General practitioners (GPs) are the main providers of healthcare to Australian children and adolescents.1 According to the 2011 Australian Burden of Disease Study, mental health and behavioural problems, such as anxiety, depression and autism, represent an increasing burden of disease for Australian children and adolescents,2 and thus a higher proportion of GPs’ workload.3,4 Additionally, there is a growing acknowledgement of the role GPs can have in identifying and managing childhood developmental and psychological conditions.5,6 It is therefore concerning that literature from Australia and other developed countries has suggested that general practice registrars lack confidence in managing these conditions.7,8

In Australia, two colleges set the requirements for vocational GP registration: The Royal Australian College of General Practice (RACGP) and the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM).9,10 This study focused on the RACGP, with which 93% of Australian general practice registrars were training as of 2017 and in which there are a significant number of rural members.9,11 The RACGP requires registrars to have undertaken sufficient prevocational paediatric training prior to the first general practice–based training term. Sufficient prevocational paediatric training is defined as being able to identify and manage emergency, acute and chronic paediatric conditions.12 General practice registrars undertake either three or four full-time equivalent (FTE) general practice terms (GPT1–4; one term is 26 weeks FTE).13 Accredited Regional Training Organisations (RTOs) administer training according to RACGP standards, including prevocational paediatric requirements, and provide formal paediatric teaching.12

Research internationally and nationally has raised concerns about general practice registrar confidence in paediatrics.8,14 All current Australian research has been derived from secondary data analysis of the Registrar Clinical Encounters in Training (ReCEnT) project, which is an educational/research exercise documenting Australian general practice registrar consultations since 2010.15 From this dataset, previous studies report only indirect measures of registrar confidence, such as higher rates of referrals for paediatric than for adult patients.7,16,17

This study aimed to address the evidence gap by examining general practice registrars’ self-reported confidence in delivering paediatric care in general practice overall, by age group of the presenting patient and across different paediatric presentations; and determining whether type of prevocational paediatric experience was associated with participants’ level of confidence in delivering paediatric care in general practice. The findings are important for the bodies responsible for general practice registrar training.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was undertaken using an online survey of Australian general practice registrars, asking them about their level of confidence in managing paediatric patients in general practice (Appendix 1). The development of online survey items was informed by key themes and gaps identified in a literature review and reviewed by co-authors including regional training providers (NS, AS), a paediatrician researcher (HH) and general practice researchers (LS, PM, MTS). The questionnaire was piloted with academic general practice registrars at the University of Melbourne Department of General Practice, and was subsequently refined.

Data collection and participants

Quantitative data were collected using the online, study-designed survey in April/May 2017 using the SurveyMonkey program.18 Survey items included demographic information and prevocational paediatric training experiences. Five-point Likert scales were used to rate confidence with: paediatrics ‘overall’, different age groups within the paediatric age group, and when compared with other age groups of patients, in addition to confidence with various types of paediatric presentations. Likert scales measuring confidence were labelled as ‘1 = Very low confidence’, ‘2 = Low confidence’, ‘3 = Neutral’, ‘4 = Confident’ and ‘5 = Very confident’. The paediatric conditions for which participants rated their level of confidence in managing were selected for their relevance to general practice registrar training and prior exploration in the international literature and the ReCEnT project.8,17

Recruitment was undertaken with the support of the two Victorian RTOs: Eastern Victoria GP Training (EVGPT) and Murray City Country Coast GP Training (MCCCGPT). Only RACGP registrars were included. ACRRM registrars were excluded as the timing of their paediatric experience is variable.9,10 All 530 general practice registrars were sent a survey link by email. Registrars were assigned a unique code, which was recorded separately from their name and inserted with survey responses to allow removal of duplicates. The researcher could not break the code, and the training organisations had no access to the responses; thus confidentiality was maintained. Email reminders were distributed approximately weekly for six consecutive weeks.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC 15.19 The general practice training stages were defined as early (GPT1 and 2) and later (GPT3 and 4+) stages of training. Self-reported confidence levels overall, the different age groups and types of paediatric presentations were reported as counts and percentages. Cross tabulation and Fisher’s exact test were used to examine the association between overall confidence in managing paediatric patients in the primary care setting and each of the registrars’ exposure to general practice training stage (early versus late), age and types of prevocational training experience.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Melbourne (ID: 1648086.1).

Results

The survey response rate was 40.9% (217/530). Table 1 shows that the demographic characteristics of survey respondents were equally split between the training organisations and comparable to a recent national sample.11 Table 2 shows that the most common paediatric training experience was in a general hospital emergency department, completed by 91% of surveyed registrars, characterised by a variable frequency of paediatric patients seen during that rotation. Thirty per cent of registrars had completed any form of prevocational community- or primary care–based paediatric experience. An overlap in the types of experiences completed is noted.

| Table 1. Demographic characteristics of registrars who participated in the survey and interviews (survey n = 217; interview n = 10) |

| |

Surveys (n = 217) |

Interviews (n = 10) |

| |

n (%) |

n |

| Training organisation |

| EVGPT |

110 (50.5) |

6 |

| MCCCGPT |

108 (49.5) |

4 |

| Current general practice training stage |

| GPT1 |

109 (50.2) |

2 |

| GPT2 |

16 (7.4) |

1 |

| GPT3 |

74 (34.1) |

4 |

| GPT4 |

17 (7.8) |

3 |

| ARST |

1 (0.5) |

0 |

| Current training location |

| Rural |

101 (46.5) |

4 |

| Metropolitan |

116 (53.5) |

6 |

| Gender |

| Male |

81 (37.3) |

4 |

| Female |

136 (62.7) |

6 |

| Other |

0 |

0 |

| Age in years |

| <25 |

0 |

0 |

| 25–30 |

106 (49.3) |

8 |

| 31–35 |

62 (28.8) |

2 |

| 36–40 |

23 (10.7) |

0 |

| 41–45 |

15 (7.0) |

0 |

| >45 |

9 (4.2) |

0 |

| Country of medical training |

| Australia |

181 (83.4) |

10 |

| Overseas |

36 (16.6) |

0 |

| Confidence in managing paediatric patients |

| Confident |

– |

6 |

| Low confidence |

– |

3 |

| Unknown |

– |

1 |

Note: Discrepancies in totals due to missing responses

ARST, advanced rural skills term; EVGPT; Eastern Victorian GP Training; GPT, general practice term; MCCCGPT, Murray City Country Coast GP Training |

More than 80% of registrars in the late stages of training reported feeling very confident or confident managing paediatric patients overall, compared with half who were in the early stages of training. At least two-thirds of the registrars reported that they completed at least one paediatric-specific rotation, with most completing a rotation in the general paediatric ward. A higher percentage of registrars with specific paediatric experience reported they felt confident in managing paediatric patients, compared with those with no specific experience (Table 2). Completion of a Diploma in Child Health, now known as the Sydney Child Health Program (SCHP),20 was also associated with greater levels of confidence in managing paediatric patients.

| Table 2. Self-reported overall level of confidence in managing paediatric patients by registrars’ stage of training, age and type of training experience (n = 197) |

| Patient characteristic |

Total number of participants |

Low confidence |

Neutral |

Confident |

Very confident |

|

| |

n |

(col %) |

n (row %) |

n (row %) |

n (row %) |

n (row %) |

P value* |

| Overall confidence |

197 |

(100) |

15 (7.6) |

56 (28.4) |

119 (60.4) |

7 (3.6) |

N/A |

| Stage of training |

| Early stage of training (GPT1 or 2) |

111 |

(56.3) |

15 (13.5) |

40 (36.0) |

54 (48.6) |

2 (1.8) |

<0.001 |

| Late stage of training (GPT3 or 4+) |

86 |

(43.7) |

0 (0) |

16 (18.6) |

65 (75.6) |

5 (5.8) |

| Registrar’s age in years |

| 25–30 |

95 |

(49.5) |

8 (8.4) |

33 (34.7) |

52 (54.7) |

2 (2.1) |

0.11 |

| ≥31 |

97 |

(50.5) |

7 (7.2) |

20 (20.6) |

65 (67.0) |

5 (5.2) |

| Type of training experience |

| Community or primary care† |

| No |

138 |

(70.1) |

15 (10.9) |

45 (32.6) |

74 (53.6) |

4 (2.9) |

0.001 |

| Yes |

59 |

(29.9) |

0 (0) |

11 (18.6) |

45 (76.3) |

3 (5.1) |

| Completed at least one paediatric-specific rotation‡ |

| No |

64 |

(32.5) |

4 (6.3) |

26 (40.6) |

34 (53.1) |

0 (0) |

0.02 |

| Yes |

133 |

(67.5) |

11 (8.3) |

30 (22.6) |

85 (63.9) |

7 (5.3) |

| General paediatric ward§ |

| No |

79 |

(40.1) |

5 (6.3) |

32 (40.5) |

42 (53.2) |

0 (0) |

0.004 |

| Yes |

118 |

(59.9) |

10 (8.5) |

24 (20.3) |

77 (65.3) |

7 (5.9) |

| Paediatric hospital emergency department |

| No |

175 |

(88.8) |

14 (8.0) |

53 (30.3) |

103 (58.9) |

5 (2.9) |

0.13 |

| Yes |

22 |

(11.2) |

1 (4.5) |

3 (13.6) |

16 (72.7) |

2 (9.1) |

| Paediatric hospital subspecialty rotation |

| No |

177 |

(89.8) |

14 (7.9) |

52 (29.4) |

106 (59.9) |

5 (2.8) |

0.3 |

| Yes |

20 |

(10.2) |

1 (5.0) |

4 (20.0) |

13 (65.0) |

2 (10.0) |

| General hospital emergency department‖ |

| No |

17 |

(8.6) |

3 (17.6) |

2 (11.8) |

12 (70.6) |

0 (0) |

0.17 |

| Yes |

180 |

(91.4) |

12 (6.7) |

54 (30.0) |

107 (59.4) |

7 (3.9) |

| Obstetrics# |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

116 |

(58.9) |

10 (8.6) |

37 (31.9) |

66 (56.9) |

3 (2.6) |

0.41 |

| Yes |

81 |

(41.1) |

5 (6.2) |

19 (23.5) |

53 (65.4) |

4 (4.9) |

| Diploma of Child Health |

| No |

121 |

(61.4) |

14 (11.6) |

35 (28.9) |

70 (57.9) |

2 (1.7) |

0.01 |

| Yes |

76 |

(38.6) |

1 (1.3) |

21 (27.6) |

49 (64.5) |

5 (6.6) |

*P value calculated using Fisher’s exact test

†At least one of the following: Prevocational General Practice Placement Program (PGPPP) refugee health service, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health service, community-based health service, specialised community-based primary care for children and adolescents

‡At least one of the following: General paediatric ward, paediatric emergency department (ED; in paediatric hospital or otherwise) and/or paediatric hospital subspecialty

§General hospital paediatric ward and/or general medicine rotation at paediatric hospital

‖At least one of the following: Paediatric hospital ED, general hospital with a designated paediatric ED, general hospital ED

#Completed an obstetrics term and/or Diploma of Obstetrics

Note: n = 197; 20 survey respondents who did not respond to the overall level of confidence question were excluded. Very low confidence is not shown in the table as none of the respondents selected this option for self-reported overall level of confidence in managing paediatric patients.

GPT, general practice term |

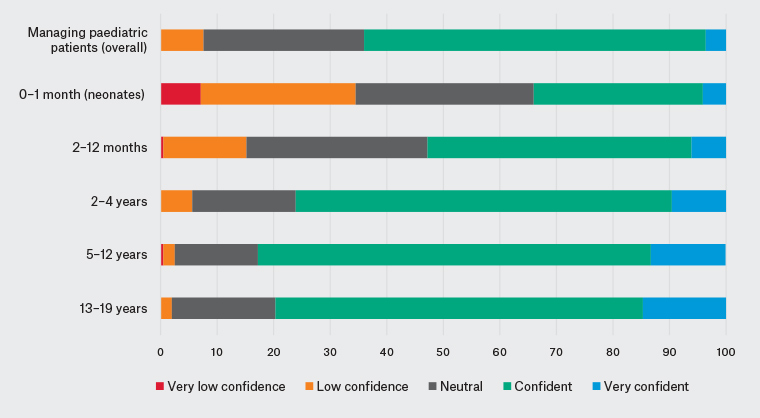

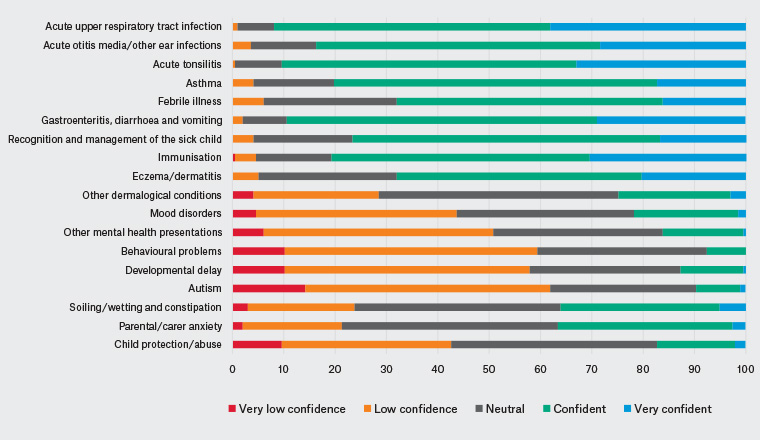

Table 3 summarises the respondents’ level of confidence in managing paediatric patients in general practice overall, patients presenting from different age groups (Figure 1) and patients presenting with a range of conditions (Figure 2). Almost two-thirds (126/197) of registrars stated they felt confident or very confident overall in managing paediatric patients. The majority of registrars reported feeling confident or very confident managing patients aged 2–19 years. In contrast, approximately 50% of the registrars reported feeling confident managing young children aged between two and 12 months, and approximately one-third of registrars felt confident managing neonates. Among the paediatric presentations, more registrars reported they had very low or low confidence in child protection or abuse; parental or carer anxiety; and mental health, developmental and behavioural issues. Conversely, they reported they felt confident or very confident managing paediatric immunisations and acute presentations such as upper respiratory tract infection, fevers or gastroenteritis.

| Table 3. Registrars’ self-rated levels of confidence to manage paediatric patients overall, patients of different age groups and paediatric presentations (n = 197) |

| |

Very low

confidence |

Low

confidence |

Neutral |

Confident |

Very

confident |

| |

n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

| Managing paediatric patients |

0 |

(0) |

15 |

(7.6) |

56 |

(28.4) |

119 |

(60.4) |

7 |

(3.6) |

| Age groups |

| 0–1 month (neonates) |

14 |

(7.1) |

54 |

(27.4) |

62 |

(31.5) |

59 |

(29.9) |

8 |

(4.1) |

| 2–12 months |

1 |

(0.5) |

29 |

(14.7) |

63 |

(32.0) |

92 |

(46.7) |

12 |

(6.1) |

| 2–4 years |

0 |

(0) |

11 |

(5.6) |

36 |

(18.3) |

131 |

(66.5) |

19 |

(9.6) |

| 5–12 years |

1 |

(0.5) |

4 |

(2.0) |

29 |

(14.7) |

137 |

(69.5) |

26 |

(13.2) |

| 13–19 years |

0 |

(0) |

4 |

(2.0) |

36 |

(18.3) |

128 |

(65.0) |

29 |

(14.7) |

| Paediatric presentations |

| Paediatric acute |

| Acute upper respiratory tract infection |

0 |

(0) |

2 |

(1.0) |

14 |

(7.1) |

106 |

(53.8) |

75 |

(38.1) |

| Acute otitis media/other ear infections |

0 |

(0) |

7 |

(3.6) |

25 |

(12.7) |

109 |

(55.3) |

56 |

(28.4) |

| Acute tonsillitis |

0 |

(0) |

1 |

(0.5) |

18 |

(9.1) |

113 |

(57.4) |

65 |

(33.0) |

| Asthma |

0 |

(0) |

8 |

(4.1) |

31 |

(15.7) |

124 |

(62.9) |

34 |

(17.3) |

| Febrile illness |

0 |

(0) |

12 |

(6.1) |

51 |

(25.9) |

102 |

(51.8) |

32 |

(16.2) |

| Gastroenteritis, diarrhoea and vomiting |

0 |

(0) |

4 |

(2.0) |

17 |

(8.6) |

119 |

(60.4) |

57 |

(28.9) |

| Recognition and management of the sick child |

0 |

(0) |

8 |

(4.1) |

38 |

(19.3) |

118 |

(59.9) |

33 |

(16.8) |

| Immunisation |

1 |

(0.5) |

8 |

(4.1) |

29 |

(14.7) |

99 |

(50.3) |

60 |

(30.5) |

| Paediatric dermatology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Eczema/dermatitis |

0 |

(0) |

10 |

(5.1) |

53 |

(26.9) |

94 |

(47.7) |

40 |

(20.3) |

| Other dermatological conditions |

8 |

(4.1) |

48 |

(24.4) |

92 |

(46.7) |

43 |

(21.8) |

6 |

(3.0) |

| Mental health, developmental and behavioural |

| Mood disorders |

9 |

(4.6) |

77 |

(39.1) |

68 |

(34.5) |

40 |

(20.3) |

3 |

(1.5) |

| Other mental health presentations |

12 |

(6.1) |

88 |

(44.7) |

65 |

(33.0) |

31 |

(15.7) |

1 |

(0.5) |

| Behavioural problems |

20 |

(10.2) |

97 |

(49.2) |

65 |

(33.0) |

15 |

(7.6) |

0 |

(0) |

| Developmental delay |

20 |

(10.2) |

94 |

(47.7) |

58 |

(29.4) |

24 |

(12.2) |

1 |

(0.5) |

| Autism |

28 |

(14.2) |

94 |

(47.7) |

56 |

(28.4) |

17 |

(8.6) |

2 |

(1.0) |

| Soiling/wetting and constipation |

6 |

(3.0) |

41 |

(20.8) |

79 |

(40.1) |

61 |

(31.0) |

10 |

(5.1) |

| Parental/carer anxiety |

4 |

(2.0) |

38 |

(19.3) |

83 |

(42.1) |

67 |

(34.0) |

5 |

(2.5) |

| Child protection/abuse |

19 |

(9.6) |

65 |

(33.0) |

79 |

(40.1) |

30 |

(15.2) |

4 |

(2.0) |

| Note: Discrepancies in total due to missing responses |

Figure 1. Victorian general practice registrars’ confidence by age group

Figure 2. Victorian general practice registrars’ confidence by paediatric presentation

Discussion

This is the first study of Australian general practice registrars’ views on their perceived level of confidence in managing paediatric patients in general practice. Importantly, this study showed that confidence levels are higher in registrars whose prevocational experience is paediatric-specific, rather than a general experience, and whose placement is in primary care, rather than a hospital. Completion of the Diploma of Child Health was also associated with a level of confidence in managing paediatric patients. This suggests that a paediatric-specific clinical immersion experience in a non-acute setting is an important component in the level of confidence in managing children in general practice.

The results show that level of confidence in managing paediatric patients varies with the nature of the paediatric presentation,7,17 with almost all registrars confident in managing acute presentations but having lower confidence with non-acute care including mental health and behavioural issues. Most registrars who responded to the survey completed hospital-based prevocational paediatric training, with fewer completing outpatient or community-based paediatric experience. Hence, with prevocational training skewed towards acute and emergency paediatrics, registrars have less exposure to, and are feeling less confident in, managing non-acute presentations.

To address this gap in paediatric experience and therefore registrars’ levels of confidence, alternative training needs to be considered. In Australia, there is substantial competition for paediatric hospital placements and a growing need to develop novel ways of gaining paediatric experience.16 Given the number of general practice registrars, and the demand from other paediatric specialties for paediatric outpatient or community placements, this will prove challenging.16 Allowing general practice registrars to attend private paediatric consults should be considered.21 Another option is further investigation of post-training models such as a recent GP–paediatrician integrated care model that has been shown to reduce GP referrals to the emergency department and reduce unnecessary investigations.22 Adjusting the curriculum may be another approach. However, such lecture-based resources may be insufficient to completely counteract the lack of practical experience.

Previous studies have suggested that higher referral rates for paediatric than adult patients to non-GP specialists or emergency departments indicate a lower level of general practice registrar confidence in managing paediatric presentations.17 However, it should be considered whether decisions to refer to the emergency department appeared clinically appropriate and, rather than being associated with a lack of confidence, may reflect appropriate caution in caring for a potentially sick child.

Strengths and limitations

As a result of time constraints, only registrars in semester one of the calendar year were recruited, precluding inclusion of trainees in semester two. Mitigating this was the inclusion of registrars of all levels of experience from basic to advanced terms. The survey response rate of 40.9% is in line with other general practice survey studies.23 The survey invitation was received by the entire general practice registrar population in the RACGP training program in Victoria, limiting selection bias. It is acknowledged that the findings may not be as generalisable to ACRRM registrars, and their inclusion could be considered in future research. Further research in other Australian states and territories would be required to ensure results are generalisable to all Australian registrars. This research is currently underway by the authors.

It is noted that interviews were also conducted with a subset of 10 registrars from the survey participants (Appendix 2). While it is not possible to present this data here, such qualitative information would elaborate further on the survey data and will be presented in future.

While it is important to consider registrar level of confidence in managing paediatric patients, it must be noted that self-assessment is complicated and, by its nature, cannot be entirely objective. Another alternative measure to consider is the concept of ‘competence’.24 In other studies of medical staff, assessment of confidence has not always correlated with observed competence.25 Measurement of competence would be practically difficult with this large number of participants. While not feasible to consider in this study, an assessment of competence could be considered as part of future investigation if novel types of paediatric experience were to be implemented.

Implications for general practice

This study has highlighted gaps in the preparation of Victorian general practice registrars to manage a range of common, non-acute, high-burden conditions affecting children and adolescents in Australia. Further research and investigation into training opportunities for future GPs is essential if primary care is to tackle the conditions that represent a growing disease burden for Australian children and adolescents. This potentially includes considering different models of training experience, such as outpatient or private paediatrician clinic placements. The next important stage for this research will be to collect similar data from general practice registrars nationally, comparing findings from registrars training in the different state-based methods of education and with ACRRM.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2