One in four Australians, or 5.3 million people, have at least two of the following chronic diseases: arthritis, asthma, back pain, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes or a mental health condition.1 The rate is even higher for females, those over the age of 65 years, or those living in rural and regional areas, or in deprived circumstances.1,2 Australia is not alone – prevalence rates for multimorbidity are high around the world.3,4

Patients with multimorbidity are often managed in primary care.2,3 A retrospective cohort study of 99,997 adults across 182 general practices in the UK found that most primary care consultations involved patients with multimorbidity.5 Multimorbidity involves greater clinical complexity, more frequent consultation, risk of polypharmacy, and higher treatment burden.6 An Australian study of patients with chronic illnesses and their carers identified that significant challenges contributing to treatment burden include:7

- financial burden

- extensive time and travel demands

- accessibility of services

- lack of coordination of healthcare

- difficulty managing medications.

Management guidelines exist for many single diseases; however, multiple and potentially contradictory recommendations are unhelpful for patients with multimorbidity.3 Clinicians need to find ways to treat people, not diseases.8

Guidelines for multimorbidity interventions are emerging.9,10 Evidence from reviews and expert consensus guidelines emphasise the importance of eliciting patient preferences, identifying common ground, developing a shared treatment plan, and building and maintaining a relationship with patients living with multimorbidity.11,12 With the aim of improving health and wellbeing, recommendations also include the potential benefit of focusing on lifestyle factors that have an impact on health across multiple health conditions.9,13 In short, patient-centred practice is needed to build a treatment plan that works for individual patients.

General practitioners (GPs) play an important part in supporting patients to identify their health needs and priorities, and navigate a fragmented and complex health system.6 An integrative and patient-centred approach has long been the domain of GPs by guiding patients through complexity to promote health.14 Working through the complexity of the healthcare system is a daily part of general practice; recommendations to further support patients with multimorbidity need to be feasible and effective in this context.15 Motivational interviewing offers a skill-based approach to achieving the broad aims of multimorbidity intervention. It is an approach to clinical communication that fits with multimorbidity recommendations, and is worthy of further consideration.13

Evidence from systematic reviews supports motivational intervewing as an effective approach for behavioural change across a range of behavioural domains that are relevant to multimorbidity.16,17 More than supporting behavioural change, motivational interviewing is an approach to working with patients by developing a partnership, eliciting and accepting the patient’s perspective, values and autonomy, and meeting the patient with empathy and compassion.18 In a systematic review conducted by Rubak et al, motivational interviewing in general practice was found to be more effective than routinely giving advice across a number of behavioural domains.19 The use of strategies consistent with motivational interviewing, such as reflective statements, advice with permission, and purposefully eliciting patient ideas, has been associated with improved weight reduction outcomes in patients.20

A motivational interviewing conversation is one where the clinician engages with the patient and supports behavioural change through a deliberate focus on the patient’s preferences, needs and values. Motivational interviewing conversations are helpful in promoting health behavioural change. This alone makes motivational interviewing an approach to communication that is worth considering for use in general practice.21 This article examines how motivational interviewing might be useful in assisting patients who are living with multimorbidity to navigate the complexity of multiple clinical guidelines, where they exist, and address what matters to them. In this light, motivational interviewing is a framework that benefits patients by bringing together the patient’s self-knowledge and the GP’s knowledge, to build an individual treatment plan.

The following case study of a patient with multimorbidity is based on the most common chronic conditions and risk factors seen in general practice, as reported by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.1

Case

Sue, a new patient at your practice, has made an appointment because her usual GP has retired. Sue is 40 years of age, has asthma, chronic pain from a back injury, and a body mass index (BMI) of 36 kg/m2. You welcome Sue into the consultation room and ask her what has brought her in today. Sue answers,

My back has been really bad this week and I just can’t get going.

At various points throughout the consultation, Sue also says,

I wake up in pain, and my asthma is awful, especially in the cold weather.

I keep gaining weight and even though I walk most days, I know I’m really unfit.

You health professionals are always telling me to exercise more and eat better, but I hate diets and I’m not living on salad, and I’m not joining the gym!

It’s true, I feel a bit better when I cook for myself, but getting organised to do it is too hard most days.

I really have been feeling low, but I’ve been this way for so long that I don’t know any different.

I just can’t see a way through it.

I don’t want to talk to some stranger about how I feel – it’s none of their business.

I don’t know if there’s any point in talking to you either, you all tell me the same stuff, and I’m really not stupid, you know.

Clinical assessment is an essential component of multimorbidity intervention.9,12 Sue’s statements raise a number of physical issues and highlight that, as is true for many people living with multimorbidity, clinical assessment of depression is indicated.9 Sue seems overwhelmed and ambivalent about making changes. Motivational interviewing may offer a framework to support a helpful conversation. There are four processes that shape an approach to clinical care informed by motivational interviewing: engaging, focusing, evoking and planning. While the processes are not linear, and can be revisited at any time in a clinician–patient relationship, engagement necessarily comes first.18 In this article, we will step through each process, using Sue’s case study to highlight specific motivational interviewing strategies. The strategies described can be used in a flexible manner at any point in a consultation.

Engage: Connect with the person

Patients with multimorbidity can feel overwhelmed, distressed or disheartened. In addition, they have often seen many health professionals and received the same advice. Figure 1 presents some of the helpful ways to engage with patients like Sue, and the ways in which reflective listening might be applied to demonstrate empathic understanding, support patient autonomy, and to defuse interpersonal discord.

Focus: Explore options to find a helpful focus

Helping people make changes starts with finding a focus. Sometimes, this is simple when the patient and clinician are both clear that the behaviour change proposed is one that supports health. However, in healthcare, and particularly with patients who have multimorbid conditions, there can be so many potential target behaviours that it can feel overwhelming for GPs and patients; this seems to be the case for Sue.

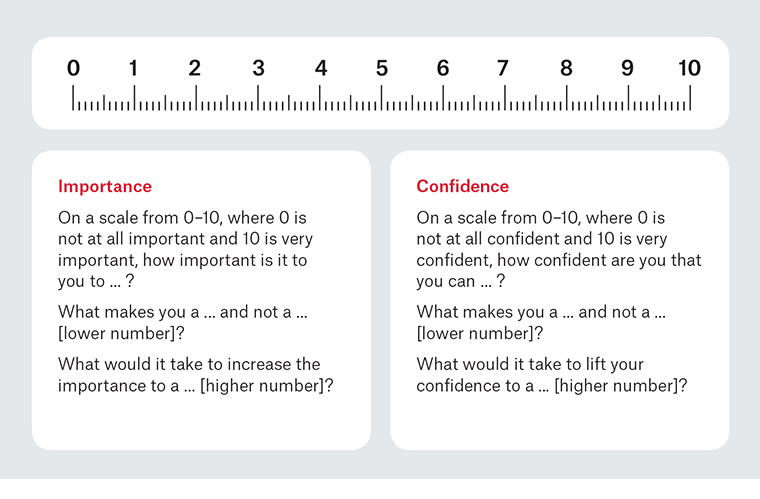

Agenda mapping is a skill that can help to find a focus that is personally meaningful for the patient and informed by clinician knowledge. The first step in agenda mapping is to generate the potential behaviours for change by asking patients what they think. A GP might say to Sue, ‘There’s a lot going on for you at the moment; you’re worried about your asthma, your back pain, changes to your weight, and you’ve been feeling down recently. What do you think is the most important issue to start with?’ This is also the time to introduce or add a difficult topic if the patient does not identify an issue that you consider important and likely to influence the outcome, by seeking permission to include this in the conversation. For example, ‘Is it okay if I suggest something … that others have found helpful/that might be helpful for you?’ Using an importance scale can be a useful way to determine the relative importance of each behaviour, and assist in selecting one that is meaningful to the patient (Figure 2).18

/McKenzie-Figure1.png.aspx?lang=en-AU)

Figure 1. Helpful responses to engage, respond to arguments against making changes, and to defuse discord18

Figure 2. Importance and confidence scaling18

Evoke: Listen for reasons, preferences, strengths and values

Questioning is a core part of assessment and practice in healthcare, yet questioning has traditionally been doctor-centred and not patient-centred.22 Open questions are those that cannot be readily answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’, or a single word. Open questions are a foundation skill in patient-centred care and motivational interviewing, because these questions enable your patient to tell you what they know, feel, understand, value and prioritise. While some patients are reluctant to talk, including adolescents who may make frequent use of answers such as ‘dunno’ or ‘sort of’, it is very difficult to establish a collaborative relationship if a consultation is stuck in the question–answer trap.18

Clinicians sometimes fear open questions because they think their patients will talk endlessly or about things that are not relevant. Adding structure to consultations may limit the risk of unhelpfully prolonged consultations. Guiding the conversation to what is helpful is an important skill, particularly in a time-limited consultation. In motivational interviewing, any patient statement about making a positive change is called ‘change talk’.23 The research and proposition behind motivational interviewing is that this method promotes change talk, and strengthens self-efficacy and behavioural intention.18,24 By encouraging patients to talk about their own reasons for change, clinicians have a pathway to strengthen and elicit commitment to change.24 Therefore, helpful questions are those that deliberately elicit change talk in conversations with patients. Figure 3 illustrates open-question stems with change-talk prompts and behaviour as a way of structuring helpful open questions, and provides some examples that might be helpful in working with Sue.

/McKenzie-Figure3.png.aspx?lang=en-AU)

Figure 3. Asking open questions to support behaviour change18

Plan: Make a plan together

As health professionals, we know many things, and it makes sense that we want to tell our patients what we know. However, eliciting information from patients may be more helpful than giving information.25 We tell people what to do in order to help them, but how often have you told someone what they need to do to improve their health, only to have them return for a follow-up appointment without having made any changes? Motivational interviewing is a way of being with patients that deliberately steps away from telling, confrontation and coercion. Indeed, confrontation is considered a non-adherent and unhelpful behaviour in motivational interviewing.23 Paradoxically, confronting and coercing people may have a negative impact on behavioural change.20,26

In motivational interviewing, an elicit–provide–elicit framework is used to give advice (Figure 4). This framework is a way of aligning with the principles of evocation and collaboration in motivational interviewing. Patients are first asked about what they know, or what is important to them, and this information is used to provide a context for giving information or advice. Depending on what Sue has identified as most important to her, a GP might ask, ‘What do you know about managing asthma?’ Alternatively, start with a reflection from what Sue said, ‘You sound a bit worried about your weight and fitness; what ideas do you have about improving your health?’ Patients are also asked to reflect on the overall discussion and how it is helpful to them. Confidence scaling (Figure 2) may assist in the planning stage to build self‑efficacy. Scaling questions are deliberately asked in the direction of change in order to generate a strengths and preferences discussion, and to ask patients what will help them to successfully change.18

Summary

Multimorbidity is complex, and there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach that can be readily applied. Patient-centred care and communication skills that support healthy behaviours are recommended, but there is little guidance as to how to achieve these recommendations.27 Patients need support to navigate the minefield of recommendations that may apply to them. In the case study presented in this article, Sue has many potential target behaviours, including physical activity, dietary changes, medication compliance, pacing to manage pain, and engaging in psychological support. Given the challenges inherent in Sue’s initial statement about herself, and the long list of potential targets, it is easy to see the limitations of a traditional assess-and-advise model of practice. The four processes of motivational interviewing are helpful considerations, and it is likely to take more than one consultation to engage and find a focus with Sue. However, in working collaboratively with the patient, she is more likely to make a change. Motivational interviewing is patient-centred, and supports behavioural change by eliciting the patient’s own motivation for change.18 It is a well-articulated, evidence-based approach, and may offer particular promise to support and empower patients with multimorbidity to change unhelpful behaviours.

/McKenzie-Figure4.png.aspx?lang=en-AU)

Figure 4. Elicit–provide–elicit framework for giving information and advice in motivational interviewing18