At the end of 2020, over 82.4 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide, 26.4 million of whom are refugees.1 Under the current Humanitarian program, Australia accepts approximately 13,000 refugees each year,2,3 50% of whom are women or girls.4,5 While many women may choose to migrate voluntarily, millions are forced to leave their countries of origin and resettle in haste, often with little preparation, leaving them vulnerable to violence and exploitation even after resettlement.6–8 Furthermore, the health and sociocultural experiences of refugee women are often overlooked, leaving them exposed to chronic conditions, such as pain, for longer than necessary.9 General practitioners (GPs) are critical to the successful resettlement of refugee women in Australia and play a crucial role in understanding their specific health and social needs.

Worldwide, the burden of chronic pain on disease is escalating and has fast become the leading cause of long-term disability.10 Pain is recognised as chronic when it persists beyond its normal tissue-healing time frame,11 and hence lacks the acute warning function of physiological nociception.12 Usually, pain is regarded as chronic when it lasts or recurs for more than three months.12 However, in refugee women, the immediate effects of physical trauma and pain, including the mechanism of soft tissue injury and subsequent neural adaptation, are likely to result in long-term secondary effects such as chronic pain.13 In order to develop treatment plans and prevention strategies for refugee women, chronic pain needs to be understood in the context of broader social, biological, psychological and physical factors.10

The experience of resettlement for refugee women is a time of change and resilience, and research into vulnerable populations should reflect this unique period of change.14 Longitudinal studies are needed to adequately capture the multidimensional and contextual elements that women of a refugee background experience when resettling into a new country such as Australia. This article uses data from a prospective longitudinal cohort of resettled refugees in Australia from 2013 to 201815 to identify migration factors that play an essential role in the long-term pain outcomes for refugee women. Using the Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) dataset, we will determine the pre- and post-migration factors associated with chronic pain. The BNLA traces the settlement journey of participants from their early months in Australia. The dataset can be used to answer key research questions and provide appropriately informed health services to manage the varying range of challenges that evolve from the resettlement experience. It also provides host nations, such as Australia, with the means to support positive resettlement for women experiencing chronic pain. Ultimately, this may lead to better informed recommendations for service providers when managing chronic pain in women from a refugee background.

This paper outlines the study protocol for a secondary analysis that seeks to identify pre- and post-migration factors associated with chronic pain and long-term disability in refugee women five years after resettlement in Australia.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This protocol outlines a study that will use data from the Australian Government’s BNLA longitudinal survey of resettled refugees living in Australia.15 The BNLA is a national study, conducted by the Australian Government’s Institute of Family Studies, designed to examine how people from a refugee background settle into a new life in Australia.15,16 The authors will not be involved in the study design and data resources as these data have already been collected using the BNLA methods. The BNLA study methods have been published in existing documents,15,16 but are briefly described below. For the current analysis, we will use data collected from the first wave to the fifth wave of the BNLA study. First wave (baseline) data was collected until October 2013, and fifth wave data was collected from October 2017 to March 2018.

Availability of data

The de-identified BNLA data was obtained from the Australian Government’s Department of Social Services. All datasets used in this study are publicly available from the Australian Government’s Department of Social Services (www.dss.gov.au/national-centre-for-longitudinal-data-ncld/access-to-dss-longitudinal-datasets).

Ethics approval

Ethics clearance to access data for the BNLA was granted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies Human Research Ethics Committee (number: LSHM 13/03). All necessary administrative authority to use the BNLA dataset has been obtained by the study authors. De-identified BNLA data is accessible by authorised researchers who have obtained consent from the Australian Department of Social Services. This permission has been obtained by AA and SES. The study team has received ethics exemption from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) to use the data.

Participants

The study will use data derived from participants already collected using the BNLA methods. To be eligible, individuals needed to have been granted a permanent humanitarian visa by the Australian Government in the three to six months preceding the baseline survey.15 Only principal female respondents aged ≥18 years from the initial BNLA study cohort will be included in our analyses. The female respondents are from 15 different countries and at baseline the ages of respondents ranged from 18 to 75 years.15

Sampling

Participants for the BNLA study were drawn from the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection settlement database from 11 locations around Australia. Migrating units were the primary sampling units for the BNLA study,15,16 and consisted of principal applicants and secondary applicants. Principal applicants were the lead participant for our secondary analysis, and were the initial individuals contacted for participation.

Recruitment

The first wave of the BNLA study invited participants to partake in the study through invitations sent in either English or the principal applicant’s native language. Bilingual community engagement officers were also involved in the recruitment process. Bilingual officers helped researchers recruit during the first wave by liaising with community leaders to locate potential participants and provide a bilingual perspective to optimise recruitment of study participants. If the principle applicant agreed to participate, secondary applicants within consenting migrating units were also invited to participate. Invitations to participate in the follow-up waves were extended to participants in the previous wave through mail or telephone.16

Data collection

The study will use data collected via the BNLA survey, which covers a range of key domains relevant to refugee resettlement (eg demographic, housing, pre-migration experiences or health).15 The BNLA survey was administered by a bilingual interviewer or interpreter. To accommodate the diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds of participants, the survey was offered in English and 18 other languages (Amharic, Arabic, Burmese/Mynmar, Chin/Haka, Dari, Hazaragi, Karen, Nepali, Oromo, Pashto, Persian, Somali, Swahili, Tamil, Tigrinya and three other confidentialised languages).15,16 The first, third and fifth waves of the BNLA surveys were conducted through face-to-face visits. Waves two and four used computer-assisted telephone interviews.15

Variable selection

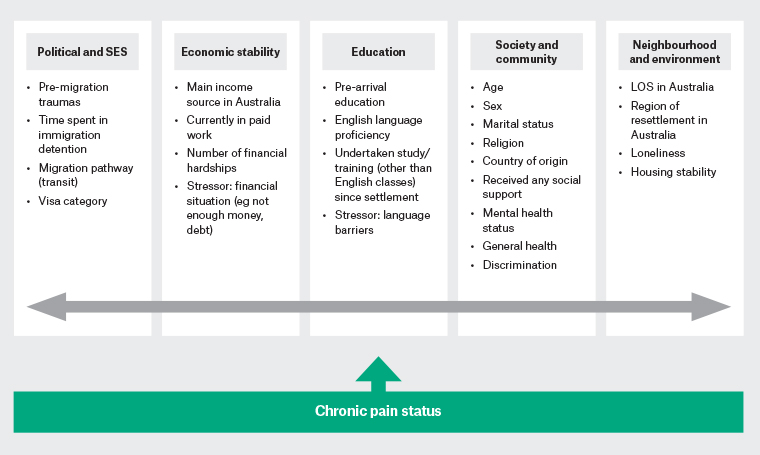

Variable selection for this study is informed by a conceptual framework guided by Cross-Denny and Robinson’s social determinants of health.17,18 This framework can assist in developing effective interventions to ensure all variables associated in the development and management of chronic pain are identified, evaluated and addressed. Furthermore, a review of the literature has helped inform the selection of 25 candidate variables from the BNLA dataset to include in our analysis. Our adapted model involves five key determinants with their relevant variables (Figure 1),18 and have been further categorised into pre- and post-migration predictor variables (Table 1) that have been extracted from the BNLA survey data for analysis. Links to the BNLA survey questionnaire and user guide are available online (https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataverse/bnla;jsessionid=8c6f84f76 7ab582b990802dee45c?q=&types=files &sort=dateSort&order=desc&page=1).

Figure 1. Chronic pain framework developed for analysis – conceptual framework for the social determinants of health in resettled refugee populations. Click here to enlarge

LOS, length of stay; SES, socioeconomic status

| Table 1. Pre-and post-migration predictor variables |

| Pre-migration |

Post-migration |

- Pre-migration trauma

- Time spent in detention

- Migration pathway

- Pre-arrival education

- Age

- Sex

- Marital status

- Religion

- Country of origin

- Visa category

|

- Main income source in Australia

- Currently in paid work

- Number of financial hardships

- Financial stressors

- English language proficiency

- Undertaken study/training since settlement

- Language barrier

- Social support

- Mental health status

- General health

- Length of stay in Australia

- Region of resettlement in Australia

- Loneliness

- Housing stability

- Discrimination

|

Outcome variables

Chronic pain

The primary outcome for this study will be chronic pain status. To assess chronic pain in the current study, the question ‘How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks?’ will be examined longitudinally between waves one, three and five. Participants responded to this question using a six-point rating scale ranging from none (1) to very mild (2), mild (3), moderate (4), severe (5) and very severe pain (6). For this study, we will consider participants who responded with no pain, very mild pain or mild pain as not having pain, with those who responded with moderate, severe of very severe pain as having pain.19 Only participants who report having severe pain across two consecutive waves (ie wave one and three, or wave three and five) will be considered to have chronic pain.

Long-term disability

To determine whether women had a long-term disability in the study, the question ‘Do you have a disability, injury or health condition that has lasted or is likely to last 12 months or more? ’will be analysed longitudinally between waves one, three and five. Participants are given a single response of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to this question. Participants who respond ‘yes’ to this question at wave one, three or five will be considered to have a long-term disability.

Data analysis

Data will be analysed using Stata/IC 15.1 software.20 Descriptive statistics will be used to describe the overall characteristics of the sample population, such as sociodemographics, migration experience, and health outcomes. Logistic regression models will be used to examine the association between the various migratory factors and chronic pain. Robust variance estimators will be used to account for potential clustering.21

A two-step modelling process will be used to determine the pre-and post-migration factors associated with chronic pain. First, univariate regressions will be used to examine associations between predictor variables and chronic pain with variables retained at P <0.1.22 Collinearity will be explored using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and when collinearity is identified (VIF >2.5), the variable with the higher R2 on univariate analysis will be retained for entry into the multivariate model. Second, multivariate logistic regression analysis will examine associations between candidate variables and chronic pain. A final model will be computed using all significant pre- and post-migration factors. Interactions between candidate variables will also be considered to identify any interaction effects. Last, we will determine the proportion of women who report both chronic pain and long-term disability. This will be used to inform our subgroup study, which will involve a logistic regression analysis to determine the pre- and post-migration factors associated with chronic pain in women who also report having a long-term disability.

Discussion

Our secondary analysis of the BNLA dataset seeks to examine the association between pre- and post-migration experiences and chronic pain in resettled humanitarian refugee women residing in Australia. This inquiry will aim to identify meaningful determinants among refugee women during the initial and later stages of their resettlement and whether these migrations factors impact on chronic pain.

With migration increasingly viewed through the image of terrorism, potential difficulties are likely to arise from personal, religious and cultural affiliations that can influence refugee women’s resettlement experiences and wellbeing. Migration-related factors experienced prior to or while seeking refuge, such as trauma exposure, migrating alone or detainment, can have long-term clinical implications for both physical and mental health.23 Additionally, factors after arrival into Australia, such as ability to access comprehensive healthcare, can determine the trajectory of wellbeing and cause many initial symptoms to persist longer than necessary. Evidence as to whether pre- and post-migration factors such as trauma, economic stress, sense of purpose or community support impact the experience of chronic pain is lacking in the literature.

Exploring the above factors over time will provide new and rich insights into the health of resettling refugee women and guide the understanding of adversities refugee women face, as well as how health outcomes change from the point of arrival to years of residency in Australia. This knowledge has the potential to build an evidence base for frameworks aimed at improving refugee resettlement programs and shape better practice protocols for chronic pain management in general practice.