Background

Recommended first-line management of lower limb osteoarthritis (OA) includes support for self-management, exercise and weight loss. However, many Australians with OA do not receive these. A National Osteoarthritis Strategy (the Strategy) was developed to outline a national plan to achieve optimal health outcomes for people at risk of, or with, OA.

Objective

The aim of this article is to identify priorities for action for Australians living with OA.

Discussion

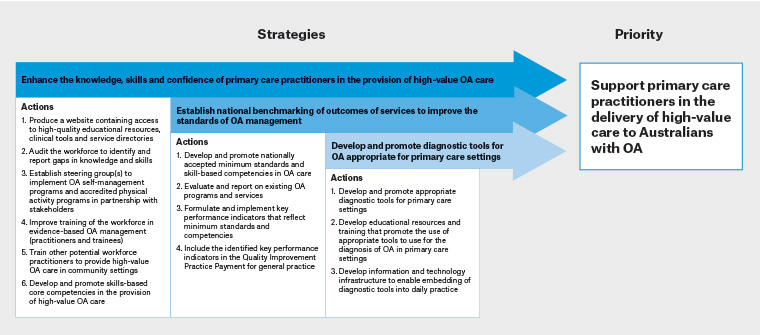

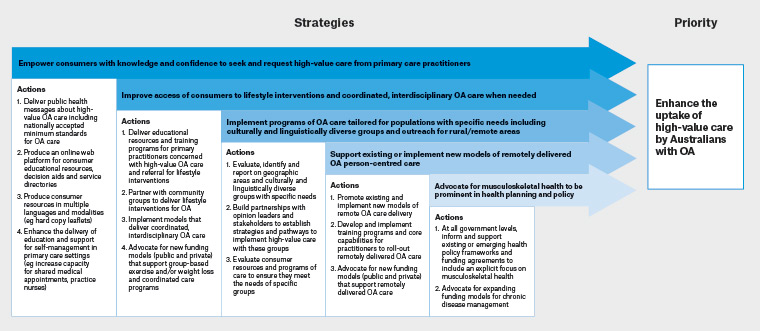

The Strategy was developed in consultation with a leadership group, thematic working groups, an implementation advisory committee, multisectoral stakeholders and the public. Two priorities were identified by the ‘living well with OA’ working group: 1) support primary care practitioners in the delivery of high-value care to Australians with OA, and 2) enhance the uptake of high-value care by Australians with OA. Evidence-informed strategies and implementation plans were developed through consultation to address these priorities.

This article is part two in a three-part series on the National Osteoarthritis Strategy.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common chronic joint disease globally: one in five Australians over the age of 45 years has OA.1 The National Osteoarthritis Strategy (the Strategy) aims to outline Australia’s national response to OA, covering three areas: ‘prevention’, ‘living well with OA’ and ‘advanced care’. Development of the Strategy is detailed in part one of the Strategy series.2 This article, part two, focuses on ‘living well with OA’.

The 2018 Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) guideline for the management of knee and hip OA recommends self-management, exercise and weight control (lifestyle interventions) for first-line care.3 Unfortunately, many Australians with OA do not receive ‘high-value care’, defined as treatment that is supported by evidence of benefit to patients, associated with a higher probability of benefit than harm, and costs that provide proportionally greater benefits than other treatments.4

Identified evidence–practice gaps

Underuse of lifestyle interventions and overuse of medications and imaging

Although general practitioners (GPs) describe favourable attitudes towards clinical practice guidelines, their familiarity with, and application of, OA management guidelines reveals an important implementation gap.5 The CareTrack study reported a median of 43% (95% confidence interval: 35.8, 50.5) of primary care–based healthcare encounters provided appropriate OA care.6 The Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) study reported that only 17% of patients who consulted their GP for hip/knee OA were referred for lifestyle interventions.7

Previous research into barriers to the use of lifestyle interventions found that primary care practitioners (GPs, nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists) feel underprepared to deliver these.8 Previous studies have identified a lack of confidence and knowledge of primary care practitioners to effectively deliver lifestyle interventions.9–12 Some practitioners continue to prescribe pharmacological agents7,13 with small therapeutic effects (eg paracetamol7,14) and/or with unsatisfactory risks of side effects (eg opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication7,13,15 and corticosteroid injections16). Also, despite recommendations for a limited role in the diagnosis of OA, there remains an overuse of unnecessary imaging.7 These evidence–practice gaps should be addressed by supporting practitioners with training and resources to enhance their knowledge, skills and confidence in the provision of high-value OA care.9–12 The RACGP offers continuing professional development courses on OA management for GPs and has published several OA entries in the Handbook of Non-Drug Interventions (HANDI) project.17

Important system- and service-level barriers to high-value OA care include inadequate consultation times; limited allied health networks for onward referral, particularly in regional areas; and inflexible funding models that inadequately support community-based care.9 The Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) provides a maximum of five face-to-face consultations per person with allied health per year, with no provision for addressing care disparities attributable to geography or case complexity. Improved access to effective lifestyle interventions would substantially improve outcomes.

OA guidelines recommend lifestyle interventions as a first-line treatment for OA.3 MBS Chronic Disease Management items and private health insurance should be accessed where appropriate. Hospital-based OA management programs available in some states, such as the Osteoarthritis Chronic Care Program18 in NSW and the Osteoarthritis Hip and Knee Service19 in Victoria, and the GLA:D Australia program is available through selected private physiotherapy clinics and some hospitals.20

Inadequate, inequitable uptake of high-value osteoarthritis care

Some Australians are dissatisfied with the care they receive for their arthritis, reporting poor access to health practitioners and information about possible treatments.21,22 These issues are amplified in rural/remote areas23 and among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.24,25 A potential strategy to address poor access to health services is the provision of remotely delivered healthcare. Although patients and practitioners are willing to embrace remotely delivered models for managing OA26–29 and there is evidence that telehealth is effective for managing musculoskeletal conditions,30,31 the opportunities for subsidised multidisciplinary telehealth services are limited. Establishing new, outcomes-based funding models involving Primary Health Networks in partnerships with private health insurers, local hospital networks and private providers for delivery of high-value face-to-face and digitally enabled OA care is vital to improving access. For example, Healthy Weight for Life is an existing remotely-delivered OA management program funded by some health insurers.32

Where high-value care is accessible, there is often a lack of uptake of lifestyle interventions by people with OA.33 Common misconceptions of people with OA include: OA is caused by ‘wear and tear’, their affected joint is ‘bone on bone’ and will inevitably deteriorate, activity may cause further joint ‘damage’ and lifestyle interventions have limited effectiveness.34 It is important for primary care practitioners to address misconceptions of patients as part of the overarching strategy to improve the uptake of high-value care by Australians with OA.

Priorities and strategic responses

The evidence–practice gaps identified in the literature informed the determination of two national priorities for the ‘living well with OA’ working group. Actionable strategic responses to tackle these priorities are proposed (Figures 1 and 2). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)35 was adapted to generate these figures. The full National Osteoarthritis Strategy provides detailed implementation plans for each strategy (https://ibjr.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/National-Osteoarthritis-Strategy.pdf). By following the relevant recommendations proposed in the Strategy, healthcare providers can ensure the provision of appropriate care for people with OA.

Figure 1. Strategic responses proposed to address priority 1. Click here to enlarge

OA, osteoarthritis

Figure adapted from Wolk et al36 and based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research37

Figure 2. Strategic responses proposed to address priority 2. Click here to enlarge

OA, osteoarthritis

Figure adapted from Wolk et al36 and based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research37