Case

A woman aged 64 years presented with a few weeks of tiredness, night sweats and palpitations. A few weeks prior to presentation, she had experienced an upper respiratory tract infection, which was managed symptomatically.

Approximately five years before her presentation, the patient had been diagnosed with primary hypothyroidism on the basis of clinical features and elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels. She also had elevated antithyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies. She was treated with an appropriate dose of levothyroxine and was adherent to treatment.

On physical examination at her presentation, she had normal vital signs and a normal thyroid gland without palpable nodules. There were no signs of ophthalmopathy. A fine hand tremor was detected. The remainder of the examination was normal.

Initial investigations revealed normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), a TSH of 0.01 mU/L (reference range 0.4–4 mU/L), a free triiodothyronine (FT3) of 6.5 pmol/L (reference range 2.6–6 pmol/L) and a free thyroxine (FT4) of 16.9 pmol/L (reference range 9–19 pmol/L).

Question 1

What are the differential diagnoses?

Question 2

How would you definitively diagnose the patient?

Answer 1

The patient’s clinical features and thyroid function tests (TFTs) are suggestive of hyperthyroidism. The three most likely differential diagnoses for this case are:

- transitioning to Graves’ disease

- thyroiditis

- levothyroxine over-replacement.

However, as this patient had elevated FT3 and normal FT4 levels, levothyroxine over-replacement is the least likely of these three diagnoses. Taking excessive amounts of levothyroxine causes a higher FT4/FT3 ratio than that in spontaneously occurring hyperthyroidism.1

Answer 2

Definitive diagnosis of the patient can be made with measurement of TSH-receptor antibodies (TRAb) and/or determination of radioactive iodine (RAI) uptake.2,3

Tables 1 and 2 detail clinical features and differential diagnoses of hyperthyroidism.

| Table 1. Clinical manifestations of hyperthyroidism3 |

| Symptoms |

Signs |

- Heat intolerance

- Palpitations

- Anxiety

- Tremulousness

- Weight loss despite a normal or increased appetite

- Increased perspiration

- Increased frequency of bowel movements

- Shortness of breath

|

- Lid retraction and lid lag

- Warm and moist skin

- Thin and fine hair

- Tachycardia

- Systolic hypertension

- Tremor

- Proximal muscle weakness

- Hyperreflexia

- Exophthalmos, periorbital and conjunctival oedema, limitation of eye movement and pretibial myxoedema in Graves’ disease

|

| Table 2. Differential diagnoses of hyperthyroidism1,3,11,12 |

| Disorder |

Examination findings |

TFTs |

TRAb |

RAI uptake |

| Graves’ disease |

Large, non-nodular thyroid; ophthalmopathy |

Elevated FT3 and/or FT4, low TSH |

Positive |

Diffuse increased uptake |

| Toxic multinodular goitre |

Multinodular goitre |

Elevated FT3 and/or FT4, low TSH |

Negative |

Multiple areas of focal increased and suppressed uptake |

| Toxic adenoma |

A single palpable nodule |

Elevated FT3 and/or FT4, low TSH |

Negative |

Focal increased uptake |

| Painless (silent) thyroiditis |

Small diffuse goitre or no thyroid enlargement |

Moderately elevated FT4, normal or slightly elevated FT3, low TSH, high anti-TPO levels in 50% of patients |

Negative |

Low |

| Subacute (de Quervain) thyroiditis |

Tender diffuse goitre |

Mildly elevated FT4 and FT3, low TSH, ESR usually >50 mm/hour |

Negative |

Low |

| Ingestion of thyroid hormone |

No goitre |

Elevated or normal FT4 and/or FT3, low TSH* |

Negative |

Low |

*In patients taking levothyroxine, FT4/FT3 ratio is higher than that in spontaneously occurring hyperthyroidism.

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; RAI, radioactive iodine; TFTs, thyroid function tests; TPO, thyroid peroxidase; TRAb, thyroid stimulating hormone-receptor antibody; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone |

Case continued

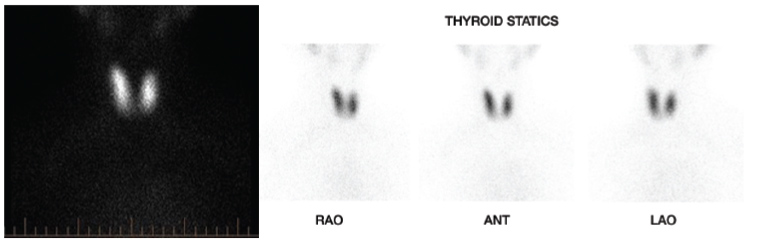

On further investigation, the patient’s TRAb level using a thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) assay was 10.1 IU/L (reference range <2.1 IU/L) and anti-TPO was 152 IU/L (reference range <6 IU/L). A radionuclide thyroid scan revealed a very mildly enlarged thyroid with fairly uniform tracer uptake throughout, consistent with Graves’ disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Radionuclide thyroid scan demonstrating a very mildly enlarged thyroid with fairly uniform tracer uptake throughout, consistent with Graves’ disease

ANT, anterior; LAO, left anterior oblique; RAO, right anterior oblique

Question 3

What is the epidemiology of conversion of hypothyroidism to Graves’ disease?

Question 4

What is the mechanism of this conversion?

Question 5

How long after a diagnosis of hypothyroidism will this conversion occur?

Question 6

What are the management options for Graves’ disease?

Answer 3

The conversion of hypothyroidism to Graves’ disease is uncommon, unlike the reverse, which is well known.4

As a result of long time lapses (eg >20 years) between the two diagnoses in some cases, this phenomenon may not be as rare as previously thought.5

In a large observational retrospective case series by Gonzalez-Aguilera et al in 2018, 1.2% of patients with hypothyroidism developed Graves’ disease.6

This conversion has been seen predominantly in middle-aged women.7

Answer 4

There are two different types of TRAb: thyroid stimulating antibodies (TSAbs) and TSH-blocking antibodies (TBAbs). TSAbs cause Graves’ disease by activating the TSH receptor. TBAbs rarely cause hypothyroidism by blocking the TSH receptor, although the most common cause of hypothyroidism is Hashimoto’s disease due to autoimmune-mediated destruction of the thyroid gland.8,9

While the causes of conversion of hypothyroidism to hyperthyroidism are not well understood, different theories have been suggested. One possible mechanism is a change in the balance between the activities of TBAbs and TSAbs due to an environmental trigger, such as an infection or neck irradiation, in a genetically susceptible individual, which may alter the clinical presentation.5,8,10

Some studies have suggested that switching between blocking and stimulating antibodies occurs in rare cases after using antithyroid drugs for Graves’ disease or levothyroxine for hypothyroidism.8,9

TBAb-induced hypothyroidism and Graves’ disease (TSAb-induced) may be two aspects of one condition.5

Based on the above, the patient might have had TBAb-induced hypothyroidism that then converted to Graves’ disease once TSAb became predominant.9,10 TBAb-induced hypothyroidism is distinct from Hashimoto’s thyroiditis but can still have high anti-TPO and anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) antibodies.8

Answer 5

This conversion can occur at any time.4 It has been reported to develop within a period of 12–24 months on average.8 In one case, hyperthyroidism developed 27 years following a diagnosis of hypothyroidism.5

Answer 6

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment for Graves’ disease should be offered.

Graves’ disease is treated with one of the following three options:

- antithyroid drugs (eg carbimazole)

- RAI therapy

- thyroidectomy.

The selection of therapy requires consideration of patient values and preferences in addition to the clinical features that support a specific treatment option.

Beta-blockers are important in the initial management of Graves’ disease until resolution of hyperthyroidism. These agents improve symptoms such as palpitations, tremulousness, anxiety and heat intolerance.2

Case continued

The test results were communicated with the patient’s endocrinologist. Levothyroxine was ceased, and the patient was commenced on a low dose of carbimazole and a β-blocker. The decision to treat her hyperthyroidism with an antithyroid drug was made on the basis of her mild hyperthyroidism, minimal thyroid enlargement and preference. Her TFTs and TRAb levels were regularly monitored, and adjustments to her carbimazole and β-blocker doses were applied according to her clinical and biochemical pictures.

After four months, the patient’s thyroid function became normal. Her TRAb level returned to the normal range eight months after commencement of treatment. Treatment with antithyroid medications usually continues for a total of 12–18 months.2 In the present case, carbimazole was ceased following TRAb normalisation, taking into account the patient’s preference. Her thyroid function has been monitored since, and there has been no evidence of Graves’ disease recurrence until the time of writing.

Key points

- Patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism can develop Graves’ disease.

- This conversion may not be as rare as previously assumed and may occur at any time following diagnosis of hypothyroidism.

- Suspected cases should be tested for new-onset Graves’ disease and treated appropriately after confirmation of diagnosis.5,8