Case

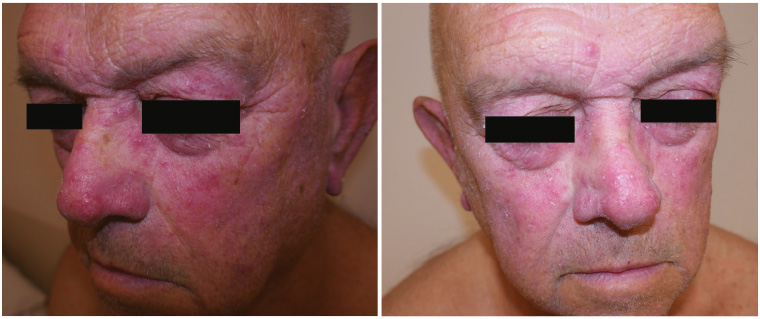

A male mechanic, aged 67 years, presents with a new-onset facial rash of six months’ duration. The rash started around the preauricular region and spread to involve bilateral cheeks and forehead. He now has an erythematous papular rash over the malar region and the forehead with coarse white scales (Figure 1). The perioral region and nasolabial folds are spared, suggesting photosensitivity. The patient mentions mild itchiness associated with the rash.

Figure 1. Erythematous facial rash on a male patient

Question 1

What conditions commonly present in this morphological fashion?

Question 2

What additional history may be useful in refining the differential diagnosis?

Answer 1

The differentials can include:

- papular rosacea

- seborrheic dermatitis

- contact dermatitis

- tinea faciei

- dermatomyositis

- acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- medication-induced facial erythema (eg topical or systemic corticosteroids).

Answer 2

Helpful information that can assist in refining the differential diagnosis in this case can include:

- history of flushing with various triggers – rosacea is associated with flushing

- response to sun exposure – rosacea, dermatomyositis and lupus will worsen

- constitutional symptoms – common in connective tissue disease

- exposure to external agents such as perfumes or aftershave – potential causes of facial contact dermatitis

- cutaneous lesions on other parts of the body – rosacea is usually confined to the facial area.

Case continued

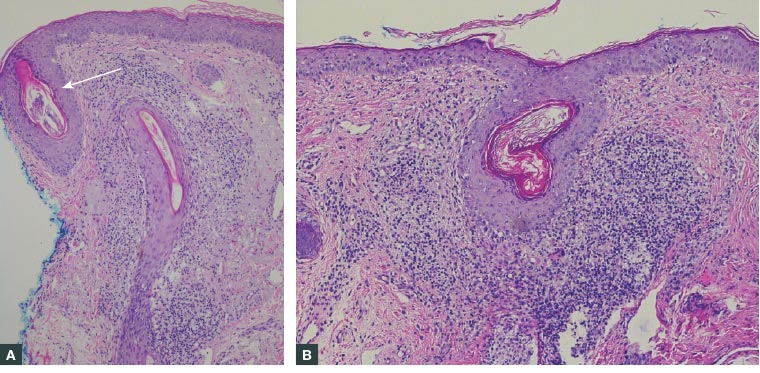

On further history-taking, the patient reports that he has not had any photosensitivity, constitutional symptoms or other cutaneous lesions in the past six months. He does not have a history of flushing and has not used any fragrances or perfumes. The only topical preparation he has been using for his rash is a plain moisturiser. His medical history is relevant for polythycaemia rubra vera, which is treated with hydroxyurea 10 mg twice daily. Punch biopsies are performed because of the concerning medication history and cutaneous scales that are atypical for rosacea. The biopsy shows moderate perifolliculitis at the infundibulum and isthmus on a background of vascular ectasia and Demodex mites (Figure 2).

Fungal scrapings and tests for antinuclear antibodies, double-stranded DNA and extractable nuclear antigens are negative.

Figure 2. Punch biopsy specimen from right medial cheek and zygoma

A. Demodex mite (white arrow; haematoxylin and eosin, × 100); B. Chronic folliculitis with background vascular dilation and distension (haematoxylin and eosin, × 100)

Question 3

Of which condition is the skin biopsy result suggestive?

Question 4

What is the concern of polythycaemia rubra vera and hydroxyurea use for this patient?

Question 5

What is the appropriate treatment for this condition?

Answer 3

The punch biopsy histopathology is suggestive of papulopustular rosacea with increased lymphocytic infiltrate in the infundibulum and isthmus.1,2 Vascular ectasia is also a common but non-specific finding in the rosacea.1 Patients with rosacea have significantly higher prevalence and degrees of Demodex mite infestation, which may play a role in the pathogenesis of this condition by inducing inflammation.3

Answer 4

Medication-induced dermatomyositis is rare but well reported.4 It is most commonly associated with hydroxyurea, which is a chemotherapeutic medication used to treat conditions such as polycythaemia vera, chronic myeloid leukemia and essential thrombocytopenia.4 Medication-induced dermatomyositis can present with a photosensitive heliotrope rash that should be considered as a differential with this patient.

Answer 5

The patient should be reassured of the benign nature of this condition. If specific triggers or exacerbating factors (eg wind, exercise, spicy food, hot drinks) can be identified, avoiding the trigger can be beneficial.5 Ultraviolet exposure exacerbates rosacea through the production of reactive oxygen species.5 Daily sun protection can be of benefit.5 Emollients are beneficial for rosacea in decreasing transdermal water loss.

Medical treatment of rosacea can be optimised according to the clinical subtype. Mild rosacea responds well to topical metronidazole and azaleic acid. Papulopustular rosacea can be managed with antimicrobial agents such as doxycycline and erythromycin at a sub-antimicrobial dose for their anti-inflammatory properties.5,6 Oral isotretinoin can be used to manage papulopustular as well as phymatous rosacea.6 Ivermectin (1% cream) is a promising emerging therapy for rosacea, targeting the role of Demodex mites in the pathogenesis of rosacea.7 It should be noted that topical ivermectin is not funded by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and costs approximately $50 on a private script. It is applied once daily for up to four months.6 A burning cutaneous sensation is the most common side effect; nevertheless, the tolerability is generally excellent.7

Case continued

This patient was treated with oral doxycycline and topical ivermectin. At his next visit to the clinic, his condition had improved, with significantly reduced erythema.

Summary

The aetiology of facial rash is diverse, and the diagnosis is not always straightforward. While conditions such as rosacea constitute the majority of facial erythema diagnoses, it is worthwhile to consider less common aetiologies, which can include more sinister autoimmune entities such as systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis.8

Biopsy is usually not required in the setting of diagnosing rosacea, but it may be helpful in cases when the presentation is atypical or the differential diagnosis remains unclear.3 The management options for rosacea are diverse and depend on the subtype of the disease.