Button battery ingestion (BBI) and insertions are unique foreign body emergencies that require timely removal as they result in rapid tissue injury to surrounding structures including the oesophagus, ear, nose or vaginal orifices. General practitioners (GPs) may be consulted for advice when parents suspect BBI or when their children present with respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms that may represent an underlying button battery impaction.1 Approximately 200 children per year are potentially exposed to button battery injury in Australia, with at least a dozen per year experiencing severe injury. Since 2013, there have been three deaths from oesophageal button battery injury.2–4 Legislative changes regarding the storage and sales of button batteries came into effect from December 2020, requiring compliance by June 2022.5 This article will discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, presentation and updated management of button battery injury in the paediatric population.

Epidemiology

Button battery injury is typically reported in children aged 14–36 months, with a median age of 23 months, related to a child’s developmental phase of placing objects in their mouth and other orifices.6,7 This age group presents a challenge as they are unable to reliably report what they have eaten without supervision. Cases have also been reported in older individuals with mental health conditions, self-harm intent, intellectual impairment and dementia. The incidence of button battery injury is marginally higher in males when compared with females.6,8,9

Lithium button batteries are favoured commercially because of their compact size, high voltage and long shelf life, and this is reflected by a six- to sevenfold increase in BBI since their introduction in the late 1970s.10 The source of the button battery is unknown in the majority of cases .6 Most authorities agree that button battery injury is avoidable as the batteries are typically obtained from unsecured toys, hearing aids, watches, remote controls and car key remotes.6,8,10 Until the December 2020 legislative change, regulations for secured use of button batteries in toys applied only for those designed for children aged <36 months.5 This still allowed younger siblings access to unsecured button batteries in an older sibling’s toy and common household and medical equipment (eg thermometers, glucometers).5 A lack of recognition of the urgency of surgical removal by medical staff, incorrect triaging or advice, and requests for imaging at local radiology facilities while tertiary hospital care was available are a few examples of avoidable delays to definitive management of button battery injury.8,11

Pathophysiology

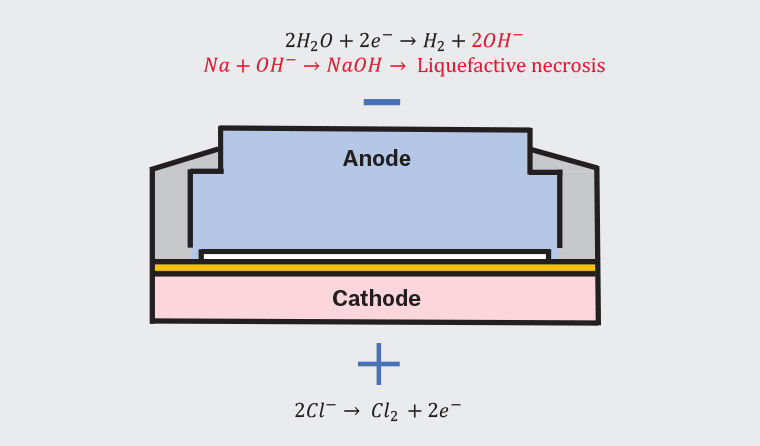

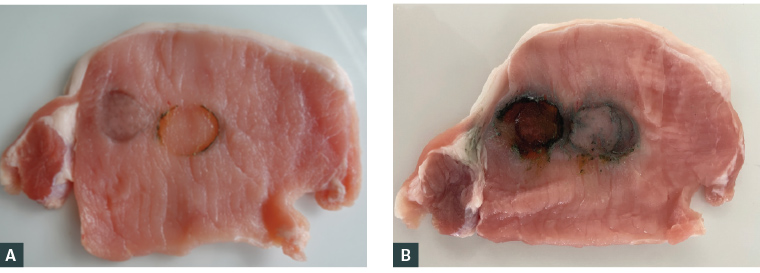

Button battery injury occurs predominantly by liquefactive necrosis, with pressure necrosis and leakage of contents playing a lesser role. The tissues abutting the button battery complete an electrical circuit. This results in significant injury on the anode face (small side) due to generation of hydroxide, resulting in liquefactive necrosis (Figure 1).12 Tissue injury has been demonstrated in as little as 15 minutes of exposure (Figure 2A), with potential for perforation in two hours.13 This can rapidly progress to ulceration, perforation and formation of fistula.13,14 Oesophageal button battery impaction can be life threatening. The upper third of the oesophagus abutting the cricopharyngeus muscle, the mid oesophagus abutting the left mainstem bronchus with the aortic arch, and the lower oesophageal sphincter at the level of the diaphragm are the main locations of impaction.15,16 Injury can progress post removal of button battery, with cases of delayed oesophageal perforation and fistula identified in the literature.1

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of button battery injury

Figure 2. Button battery exposure on pork with a new lithium 3 V button battery, 20 mm

A. 15 minutes of exposure; B. Two hours of exposure

Severity of injury depends on several factors including type of metal, size, voltage, site of impaction and duration in situ.13,17,18 Any battery over 1.2 V can cause injury.12 In Australia, this includes all commercially available button batteries as well as so called ‘flat’ or ‘dead’ 3 V batteries. Smaller button batteries are less likely to cause injury11 as they pass through to the stomach but are more often implicated in cases of insertions into orifices (ear, nose, eyelid and vagina) and should not be considered innocuous.19–21

History and examination

While witnessed and suspected ingestions and insertions should always be immediately referred for further management, it is the occult ingestion that may present with less specific symptoms and diagnosis made in retrospect. Therefore, when reviewing presentations of respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, it is critical for GPs to suspect and identify red flags of button battery injury. Symptoms include dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, drooling, fever, cough or irritability.11 Other less common symptoms include dyspnoea, dysphonia, anorexia and chest pain.9 Haematemesis, epistaxis, melaena or altered consciousness should raise the red flag for gastrointestinal bleeding from an aorto-oesophageal fistula.9 Oesophageal button battery injury should therefore be included as a differential prompting a low threshold for imaging for exclusion because of its non-specific nature of presentation.

A concurrent examination should be undertaken to assess haemodynamic stability and safety of the airway. While management of oesophageal button battery injury is time critical, cases of children inserting button batteries into noses, ears, vaginas and nappies have been reported, and thus a focused examination should be considered.11,20–22

Diagnostic imaging

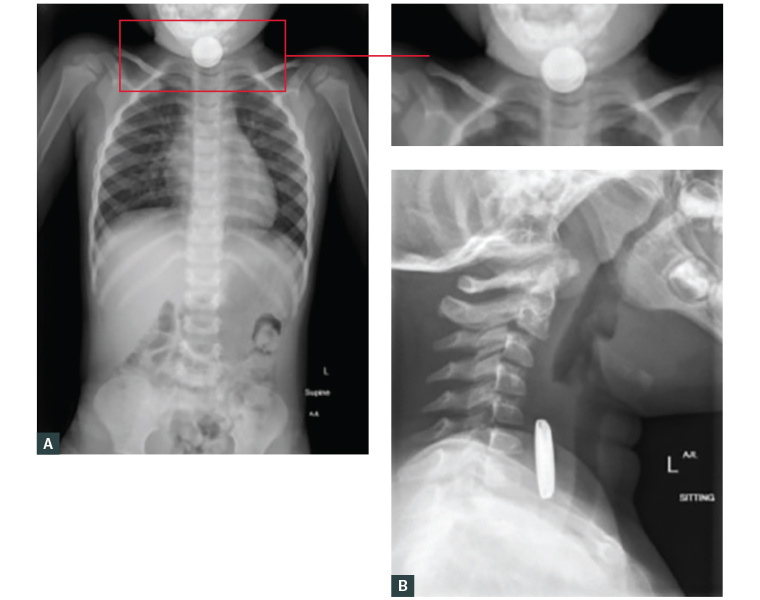

Anterior-posterior and lateral view X-rays from mouth to anus will reveal a circular and radio-opaque foreign body with a ‘halo’/‘double ring’ sign (Figure 3A) or rim/ ‘step-off’ sign (Figure 3B) at the junction of the anode and cathode.23 It is important to note that a button battery under the diaphragm does not exclude transient impaction in the oesophagus.

Figure 3. X-ray imaging antero-posterior and lateral views mouth to anus

A. Antero-posterior view neck to pelvis demonstrating the ‘halo’/’double ring’ appearance of a button battery; B. Lateral view of neck demonstrating the rim/‘step-off’

Management

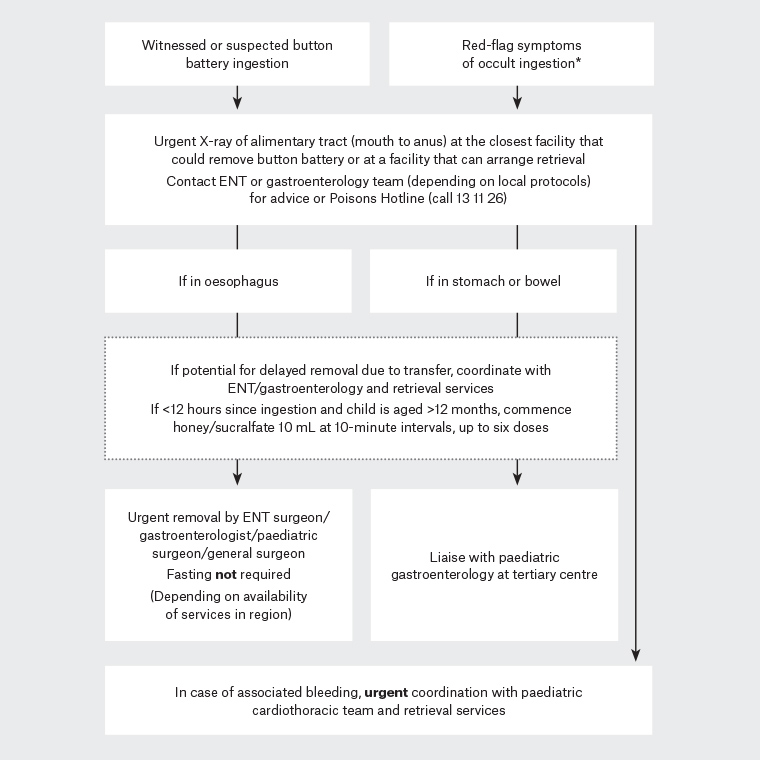

Time to removal of a button battery is the most critical aspect of improving outcomes. A confirmatory X-ray should be obtained at the closest hospital with preference for a site with the facilities to surgically remove the button battery (Figure 4). Multidisciplinary involvement between GP and otolaryngologist, gastroenterologist and emergency physicians is recommended to assist in expediting transfer and management. The Australian Poisons Hotline (available by calling 13 11 26) offers national advice to the public and medical practitioners regarding management to assist with communication to appropriate services.24

Figure 4. Flowchart of management of button battery ingestion

*Symptoms include dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, drooling, fever, cough or irritability. Other less common symptoms include dyspnoea, dysphonia, anorexia and chest pain. Haematemesis, epistaxis, melaena or altered consciousness should raise the red flag for gastrointestinal bleeding from an aorto-oesophageal fistula

ENT, ear, nose and throat

While delays to surgical removal result in worse outcomes, prehospital management guidelines have changed to include administration of two teaspoons (10 mL) of honey or sucralfate at 10-minute intervals (up to six doses) if fewer than 12 hours have passed since ingestion; this may reduce severity of injury.11,25,26 Sucralfate in Australia is currently available as a tablet form only. It can be crushed with 10–20 mL of water for 1–2 minutes to be dispersed and is preferred for children aged <12 months as honey can carry the risk of botulism.27

Delayed presentation with haematemesis, melaena or epistaxis raises suspicion of fistulisation to the aorta that requires urgent paediatric general surgery and cardiothoracic surgery input. Aorto-oesophageal fistulas are usually fatal and reiterate the need to identify BBI early.1 Children with button batteries that have passed into the stomach require consultation with a paediatric gastroenterologist for local protocols. This may include a period of monitoring or surgical retrieval depending on the battery size and age of the child.28–30

Button batteries in ears, noses and other orifices also require timely removal under direct vision. Flushing should not be attempted as moisture results in further chemical current and tissue damage.25 Nasal septal or tympanic membrane perforation, hearing loss, facial nerve damage and permanent tissue damage may occur with delayed removal. Case reports involving eyelids and vaginas carry similar consequences. Skin ulceration has been reported when button batteries have been pushed under plasters,31 as well as reports of a button battery inside a nappy causing scrotal injury.11,22,32

Surgical removal

Oesophagoscopy is the method for removal of larger oesophageal foreign bodies including button batteries. The Australian and New Zealand Society of Paediatric Otolaryngology recommends the use of acetic acid 0.25% intraoperatively to the area of injury to neutralise the pH and reduce the continuation of injury even after removal.13,17,33 Intraoperative assessment of mucosal injury, particularly on the anode surface, will determine post-operative diet, follow-up imaging or follow-up endoscopic assessment.26

Long-term complications

The long-term complications of BBI can be extensive and include oesophageal stricture or perforation, pneumopericardium, mediastinitis, aorto-oesophageal fistula, tracheo-oesophageal fistula, vocal cord paralysis, tracheal stenosis, tracheomalacia, pulmonary infection and spondylodiscitis.11,13 Management of BBI-associated complications may require prolonged hospital admissions and additional procedures, which places increased burden on families and the healthcare system.34 Ongoing collaboration with GPs is required as a result of multidisciplinary involvement as well as associated long-term complications that require follow-up and progress review.

Prevention

It is recommended that GPs take opportunities to advise young families that button batteries should be stored out of reach of children and safely disposed of by returning them to a battery recycling program (Australian Battery Recycling Initiative and Planet Ark). Otherwise they should be wrapped in strong tape and disposed of into a secure waste bin. The new Consumer Goods (Products Containing Button/Coin Batteries) Safety Standards 2020 require all goods containing button batteries (with few exceptions) to have a secure battery compartment and for packaging to include warnings. Button batteries must also be sold in child-safe packaging with warnings.5,35 When purchasing products containing button batteries, the battery compartment should be checked to see if it is secure and requires a device, such as a screwdriver, to open.5 Products that do not meet this requirement should be reported to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) or via the Office of Fair Trading in the relevant state. Educational posters are available for practitioners to place in waiting rooms from Kidsafe (available from https://kidsafe.com.au/button-batteries) and ACCC (available from www.accc.gov.au/publications/button-battery).36,37

Conclusion

BBI is a medical emergency. Approximately one-quarter of BBI events are unwitnessed.10 This, coupled with their non-specific symptomatology and rapid onset of tissue injury, can pose a diagnostic challenge to GPs and emergency departments. As a result of the potentially life-threatening and long-term complications of BBI, a high index of suspicion, timely access to X-ray imaging and reduction of the time to button battery removal is crucial for improving outcomes. There is a role for prehospital use of honey or sucralfate to reduce depth and spread of injury within 12 hours of ingestion.25 GPs have a key role in awareness and community education regarding the dangers of these compact power sources through public health campaigns and management of acute presentations of button battery injury while new legislative changes to products remain to be enforced.