Wherefore to some, when being abed they betake themselves to sleep, presently in the arms and legs, leapings and contractions of the tendons, and so great a restlessness and tossing of their members ensue, that the diseased are no more able to sleep, than if they were in a place of the greatest torture.

– Thomas Willis

The statement above by English Physician, Thomas Willis, published in 1685, is the first unequivocal description of the devastating consequences of restless legs syndrome (RLS).1 However, it was not until 1945 that the clinical features of RLS were defined by Karl Ekbom, singling it out as a distinct clinical entity.2 RLS is characterised by an uncontrollable urge to move the legs due to an uncomfortable or unpleasant feeling, which is worse at night and at rest, and temporarily relieved by movement. Full diagnostic criteria are provided in Table 1. Now, we recognise this disorder as a condition commonly encountered in the general practice setting with evidence-based therapeutic options supported by large, well-conducted clinical trials.

| Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for restless legs syndrome |

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders Third Edition63 and the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group23 define five essential RLS diagnostic criteria:

- An urge to move the legs, usually accompanied by or thought to be caused by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs

- Symptoms begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity, such as lying down or sitting

- Symptoms are partially or totally relieved by movement, such as walking or stretching, at least as long as the activity continues

- Symptoms occur exclusively or predominantly in the evening or night rather than during the day

- The occurrence of the above features is not solely accounted for as symptoms primary to another medical or a behavioural condition (eg myalgia, venous stasis, leg oedema, arthritis, leg cramps, positional discomfort, habitual foot tapping)

|

Subclassification based on symptom burden and clinical course

Stratification of symptoms into categories of intermittent, chronic–persistent and refractory RLS is useful to grade severity and aid in therapeutic decision making

- Intermittent RLS: Symptoms when not treated would occur on average less than twice a week for the past year, with at least five lifetime events

- Chronic–persistent RLS: Symptoms, when not treated, would occur on average at least twice weekly for the past year

|

Supportive or associated features of RLS

- Disturbed sleep

- Periodic limb movements in sleep or wakefulness

- Family history, particularly in early-onset RLS

- Positive response to dopaminergic therapy

|

| RLS, restless legs syndrome. |

Aim

This article explores the epidemiology of RLS and then highlights the pathophysiology and clinical features of RLS that enable an accurate diagnosis to be made. Treatment options and an algorithm are presented that can be used by general practitioners (GPs). Finally, scenarios that might necessitate specialist referrals are outlined.

Epidemiology

RLS is a common sensorimotor disorder, with many epidemiological studies supporting a high prevalence, with RLS estimated to affect up to 12% of adults.3 Clincally significant RLS, defined as moderate to severe disease occurring at least twice a week, is also common and seen in 2.7% of adults.4 This figure, however, is not uniform across countries. For instance, studies consistently report that RLS is more common in Europe (especially Scandinavia) and North America than in Asia.3 Furthermore, the reported prevalence differs between studies when a criterion for RLS severity is included.4 The only epidemiological data in Australia come from the parents of the Raine study cohort.5 In that study, 3.7% of male subjects and 2.2% of female subjects fulfilled the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group diagnostic criteria (2003) with symptoms five or more times per month involving moderate–severe distress.5 The onset and severity of RLS increases with age, and the condition occurs twice as more commonly in women, although the risks are equivalent between men and nulliparous women, indicating pregnancy is a significant contributor.6 Renal failure leading to dialysis is a significant risk factor for RLS, and the presence of RLS in patients on dialysis is associated with higher mortality in this population.7 Interestingly, although kidney transplants reverse RLS within days to weeks,8 dialysis has not been shown to improve the symptom burden significantly.9

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathophysiology of RLS remains incompletely understood, although, critically for patients, they can be reassured that it is not a neurodegenerative disease.10 RLS frequently occurs in families, with monozygotic twin concordance ranging between 54% and 83%.11 The mode of inheritance is often autosomal dominant,12 especially with a young age of onset.13 Genome-wide association studies have now shown there to be more than 20 implicated loci.14 Dopaminergic dysfunction is a key trait in RLS,15 although, contrary to popular belief, it is not simply a case of central nervous system dopaminergic deficiency, despite the improvement patients see with dopaminergic agents and dopamine agonists.16 Iron deficiency has been associated with RLS since its early description by Ekbom,17 and relates to brain iron deficiency rather than serum iron deficiency, which only occurs in 25–44% of RLS patients.18 This is supported by the finding of low iron levels in neuropathological samples, on brain imaging with magnetic resonance imaging and functional magnetic resonance imaging (particularly in the substantia nigra and putamen) and in the cerebrospinal fluid (ferritin).15,19 Other causes of anaemia by itself (ie the absence of iron deficiency) are not commonly associated with RLS.20 Pregnancy is often associated with transient RLS.21 Symptoms are most likely to occur in the third trimester and usually resolve around the time of delivery. Interestingly, over half the cases of pregnancy-related RLS did not have a prior history of RLS, although the development of pregnancy-associated RLS increases the risk of developing chronic persistent RLS.22

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of RLS is clinical and there are established diagnostic criteria that include five essential and supportive features (Table 1).23 Polysomnography is not routinely used but, when performed, might show repetitive lower limb muscular contractions, known as periodic leg movements (PLMS), in 70–80% of patients with RLS;24 however, PLMS are also commonly seen in the general population (especially the elderly),25 in other sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, narcolepsy and REM behaviour disorder, and in non-sleep disorders including Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies.26,27 Being a sensorimotor disorder, the hallmark symptom of RLS is an uncomfortable or unpleasant urge to move the legs (and, in some circumstances, involving the arms). It is important to note that this sensation is not always painful or uncomfortable,28 and that patients can use different descriptors to explain the symptoms. Common terms include ‘need to move’, ‘crawling sensation’, ‘restless’, ‘twitchy’ and ‘legs want to move on their own’.

Questionnaire symptom scales, such as the International RLS Study Group rating scale (IRLSSG), can be a useful adjunct in deciding when to treat and monitoring the response to treatment.29

Differential diagnoses

There are many mimics of restless legs, and these must form the differential diagnosis and be carefully excluded prior to making the diagnosis of RLS. These mimics include leg cramps, positional discomfort, myalgia, venous stasis, leg oedema, arthritis and habitual foot tapping. Disturbed sleep is common and might be the sole reason for attending primary care, with sleep onset and maintenance complaints reported in up to 90% of patients with RLS.30 Although daytime fatigue and sleepiness are common complaints, the expected level of daytime somnolence is lower than expected for the degree of sleep disturbance, suggesting a degree of hyperarousal in RLS.31 The natural history of RLS has been established by cohort studies. Although mild, intermittent forms of RLS symptoms might wax and wane over time, whereas severe RLS symptoms appear to be more persistent with less chance of spontaneous remission.32

A careful review of medications should be undertaken. Commonly implicated drugs that might precipitate or exacerbate RLS include antihistamines (particularly the sedating ones), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and dopamine antagonists, such as metoclopramide.33 Of the antidepressants, mirtazapine appears to have the strongest association with RLS,34 whereas bupropion appears to be far better tolerated.35,36 Case studies have suggested that lithium might induce RLS.37

Investigations

It is essential that both a full blood count and fasting iron studies (including ferritin and transferrin saturations) are ordered, because iron deficiency can be associated without anaemia itself. Electrolytes, urea and creatinine (EUC) should be ordered to exclude clinically significant kidney disease, and a pregnancy test should be ordered in premenopausal women. If the clinical history and examination reveal neuropathy, then screening for a cause should be performed, including diabetes, hypothyroidism, vitamin deficiencies (B12and folate), autoimmune conditions and alcohol misuse, as indicated.

Management

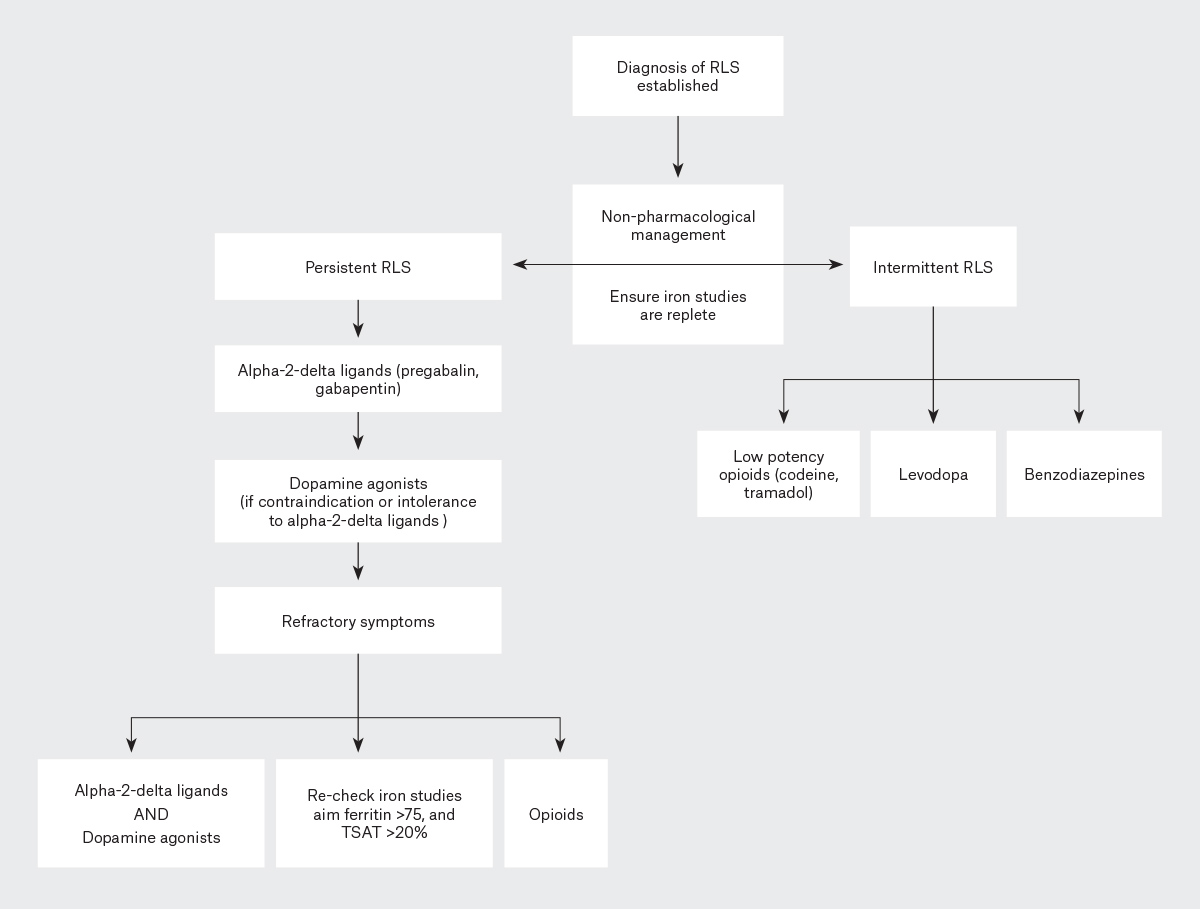

Both non-pharmacological (Table 2) and pharmacological (Table 3) management approaches are essential in the management of RLS. The severity and frequency of RLS symptoms should be established, because this helps guide the choice of therapy (Figure 1). Intermittent RLS is commonly described as symptoms occurring less than twice a week. Conversely, chronic persistent RLS occurs, on average, at least twice weekly. For mild to moderate symptoms, non-pharmacological approaches themselves might be sufficient, and might limit the requirement for dose escalation in patients with moderate to severe RLS, although the overall quality of evidence is low.38–40 Magnesium is widely viewed by the public as an essential treatment for RLS, but a recent well-conducted systematic review found no conclusive evidence to support its widespread use by the public.41 Furthermore, although there appears to be a potential relationship between the presence and severity of RLS and vitamin D deficiency, the evidence for vitamin D supplementation to manage RLS appears mixed; nevertheless, it should be considered.42

| Table 2. Non-pharmacological strategies in RLS |

- Iron replacement when indicated (aiming for ferritin > 75 µg/L, and/or transferrin saturation > 20%)

- Avoidance of caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine

- Consider the effect of medications that might exacerbate symptoms (SSRIs, SNRIs, neuroleptics, dopamine-blocking antiemetics)64

- Alerting activities (eg, video games, crosswords)

- Consider conditions and factors that might exacerbate symptoms, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, shift work, insufficient sleep

|

| RLS, restless legs syndrome; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs, serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors. |

Figure 1. Treatment algorithm for the management of intermittent and persistent restless legs syndrome (RLS). Click here to enlarge

TSAT, transferrin saturation.

Iron repletion is a cornerstone of management in RLS. Consensus opinion suggests targeting ferritin levels >75 µg/L and/or aiming for transferrin saturations >20%.43,44 The latter is important to measure because ferritin might be artificially elevated in the setting of an acute phase response.45 A common oral iron regime is 325 mg ferrous sulfate (65 mg elemental iron) in combination with 100–200 mg vitamin C to enhance absorption. Intravenous iron is recommended if ferritin is close to 75 µg/L due to the inverse correlation between oral iron absorption and ferritin levels.46 It is worth noting that the response to oral and intravenous iron is not immediate, and might take one to three months to see clinical improvements.47

Pharmacological management

Levodopa plus a DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (either carbidopa or benserazide) is a reasonable option to treat intermittent RLS symptoms (ie symptoms occurring less than once or twice a week) but is not recommended as a chronic treatment due to the high risk of tolerance and augmentation (drug-induced worsening of RLS; discussed later).48 Rebound of symptoms in the early morning occurs in 20–35% of patients taking levodopa agents,49 which might be mitigated, in part, by the addition of controlled-release formulations.50 Lastly, low potency opioids such as codeine (30–90 mg) or tramadol (50–100 mg) can be effective for intermittent RLS but may have side effects including nausea and constipation.51

Benzodiazepines might be used in patients with intermittent symptoms, particularly in patients who suffer from sleep initiation insomnia. Clonazepam is the most studied of all the agents, although its long-lasting hypnotic and sedative effects might limit its use.51

Dopamine agonists (Table 3) are effective in managing chronic persistent RLS, defined as symptoms occurring at least twice weekly and causing moderate to severe distress, thus justifying consideration of daily therapy. Once considered first-line therapy, expert guidance suggests that the alpha-2-delta ligands should be trialled first, unless there are significant contraindications.51 This recommendation comes from the increased recognition of augmentation and impulse control disorders that might complicate the use of dopamine agonists. Pramipexole is the only agent on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), whereas ropinirole and rotigotine patch are listed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Doses (of pramipexole, rotigotine and ropirinole) used for RLS are typically lower than those required for the management of Parkinson’s disease because higher doses are associated with an increased risk of augmentation.52 Common side effects include nausea and lightheadedness, which usually resolves after 10–14 days. Daytime sleepiness and sleep attacks might occur with higher doses. Augmentation and impulse control disorder are two major side effects that have led to guidelines moving away from dopamine agonists as first-line therapy. Augmentation is defined as a worsening of RLS symptoms after an initial positive response, with symptoms becoming more severe, often occurring earlier in the day and sometimes spreading to the arms/trunk in progressive cases.53 With pramipexole and ropinirole, the rate of augmentation is around 40–70% over a 10-year period,54,55 reducing to 36% with the rotigotine patch.56 Because augmentation is a dose-dependent effect, maximum recommended doses should not be exceeded. If augmentation occurs, specialist consultation is recommended. Various management strategies include switching to a non-dopamine agonist agent, dose splitting or the use of controlled-release formulations. If dopamine agonists are discontinued, they should be tapered off gradually, otherwise severe withdrawal effects might ensue.51 Impulse control disorder manifests as pathological gambling, hypersexuality or compulsive shopping, with a rate of occurrence between 6% and 17%, commencing on average nine months after commencement of the dopamine agonist.57

| Table 3. Management of chronic persistent restless legs syndrome (symptoms occurring two or more times a week)51 |

| Drug |

Starting daily dose |

Usual daily range |

Common adverse effects |

| Alpha-2-delta ligands (preferred first choice) |

| Gabapentin |

300 mg |

600–2400 mg |

Sedation, confusion, falls, dizziness, headaches, dependence/abuse, oedema, weight gain, increased risk of suicidal thoughts, respiratory depression |

| Pregabalin |

75 mg |

75–450 mg |

| Dopamine agonists |

| Pramipexole |

125 µg |

250–750 µg |

Nausea, vomiting, hypotension, sleepiness, impulse control disorders

High rates of augmentation might limit use |

| Ropinirole |

25 µg |

50–2000 µg |

| Rotigotine patch |

1 mg |

1–3 mg |

| Start at lowest dose and titrate up every three to seven days as required. |

Alpha-2-delta ligands (pregabalin, gabapentin and gabapentin enacarbil; Table 3) are recognised as the first-line treatment for chronic persistent RLS due to their comparable clinical efficacy coupled with a lack of augmentation and impulse control disorder.58,59 In Australia, none of these agents is listed on the PBS or approved by the TGA for this indication, therefore their use is off-label. Gabapentin enacarbil, the extended-release prodrug of gabapentin, is currently not available in Australia. Dosage should occur 1–2 hours before the usual onset of symptoms. Common adverse effects include dizziness, somnolence, unsteadiness and cognitive disturbances, occurring more frequently in older patients. Caution must be exercised in prescribing these agents in patients with an increased risk of side effects, such as excessive weight, comorbid severe depression, dependence issues and compromised respiratory reserve, particularly in combination with opioids.51 Notwithstanding, these agents are now favoured as first-line therapy, and might be particularly advantageous in patients with comorbid insomnia, peripheral neuropathy or anxiety.60

Opioids might be useful for refractory RLS, defined as persisting symptoms despite therapy. This might occur due to the natural history of the condition, with a reduction in the efficacy of the first-line agents, augmentation or drug-associated side effects.51 Abuse potential is low in patients without a history of substance abuse, although due to the well-known side effect profile of these high-potency agents, opioids should only be used in treatment-refractory cases. Low-potency agents should be trialled first, but most patients will eventually require higher-potency agents such as oxycodone/naloxone, which has the greatest evidence supported by data from randomised control trials.61,62 Patients should be referred to a sleep physician or neurologist prior to the commencement of any opioids.

Conclusion

RLS is a very common and debilitating disorder, characterised by an overwhelming urge to move the legs, often associated with unpleasant sensations. Known risk factors include pregnancy, end-stage renal failure on dialysis, iron deficiency and certain exacerbating medications. Although the underlying pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, there is strong evidence on the role of iron and the need for supplementation targeting ferritin levels ≥75 mg/L, and/or transferrin saturations ≥20%. Recent evidence supports a move away from dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole) as first-line agents due to the significant risk of augmentation, as well as impulse control disorders. Alpha-2-delta ligands have been shown to be equally effective, although careful patient selection is required.

Key points

- RLS is a sometimes distressing but common sensorimotor disorder characterised by the universal urge to move the legs.

- RLS should be distinguished from commonly occurring mimics, which must remain on the differential diagnosis.

- Brain iron deficiency might be a driving factor, with serum concentrations poorly correlating with brain iron concentrations. Iron repletion is a cornerstone in the management of RLS, targeting ferritin >75 µg/L and transferrin saturation >20%.

- Management involves both non-pharmacological and pharmacological options, such as alpha-2-delta ligands, non-ergot dopamine agonists, benzodiazepines, dopaminergic agents and opioids.

- The alpha-2-delta ligands (gabapentin and pregabalin) have been shown to be as effective as dopamine agonists, but with significantly reduced rates of augmentation, and, unless contraindicated, are now considered first-line therapeutic agents for chronic persistent RLS.