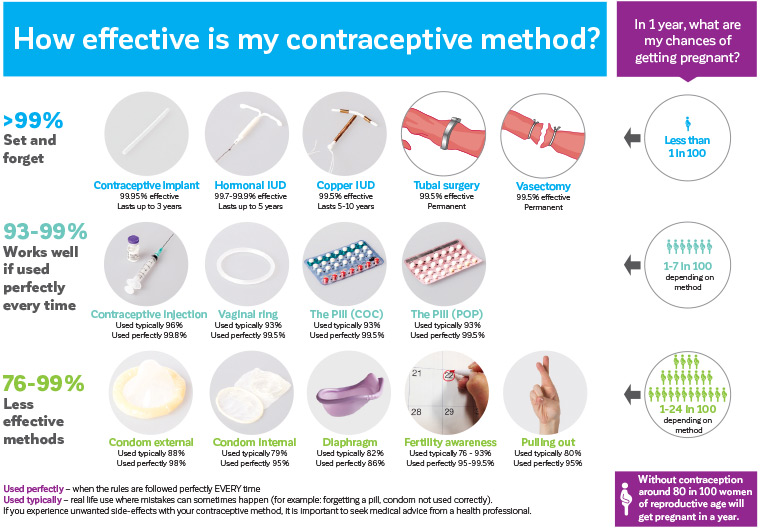

Increasing access to long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) is key to reducing rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion.1,2 LARCs, including hormonal and copper-bearing intrauterine devices (IUDs) and the contraceptive implant, provide highly effective ‘set-and-forget’ contraception, which are suitable for provision in general practice.3 They have very few contraindications and can be recommended as first-line contraceptive options across the reproductive lifespan, from adolescence to perimenopause.4 The Family Planning Alliance Australia contraceptive efficacy card is a useful tool to support informed decision making when discussing contraceptive options with patients (Figure 1).5 In Australia, uptake of LARCs has been increasing, with Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) claims for hormonal IUDs and implants almost doubling between 2006 and 2018, and Medicare Benefits Schedule data indicating a more than three-fold increase in IUD insertion procedures for people aged 15–24 years in the past 10 years.6,7 A recent survey also estimated that 10.8% of women aged 15–44 years were using a LARC.8 The recently completed Australian Contraceptive ChOice pRoject showed that a combination of training doctors in providing LARC information and rapid access to LARC insertion clinics increases LARC uptake.9

Figure 1. Family Planning Alliance Australia contraceptive efficacy card. Click here to enlarge

Reproduced with permission from Family Planning Alliance Australia, How effective is my contraceptive method? Hamilton Valley, NSW: FPAA, 2020.

The UK Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) recommends extended use of LARC methods during the COVID-19 pandemic, as access to clinical services for removal/replacement were limited in the UK.10 In Australia, where access has generally been maintained, removal/replacement according to current eTG guidelines is recommended, with case-by-case shared decision making with the patient when access to LARC insertion is limited.4,11 This article summarises the most recent updates to guidelines and practical recommendations concerning LARC use.

Intrauterine device update

IUDs include non-hormonal copper IUDs and the hormonal levonorgestrel (LNG) IUD. Recent developments have seen the introduction of a new PBS-listed LNG IUD in early 2020, updated recommendations regarding use of IUDs at perimenopause and advice regarding the use of menstrual cups with IUDs.

Copper IUDs are effective immediately after insertion.12 Copper IUDs are not PBS-listed, generally costing $70–$100. They last 5–10 years, depending on the type. They might make menstrual bleeding heavier and more prolonged, which can limit their use for some patients.13,14

Copper IUDs can be used as post-coital emergency contraception when inserted within five days of unprotected sexual intercourse and after excluding risk of an earlier established pregnancy.15 If all episodes of intercourse in the cycle were in the past five days, the copper IUD can be inserted regardless of when it is in the cycle. If unprotected intercourse occurred earlier than five days prior to copper IUD insertion, to ensure insertion of the copper IUD occurs before implantation of an early pregnancy, conservative advice is that it should be inserted by day 12 of the cycle.

In contrast, hormonal IUDs are only immediately effective if inserted between days one and five of the menstrual cycle, otherwise they require seven days to become effective. For more than 15 years, the 52 mg LNG IUD (Mirena) had been the only hormonal IUD available in Australia. However, a smaller, lower-dose 19.5 mg LNG IUD (Kyleena) was listed on the PBS in March 2020. Table 1 compares these two hormonal IUDs. The insertion technique is identical for both devices, and both are licensed for up to five years of use.16,17 Kyleena insertion might be easier and associated with less discomfort than Mirena, given the smaller insertion tube and device dimensions.18 As a result, Kyleena could be a suitable option for people with a relatively small cervical canal and/or uterine cavity, including nulliparous and younger people.19 While both devices can be associated with initial irregular bleeding, trial data suggest that Kyleena could be associated with a slightly higher average number of bleeding/spotting days and lower rates of amenorrhoea compared with Mirena.18 Most other hormonally related side effects appear similar between Mirena and Kyleena, including acne, breast discomfort and weight gain, although Kyleena is associated with a reduced risk of benign functional ovarian cysts compared with Mirena.18 As a result of its lower hormone dose, Kyleena, unlike Mirena, is not licensed either for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding or for endometrial protection with menopause hormone therapy (MHT) and is not recommended for extended use from the age of 45 years.16,17,20 A recent randomised trial indicated that Mirena could provide effective emergency contraception; however, due to data limitations, it cannot be recommended in this situation.21,22

| Table 1. Comparison of hormonal intrauterine devices available in Australia |

| |

19.5 mg LNG IUD (Kyleena) |

52 mg LNG IUD (Mirena) |

| Indications |

Contraception |

Contraception

HMB

MHT |

| Duration of use |

5 years |

5 years |

| Effectiveness |

99.7%33 |

99.9%34 |

Approximate IUD cost

Additional costs often apply for the insertion and removal procedures, which can vary between practices |

PBS: Approximately $6.80 with healthcare card or $42.50 without

Approximately $170 on private prescription |

PBS: Approximately $6.80 with healthcare card or $42.50 without

Approximately $213 on private prescription |

| Serum LNG levels at 90 days35 |

~140 ng/L |

~280 ng/L |

| Device dimensions (width × height, mm) |

28 mm × 30 mm |

32 mm × 32 mm |

| Insertion tube |

3.8 mm |

4.4 mm |

| Visible on ultrasound and X-ray |

Yes (with silver ring on stem to distinguish it from Mirena) |

Yes |

| Discomfort during insertion procedure18 |

In a study where people reported pain levels during insertion of both IUDs, pain with insertion was rated as either none or mild by the majority. However, some reported higher levels of pain during Mirena insertion than with Kyleena |

| Changes to bleeding patterns18 |

There can be increased bleeding and spotting days in the first 6 months of use with both IUDs. By 3 years of use, most people have fewer than 4 bleeding or spotting days/month. There are slightly fewer bleeding and spotting days per month with Mirena compared with Kyleena |

| Rate of amenorrhoea36 |

12.3% at 1 year

23% at 5 years |

18.6% at 1 year

30–40% at 5 years |

| Use for HMB |

Can assist with management of heavy periods, but was not specifically studied in this population |

Licensed for HMB. Bleeding reduction of ~85%37 |

| Use for dysmenorrhoea |

In a study, the baseline number of people with no period pain at the start of the study was 50%. This improved to 80% in users of both IUDs at 3 years18 |

| Use for endometriosis or adenomyosis |

Not specifically studied in this population |

Improves endometriosis and adenomyosis, and decreases pain38–43 |

| Side effects |

Insufficient evidence to indicate whether lower systemic hormone exposure with Kyleena is associated with fewer hormonal side effects compared with Mirena18,35

Hormonal side effects with both IUDs can include headache, acne, breast tenderness, mood changes and irregular bleeding

If these occur, most will resolve with continued use of the IUDs |

| How common are ectopic pregnancies on the IUD? |

If pregnancy occurs with a hormonal IUD, about half of those pregnancies will be ectopic (outside the uterus).33,34 However, because IUDs are so effective at preventing pregnancy, IUD users are less likely to have an ectopic pregnancy while they have an IUD than when they do not have an IUD |

| HMB, heavy menstrual bleeding; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel; MHT, menopausal hormone therapy; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme |

As patients approach menopause, expert opinion supports extended off-label contraceptive use of the Mirena and copper IUDs. This reflects lower fertility at this life stage and removes the risks associated with removal and reinsertion. Note that the Kyleena is not recommended for extended use. Table 2 summarises these recommendations. Menopause is a clinical diagnosis, after which time contraception is no longer required. For people not using hormonal contraception, it is diagnosed after 12 months of amenorrhoea after turning 50 years of age, or following 24 months amenorrhoea in those aged below 50 years. Diagnosis of menopause is complicated when using hormonal contraception because the hormones themselves can result in amenorrhoea, which is indistinguishable from the natural cessation of menses. For patients using an LNG IUD, contraceptive implant or progestogen-only pills who have been amenorrhoeic for at least 12 months since turning 50, updated guidance recommends that a single-serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) level can be used to determine the need for ongoing contraception. If FSH is >30 IU/L, contraception is only required for one more year. If FSH is ≤30 IU/L, contraception is still required, and the FSH can be rechecked in a further year if required. Alternatively, patients can continue their progestogen-only method of contraception, provided they remain medically eligible, until the age of 55 years, after which the risk of conception is negligible.20 Further information and a flowchart for contraception use from 50 years of age is available from Sexual Health Victoria (formerly Family Planning Victoria; https://shvic.org.au/assets/img/content/SHV_ContraceptionWomenOver40.pdf).

| Table 2. Off-label extended contraceptive use of intrauterine devices in perimenopause |

| Hormonal IUDs |

Copper IUDs |

| 19.5 mg LNG IUD (Kyleena) |

52 mg LNG IUD (Mirena) |

TT380 Standard, TT380 Short and Load 370 |

| Extended use not recommended |

If inserted aged ≥45 years, can be used for contraception until menopause or aged 55 years12 |

If inserted aged ≥40 years, can be used for contraception until menopause or aged 55 years18 |

| IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel |

It should be noted that when Mirena is used to protect the endometrium as part of an MHT regimen, it should be replaced at five years. Extended use beyond five years for this indication is not advised. No other progestogen-only contraceptives are licensed for endometrial protection and cannot be used as part of an MHT regimen. However, they could be used alongside MHT for patients requiring contraception.20,23

The increasing popularity of menstrual cups and IUDs has prompted consideration of whether there is increased risk of IUD expulsion or dislodgement with their simultaneous use. It has been postulated that this could occur through either a suction effect or accidental pulling on the IUD threads.24 However, there is currently limited and conflicting findings regarding this risk, and whether it is more likely in the first weeks after IUD insertion or is equally possible throughout the duration of use.25 For patients using a menstrual cup with an IUD, provide advice on how to check their IUD threads after menses and how to gently release the suction before cup removal to avoid the threads getting caught between the cup and vaginal wall.25,26 General practitioners (GPs) should encourage patients to attend for review if the IUD threads cannot be felt or there is concern the IUD has moved. Medical review includes a speculum examination to look for visible IUD threads, a urine pregnancy test to exclude pregnancy and pelvic ultrasound +/– X-ray if threads are not visible. Oral emergency contraception might also be offered depending on history.

Implant update

The etonogestrel single-rod contraceptive implant provides highly effective (99.95%) contraception for up to three years.5 There is no need to replace the implant earlier than three yearly for overweight/obese individuals due to lack of evidence of increased pregnancy risk.27 Troublesome bleeding is the most common side effect leading to discontinuation of the implant. It is helpful to explain the range of expected vaginal bleeding, which is: one in five users have amenorrhoea; three in five users have infrequent, irregular bleeding; and one in five users have frequent or prolonged bleeding. Approximately half of those with frequent prolonged bleeding will improve after three months. Family Planning Alliance Australia recommend a proactive approach to actively encourage patients to return for review of troublesome bleeding, with guidance on management offered in an online resource (www.familyplanningallianceaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/fpaa_guidance_for_bleeding_on_progestogen_only_larc1.pdf).

In 2011, the applicator was improved to facilitate superficial insertion and reduce the risk of the implant falling out, and the implant was changed to be radiopaque.28

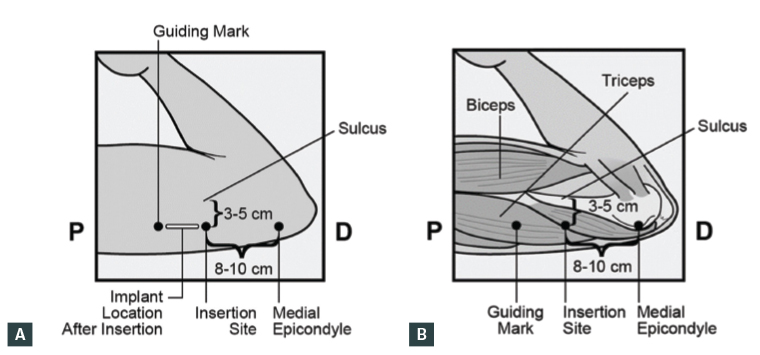

Recently, there have been updates to the recommended insertion site following a small number of case reports of nerve injuries or intravascular insertion.29 The new recommended site for insertion was informed by a study of 40 female cadaver arms, in which no major neurovascular structures were identified in the area 8–10 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 3–5 cm posterior to the sulcus, suggesting this window is theoretically safer than other areas of the arm. Further, the ulnar nerve was displaced away from this window with elbow flexion and the hand underneath the head.30

The Australian product information for Implanon NXT was updated to reflect these findings in January 2020.31 A summary of the new recommendations is listed in Box 1 and Figure 2. In addition to these new recommendations, the following clinical guidance about implant removals and reinsertions is provided:

- Replacement (removal and re-insertion) site: If the patient is not experiencing any issues, it is not necessary to remove implants before they are due for replacement (even if inserted before this updated placement advice). When due for removal and replacement, the new implant could be inserted in the same arm and through the same incision if the previous implant was in the currently recommended position. Otherwise, re-site the new implant according to the updated product information (Box 1); it is important to advise the patient of the rationale for this changed position and that they will have two small puncture wounds, rather than one.

- Removal of non-palpable implants: It is important not to attempt removal of impalpable implants. Consider pregnancy test and additional contraception (if required), check the previous insertion site (and arm), arrange local imaging (X-ray and/or ultrasonography) and removal under ultrasonography guidance, if possible. If the implant cannot be found in the arm, consider chest X-ray, as rare events of migration to the pulmonary vessels have been reported. Serum etonogestrel levels could be measured in consultation with the manufacturer.

| Box 1. Key implant updates |

- Patient positioning: The patient’s arm should be flexed at the elbow with the hand underneath the head (or as close as possible).

- Insertion site: 8–10 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 3–5 cm posterior to the bicipital groove (this is the sulcus between biceps and triceps muscles) in the non-dominant arm. This means that the implant will be inserted subdermally (superficially) under the skin, over the triceps muscle. Measure and mark the insertion site. If it is not possible to insert the implant 3–5 cm from the sulcus (eg a person with thin arms), it should be inserted as far from the sulcus as practical.

|

Figure 2 A. Surface anatomy location of Implanon NXT; B. Anatomical location of Implanon NXT

Figure 2 A. Surface anatomy location of Implanon NXT; B. Anatomical location of Implanon NXT

Reproduced with permission from Merck Sharp & Dohme BV, a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

Videos demonstrating the correct procedure techniques are available online (www.implanonnxtvideos.com).

Superficial insertion remains crucial to safe insertion technique. It is important to be able to visualise the needle throughout the insertion procedure and to lift or ‘tent’ the skin while the needle is being inserted in the horizontal direction into the subdermal plane.32

Before attempting implant removals, always check that the implant is palpable and superficial. When downwards pressure is applied to the proximal end, the distal end should ‘pop up’ from under the skin. The small incision for removal should be made at the distal tip, with the scalpel blade parallel to the direction of the implant. For implants inserted overseas (such as New Zealand), take a careful history and check for multiple implant contraceptives, such as the two-rod implant, Jadelle, licensed for five years, and Sino-implant, licensed for four years.

Long-acting reversible contraceptive training

IUD insertion training

IUD training includes theoretical learning and supervised insertions in a clinical setting and is available through state or territory family planning organisations, some IUD-inserting GP educators, gynaecologists and hospitals.

Implant insertion training

It continues to be recommended that only professionals who have undergone training perform implant procedures. Training includes both theoretical learning and simulation practice on a model arm. Several training organisations have made Implanon NXT simulation training available via video link, improving access. Training courses are available through most general practice registrar organisations, some hospitals and through state or territory family planning organisations.

Conclusion

To reduce unintended pregnancies and facilitate informed contraceptive choice, general practice plays a key role in providing access to LARCs. The new lower-dose, slightly smaller hormonal IUD offers an additional contraceptive choice that is likely to be valued by users, particularly younger people. New guidance on use of IUDs in perimenopause and with concomitant use of menstrual cups, as well as changes to implant insertion recommendations, assist safe LARC provision. Incorporating these updated practice points into the clinical care of patients will support continuing improvement in LARC uptake within the context of informed shared decision making.

Key points

- LARCs, including IUDs and the implant, provide the most effective methods of reversible contraception, and are a key strategy to reduce unintended pregnancies.

- The recently PBS-listed 19.5 mg levonorgestrel hormonal IUD (Kyleena), which is licensed for five years of contraceptive use, offers a lower-dose option with a slightly smaller frame compared with the 52 mg levonorgestrel hormonal IUD (Mirena).

- Expert opinion and guidance support have extended the off-label use of copper IUDs from 40 years of age and the 52 mg hormonal IUD (Mirena) from 45 years of age for contraception.

- Simultaneous use of menstrual cups and IUDs potentially poses an increased risk of expulsion or dislodgement of the IUD, requiring advice to users.

- The contraceptive implant insertion site is now recommended at 8–10 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 3–5 cm posterior to the bicipital groove (this is the sulcus between biceps and triceps muscles) in the non-dominant arm.

Resources