So we have inspectors of inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors. The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living.

– Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983)

The scrutiny of nursing home care has highlighted significant systemic shortcomings in care delivered at some nursing homes. In response, the Minister announced re-accreditation audits and a new Commission to oversee the aged care sector (new governance system),1 whose first task will be the delivery of a new Results and Processes Guide (new accountability system).2

The government proclaimed its new governance framework in the form of Quality of Care Principles,3 which have been operationalised through a multiagency process: the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare developed a Performance and Accountability Framework,4 which the Australian Aged Care Quality Agency translated into Accreditation Standards covering eight broad domains,5 which the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission translated into detailed expected outcomes criteria.2 The associated standards assessment guidelines and their accompanying provider self-assessment tool are heavily process-focused2 but, as providers emphasised, provide no clear guidance on how to implement, monitor or improve residents’ care and wellbeing.6,7

The crisis in the aged care sector is a systemic problem that emerged over time as a result of interactions of at least three difficult-to-reconcile goals:

- adherence to process-focused ‘governance and accountability requirements’

- optimal management of the complex ‘morbidity burden of aged care residents’

- the economically sustainable provision of a ‘skills- and staffing-level mix necessary to meet residents’ care needs’.

The problem: Addressing what matters in nursing home care

What matters most to nursing home residents is their health experience and quality of life.8,9 The following common scenarios illustrate the difference between approaches to care that are process based (adhere to a protocol) and outcomes based (adapt care to problems within their context):

- A usually stable resident with diabetes is given more insulin for an elevated blood sugar reading (as per protocol) but is not assessed for underlying reasons for this elevated reading, such as loss of appetite, an infection or a frank delirium (the necessary adaptive response).

- A resident, following a fall, is being assessed for injuries (as per protocol), but reasons for the fall – such as lack of mobility, pain, hypotension, polypharmacy – are not elicited and/or strategies to prevent future falls – such as physiotherapy, pain management and medication review (the necessary adaptive responses) – are not initiated.

Governance and accountability in aged care

While accountability (ie showing the discharge of one’s responsibilities) is necessary and desirable, the ultimate questions remain:

- Accountable to whom and for what?

- Which accountability measures ultimately ensure the best patient outcomes?

Understanding governance and accountability principles is a prerequisite for answering these questions. Governance refers to an organisation’s system-wide framework to ensure it has processes in place to meet its legal and ethical obligations. Governance frameworks in turn determine which process-focused and/or outcomes-focused accountability measures are being put in place.

Peter Drucker, addressing the issue of accountability, said, ‘There is a difference between doing things right and doing the right thing’.10 While the former addresses procedural correctness, the latter is outcomes-focused and encourages adaptive responsiveness to changing circumstances.

Drucker’s insights reflect the complex adaptive nature of the issues, problems and challenges facing organisations. Aged care providers have to manage the complex morbidity and associated care needs of their residents (Box 1 [B]), attract and manage a workforce composition with the required diverse skills (Box 1 [C]) and ensure all care meets accountability requirements (Box 1 [A]).

| Box 1. The systemic challenges of governance and accountability requirements facing aged care providers |

|

[A] Governance and accountability requirements

Accreditation Standards Handbook3

Sec 11 (1) The Accreditation Standards are intended to provide a structured approach to the management of quality and represent clear statements of expected performance. They do not provide an instruction or recipe for satisfying expectations but, rather, opportunities to pursue quality in ways that best suit the characteristics of each individual residential care service and the needs of its care recipients. It is not expected that all residential care services should respond to a standard in the same way. (p. 5)

The eight standards of the Single Quality Framework2

- Standard 1 Consumer dignity, autonomy and choice

- Standard 2 Ongoing assessment and planning with consumers

- Standard 3 Delivering personal care

and/or clinical care

- Standard 4 Delivering lifestyle services and supports

- Standard 5 Service environment

- Standard 6 Feedback and complaints

- Standard 7 Human resources

- Standard 8 Organisational governance

Assessment of Standards26

Explicitly emphasises that providers/management have processes in place to manage each standard.

Information about the service’s processes is also particularly important in the absence of tangible information about results for care recipients. It could include information that indicates:

- processes and systems are in place

- the processes and systems are effective. (p. 8)

Results are first defined as ‘management demonstrates …’ followed by statements such as: ‘confirm the appropriateness’, ‘corresponds with the achievement’, ‘met in the prescribed manner’ or ‘satisfied with how care is …’ |

[B] Morbidity burden of aged care residents

- 83% are classified as requiring high care27

- 60% have dementia

- 40–80% have chronic pain

- 50% have urinary incontinence

- 45% have sleep disorders

- 30–40% have depression

The need for residential aged care arises from increasing physical frailty, cognitive decline, emotional lability or social vulnerability. These declines make aged care residents prone to:

- acute delirium – most commonly caused by urinary and upper respiratory tract infections

- gait and balance problems – resulting in skin tears, falls and fractures

- polypharmacy – resulting in serious drug-drug interactions, and loss of physical and mental function

- behaviour issues – resulting from mental decline and emotional lability, physical disability and polypharmacy

- end-of-life care – requiring coordinated medical and nursing support for the resident and his/her family.

|

[C] Providing for the needs of aged care residents

The needs of residential aged care

Care involves three separate but interrelated domains:

- personal care – provided by personal care assistants and assistants in nursing

- medical care – provided by enrolled and registered nurses, mental health nurses, physiotherapists, podiatrists, dietitians and physicians

- social care – provided by lifestyle therapists, diversional therapists and volunteer activities such as musicians, artists or animal handlers.

Staff composition (2003 versus 2012)28

- Nurse practitioners (NPs): nil versus 0.2%

- Registered nurses (RNs): 21.4% versus 14.7%

- Enrolled nurses (ENs): 14.4% versus 11.6%

- Personal care attendants (PCAs): 56.5% versus 68.2%

- Allied health professionals/assistants (others): 7.6% versus 6.3%

Skills and cost (range)29

- NPs – Master’s degree: $37–38/hr

- RNs – Bachelor’s degree (four years at university): $25–42/hr

- ENs – Diploma (one year at university): $22–24/hr

- PCAs – Certificate III (five weeks at TAFE): $20–24/hr

- Others – Variable: $24–32/hr

Staff-to-patient ratios

- The Australian Health Care Act (1997)30 requires that providers ‘maintain an adequate number of appropriately skilled staff to ensure that the care needs of care recipients are met’.

- Current staffing levels can be as low as one RN per 100 residents.

- Victoria introduced staff ratios for a small number of publicly owned aged care homes:31

- morning shift – one RN per seven residents

- afternoon shift – one RN per eight residents

- night shift – one RN per 15 residents.

|

Accountability: To whom and for what

The key questions for accountability are: ‘accountable to whom’ – a command and control philosophy emphasising processes – and ‘accountable for what’ – an issues and goals orientation focusing on responsiveness, adaptability and learning.11 The former traces ‘who is responsible for what happened’, while the latter looks at ‘what has been done’ and ‘what has been achieved’.

The government’s governance and accountability statements and guidelines are vague in terms of resident outcomes while strongly indicating expected processes to be designed and followed. A process focus – codified in policies and procedures manuals – works sufficiently in manufacturing to prevent undesirable product variability. However, care and social services have to react to sudden unexpected changes in needs, demands and circumstances, necessitating high-level adaptive response skills.

False accountability arises when one applies rule-based processes to situations that are complex and in constant flux – those situations require adaptive responses and measures that corroborate their achievement. The weakness of rule-based hierarchical process-focused accountability is compounded when problems or emerging crises are unreported, putting individuals and the ‘organisation as a whole’ at risk.

Braithwaite’s studies in the aged care sector concluded that there is no clinical need for the proliferation of protocols and guidelines to cover every imaginable issue.12 Rather, he called for measuring the factors that matter to patient care and outcomes, something that he found to be an anathema to administrators who believe adherence to formalisms adequately shows adherence to legislative requirements, and that such adherence assures ‘high-quality care’ delivery.

How process- and outcomes-focused accountability differ

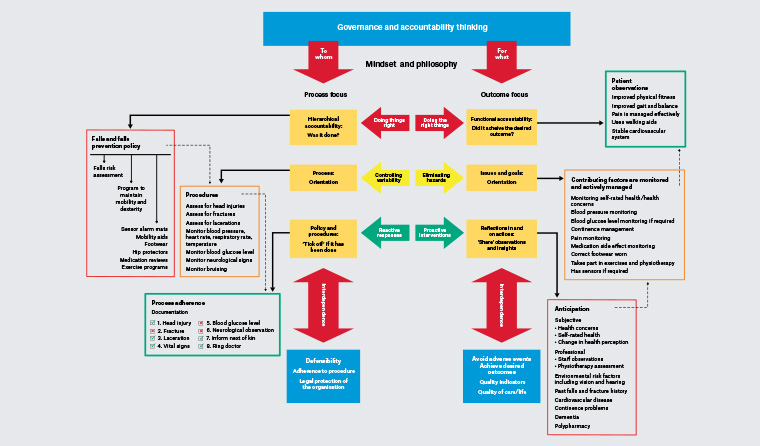

Figure 1 depicts the fundamental differences between process- and outcomes-focused governance and accountability thinking. ‘Defensibility’, measured as adherence to procedures, is the main driver behind process-focused accountability. In contrast, ‘avoid adverse events and achieve desired outcomes’, conveyed by quality indicators and quality-of-care/life measures, drives outcomes-focused accountability.

Click here to enlarge

Figure 1. Principles of process- versus outcomes-oriented governance and accountability frameworks – influence on policy design, staff priorities and impact on residents’ care

Aged care residents’ frailties frequently lead to falls. Current guidelines, designed by facility managers, describe each facility’s approach to falls and falls prevention. Staff will assess, on admission and at regular intervals, a resident’s falls risk and provide programs to maintain mobility and dexterity. The guideline names ways to manage falls risks such as the use of sensor alarm mats, mobility aids, appropriate footwear, hip protectors, medication reviews and exercise programs. Furthermore, the guideline states that the facility ensures that staff undertake education programs about falls prevention. The bulk of the guideline outlines in detail the steps staff must follow after a fall has occurred, and how to document observations and reporting requirements. A ‘post-fall flowchart’ reiterates the prescribed processes to be followed. Failure to provide evidence that each step in the guideline has been adhered to will result in staff being reprimanded and carries the risk that accreditors sanction the facility (personal communication, clinical services director).

An outcomes-focused approach would be anticipatory in nature – starting from the resident’s past falls and fracture history, their subjective health rating and their health concerns. The care team would jointly assess additional environmental risk factors before designing a resident-centred management program that ensures that all relevant issues are assessed and monitored daily. Anticipatory care that takes particular note of the person’s self-rated health, health concerns and anticipated changes in health has shown a reduction in preventable morbidity, hospitalisation and mortality.13–16 Effectiveness/complication rates and quality of care/life would be relevant outcome-focused accountability measures to show the performance of an ‘aged care facility as a whole’.17

Accountability should serve residents’ interests

Current accountability thinking focuses on defensibility – have the institutionally predefined processes been adhered to? It assumes, such as in engineering and production, that ‘doing things right’ will result in the desired outcomes; unfortunately, the reality of aged care shows that it frequently does not.

The alternative, a focus on avoiding adverse events and achieving desired outcomes, engages all parties in defining and redefining ‘what ought to be achieved’ – the prevailing method in most ‘service industries’.12 Working backwards from this outcome determines what actions need to be taken. It acknowledges that residents and their circumstances are in constant flux and that the ‘right thing’ that needs to be done will necessarily change – hence the core staff skill must be adaptability and team learning.17,18

The former approach is reactive, responding contemporaneously to incidents, while the latter is proactive, anticipating what is most likely going to happen and trying to avoid undesirable outcomes. Residents’ best interests are rarely served by showing that the right boxes have been ticked after the fact. Working with residents and constantly monitoring their progress and change enables steps to be taken to avoid incidents, although not all incidents can be prevented.

Answerability following detection of a serious event or a preventable outcome usually requires facility owners, staff and healthcare providers to explain and justify their conduct, and change must address underlying systemic deficiencies.17 Otherwise, sanctions are in order as ‘answerability without sanctions is considered to be weak accountability’.19

Conclusion

There is an international call for governments to put more emphasis on outcome transparency and less on process measurement12,20,21 – the failures of not doing so are currently being examined by the Australian Government’s Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au). This entails a change in thinking about governance of aged care facilities, and ultimately demands a different organisational structure of facilities and their leadership culture (Table 1).

Regulatory change remains demanding; the greatest challenge for facility leaders will be to reinforce a resident-focused culture shift. This not only requires behavioural and educational responses to manage ‘tricky problems on the floor’, but also resident-focused monitoring systems that enable staff to adaptively and quickly respond to emerging health changes (Appendices 1 and 2, available online only, comprise a suggested reporting format and dataset, and its usefulness to resident care).

| Table 1. Comparing process- and outcome-oriented organisations and their consequences |

| |

Control-focused |

Responsiveness-focused |

| Belief |

One cannot trust people |

We trust that:

- people take responsibility if allowed to do so

- people learn from each other

- mistakes/mishaps are learning/improvement opportunities

|

| Focus |

Who is wrong (individual focus)

Retribution |

What is wrong (system focus):

- process failures

- early warning signs

Improvement |

| Consequences |

Authoritarianism

Distrust

Limited engagement

Risk aversion

Hidden issues/failures

Stagnation |

Distributed leadership

Trust

Initiation to solve problems

Calculated risk taking

Openly discussed problems

Innovation |

Braithwaite12 summarises the differences as follows:

- protocols kill initiative under an atomistic pile of paper

- excessive demands for a task orientation distract attention from the people-oriented outcomes that matter

- protocols and guidelines create health and regulatory bureaucracies that miss the big picture* by being excessively systems oriented

- subjective assessments are reliable – and in constant use to improve outcomes in other service industries.

|

| *Braithwaite’s description of the status quo: ‘In nursing home regulation today we find public mandating of the preparation of all manner of compliance plans, often combined with a requirement for committee meetings associated with them, with obligations to provide minutes of such meetings to inspectors and the risk of citations from inspectors if these processes are not working. Examples are nursing home plans for quality assurance, individual care plans for all residents, in-service training plans, staff planning, building design, infection control, pharmacy, social services, even grooming plans. In some jurisdictions, with some of these there are public requirements that outsiders be required to participate on committees that revise plans and monitor continuous improvement, as in US state rules that require family members of residents to be invited in writing to quarterly care planning meetings for their loved one’. |

It is well understood that complex problems cannot be solved with clear and simple solutions, however well intended.22 As Ackoff showed, problems in organisations arise from interactions among their members rather than any one individual’s action.17 Hence the imposition of new process-focused accountability requirements will result in ‘foreseeable’ unintended consequences; the threat of sanctions and penalties23 necessitates that managers and nursing staff must spend much of their limited time on compliance requirements, which in turn reduces time available to attend to interactions that enhance residents’ physical, emotional, social and cognitive wellbeing.24

Time is a limited resource but is essential to provide good care and to achieve best possible quality-of-life outcomes.25 The delivery of best possible services in itself is complex, as the needs of nursing home residents change frequently and often unexpectedly; realising quality care delivery requires perpetual adaptation and improvisation (ie learning).

High standards of care command as much time as possible being spent with residents and as little time as necessary with paper/computer work. Only then will the attributes called for in the Aged Care Single Quality Framework,5 namely that care should achieve the maintenance of independence and dignity of residents, be realised.

The litigious attitudes of our society have led to the view that defensibility is best achieved by enforcing a rigid process-focused accountability model. Available evidence suggests that an outcomes-focused accountability model is equally defensible and enforceable, and is more closely aligned with the complex adaptive demands of aged care residents. This outcomes focus would readily help to reshape organisational and care delivery practices, the expected outcome for those who have called for a Royal Commission.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2