am when everything would be ready. They didn’t make the call and we waited for 2 hours. Very poor management of a vulnerable person’; this highlighted the importance of good communication prior to patient presentation.

There was generally positive feedback about the police response (when police were involved) and the way the patients were managed in the ED before seeing the sexual assault team.

Emergency department reception and triage

When asked to rate how they were treated in the service’s ED on arrival, of the 283 patients who answered, 82% (232) said ‘great’, 12% (35) ‘good’, 5% (15) ‘average’ and <1% (2) ‘poor’.

Positive written comments by patients addressed feeling comfortable and safe, and staff professionalism and discretion:

Very friendly, understanding and I felt very comfortable. (Patient 30)

Knew what to do with me straight away. (Patient 41)

Very professional and discreet. Maybe use the side room for triage (for privacy). (Patient 59)

Made me feel very safe. (Patient 42)

I was treated with absolute privacy, so helpful. I felt so safe and (staff were) polite and professional. (Patient 158)

Separate room very respectful. (Patient 54)

Some patients who provided an average or poor rating described feeling uncomfortable, scared and exposed. They commented that they found it confronting making it known that they were presenting to see the sexual assault service.

I felt very uncomfortable, anxious and scared waiting in the ED waiting room. (Patient 37)

The receptionist said she couldn’t hear me, had no idea why I was here and made me say very loudly that I was here because of a possible sexual assault. (Patient 165)

No privacy asking me why I was there in a room full of people. (Patient 230)

Felt a bit stand offish at reception but was really nice and softened when I said I’d called the Sexual Assault Service. (Patient 17)

Everything was of a high level of professional - minus me not knowing what to say when I got here. (Patient 28)

Being expected by the triage nurses or having a code phrase (the forensic suite name is the ‘Jacaranda Suite’) was seen to be beneficial.

Ability to say ‘Jacaranda Suite’ so valuable in busy ED without privacy. Not as confronting. (Patient 219)

Police involvement

Regarding police involvement, when asked if the police officer/s (or detectives) fully explained why they were being asked to attend the service, of the 117 who responded, 80% (94) said ‘Yes’, 13% (15) responded ‘Not sure’ and 7% (8) of the patients said ‘No’.

When asked if the police officer/s (or detectives) told them that they had a choice about attending the SAS, of the 149 patients who responded, 75% (111) responded ‘Yes’, 12% (18) said they were ‘Not sure’ and 13% (20) said ‘No’ they were not told they had a choice.

The questionnaire asked the patients to provide any other information about how the police treated them when they were in their care. The comments were mostly positive and indicated that they felt supported and well informed by the police who were professional, kind and caring.

Don’t feel pressured into anything. (Patient 12)

Explained their role and the services (with professionalism and care). (Patient 26)

The police were supportive, informed and kind. (Patient 15)

I felt safe. (Patient 32)

Just the best, nicest, wise, honest, trusting, incredible men. (Patient 93)

Kind, thoughtful, understanding. (Patient 12)

They reassured me and constantly reminded me that I had full choice over what I do. (Patient 144)

However, some patients felt pressured by police and that the priorities of the investigation were more important than the victim–survivor:

I was told if I did not get the examination, the investigation would not go forward. (Patient 58)

They seemed focused on the crime rather than me, but ok. (Patient 128)

The officers on the scene were very rude and pushy. They made me feel like I was getting punished. (Patient 128)

Counselling aspect

When patients were asked to rate the sensitivity shown by the SAS counsellor, of the 281 who answered this question, 94% (265) answered ‘great’, 5% (15) ‘good’, <1% (1) ‘average’ and no one rated it as ‘poor’.

When asked for a free-text response to the questions about the counselling aspect of the service, the comments were all positive, with the main themes being that the counsellors were kind, caring, understanding, respectful, empathetic and that they made the patients feel safe, validated and listened to.

With respect, understanding and kindness. I felt that she listened and believed me. (Patient 67)

I am so grateful that I was treated with such dignity after my experience. (Patient 158)

Thank you for your exceptional service, it’s helped me deal with a traumatic situation. (Patient 13)

Made me feel myself again and not feel worthless. (Patient 12)

Medical-forensic aspect

When patients were asked to rate the sensitivity shown by the doctor/nurse, of the 284 who answered this question, 96% (272) answered ‘great’, 3.5% (10) ‘good’, <1% (2) ‘average’ and no one rated it as ‘poor’.

When asked for a free-text response to the questions about the medical/nursing service, the comments were overwhelmingly positive, with themes of respect, understanding, kindness, professionalism, gentleness, explanation, with an emphasis on informed consent.

She treated me very well and made sure I was ok and informed me of what was happening. (Patient 35)

(Treated) very professionally and also with great concentration to me not being too naked. (Patient 62)

Very gentle and kind. Walked me through it all. Was very considerate of me and my emotions. (Patient 19)

With care, she made it very clear I could ask to stop and she made me feel safe. (Patient 67)

The examination

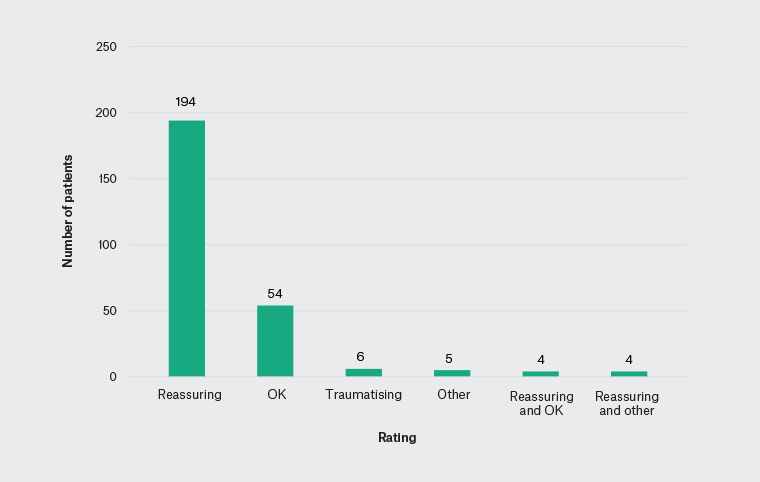

Patients were asked to rate the impact of the examination with the options of ‘reassuring’, ‘OK’, ‘traumatising’ or ‘other’. Of the 268 patients who answered this question, 75% (202) said ‘reassuring’. A further 20% (54) rated the examination as ‘OK’. As one respondent commented, ‘I felt anxious before I came, I never thought going through an intrusive medical exam could make me feel more reassured’.

Five of the 268 patients said it was ‘traumatising’, one said it was both ‘OK’ and ‘traumatising’ and one said it was both ‘reassuring’ and ‘traumatising’. All of the patients who rated the examination as ‘traumatising’ said they would still recommend a friend in the same situation access the service and that the sensitivity shown by the doctor or nurse was highly rated. Two percent (5) ticked ‘other’, with one not adding any additional information; one patient who responded ‘other’ said ‘humbled, thank you’, one said ‘scary’, one said ‘it was good but a little painful of course’ and another said ‘ticklish, I couldn’t really feel it’ (Figure 4).

We asked the patients to tell us ways we could make the service better and received many positive responses of gratitude and that the service did not need any changes. When there were suggestions, many focussed on increasing awareness of the service:

Thank you so much. I had no idea where to even seek help. So glad I have. (Patient 151)

I think the service is great! Just tell more people about it and encourage more people to come. (Patient 74)

I think it’s really good, but it could be better by bringing more awareness as I didn’t know it existed but love your work. (Patient 245)

The services in hospital are great, perhaps – local GP with less experience would benefit from education by one of the staff in regards to this service. (Patient 43)

Figure 4. Patients’ rating of the experience of the examination when attended for a crisis response.

Of the five patients who rated the examination as ‘other’, four left comments (‘scary’, ‘ticklish, couldn’t really feel it’, ‘it was good but a little painful of course’ and ‘humbled, thank you’).

Discussion

In this survey, we achieved a high participation rate (80%, 291/365) of patients presenting to the SAS for an integrated crisis response after a recent sexual assault.

Patients were very positive about the service and would recommend a friend attend if they were in a similar situation. The large majority of patients found the examination to be reassuring, not re-traumatising. There is very little research on the perception of the examination from the perspective of the patient,1 and what research there is portrays the examination as being ‘experienced as uncomfortable at best, and traumatic at worst’.4 A recent review of the literature exploring how the medical forensic examination (MFE) can be improved for patients found the most important factors to mitigate the secondary traumatisation of the medical forensic examination was patient-centred, trauma-informed, forensically trained medical professionals who focus on the medical needs as a priority over forensics but are also skilled in effective forensic collection and documentation.4 The review highlighted the importance of empathy, belief and validation, careful explanation of procedures and giving choice to victim-survivors.4

Our research demonstrates that rather than just mitigating re-traumatisation, when the MFE is provided within a trauma-informed framework, with the patient at the centre of care, the MFE can actually be reassuring, with some patients indicating that the process was empowering.

Patients found the integrated team response, with psychosocial support provided by a counsellor and medical care provided by a doctor or nurse (with the option of a forensic service), to be extremely positive. Patients reported feeling safe, validated, reassured, believed, well cared for and respected. They also noted that such services need to be more visible.

With such a high participation rate, and the number of free-text responses provided, our study demonstrates that it is feasible to ask victim-survivors about their experiences rather than rely on proxy research. This is important for service quality assurance and improvement. We are incorporating patient feedback into community, ED and police education to raise awareness of the service and the benefits for victim-survivors in presenting for a health response.

We note the low referral rates from general practitioners (GPs). It is not clear if this suggests that there is a need to increase GPs’ awareness of sexual assault services and the benefits for victim-survivors. One patient specifically commented on the need for education of GPs. It is also possible that victim-survivors are not attending general practices after a recent sexual assault, presenting too late for a referral for a crisis response from the SAS, or that they are preferring to present to their GP for their health needs and do not want to attend a hospital setting for forensic testing. Victim-survivors might have barriers in presenting to a SAS that are not barriers when presenting to a general practice; for example, time and travel constraints, domestic violence with coercive control, childcare concerns or a preference to avoid attending the ED. These explanations could be explored in future research. It is also possible that victim-survivors are presenting to GPs and having their health needs addressed, such as STI screening, without disclosing the sexual assault. This highlights the importance of trauma-informed care for all patients.

Several patients indicated the service needed to be more visible. This is not something that has been highlighted in prior research to the best of our knowledge. Exploration of where people seek information and support after sexual assault needs to be prioritised and targeted for education.

Many of the victim-survivors of sexual assault commented on the difficulties and anxiety of presenting to an ED without prior arrangements being made, and not knowing what to say when they got there. Clearer pathways to sexual assault services, including how to access telephone counselling support prior to arrival, could go a long way to alleviating this anxiety. It is possible that many victim-survivors never present to the ED because of this concern.

This survey is part of a larger research project (the Acute Sexual Assault Presentations [ASAP] project) with next steps including in-depth interviews with some of these patients and surveys of the general public to explore knowledge and understanding of sexual assault services more widely. Finally, we will survey victim-survivors who did not access a SAS to identify barriers to presenting. In this research, we will be able to explore if survivors are preferring to present to their GP instead of an ED-based SAS.

Limitations

Survey data can have its limitations including participation issues and generalisability, as well as bias issues. We had very high participation with 80% of patients seen over a four-year period completing the survey, and we have documented valid reasons for most of those who did not participate. Therefore, we are likely to have a good representation of the service users of this SAS. But this represents those who were able to access care and is unlikely to represent the demographics of the many more victim-survivors in the LHD who did not access care. This SAS might vary from other SAS even within New South Wales (NSW). These variations might include different staffing arrangements and accessibility, especially in rural areas. Our service always involves the counsellor and medical staff working together from the start of the consultation, which might vary from other services. However, there are standardised workforce training and policies and processes across NSW. An adapted questionnaire is currently being used in a rural SAS in NSW, which could demonstrate similar results or highlight differences. Response bias such as social desirability bias and agreement bias, when participants might respond in the way they think, even subconsciously, is acceptable, needs to be considered. We tried to minimise this with the survey design and providing privacy to complete and submit the survey at the end of the clinical interaction so participants could feel confident being critical; however, it is possible this potential bias might skew our results to the positive.

Conclusion

The present study results demonstrate that sexual assault victim-survivors who presented for an integrated health response after a recent sexual assault felt reassured and validated by their experience. Victim-survivors rarely felt distressed by their engagement with the SAS. Greater awareness of such services is important. Knowing that many people experience sexual assault, and the negative impact this can have, it is important that victim-survivors receive timely access to integrated SAS that provide an empowering response by addressing psychosocial needs, medical needs and the option of engagement with the justice system.