Diet plays a key role in the onset and progression of chronic disease and is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor.1 However, dietary guidelines for optimal health, nutrition advice and public health messaging focus on diet quality and quantity (what and how much), with no advice on timing of food intake (when to eat).2,3

In modern society, the 24/7 work and social lifestyle leads to erratic eating patterns. Furthermore, Australian adults generally have poor quality diets. Less than 9% of adults eat the recommended intake of vegetables, and only half eat enough fruit, whereas the intake of discretionary (‘junk’) foods accounts for around 35% of the average energy intake.4 When paired with a poor-quality diet, inadequate sleep and a sedentary lifestyle, extended and erratic eating patterns lead to chrono-disruption. Humans have an internal 24-hour circadian clock that synchronises physiological and biochemical processes to the external environment of a light/dark cycle, the sleep/wake cycle and food availability.5 An intricate, bidirectional relationship between the circadian clock and metabolism contributes to metabolic homeostasis.1,6 When the relationship is ‘desynchronised’ or disrupted, there are health consequences. Chrono-nutrition (interactions between what, when and how much) can improve circadian alignment to mitigate the burden of obesity and diet-related chronic diseases.5 That is, confining eating to a 6–12-hour window each day (time-restricted eating [TRE]) has been shown to be efficacious and feasible for adults, aligning intake with the circadian rhythm.1,5,7

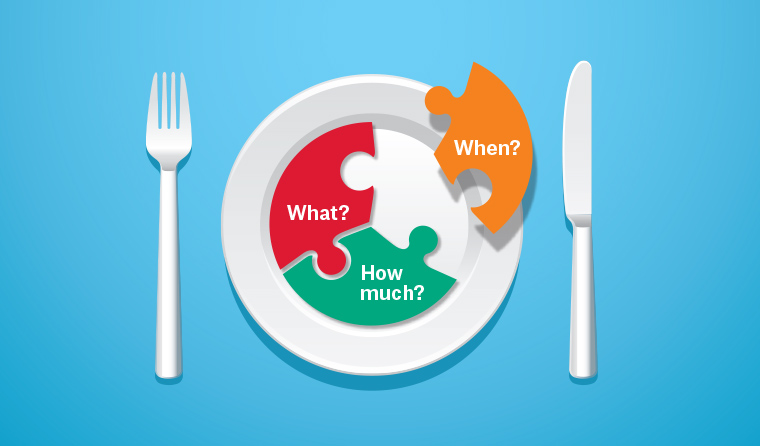

The novel concept of chrono-nutrition through TRE describes that when we eat might be as critical for chronic disease prevention and management as what and how much we eat. When we eat is the crucial missing puzzle piece in practice (Figure 1). TRE emphasises the timing of meals in alignment with diurnal circadian rhythms, permitting dietary intake during an approximate 6–12-hour eating window each day and causes energy restriction through reduced intake of discretionary foods.7 This leads to modest weight loss and dietary intake more closely aligned to the Australian Dietary Guidelines, all with no specific diet quality advice.2 However, metabolic health improvements following TRE have been shown independent of reduced energy intake and weight loss.8 Therefore, when we eat might be a powerful intervention tool.

Figure 1. Diet considerations for chronic disease prevention and management. ‘When’ to eat is the missing puzzle piece.

Dissemination of dietary guidelines and nutrition advice requires extensive nutrition knowledge by trained professionals and a significant time commitment from both the patient and the practitioner. For chronic disease prevention, specific dietary consultations might also come with significant out-of-pocket expenses. TRE is a simple and easily disseminated dietary approach that is likely to be a highly feasible and acceptable tool in primary healthcare. General practitioners (GPs) are critical to managing the health of individuals who are overweight and at risk of chronic disease, and individuals expect to receive nutrition advice from their GP.9 GP-reported barriers to providing nutritional advice to patients include ‘lack of time’ and ‘inadequate training’.10 TRE is an uncomplicated health message that is simple for primary health carers to impart. It might also be a useful adjunct tool before a patient has had the opportunity to engage with an Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD) or for those unable to access specialist help (eg in remote and rural Australia). Additional benefits of TRE include that it does not require changes in usual purchasing habits, meaning it might be more accessible to those with low socioeconomic status. Thus, TRE has strong potential to be rapidly transferable to primary healthcare and at the population level to assist a growing number of individuals at risk of chronic disease. Focusing on when to eat is an attractive, easy-to-adapt and scalable treatment approach involving simple limits around temporal intake of food.

However, TRE and chrono-nutrition is still an evolving area of research, and its long-term effects and suitability for various populations and practitioners are not yet fully established. The ideal window of time for eating is still to be determined in the literature; however, earlier intake appears to be more beneficial (ie eating dinner as early as feasible for the individual). It is advised that this approach is adopted with an open mind and that the six guiding principles in Table 1 are followed as the research continues to develop.

| Table 1. Guiding principles for chrono-nutrition in general practice |

| Guiding principle |

Explanation |

| Evidence-based practice |

As healthcare professionals, GPs base recommendations on evidence-based practices and peer-reviewed research. While some studies have shown promising results regarding chrono-nutrition, more extensive and rigorous research is needed to establish the long-term benefits. Current trials in the Australian population are under way (NCT04762251 and ACTRN12620000453987). The design of these trials considers the practical application and, therefore, is in line with the Australian Medicare Rebate Scheme for Chronic Disease Management Plans |

| Individualisation (consider comorbidities and health conditions) |

Nutrition is a highly individualised aspect of healthcare. People have unique needs, health conditions and lifestyles. This variation needs to be considered when assessing the appropriateness of chrono-nutrition for individuals. GPs should be particularly cautious when recommending any specific dietary approach, including chrono-nutrition, to patients with chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases or eating disorders. These conditions often require individual dietary management, and any specific dietary changes should be made in consultation with an APD |

| Patient education |

If GPs choose to discuss chrono-nutrition with their patients, it is essential to provide balanced and accurate information. Patients should be educated about the current state of research and potential benefits but also the emerging nature of the work and the limitations to date |

| Holistic approach |

Nutrition is just one aspect of overall health and wellbeing. GPs should emphasise a holistic approach to patient care that includes regular exercise, stress management, adequate sleep and other lifestyle factors |

| Collaboration with APDs |

GPs can work in collaboration with APDs who have specialised knowledge and training in nutrition. Dietitians can provide personalised nutrition advice and help patients make informed decisions about dietary choices |

| Monitoring and evaluation |

If a patient decides to try chrono-nutrition, it is important to monitor progress and assess the effects on their health. Regular follow-ups can help determine the effectiveness and safety of the approach for that individual |

| APD, Accredited Practising Dietitian; GP, general practitioner. |

In conclusion, although chrono-nutrition through TRE is a promising intervention and evidence is continuing to emerge about the potential benefits, it is not yet established as a standard dietary recommendation for all individuals. GPs should approach this concept with a critical eye, consider individual patient needs and collaborate with nutrition experts to ensure the best possible care for patients. As the research progresses, more evidence is likely to emerge regarding the benefits and risks of TRE, particularly in the long term, which can help inform future clinical practice.