Nursing home facilities in Brazil are privately owned; they are independent of the government and not included in the health insurance companies’ portfolio. The quality of assistance offered is varied and depends on the investment that each company decides to make. The best-quality nursing homes have a responsible clinical staff and a doctor who visits the facility daily, coordinating the nursing team and interacting with families. This difference in the quality of care proved to be important for facing the pandemic. The COVID-19 epidemic arrived in Brazil three weeks after it reached European countries and the US. Nursing homes for the elderly constituted a weak point deserving great attention, as was reported from the beginning.1–4

The current COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in difficult and unprecedented times. The efforts of all health professionals, each with their own competencies, are essential. While researchers and scientists struggle to find effective therapeutic resources, those on the frontline devote their best efforts to the clinical care of affected patients. With each passing day, the care of the health team itself is essential – not only physical care (for which all possible measures are taken in each case), but also attention to mental health. A discouraged, pessimistic doctor with no perspective is not helpful, and that attitude causes insecurity in patients. Practitioners’ self-care is a clear priority and is an area in which senior doctors and medical educators could provide guidance.5

Priority management: Providing a real and objective perspective of the scenario

It is not our goal to design an epidemiological study of the behaviour of the pandemic, nor to establish the bases of therapeutic protocols. It is to describe the daily reality that is experienced in this scenario and the preventive measures taken by our team. An excessive and disproportionate concern for the global problems that the world is facing does not help – and even hinders – each professional to take care of their own responsibilities in their specific sectors.

Thus, knowing how to tabulate daily the evolution of patients each professional has been entrusted to care for – the hospitalised, the deceased and, very importantly, those who have recovered and been discharged – provides a sense of reality. Global information, which is available to anyone, while important for health policies, is not overly relevant to what each professional faces on a daily basis. Such information can generate an anticipated concern and, even worse, distract professionals from their own responsibilities. It is possible – to adapt an old saying – that too much focus on the forest can prevent you from seeing the trees that need help.

In order to assist with this issue, our organisation of family practice physicians in Brazil, SOBRAMFA – Medical Education and Humanism,6 has disseminated recommendations through a series of short videos (‘Medical humanism in times of crisis’)7 that help professionals to maintain an objective view of the reality they are experiencing.

Managing nursing homes: Actions taken

We learned from global reports on nursing homes that waiting for clinical signs to provide isolation, treatment or referral to hospitals led to worse results, with a greater number of infected, sick and deceased patients.8–10 We also realised that – in addition to closing the home to visitors, using personal protective equipment and training the staff on how to use it – conducting periodic testing of all patients and employees regardless of symptoms makes the difference.

Based on this global experience, we closed the residences to visitation at the end of March. The resident guests remained isolated from all visits by family members. The only contacts of the guests were health professionals, who were protected according to the protocols adopted globally.

At this point, more than ever, personalised communication with families was prioritised. It is not enough to ‘shield’ the residential guests from visitation; it is also necessary to inform families, resolve doubts and explain the reasons for all these measures. This was especially true for the families of critically ill patients who had to be referred to the hospital, for whom contact was facilitated with the doctors acting at the hospitals. For the guests, who are used to the environment of the nursing home, the feeling of isolation was relative without constituting an additional problem, since they maintained their routines interacting with the staff.

All guests – including those who were asymptomatic – were tested for COVID-19, and those who tested positive were isolated from the rest of the community. This process was well accepted by the families; in fact, many had the expectation that they would take the test, as it was representative of better care according to the daily information they received from the media.

The publication of our experiences11 and the release of a special short video12 helped to support the health team and the families, showing that we were available to help at all times, inspiring serenity and compassion. That specific effort in communication also made our actions transparent and available to the scientific and healthcare worker community.

Results and lessons learned: Being there for patients and families

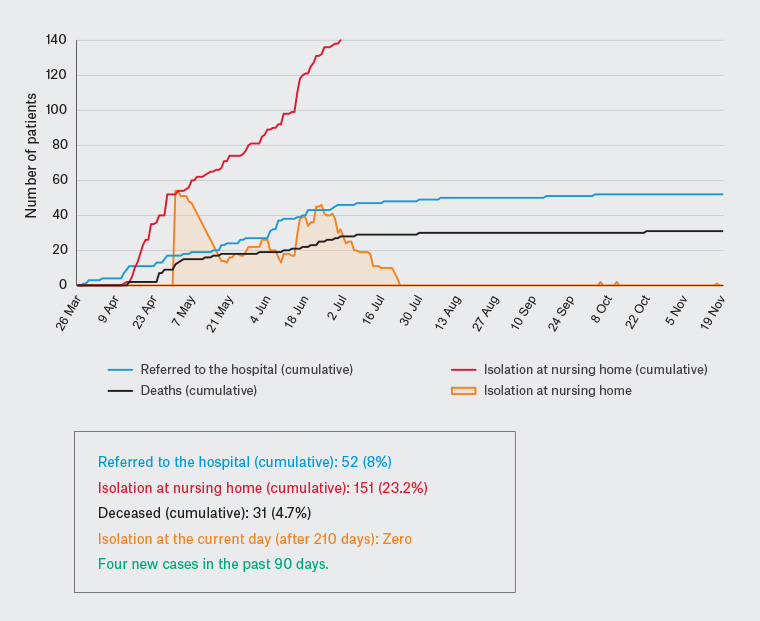

SOBRAMFA doctors coordinate the care of several nursing homes, with more than 650 guests in total. Figure 1 shows the monitoring of this scenario over 210 days (29 weeks) of the pandemic. Of the 650 guests, 8% (52) needed to be referred to the hospital. There were 31 (4.7%) deaths, and most were in the hospital. There were 151 (23.2%) patients with COVID-19 isolated in the nursing home. Four new cases were reported in the past 90 days, and currently there is no guest in isolation. The numbers are encouraging, especially considering that it is a population of high average age and risk.

Figure 1. Monitoring of COVID-19 by SOBRAMFA at several nursing homes for the elderly (650 guests) – follow-up of 210 days (29 weeks)

These outcomes are the result of the daily presence of SOBRAMFA’s medical team, including on weekends and holidays. It is known that the institutionalised elderly care sector lacks the real and active presence of the doctor, which is often represented by visits with some regularity to cover complications, and many actions that are delegated to the nursing team. There was no self-evident solution to obtain these results, only the real and active presence of SOBRAMFA doctors who were there for guests and families as well as providing support to the health team.

First published online 30 November 2020.