Changes in living conditions – for better or worse – typically result in changes in patterns of disease and health needs. The rise of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancers and respiratory ailments in post-industrial society1 has led to the rise of an adjunct discipline called ‘lifestyle medicine’ to help better manage these conditions. Lifestyle medicine has been defined as ‘the application of environmental, behavioural and motivational principles, including self-care and self-management, to the management of lifestyle-related health problems in a clinical setting’.2 Lifestyle medicine differs from non-medical clinical practice in that the former may include medication (eg for smoking cessation or hunger control); lifestyle medicine adds to conventional medicine in that it more closely examines environmental and distal determinants, as well as individual behaviours, that influence disease. A comparison between the two approaches can be found in Table 1.

| Table 1. Differences between conventional and lifestyle medicine approaches in primary care |

| Conventional medicine |

Lifestyle medicine |

| Focus on risk factors and proximal determinants of disease |

Focus also on medial and distal determinants of disease |

| Patient more a passive recipient of care |

Patient should be an active partner in care |

| Patient not required to make big changes |

Patient often required to make big changes |

| Treatment usually short term |

Treatment almost always long term |

| Emphasis on diagnosis and prescription |

Emphasis on motivation and compliance |

| Less emphasis on the environment |

Greater consideration of the environment |

| Involves predominantly medical specialties |

Includes greater allied health input |

| Doctor generally acts independently on 1:1 basis |

Doctor is coordinator of a health professional team |

Professional associations in lifestyle medicine have formed in 18 countries around the world, and others are currently being established; a Global Lifestyle Medicine Alliance exists, and a growing number of texts and university courses are now available. Texts range from those with a general consideration of lifestyle and environmental aetiologies in modern disease2–5 to those discussing lifestyle involvement in specific diseases.6–8 Still, the structure and pedagogy of this discipline is in its infancy. The current generic structure of the field is summarised here under four main headings: the science, the art, the materials and the procedures. Specific aspects of the discipline are covered in other articles in this issue of Australian Journal of General Practice.

The science: The epidemiology of chronic disease

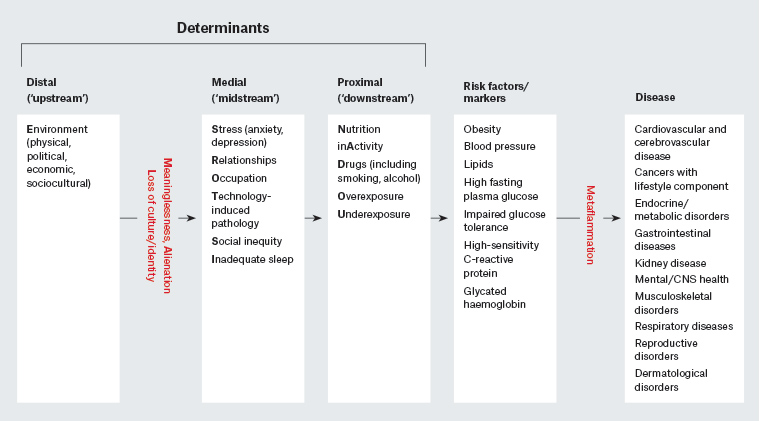

When considering infectious diseases, ‘causality’ is ascribed to biological causes (‘germs’) using classical principles such as Koch’s postulates.9 For chronic diseases and conditions, causality is more complex.10 The closest equivalent is describing ‘determinants’ and risk factors or markers at various levels. These form an acronym (NASTIE MAL ODOURS; Figure 1) which has been canvassed extensively elsewhere2 and hence will not be repeated in this article.

Figure 1. A hierarchical approach to chronic disease determinants

CNS, central nervous system

We have also previously discussed the fact that while some of these determinants (eg nutrition, [in]activity, smoking – or ‘forks, feet and fingers’) are predominant, they form the tip of an iceberg, with other determinants at the base.2 Although each may independently affect the development of chronic disease, recent work suggests that it is more realistic to think of interactions as an in vivo ‘systems’ model both within and between determinants,11 in contrast to that which is characterised by a simple linear approach.

The discovery of a form of low-grade, systemic inflammation (‘metaflammation’) in the 1990s12 assisted this process by ascribing a monocausal focus similar to the germ theory for chronic ailments, which have until now been dealt with in ‘silos’. Several analyses have identified inflammatory ‘inducers’ that underly most, if not all, the determinants that lead to the major chronic disease categories.13–15 The term ‘anthropogens’ has been used as a collective term to provide a single focus for these chronic disease determinants, similar to the germ theory of infectious diseases in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Anthropogens are defined as ‘man-made environments, their by-products and/or lifestyles encouraged by those environments, some of which have biological effects which may be detrimental to human health.’16

Anthropogens have varying levels of potency depending on a range of factors such as genes, environment and exposure. Isolating nutrients from foods ignores the interactive relationship of nutrients found in complete meals, just as considering inactivity, sleep or social factors in the absence of nutrition provides only part of the answer to chronic disease manifestation. The systems model of interactions between determinants is an important aspect of a modern lifestyle medicine approach to chronic diseases and conditions because it implies that all influencing determinants, and not just the obvious, need to be managed for an optimal health outcome.

The art: Expanding motivational and contact skills

The basic clinical skills required for lifestyle medicine are similar to those necessary for conventional healthcare – diagnosis, prescription and counselling in particular. However, in lifestyle medicine the components require a significant emphasis on motivation and can include both academic and professional skills in behaviour change. These comprise skills used in persuasion and advertising, such as coaching,17 coaxing and nudging patients from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation to facilitate change in lifestyle behaviours.

Diagnosis in lifestyle medicine is focused more on determinants and their drivers, rather than the disease itself. Pharmaceutical prescription is still important but is best seen as an adjunct to therapeutic lifestyle prescription and intervention. In cases of iatrogenesis, this may also include programmed deprescription to reduce ineffective medication use or combinations.Counselling in lifestyle medicine relies heavily on motivational interviewing but also focuses on self-management. This can come through such techniques as general practitioner management counselling, referrals, peer-to-peer contact, social prescription and support through shared medical appointments (outlined later in this article).

The materials: Identifying and using the available tools

Lifestyle medicine ‘tools’ mainly centre on the concept of the ‘quantified self’. The role of the patient evolves from a minimally informed recipient to an active collaborator in the patient–provider relationship. The digital revolution has resulted in a vast array of tools that can be used to monitor and provide feedback on determinants related to lifestyle such as exercise, cardiac activity, blood pressure, blood glucose, sleep and a growing list of other factors. Mobile health (mHealth) is becoming more widespread, with monitoring and advice applications available on mobile phones. Internet reminders, education and information about disease management are increasingly more available and conveniently accessed through wearable devices,18 although the effectiveness of some of these remains to be proven.19 Self-help assistance and virtual games that are instantly accessible using internet access can add to the tools available.

The procedures: Developing the actions to be carried out

Several existing and developing procedures are appropriate for lifestyle medicine. These include existing practices from conventional medicine – such as referral, medication and surgery – as well as some new, albeit currently less evidence-based, procedures. These are covered in more detail elsewhere,2 but discussed here in summary.

Self-management training

This should be a component of all lifestyle-related chronic disease management. Training can be standalone and range from individual assistance given by a health professional20 to group learning processes.21

Shared medical appointments

Shared medical appointments (SMAs) are ‘… consecutive individual medical visits in a supportive group setting where all can listen, interact, and learn’.22 They have been used in several countries to overcome the difficulties of time-limited 1:1 consultations developed historically to manage more acute disease. SMAs provide more time with the doctor, faster access to care, increased peer support and greater opportunity for self-management.22

Programmed shared medical appointments (pSMAs)

These are defined as ‘… a sequence of SMAs in a semi-structured form providing discrete educational input relating to a specific topic’.23 Programmed shared medical appointments (pSMAs) allow for a set number of SMAs run in a sequenced ‘active learning’ format coordinated by an SMA facilitator (practice nurse/allied health professional) with generic training in conducting SMAs and specific training in the disease topic. A doctor provides individual sequential consultations during part of the session, with participation and input of the group. pSMA ‘packages’ have been developed in Australia24 and are currently being evaluated for a range of ailments including weight loss, type 2 diabetes, smoking and chronic pain.

Social prescription

As well as referrals to other health professionals, referrals can be to a range of activities, interests and services in a community, as well as to community centres with lifestyle programs. The well-established mental health ‘Act-Belong-Commit’ program developed in Western Australia25 now includes screening processes to professional websites (eg for depression/anxiety) or in the form of a ‘green prescription’ for physical activity. This has yet to be evaluated in the clinical medical setting.

Peer-to-peer learning

Although most commonly used in health services training, peer-to-peer learning has value in lifestyle medicine, where people who have had a specific disease for a long time can help others with the same disease, either through online or face-to-face interaction.26 This can be an offshoot of other procedures such as SMAs or social prescription.

Telephone triaging

Telephone triaging is used increasingly in the UK to direct patients to the most appropriate form of management or type of program. This allows physicians to better make use of professional time to deal with the wide span of chronic diseases. Cases are triaged by telephone within a centre according to levels of need, with different health professionals assigned to counsel for low-acuity chronic disease management cases, leaving the physician to deal with higher-acuity cases. This means that patients with long-term conditions, which require more attention and self-management opportunities, can get the required level of help while the centre manages limited resources.

Conclusion

Although not a departure from conventional medicine, lifestyle medicine provides an adjunct approach to managing lifestyle and environmental determinants of many modern chronic diseases. Lifestyle medicine fits a role between clinical medicine and public health, encouraging clinicians to consider both the proximal and distal determinants (anthropogens) of chronic disease, as well as markers, risk factors and behaviours. Self-management, SMAs, social prescription (and deprescription), telephone triaging and peer-to-peer assistance provide adjunct procedures for conducting lifestyle medicine consultations. New tools such as mHealth may be useful to capitalise on modern technological developments and increase treatment options. This is a work in progress, and the field will expand considerably with testing and evaluation of these approaches.

Key points

- Chronic diseases now predominate over infectious diseases in Western societies.

- Lifestyle medicine is an adjunct discipline designed to aid chronic disease management.

- Lifestyle medicine adds importantly to conventional medicine in four areas: 1) the science, 2) the art, 3) the tools and 4) the actions.

- Although lifestyle medicine is now recognised worldwide, it is still a work in progress.