Pregnancy results in various physiological changes in the female body, including in the eyes. A typical pregnancy results in cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, hormonal and immunological changes. Hormonal changes occur, with a rise of oestrogen and progesterone levels to suppress the menstrual cycle.1

The eye, an end organ, undergoes changes during pregnancy. Some of these changes exacerbate pre-existing eye conditions, while other conditions manifest for the first time during pregnancy. Early recognition and understanding of management of ophthalmic conditions during pregnancy is crucial for the primary care physician. The aim of this article is to summarise the physiological and pathological ophthalmic changes that can occur during pregnancy (Table 1). A guide to the ophthalmic assessment of a pregnant woman presenting to general practice is also presented (Figure 1 and Table 2).

| Table 1. Ophthalmic associations in pregnancy |

| Physiological ocular changes in pregnancy |

Pathological pre-existing eye conditions worsening during pregnancy |

Pathological eye conditions occurring for the first time during pregnancy |

Pathological systemic pregnancy complications leading to eye conditions |

- Melasma

- Cornea thickness and curvature

- Myopic shift

|

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Glaucoma*

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- Meningiomas

|

- Central serous chorioretinopathy

- Uveal melanoma

|

- Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

- Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

- HELLP (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) syndrome

- Pituitary adenoma

- Thrombocytopenic purpura

- Grave’s disease

|

| *Pregnancy-related physiological changes may protect against glaucoma, with reduced intraocular pressure during pregnancy. |

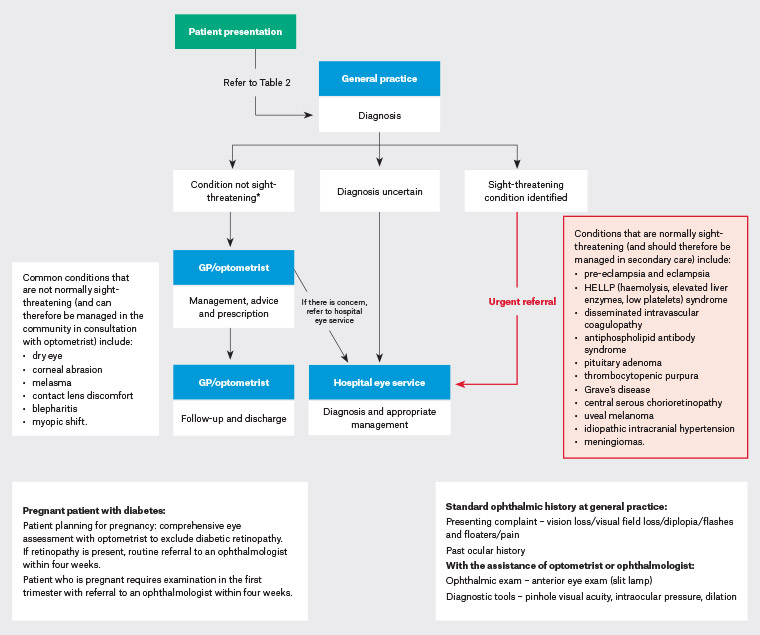

Figure 1. Ophthalmology: A diagnostic pathway for the pregnant patient12,48 Click here to enlarge.

*Ocular conditions that are deemed ‘not sight-threatening’ may worsen and progress to more severe manifestations that require specialist opinion.Pregnant patients who do not have a sight-threatening condition but have a known previous diagnosis can benefit from timely referral to their previous ophthalmologist and/or other subspecialist service.

GP, general practitioner

| Table 2. Vision change in a pregnant woman: A guide for patient symptomatology49,50 |

| Symptoms to guide urgency of referral to ophthalmologist |

Associated eye condition |

| Urgent |

| Transient vision loss (vision returns to normal <24 hours) |

Papilloedema, amarosis fugax |

| Sudden painless vision loss (>24 hours) |

Retinal artery or vein occlusion, serous retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, optic disc ischaemia |

| Sudden painful vision loss |

Acute angle closure glaucoma, optic disc neuritis (pain with eye movement in >50% of cases), intraocular infection |

| Sudden loss of visual field |

Optic neuritis, meningioma, branch retinal artery or vein occlusion, occipital lobe pathology, optic tract lesion, glaucoma |

| Diplopia monocular (symptom can be elicited from one eye only) |

Refractive error, cornea disease, iris pathology |

| Diplopia binocular (symptoms present when both eyes are open) |

Cranial nerve palsies – 3rd/4th/5th/6th |

| Intermediate urgency |

| Gradual painless loss of vision (over months or years) |

Refractive error, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy or associated diabetic macular oedema |

| Non-urgent |

| Burning/itching/tearing without pain |

Blepharitis, dry-eye syndrome, conjunctivitis, contact lens–related problems |

Physiological ocular changes in pregnancy

Physiological changes in pregnancy can affect various eye structures, including:

- Eyelids – melasma is a condition characterised by increased pigmentation around the eye and cheeks. It is commonly seen during pregnancy and results from increased melanocytosis and melanogenesis due to hormonal variation in pregnancy.2 It normally fades slowly after pregnancy and does not need active intervention.

- Cornea – corneal thickness, curvature and sensitivity may be altered during pregnancy. Corneal thickness and curvature can increase in pregnancy, especially in the second and third trimesters, and return to normal in the postpartum period.3 Patients who wear contact lenses may experience intolerance to the use of contact lenses. Pregnant women should be advised to delay obtaining a new prescription for glasses or undergoing a contact lens fitting until after delivery. Laser refractive surgery is contraindicated during pregnancy and is not recommended until stable postpartum refraction is achieved, because the majority of the cornea is made up of collagen in the stromal layer, which can be affected by pregnancy hormones. Corneal sensitivity can be reduced in pregnancy, and this in turn can increase susceptibility to serious corneal infections including post–laser surgery.4

- Lens – a myopic shift in the lens results from increased lens curvature in pregnancy, resulting in a change in refraction. Furthermore, a temporary loss of accommodation can be seen in the immediate postpartum period. These lenticular changes also indicate that new glasses or refractive surgeries should be avoided during pregnancy.

Pathological ocular changes in pregnancy

Pre-existing eye conditions modified during pregnancy

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy is a common ocular condition, and progression of diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy is seen in both types 1 and 2 diabetes, especially during the second and third trimesters (Figure 2). The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes is 14% during pregnancy.5 The degree of diabetic retinopathy at the start of pregnancy, glycosylated haemoglobin control, duration of diabetes and presence of hypertension are known risk factors for worsening of diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy.6,7 Regression of diabetic retinopathy and spontaneous recovery of vision often occur in the postpartum period. Gestational diabetes carries a very small risk (<1%) of developing retinopathy, and ophthalmologic examination is not necessary.8

An early discussion about pregnancy with patients who have diabetes may be advisable.9 Good prognostic factors include tight glycaemic control prior to conception and recent onset of diabetes at the time of pregnancy. Controlling risk factors such as blood sugar levels and hypertension is crucial for women with diabetes.10,11 Ocular examination is recommended before conception and again during the first trimester for women with diabetes. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) recommends referral to an ophthalmologist within four weeks of the initial ophthalmic exam.12 Diabetic macular oedema, a hallmark of severe diabetic retinopathy that leads to vision loss, may develop during pregnancy (Figure 2B). The safety of intravitreal anti–vascular endothelial growth factor treatment is not established and hence best avoided;13 intravitreal triamcinolone is a safe alternative. Crucially, eyes with existing or worsening diabetes sequalae such as non-clearing vitreous haemorrhage and tractional retinal detachments may be considered for surgical intervention.14

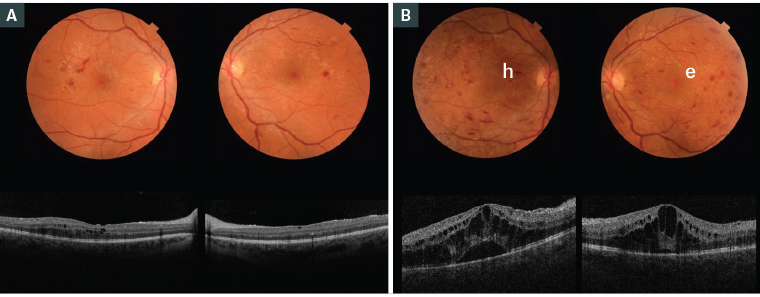

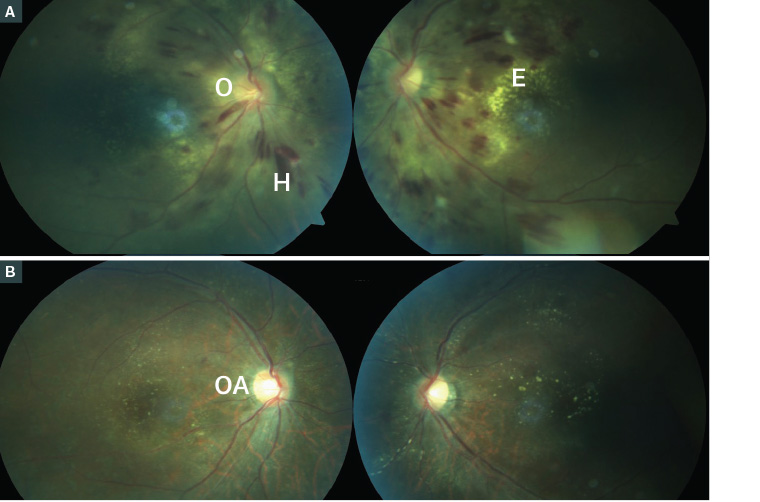

Figure 2. Fundus examination and optical coherence tomography imaging of a pregnant woman aged 22 years with type 2 diabetes

A. At 15 weeks’ gestation (visual acuity 6/18); B. At 20 weeks’ gestation showing worsening of diabetic retinopathy and macular oedema in both eyes (visual acuity 6/36; h – retinal haemorrhage; e – retinal exudates)

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a condition in which there is an elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), which can damage the optic nerve and cause visual field loss. Risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma include age, family history, previous trauma and myopia. Glaucoma may become more prevalent in women who are choosing to start families later, and may have pre-existing glaucoma while pregnant.

Physiological changes during pregnancy are protective against glaucoma. The level of female sex hormones during pregnancy also protects the optic nerve. These physiological effects and IOP return to baseline three months postpartum.15

In patients with pre-existing glaucoma, preconception counselling is important to assess the safety of IOP-lowering medication (Table 3). Laser trabeculoplasty is a safe option during pregnancy for refractive elevated IOP not controlled by medication or as an initial treatment option.16

| Table 3. Glaucoma medication in pregnancy51 |

| Class |

Medication |

Pregnancy class |

| Prostaglandin analogue |

Bimatoprost, latanoprost, tafluprost, travoprost |

B |

| Beta-blocker |

>Betaxolol, timolol |

C |

| Alpha-2 agonist |

Apraclonidine, brimonidine |

B |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor |

Brinzolamide, dorzolamide |

B |

| Cholinergic |

Pilocarpine |

B |

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) results from elevated intracranial pressure without a known cause of hydrocephalus or brain tumour with normal cerebral spinal fluid composition. The clinical presentation may include headaches, nausea, pulsatile tinnitus and obscuration of vision from papilledema (Figure 3). Pre-existing IIH can worsen during pregnancy as a result of additional weight gain. Lumbar puncture, under neurology physician supervision, is safe during pregnancy. Serial lumbar punctures may be performed to treat severe refractory disease to provide relief from headaches and vision loss.17 Acetazolamide is classed as pregnancy category B2 medication; however, a recent retrospective clinical study showed it is relatively safe for the management of IIH in pregnancy.18

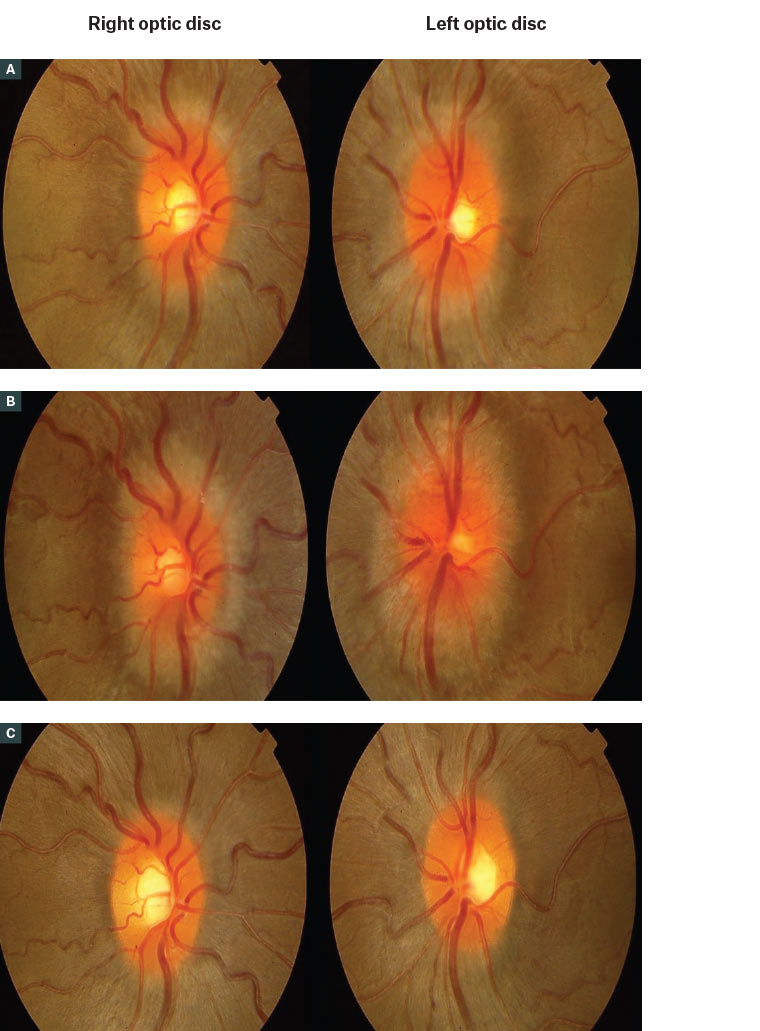

Figure 3. Serial fundus photographs of a patient with idiopathic intracranial hypertension

A. At baseline prior to conceiving, showing mild bilateral optic disc swelling; B. The disc’s swelling worsened during pregnancy in the second trimester, with increasing blurring of the disc margins; C. Swelling was managed with a lumbar puncture to lower the intracranial pressure, and the disc swelling improved post–lumbar puncture.

Meningioma

Although a typically slow-growing tumour, a meningioma can have accelerated growth in pregnancy because of increasing oestrogen and progesterone levels and vascular endothelial growth factors.19 The incidence of meningiomas during pregnancy is estimated at 5.6 cases in 100,000 pregnant women.20 A pre-existing sphenoid bone meningioma near the optic canal can result in compressive optic neuropathy. Pregnant patients with known meningiomas should have baseline visits with their neurosurgeons and neuro-ophthalmologists, with ongoing follow-up as per their specialists’ recommendations.21

Pathological conditions occurring for the first time in pregnancy

Central serous chorioretinopathy

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) is defined as a fluid-filled detachment of the neurosensory retina due to focal leakage at the retinal pigment epithelium level (Figure 4A). Symptoms can vary from halos and blurred vision to severe central vision metamorphopsia. Recent studies have shown an increased risk for CSCR during pregnancy due to increased cortisol levels and other hormonal variations in pregnant women.22 CSCR can occur in all trimesters of pregnancy and usually resolves postpartum without any treatment (Figure 4B).23 It can recur in subsequent pregnancies.24

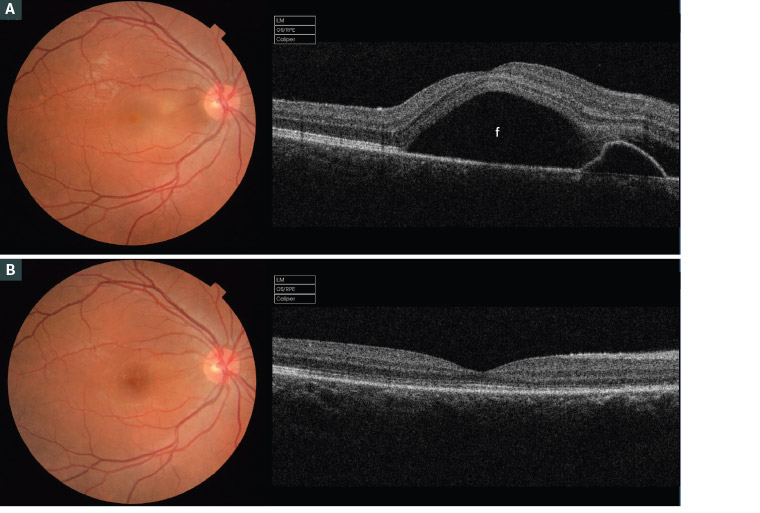

Figure 4. Fundus examination and optical coherence tomography imaging of a Caucasian woman aged 33 years during her second pregnancy

A. In her fifth month of gestation, showing central serous chorioretinopathy in her right eye; B. Spontaneous resolution of the subretinal fluid in the postpartum period

Uveal melanoma

There is a documented higher incidence of ocular melanoma and rapid progression in pregnant women, compared with non-pregnant women.25 The mechanism of tumour growth during pregnancy is unclear, as hormonal correlation with the pathophysiology of melanoma has not yet been established.26

Ophthalmic associations due to complications in pregnancy

The following conditions in pregnancy can be associated with visual symptoms. Management of these conditions includes a multidisciplinary approach with the general practitioner being the central point of contact.

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

The visual system is affected in approximately 25% of patients with pre-eclampsia and 50% of patients with eclampsia. Symptoms include blurred vision, visual field defects and diplopia.27 Pre-eclampsia causes severe arteriolar spasm due to vasospasm with increased resistance to blood flow and generalised constriction of retinal arterioles.28 The severity of retinopathy in patients with pre-eclampsia is inversely related to fetal birth weight.29

Fundus findings in pre-eclampsia may include retinal arteriole narrowing, tortuosity, retinal haemorrhage and optic nerve swelling (Figure 5A). Acute blindness in women with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia is often caused by serous retinal detachment or cortical blindness.30 Cortical blindness is described as acute blindness with normal fundoscopy findings and pupillary function. The pathophysiology of cortical blindness is attributed to vasoconstriction of vessels of posterior cerebral circulation. Most women with cortical blindness recover full sight postpartum, usually after 48–72 hours;31 residual retinal signs like Elschnig spots, pigment epithelium changes and optic atrophy may occur (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Coloured fundus photographs of a patient with pre-eclampsia

A. Bilateral retinal haemorrhage with both flame-shaped and blot haemorrhage (H) and lipid exudate (E), especially around the left macula and bilateral optic nerve swelling (O); B. Postpartum; the blood pressure was controlled and the retinal changes improved after five weeks, but the patient had residual right optic atrophy (OA) showing pallor of the optic nerve and residual exudates.

Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets

Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome is a severe variant of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Patients with HELLP syndrome can experience visual symptoms ranging from minor visual disturbances to acute visual loss. Contributing factors include retinal artery and vein occlusions, serous retinal detachments and Purtscher-like retinopathy causing severe permanent damage. The superimposing of HELLP on pre-eclampsia and eclampsia can lead to neurological damage in the form of occipital lobe infarction causing cortical blindness.32

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) is a major emergency in pregnancy. It is caused by the disruption of the coagulation pathway (intrinsic and extrinsic). Patients’ visual symptoms include blurred vision, visual field defects and metamorphopsia. End-organ damage results from the formation of small thrombi in small vessels; this can be generalised or localised in the body. Vision loss in DIC is either due to central choroidopathy or serous retinal detachment.33,34 Serous retinal detachment is highly suspected when DIC is secondary to pregnancy-related hypertension.35 The defining characteristic of these presentations is that they are always bilateral. Management aims to reverse the obstetric complication (eg abruptio placentae, retained fetus or sepsis).

Thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a haematological disorder that can occur during pregnancy. It is characterised by microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia, renal failure and neurological disturbances.36 Ocular features to note include arteriolar constriction, exudates, retinal haemorrhage and serous retinal detachment, which occur in approximately 10% of patients with TTP.37,38 When vessels supplying the optic nerve are thrombosed, it can result in optic nerve atrophy, and a cerebrovascular accident affecting the visual pathway may result in homonymous hemianopia.39,40

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune condition with the hallmark feature of thrombophilia in the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. As many as 14–18% of patients present with ocular symptoms.41 APS can manifest as conjunctival microaneurysms or telangiectasia, episcleritis, keratitis and iritis. Posterior segment manifestations include retinal detachment, posterior scleritis, vitritis and retinal arterial and vein thrombosis.42 Patients are treated with long-term anticoagulants, and the visual prognosis is good.43 It is imperative that the practitioner discusses the possibility of APS diagnosis with a rheumatologist or haematologist for ongoing multidisciplinary management.

Grave’s disease

Grave’s disease affects 1–2% of all pregnancies.44 The disease can worsen or occur de novo during the first trimester of pregnancy, in addition to high rates of recurrence postpartum. Grave’s orbitopathy affects 25% of all patients with Grave’s disease and can be a useful indicator during physical examination. Orbitopathy includes proptosis, lid lag, periorbital oedema, extraocular muscle enlargement and fibrosis, optic neuropathy and lacrimal gland dysfunction.45

Pituitary adenoma

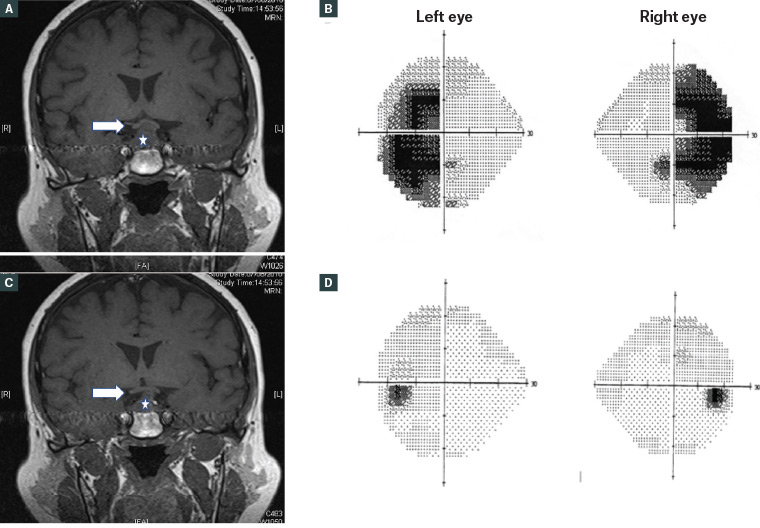

During pregnancy there is a physiological increase in the size of the anterior pituitary gland by, on average, 36% due to an increase in oestrogen levels and prolactin-secreting cells.46 Therefore, a previously undetected pituitary adenoma may manifest during pregnancy. Any pregnant woman who develops a headache, visual disturbances, visual field changes (especially bitemporal changes), decreased visual acuity and diplopia should be investigated thoroughly.47 Pregnant women with known pituitary adenomas should be managed by multidisciplinary teams involving an endocrinologist and neuro-ophthalmologist. These patients require a monthly visual field and visual acuity assessment and evaluation of the optic nerve. Most adenomas will regress following pregnancy, leaving no vision compromise postpartum (Figure 6).27

Figure 6. Coronal magnetic resonance imaging scan and visual field study of a patient with a pituitary adenoma during pregnancy

A. Pituitary adenoma (star) enlarged during pregnancy and abutting the optic chiasm from below (arrow); B. The resulting bitemporal hemianopia; C. Postpartum, the adenoma regressed in size and was not compressing the chiasma (arrow); D. The bitemporal hemianopia resolved postpartum.

Conclusion

Physiological ophthalmic manifestations are common in pregnancy and may account for the majority of patients’ visual symptoms; such physiological changes can be managed in the community by general practitioners and optometrists. Pregnant patients with pre-existing eye conditions can be referred to their ophthalmologists for monitoring during pregnancy to avoid deterioration. Women with systemic conditions such as HELLP syndrome, DIC and eclampsia will require interdisciplinary specialty management in a hospital with an antenatal service.