With advances in cancer screening, detection and treatment, the number of people surviving cancer is increasing rapidly. In 2018, an estimated 140,000 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in Australia, with 1.1 million people having a personal history of cancer. This is expected to increase to 1.9 million by 2040.1 In its broadest definition, a person is a cancer survivor from diagnosis for the remainder of their life.2

Cancer survivors often experience long-term negative consequences of their cancer and cancer treatment, in addition to the risk of a cancer recurrence or a second primary cancer. Cancer survivors have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and osteoporosis.2–6 Many have long-term residual symptoms, with more than half of early-stage survivors reporting five or more symptoms of at least moderate severity 12 months after diagnosis,7 and fatigue, loss of strength, pain, sleep disturbance and weight changes up to five years after diagnosis.8,9 Cognitive impairment, fatigue and other symptoms can affect independent functional ability and return to work, decreasing financial security.10,11 Other common physical long-term treatment effects include sexual dysfunction, infertility and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.12 Late-term effects include second malignancies, and impaired cardiac and pulmonary function.12

Fear of cancer recurrence occurs in approximately 70% of survivors, with approximately 50% reporting fear of at least moderate severity,13 high levels of uncertainty about the future,8 and unmet needs focused on fear of relapse.14 Changes in social roles, support networks and family and intimate relationships often occur, creating added distress.15

To address these unique needs of cancer survivors, there have been a number of recommendations for delivery of survivorship care. The seminal report From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition defined essential components of survivorship care.16 These included prevention of recurrent and new cancers and late effects of treatment; surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, second cancers, and physical and psychosocial late effects; interventions for the consequences of cancer and its treatment; and coordination between the specialist cancer care team and primary care providers to ensure survivors’ health needs are met.

In 2017, Cancer Australia released a national framework to guide policy development and health system responses to cancer survivorship, focusing on improving the health and wellbeing of people living with and beyond cancer.17 National ‘optimal care pathways’ define recommendations for care across the cancer trajectory, including in the post-treatment follow-up (survivorship) phase, calling for ‘screening and assessment of medical and psychosocial late effects’ and ‘interventions to deal with the consequences of cancer and cancer treatments’.18

Despite these calls for action, care of cancer survivors in Australia continues to focus on cancer surveillance in the specialist setting without sufficiently addressing the concerns or needs of cancer survivors.19 With increasing awareness that cancer is a chronic disease for many people, a shift in emphasis is required to a more structured and multidisciplinary approach for prevention and treatment of symptoms, long-term complications and comorbidities to improve survivors’ health and wellbeing. To address this, the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA) Survivorship Group developed a Model of Survivorship Care outlining the critical components of cancer survivorship care with the aim of improving the care of Australians beyond cancer diagnosis and treatment.20

Methods

A multidisciplinary working group of experts from cancer, allied health, primary care and community-based organisations was convened to develop the model using a literature review and consensus processes where evidence was lacking. An iterative development process was undertaken including survey and feedback of COSA members and groups, professional organisations and national consumer advocacy groups.

Recommendations

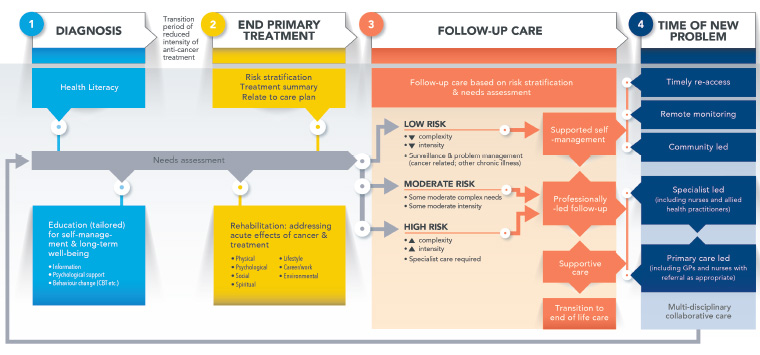

The model is outlined in Figure 1. Box 1 summarises the key recommendations.

Click here to enlarge

Figure 1. Model of Survivorship Care

Reproduced with permission from the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia

| Box 1. Clinical Oncology Society of Australia position on a model of care for early-stage cancer survivors after completion of primary treatment |

- Healthcare teams should implement a systematic approach to enhance coordinated and integrated survivor-centred care.

- Stratified pathways of care are required.

- Survivorship care should support wellness, healthy lifestyle and primary and secondary prevention while preventing and managing treatment-related symptoms, late-term effects and comorbidities, in addition to cancer surveillance.

- At transition to follow-up care, healthcare teams should develop a treatment summary and survivorship care plan.

- Survivors require equitable access to services in a timely manner, while minimising unnecessary use of healthcare services and resources.

|

1. Cancer healthcare teams should adopt a multidisciplinary, systematic approach to deliver coordinated and integrated survivor-centred care for all individuals from the time of diagnosis in partnership with primary care providers. Care teams should support self-management with integration between primary care, community support, non-government organisations and the specialist cancer care services.

Care should be integrated, with recognition that primary care may be best placed to provide preventive care and manage comorbidities, health risk factors (eg smoking, obesity, inactivity) and aspects of cancer follow-up.21 Most cancer survivors have comorbid illnesses22,23 and existing regular reviews with their general practitioners (GPs).24 Integrated care requires clear and timely communication between all healthcare professionals involved in a patient’s care. It is critical that professional roles are defined so that all aspects of needed care are provided without duplication.

2. Stratified pathways of care should be based on the needs and risk factors of the individual, treatment sequelae, existing comorbidities and capacity to self-manage (including assessment of health literacy). Risk of late effects is informed by treatment received. Needs require regular review and update to ensure relevance, with tailored education and rehabilitation as appropriate.

The COSA model recognises that post-treatment outcomes are informed by events during the diagnostic and treatment phases. Survivorship care should be tailored to the individual’s issues, needs and concerns (via a needs assessment such as patient-reported outcome or experience measures) and guided by their risk of developing late and long-term effects, recurrence or a new cancer.12,25 Care requirements will also be affected by comorbidities, social circumstances, health literacy and a person’s ability and desire to self-manage. Patients who wish to be involved in their own post-treatment cancer care should be provided with the information and support needed to self-manage, as is commonly done for other chronic disease management models (eg diabetes, asthma).21,26

3. In addition to cancer surveillance and management of symptoms and late-term effects, survivorship care should support wellness, healthy lifestyle and primary and secondary prevention.

Until recently, post-treatment cancer care focused on surveillance for cancer recurrence and/or new primary cancers.2 While surveillance remains important, lifestyle factors of survivors increase their risk of developing comorbid illnesses. Many struggle to meet Australian diet and physical activity recommendations.7,27 Survivorship care that supports healthy lifestyle behaviours is essential to reduce comorbid disease and maximise recovery and wellness. Referral to allied health professionals and evidence-based programs to assist cancer survivors to be physically active and eat well is critical in achieving these outcomes, as few patients achieve these goals without assistance. Practitioners should refer survivors to local services using chronic disease management GP plans, private health insurance and/or community-based low-cost programs to engage patients in effective behaviour change. Lifestyle behaviour change programs offer the best available options for long-term prevention, minimisation and management of symptoms and late effects of cancer and its treatments.

4. At transition to follow-up care, healthcare teams should develop a treatment summary and survivorship care plan as key tools to facilitate comprehensive care planning and communication between healthcare providers. The survivorship care plan requires regular review and update to document main concerns and agreed actions.

Transition from intense, acute specialist care to survivorship care can be facilitated by preparing the survivor with timely communication and provision of a treatment summary and survivorship care plan.2,18,20 This should include a treatment summary, outlining the cancer diagnosis and treatments, and a plan for follow-up, including strategies to remain well. Survivorship care plans should be completed by a member of the specialist cancer care team with input from the survivor and those involved in providing survivorship care. The care plans should clearly define the role of members in the care team, be regularly reviewed with the GP and other relevant health professionals, be updated as required and be communicated to all parties when changes are made to facilitate communication.

According to a recent systematic review, survivors who received a treatment summary and survivorship care plan reported a greater preference for shared care, were more likely to identify the GP’s responsibility in follow-up care, and had more cancer-related contact with their GP and increased implementation of survivorship care recommendations when compared with those who did not receive a treatment summary and survivorship care plan.28

5. Survivors require equitable access to services in a timely manner, while minimising unnecessary use of healthcare services and resources.

The burden of unmet need and disability after cancer diagnosis varies according to cancer type and treatment, place of residence and socioeconomic status, with patients from rural and remote Australia and lower socioeconomic status reporting more comorbidity, worse health outcomes and less access to cancer care and support.29 To ensure care is efficacious and equitable, effective survivorship care needs to be accessible through novel models of care delivery such as telemedicine and digital technology interventions as well as primary care–led services. An integrated approach that takes advantage of shared care arrangements between cancer services and primary care is likely to be more cost effective.30

Conclusions

An improved model of survivorship care is expected to result in better outcomes for survivors. These outcome measures may include improved duration of survival, reduced risk of cancer recurrence, decreased risk of late effects, better quality of life and improved functional and wellbeing outcomes. At present, the evidence basis remains incomplete, and successful implementation will require research, education, coordination and advocacy. The COSA Survivorship Model of Care provides a template for change, guiding the key steps for implementation into the future.