Case

A child aged 14 years presents to their general practitioner (GP) with their father on a Saturday morning. The child was recently diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) by a local paediatrician and is being treated with methylphenidate. The child has regularly attended the practice with their mother. The GP has not previously met the father. The GP is aware that the child’s parents separated acrimoniously 12 months ago, but is not aware of any allegations of family violence.

Today, the father tells the GP that he has not seen his child for the past six months because he has been imprisoned, but the child is staying with him this weekend as part of an informal parenting agreement with the child’s mother. The father is concerned that his child is on high doses of ‘speed’ for a ‘nonsense diagnosis’. He tells the GP that he stopped the methylphenidate last night, does not consent to the child continuing the methylphenidate and requests a copy of the child’s medical record so he can obtain a second opinion.

The GP has been monitoring the dose of methylphenidate (and the child’s clinical response to it) in collaboration with the paediatrician and the child’s mother. The mother has previously commented that the child’s behaviours and school reports have improved significantly since commencing methylphenidate, and she was keen for it to be continued. Having confirmed the father’s identity and his relationship to the child (as this information was documented in the child’s medical record), the GP takes a brief history from the child at today’s consultation. The child reports fewer ‘meltdowns’ since commencing the medication and denies any side effects. On examination, the child’s blood pressure is within normal limits. The GP explains to the father that they consider the methylphenidate to be effective and recommends that it be continued, but the father remains concerned.

What should the GP do?

Question 1

Should the child’s views be considered?

Question 2

Is the consent of both parents required for medical treatment of the child?

Question 3

Can one parent prevent the release of their child’s medical records to the other parent?

Answer 1

Regardless of the parents’ wishes regarding their child’s medical treatment or access to their child’s medical records, the GP should first consider the views of the child and assess whether the child has capacity to consent to or refuse treatment and/or parental access to their records.1 In most Australian jurisdictions, the common law only allows individuals aged under 18 years to consent to medical treatment (and related matters, such as the release of records) if they have ‘sufficient understanding and intelligence’ to enable them to ‘fully understand’ what is proposed (Secretary, Department of Health and Community Services v JWB and SMB (1992) 175 CLR 218). This is referred to as ‘Gillick competence’. In New South Wales (NSW), a medical practitioner who provides treatment with the consent of a child aged 14 years or over will have a defence to any action for assault or battery (Minors (Property and Contracts) Act 1970 (NSW), s 49). In South Australia (SA), children aged 16 years or over can consent to medical treatment, whereas children aged under 16 years may only consent to treatment if two medical practitioners agree that ‘the child is capable of understanding the nature, consequences and risks of the treatment and that the treatment is in the best interests of the child’s health and well-being’ (Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA), s12). The level of maturity required to provide consent will vary with the nature, complexity and risks of the proposed medical treatment. Box 1 sets out some of the factors considered by courts when determining Gillick competence. This might be instructive to GPs also considering whether a child is Gillick competent.

| Box 1. Factors considered by courts when determining Gillick competence4 |

Courts will consider medical opinion about the child’s capacity, and the child’s:

- age

- psychiatric, psychological and emotional state

- understanding of the nature and consequences of the illness and its treatment

- maturity, intellect and life experience

- ability to understand wider consequences of the decision, including the effect on other people, and moral and family issues.

|

Although not applicable to this case, there are also ‘special medical procedures’ to which Gillick-competent children cannot consent and which fall outside the zone of parental responsibility because they are invasive, irreversible or might have serious consequences for the child. These procedures require court approval and include sterilisation, pregnancy termination, experimental drug treatment and bone marrow harvesting.2 In relation to treatments for gender dysphoria, court approval is only required if there is a dispute about capacity, the diagnosis or treatment (Re Imogen (No 6) [2020] FamCA 761). As with adults, reasonable life-saving treatment might be administered in an emergency without the consent of either parent or a Gillick-competent child (see, for example, Children and Young Person’s (Care and Protection) Act (NSW), s 174). Notwithstanding the capacity of some children to consent to medical treatment, courts have inherent jurisdiction to overrule a child’s decision if the court considers that it is not in their best interests (X v The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network [2013] 85 NSWLR 294).

Where a child’s Gillick competence is being relied upon to determine the outcome of a parental dispute about treatment, it would be prudent practice to obtain a second opinion about the capacity of the child to consent to the treatment proposed. Within larger health services, institutional policies or procedures might also provide guidance to GPs around consent in the context of care for children, and these should be observed.

Answer 2

Where a child is deemed not to be Gillick competent, Australian Law (Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), s 61C) presumes that both parents are entitled to full and equal parental responsibility for their child aged under 18 years. This applies whether the parents are married, cohabiting, separated or divorced. The parent with whom a child primarily resides has no greater decision-making power than the other parent,3 and extended absence from a child’s life (such as due to imprisonment) does not itself prevent a parent from exercising parental responsibility. The presumption of equal shared parental responsibility does not apply if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that a parent has engaged in family violence or abuse of that child (Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), s 61C(2)). The presumption will also be displaced if a court makes parenting orders removing parental responsibility from one parent (Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), s 61C(3)).

It is advisable to ask both parents if parenting orders exist that remove either parent’s rights or responsibilities with respect to medical decision making for the child. Generally, at least one parent will disclose to the GP or practice the existence of orders in order to protect the child’s interests. If neither parent discloses to the GP the existence of such orders, then it may be reasonable for the GP to assume that no orders exist because it would be difficult for a GP to otherwise verify their existence. However, if at least one parent discloses the existence of such orders, then a copy of these orders should be requested, as outlined below.

If no such orders exist in relation to a child that is not Gillick competent, then both parents are likely to have shared parental responsibility and should attempt to resolve their disagreement themselves. In this case, the father has been imprisoned for the past six months, and might not have been involved in prior conversations with the GP or paediatrician about the diagnosis or treatment. Therefore, one important step in trying to resolve this situation might be to provide the father with resources and offer him a follow-up appointment to further discuss his concerns. Indeed, his request for a second opinion might not be unreasonable if it assists him to better understand the diagnosis and treatment, including the benefits and risks.

Where there are no parenting orders, it is not unlawful to act on the wishes of one parent, even when it is known that the other parent opposes those wishes. Thus, it would not be unlawful to restart the child’s methylphenidate in this case. Similarly, it would not be unlawful to refer the child for a second opinion, as requested by the father. However, acting on the wishes of one parent when it is known that the other opposes those wishes could expose the GP to the risk of a complaint. Therefore, unless there are potentially serious risks to the child, it would be prudent not to take sides and, instead, to wait until the disagreement is resolved before proceeding. Even if the GP strongly agrees with the mother that continuing treatment is in the child’s best interests, restarting treatment could result in a potentially harmful scenario where the child oscillates on and off treatment during periods of custody with each parent. Conversely, facilitating a referral for a second opinion, even if opposed by the mother, might assist in resolving the dispute expeditiously and might be in the child’s overall long-term interests if the second practitioner to whom the child is referred is supportive of ongoing treatment. It would be critical for the GP to obtain independent advice in these challenging circumstances about how best to proceed.

If the parents are unable to reach an agreement, then courts might intervene and order a particular course of action (Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), s 65 or s 67ZC). If this occurs, or if parenting orders exist, the GP should request and file a copy in the child’s medical record, and seek advice from their medical defence organisation about how best to give effect to them. Understanding and correctly interpreting court orders or parenting orders requires specialist medicolegal knowledge and can have implications for the treatment of the child.

Answer 3

As with consent to medical treatment, each parent has a right to access their child’s medical record, unless the child is deemed capable of refusing this or where a court has made parenting orders preventing this. Health records legislation in several Australian jurisdictions recognises that children aged under 18 years might have capacity to make decisions about the collection, use or disclosure of their health information (see, for example, Health Records Act 2001 (Vic), ss 3 and 85(2)(a)(i)). However, requirements vary between jurisdictions. In the ACT, a GP may require the consent of a child aged between 12 and 18 years before releasing the child’s medical records to a parent (Health Records (Privacy and Access) Act 1997 (ACT), s 13BA(5)). In the case of the MyHealth Record, parents may not access a child’s record after the child turns age 14 years, unless the child grants them permission (My Health Records Act 2012 (Cth), s 6(5)).

Although there is no legal requirement to inform one parent that the other has requested the child’s records, it is often good practice to do so, because this might alert the GP to important information within the medical record that should not be released to the other parent. For example, the record might include allegations of abuse made by a child or parent against the other parent, which, if disclosed, could create a risk of further harm to that child or parent. Similarly, sensitive personal information about one parent (eg current address or contact details) should not be disclosed to the other parent. If information is identified that should not be disclosed, that does not generally mean the entire record should be withheld. Instead, only the relevant information or entries should be withheld or redacted. The GP should contact their medical defence organisation for advice on what information to disclose or withhold if they are uncertain, as well as information on how to redact information and how to manage the costs associated with complying with a request for medical records.

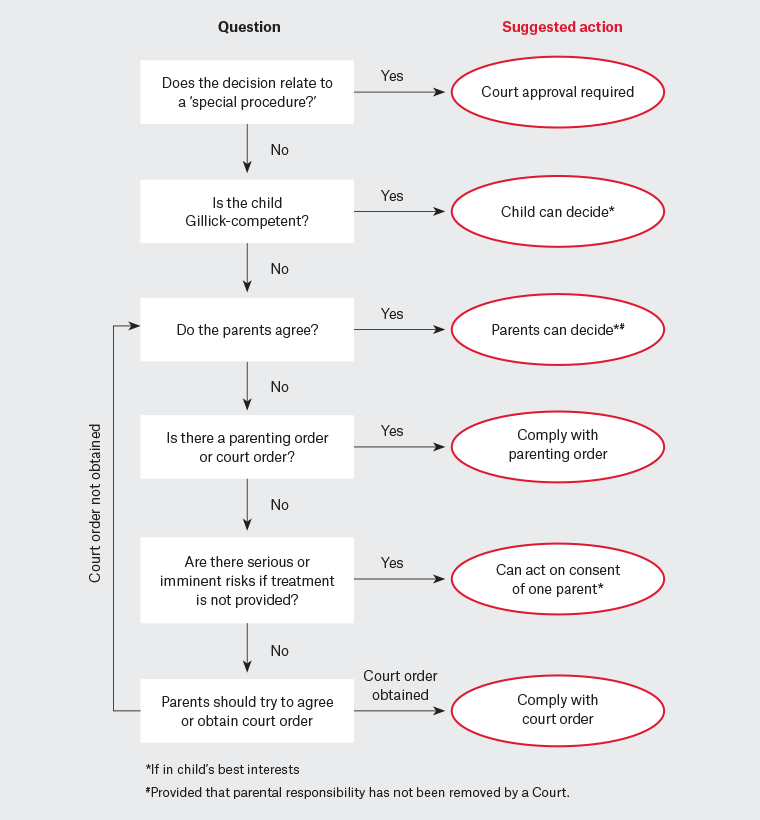

Figure 1 provides a decision tree to assist in navigating parental disagreement regarding treatment or access to their child’s medical records. The information in this article, including Figure 1, is intended to be general information only and is not a substitute for legal advice. Readers should contact their medical defence organisation for advice in relation to the specific circumstances of any clinical situation that might arise in their practice relating to children and consent.

Figure 1. Possible approach for navigating parental disagreement about treatment.

Key points

- Where parents disagree about treatment or access to their child’s medical records, the first step is to consider the best interests of the child and whether the child can consent to treatment or the release of medical records.

- Where a child is not Gillick competent, the presumption at law is that both parents have equal rights to authorise medical treatment or to request access to their child’s medical records, unless there is a court or parenting order to the contrary, or if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that a parent has engaged in family violence or abuse of that child.

- Where separated parents disagree about treatment or access to medical records, they should be encouraged to resolve any disagreement independently.

- GPs can provide factual information about the risks and benefits of treatment in order to assist this process, but are advised to avoid taking sides.

- GPs should seek advice from their medical defence organisation if they are presented with a copy of a court order or parenting order, or if there are concerns that releasing a child’s record to a parent might give rise to serious harm to the child or another person.