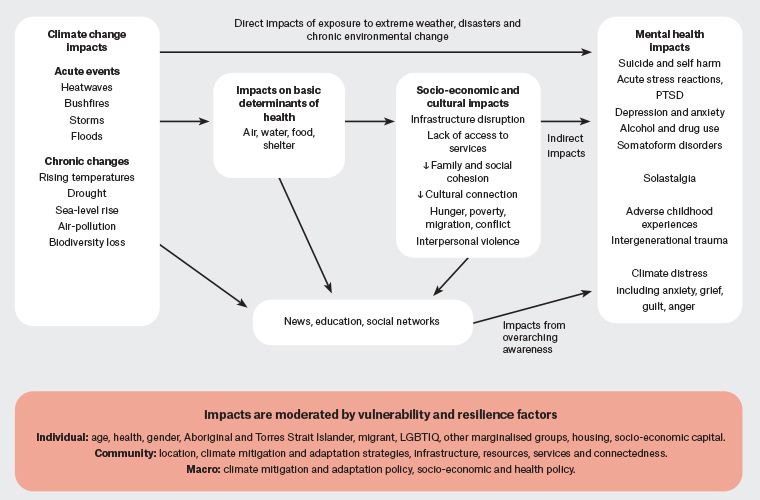

Climate distress can be described as psychological distress in response to the overarching awareness of climate change. It forms part of the broader spectrum of climate change impacts on mental health, which are summarised in Figure 1.1–5

Figure 1. Climate change and mental health: exposure, impacts and mental health sequelae. Click here to enlarge

LGBTIQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender intersex queer; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

SMART, Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time bound.

Concern about climate change is rational given the evidence.6–8 Reported emotions include anxiety, guilt, hopelessness, depression, anger, grief, shame or powerlessness.9–11 Climate-specific psychological responses include climate anxiety (worry, dread and fear evoked by awareness of climate change and its impacts) or eco-anxiety,9–11 solastalgia (feelings of distress, loss and grief arising from environmental change affecting a person’s sense of connection to place)12 and ecological grief.13

Some distinctive aspects of climate anxiety have been identified as the globally shared significance of climate change, the ongoing and progressive nature of the threat and the degree of uncertainty about specific impacts at given times and locations. Climate change has been described as both an existential threat and a threat to ontological security, challenging not only our literal existence, but also our core beliefs and understanding of reality.14 For some, especially younger generations, the threat of climate change may assume an interpersonal dynamic, where the actions of others are seen to threaten fundamental safety and values, resulting in a sense of betrayal or moral injury.11

The experiences of climate distress for people in marginalised positions will differ from those with social, political, economic and geographic privilege.3–5 For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, there may be additional dimensions of loss of cultural identity through destruction of sacred landscapes alongside the burden of intergenerational trauma.5,15,16

In much of day-to-day life, climate change is largely invisible and thus able to be ignored. However, when encountered, the inherent cognitive dissonance can create psychological discomfort (eg many people are aware of the harmful consequences of fossil fuel use yet remain reliant on petrol-fuelled transportation and lack access to other options, especially in rural areas).

Societal understanding of climate science is variable and polarised.17 In some instances climate change is actively denied, with those expressing concern experiencing derision. Feelings about climate change can be experienced as disenfranchised emotions, lacking accepted means of expression, and therefore may be self-censored. A potent example is climate grief, which lacks social norms and ritual associated with other types of loss that may enable coping.13

Climate change also cannot be described entirely as a problem either within or without individual control, thus creating a complex dialectic between personal versus collective responsibility and agency. The extent to which individuals have control over their individual environmental impact is largely determined by their sociopolitical context. Children, for example, often have little agency over what goods are purchased in a household.

However, emotional engagement with climate change can also be a positive experience. The experience of a climate-related event creates greater knowledge and understanding of climate change.18 It can promote self-efficacy and positive psychological adaptation while strengthening resolve and responsibility for climate action.9

Epidemiology of climate distress

Global studies have found that 84% of young people are at least moderately worried about climate change, with almost half reporting that these feelings negatively affect daily life and functioning.11 Climate anxiety and distress in that sample correlated with perceived inadequate government response and a sense of betrayal.11

A study of 5500 Australian adults found that 25% met screening criteria for clinical anxiety or trauma symptoms related to climate change, with younger people most affected. Among those aged 18–34 years, 20% reported functional impairment affecting their work, family and social life due to climate anxiety.19 Climate distress was experienced by all ages, in both rural and urban locations and across the socioeconomic spectrum.20

Clinical approach to climate distress

Given the prevalence and wide spectrum of responses, individuals need to be supported without pathologising distress or framing it as an individual struggle, while remaining alert to comorbid mental illnesses.3,5,21

A trauma-informed and person-centred approach is required. Distress about climate change must be understood in the context of the person’s unique circumstances, experiences and identities. As with all psychological care, the clinician needs insight into their own knowledge, values and biases when assisting patients with climate distress.21–23

The climate crisis, in common with many other determinants of health, brings the broader natural and sociopolitical environment into the consulting room. Although shared concern can be a leveller between the clinician and patient, ultimately it is the patient’s own story and agenda that takes precedence, while acknowledging that climate change is not a problem the patient must face in isolation.

The skill set of general practitioners (GPs) has much to offer in response to climate distress.24 GPs are well versed in supporting people through life’s common stressors, empowering patients to adapt and grow from adversity through long-term therapeutic relationships.25 GPs can sit with uncertainty and understand complex adaptive systems, both of which are important for the ‘wicked problem’ of climate change.24

Assessment

As a starting point, displaying tailored visual material may allow patients to more comfortably express concerns they may otherwise not disclose. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) has developed such resources for climate change.26 Consider routinely asking questions to explore existential concerns in mental health consultations. For example, ‘How does the future look to you? Do you worry about the future for yourself, your family or the world in general?’ This may then invite further discussion because climate change has been identified as one of if not the most common responses to open-ended questions about serious problems facing the world.18,27 Climate anxiety screening tools have been developed in research, but their clinical utility requires further evaluation.28

If climate concerns are expressed, explore them empathically and non- judgementally. Enquire about the person’s understanding of climate change and their exposures to climate-related events, personally, within their family and community, or through the media. Assessment of climate distress requires understanding the range of adaptive responses to the current climate trajectory. The young person who factors climate change into their decision not to have children may be basing this on a rational appraisal of the situation,9,11 whereas certainty that the world is ending next week is inconsistent with adaptive climate distress and may represent a delusional belief.

During assessment, determine the severity and duration of the symptoms, functional impact and the presence of helpful or unhelpful coping strategies (eg using substances to manage distress that may worsen mood). Assess suicide risk, especially when feelings of despair and hopelessness are expressed. Consider concurrent life stressors, and ask about the response of family and friends to the person’s concerns, and their ability to provide support. For patients actively involved with environmental action, ask about signs of burnout, such as reduced efficacy, cynicism and exhaustion.

Climate distress may co-occur with generalised anxiety, depression, other mental illness, a history of trauma or grief, and the bidirectional relationship of these factors should be explored sensitively.

Management

Listening and validation during the assessment process may be sufficient treatment in itself for some individuals. Creating a safe, receptive space to discuss feelings may provide relief and hope. Opening a discussion may provide opportunities for evidence-based psychological strategies to be used.

Adaptive coping with climate distress can be considered across three domains, namely emotion-, problem- and meaning-focused coping, with suggestions for specific psychological strategies for each described in Table 1. Evidence particularly supports meaning-focused coping as being associated with reduced distress and greater behavioural engagement, but all domains can be usefully explored.14,29

| Table 1. Domains of coping and key skills for managing climate distress |

| Coping domains |

Psychological strategies |

| Emotion-focused coping: addressing the thoughts and feelings associated with climate change |

Relaxation skills

Mindfulness

Self-compassion and self-care

Social media/news breaks

Interpersonal skills to manage conflict and boundaries

Nature connection

Identify and strengthen support networks |

| Problem-focused coping: environmentally oriented behavioural responses to climate change |

Education about climate change impacts, mitigation and adaptation

Problem solving and SMART goal setting to identify and implement personally meaningful action

Mental health interventions with climate co-benefits (eg increased physical activity from active transport)

Individual and collective pro-environmental action |

| Meaning-focused coping: strategies drawing on values, trust and hope |

Exploring values that may always be held regardless of outcome, as opposed to goals that may or may not be reached

Reframing emotional pain as an expression of one’s values (eg reframing grief as a component of love, or anger as a sense of justice or guardianship)

Enhancing psychological flexibility (eg the ability to hold conflicting truths simultaneously)

Developing an expanded sense of self, including the social and ecological self

Enhancing connection to others and nature while viewing care for oneself as part of care for the planet

Gratitude practices

Cognitive reframing (eg ‘What’s the point, my actions won’t change anything and no-one cares’ vs ‘Lots of people around the world care deeply and are making changes. I don’t know what the future may hold’)

Cultivating authentic sources of hope despite a difficult reality |

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can build coping skills and help reframe unhelpful thoughts, although care must be taken to avoid invalidating when challenging thoughts and feelings about climate change. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is of interest as an approach in that it does not dispute the accuracy or otherwise of thoughts or emotions; rather, it examines their ‘workability’ in allowing mindful connection to the present and taking values-guided action, with psychological flexibility as the goal.30,31

Taking action

Emerging evidence suggests that acting on climate change mitigates climate distress through reduced personal stress and improved optimism.32 Clinicians can support individuals to identify action which is meaningful and sustainable for them (eg eating less meat or joining a local environmental group).9,14 Encouraging collective pro-environmental action can be empowering: enabling and sustaining hope while providing social support from like-minded peers.9,33 The case study in Box 1 describes a presentation in which this approach may be useful.

| Box 1. Case study |

|

Nineteen-year-old Tom feels angry about plans for new fossil fuel projects in the region. His parents’ home has been flooded three times in the past 18 months and they are no longer able to afford insurance. He is currently couch surfing. Tom feels government inaction on climate change is responsible for more frequent flooding, and he expresses feeling a sense of hopelessness about the future. He has no suicidal ideation. He has worked part-time in retail since finishing year 12 and says he doesn’t see the point in further study because ‘the world is totally messed up anyway’.

You listen and validate Tom’s concerns, help him identify his values of justice and integrity that underpin his frustration and teach him some simple grounding strategies for when he feels overwhelmed. You discuss some local youth groups working to oppose the fossil fuel projects that he could connect with. Tom is enthusiastic about meeting others who share his concern and being able to channel his feelings into values-guided action.

|

Nature connection

Time in nature is a consistent theme in the management of climate distress. It is telling that Indigenous knowledge and culture embeds what research is showing: that nature connectedness is important for human wellbeing.15,34,35 Nature activities promote physical activity, mindfulness, social inclusion, emotional wellbeing, connection to place, and pro-environmental attitudes.36 Nature-based activities can have benefits to both the environment and health; these are termed climate ‘co-benefits’ and include active transport (eg walking) and community gardens.15,36

Group approaches

Normalising climate distress within a collective process can be validating,21,22 whereas isolation can worsen climate distress.9,11 Several models exploring climate distress in group settings, with clinician or peer support, are listed in Table 2.37,38

| Table 2. Professional development and patient resources |

| Further professional development opportunities |

Psychology For A Safe Climate offers a pathway for further professional development as a climate aware practitioner through a series of webinars and workshops38

The RACGP Climate and Environmental Medicine specific interest group offers opportunities for peer connection |

| Resources for patients |

Written material

Professionally led support groups

- Psychology for a Safe Climate38

|

Tailor the approach to the individual

For individuals with mild to moderate distress, listening, validating and providing psychological interventions as described above may be sufficient to bring about relief and enable ongoing self-management. For individuals with more severe distress, functional impairment or at risk of harm, and for those with co-occurring significant mental illness, consider more intensive interventions, including medication and the involvement of other services and providers, as appropriate. For those with severe distress, the initial focus should be on self-care, engagement with pleasurable activities and limiting media exposure, with values-guided action being a later step. For highly active individuals experiencing burnout, it is important to give support to stepping back, at times, from some or all pro-environmental activity.

Conclusion

Feeling distress is a rational response to climate change, presenting with anxiety, among other manifestations. Distress relating to climate change has some distinct dimensions that merit understanding. Clinicians will naturally vary in their awareness and level of concern about climate change, but the GP skill set is well suited to managing these presentations.

Validation of rational distress is key, while at the same time assessing and treating any significant mental illness. A supportive approach drawing on evidence-based strategies that support adaptive coping, hope and meaning is recommended.

Other helpful approaches may include encouraging individual and collective action, time in nature and group-based therapy and peer support; however, more research is needed to determine the most effective interventions.

Key points

- Climate change is a significant existential threat that most Australians are rationally worried about.

- Some people experience significant distress and functional impairment that may reach a diagnostic threshold.

- Adaptive coping strategies from the domains of emotion-, problem- and meaning-focused coping should be supported and individualised to the needs of the patient.

- Promising approaches include supporting collective action, nature connection, group-based therapy and peer support.