Case summary

A woman aged 64 years presented with a three-year history of vulvar itch and skin fragility with associated superficial dyspareunia. She had a long-term monogamous partner, and cervical screening was up to date and normal. She also had a history of diet-controlled type 2 diabetes.

Self-management with multiple over-the-counter (OTC) topical and oral treatments for presumed thrush were ineffective. Previous low vaginal swabs had been negative for candida.

Her examination findings revealed white plaques to the vulva, resorption of the labia minora, a fissure and burying of the clitoral hood.

Question 1

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Question 2

What are other differentials to be considered?

Question 3

What causes this condition?

Question 4

What investigations should be done?

Question 5

How should this condition managed?

Question 6

What are the possible long-term complications of this condition?

Answer 1

This patient presented with typical features suggestive of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Vulvar lichen sclerosus affects women of all ages, including children, but is most common in postmenopausal women.1 The true prevalence is unknown but estimated at approximately one in 70 women.2 Cardinal symptoms are pruritis and skin fragility, but patients may also present with pain, dyspareunia, discharge and irritation.2,3

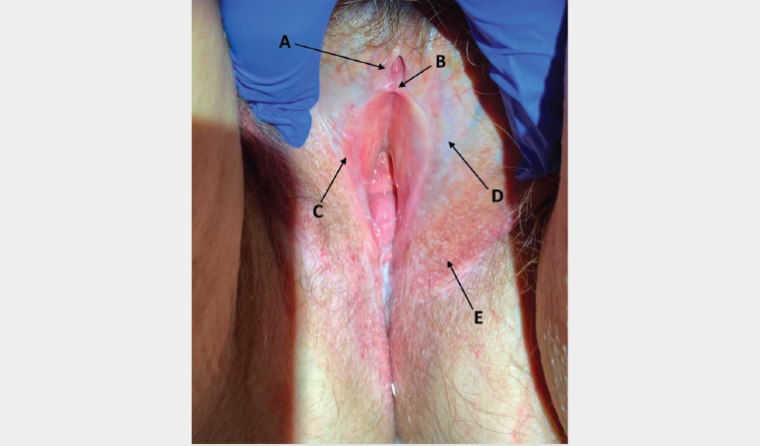

Typical clinical features of vulvar lichen sclerosus (Figure 1) include white plaques, hyperkeratosis, purpura, loss (resorption) of labia and clitoral hood, burying of the clitoris, adhesion of labia, midline fusion and introital narrowing.3 The white plaques may be confluent and extend around the vulva and perianal skin in a figure of eight pattern.

Figure 1. Vulvar lichen sclerosus

A. Burying of clitoral hood; B. Subtle fissure; C. Resorption of labia minora; D. Pallor typical of active lichen sclerosus; E. Prominent capillaries from topical corticosteroid use. The vulvar architectural changes of A and C can be seen in well-controlled disease as an indicator of chronicity, whereas points B and D are markers for active disease. Point E is secondary to use of topical steroid on labia majora (incorrect location of self-application).

Women with lichen sclerosus typically experience a delay in diagnosis, averaging 5–15 years from the time of onset of symptoms.1 Barriers to diagnosis include patient embarrassment in reporting their symptoms and preference to self-manage with OTC remedies, attribution to other aetiologies (eg vulvovaginal candidiasis) and failure to undertake vulval examination with symptoms of itch. The general practitioner has a crucial role in ensuring early diagnosis and initiation of therapy, especially given opportunities for examination and diagnosis during routine care provision (eg cervical screening).

Answer 2

Features in this case that strongly suggest lichen sclerosus are the history of itch and skin fragility in combination with the clinical findings of architectural changes to the vulva and associated pallor.

Other differentials to consider that can present with vulvar itch or pain include lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, dermatitis, chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis and vulvar neoplasias (namely squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] and vulval intraepithelial neoplasias). It is recommended that a biopsy is taken where there is diagnostic uncertainty.

Answer 3

The exact pathophysiology of lichen sclerosus remains unclear. There is some evidence to support an autoimmune aetiology,4 and it is associated with another autoimmune disease in up to 28% of patients.5 There is a particular association with autoimmune thyroiditis, alopecia areata, vitiligo and pernicious anaemia.6

Answer 4

Vulvar lichen sclerosus can be diagnosed clinically; however, if there is diagnostic uncertainty, a biopsy should be considered. A biopsy should be taken by a clinician with appropriate training and skill and pathology interpreted by a dermatopathologist. Further investigations include a low vaginal swab to rule out candidiasis and thyroid function tests.

Answer 5

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic condition with no cure, yet appropriate treatment can effectively manage symptoms and prevent the complications of scarring and SCC development.3 First-line treatment is the application of potent to very potent topical corticosteroids (TCSs) such as clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment (which is a compounded formulation) or betamethasone dipropionate (0.05%) in optimised vehicle.7 A typical regimen would be daily application of a TCS for a month, then alternating days for a month, then using it 2–3 times per week on an ongoing basis.7 Ongoing proactive treatment, even if symptom free, is recommended to reduce the risk of SCC development and scarring.8

Typically, following the diagnosis and introduction of a TCS, a patient is reviewed at three and six months. This review (or ‘early review’) is important to ensure resolution of symptoms, improved appearance, patient compliance and patient understanding.

Women with lichen sclerosus should also be advised to avoid possible vulvar irritants. These may include soaps, fragranced oils, tight-fitting underwear and douching. Many women may also benefit from the addition of a topical bland emollient to prevent friction on fragile mucosa.

Surgery is occasionally required for women who have severe fusion with associated functional problems, such as difficulty with micturition. Women who undergo surgery need close post-operative follow-up with potent TCSs to prevent recurrence.

Answer 6

The scarring from lichen sclerosus can result in significant architectural changes and scarring to the vulva. This may have a significant impact on quality of life, affecting physical activities and impairing psychosexual, psychological and social wellbeing.9

For patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus, there is an approximately 4–6.7% increased risk of developing SCC.3 The use of very potent TCSs long term has been associated with SCC prevention.10 Yet while the symptoms and further disease progression can be well controlled by TCSs, these will not reverse existing vulvar scarring and architectural changes.3 As such, early initiation of treatment is essential for minimising long-term complications.

Case continued

The patient was diagnosed with vulvar lichen sclerosus and initiated on appropriate therapy. At her 12-month review, she was found to still have active disease. At this time, she was applying clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to the vulva approximately 1–2 times weekly but to the wrong location. As shown in Figure 1, point E, the patient had been applying the ointment to the labia majora, resulting in prominent capillaries from TCS use. Education was provided regarding where to apply the medication to optimise management. She was also instructed to increase the frequency of TCS application. Ongoing review was arranged for six months’ time.

Key points

- Vulvar lichen sclerosus should be considered in women presenting with chronic vulvar itch.

- Treatment is typically with potent to ultra-potent topical corticosteroids.

- Treatment should be continued long term to reduce the risk of SCC development and scarring.