I do it (using e-cigarettes), but it’s because I’ve tried to quit and I couldn’t think straight I had the worst ever headaches of my life and I found it to be much too difficult to quit. (17-year-old boy, metropolitan South Australia, independent school student)1

Over the past decade, the use of e-cigarettes has increased among young Australians. In 2017, 14% of adolescents reported having used e-cigarettes at least once.1 In 2022, a New South Wales study suggested that e-cigarette use had increased among adolescents and that 32% had used e-cigarettes at least once.2 In 2022, a South Australian study suggested that 66% of adolescents had used e-cigarettes at least once.3 Although there has been an increase in dual e-cigarette and tobacco use in young people, there has also been an increase in exclusive e-cigarette use in young people who have never used tobacco – a new generation of nicotine users.4

E-cigarettes are battery-powered devices that heat liquid to a vapour to inhale. The liquid contains water, propylene glycol and glycerine. Most contain nicotine as well as a varying and wide variety of other potentially noxious chemicals, including formaldehyde, solvents and heavy metals.5 Common flavours used in e-cigarettes include fruit, lolly, mint, menthol and tobacco.6 Sweet flavours are associated with higher subjective reward5 and appear to influence uptake and continuation of e-cigarette use in young people.7 Although some of the additives for flavour have been widely used in food and beverages, their safety when vapourised and inhaled has not been assessed.5

Currently, it is illegal to sell e-cigarettes containing nicotine without a prescription in Australia. However, most e-cigarettes sold without prescription contain nicotine even when this is not a listed ingredient.8 Many young people use disposable e-cigarettes (with significant environmental effects),9 which are cheap, with prices ranging from AU$5 for disposable devices to $15Young people might be to $75 for reusable devices.10 From January 2024, the Australian Government rolled out new regulations to control the importation, manufacture and supply of e-cigarettes. These are likely to affect young people’s access to e-cigarettes, as disposable devices are banned and access is limited to sale in pharmacies on prescription. Although all devices remain unapproved, they must comply with Therapeutic Goods Administration regulations.10

Young people (adolescents aged 12–17 years and young adults aged 18–25 years) might start using e-cigarettes for a variety of reasons, including peer use,11 curiosity11 and boredom12 or to manage their mental health.12 Young people find flavoured e-cigarettes appealing13 and might not realise that these contain nicotine14 or that this can lead to nicotine dependence.5 Nicotine is a highly dependence forming agent,15 and the developing adolescent brain might be more vulnerable to developing nicotine dependence, with signs of dependence possibly developing before daily use.16

Addiction,12 withdrawal symptoms,17 seeing others use e-cigarettes12 and embarrassment about being seen as addicted18 are barriers to changing e-cigarette use. In addition, peer influence and easy access,12 attractive flavours,7 convenience and discreetness of e-cigarette use19 are enablers of continued use. Conversely, lack of awareness,19 apathy or low levels of concern regarding e-cigarette risks,18 lack of motivation12 and low confidence in being able to stop20 are barriers to cessation of use.

There is controversy over the role of e-cigarettes preventing or leading to tobacco use.5,21 Although the long-term risks of e-cigarette use are not clear,22 it is possible that it is safer than tobacco use.21 However, their use has been linked to cognitive and mental health issues in adolescents and young adults,23 and anecdotally, increasing numbers of young people are struggling to cease use of e-cigarettes.1,24 General practitioners (GPs) are important and trusted health professionals for young people seeking help with e-cigarette cessation.

Aim

The aim of this article is to provide Australian GPs with the tools to support young people (adolescents aged 12–17 years and young adults aged 18–25 years) who seek help with e-cigarette cessation.

Helping adolescents and young adults change vaping

Assisting young people to change behaviours is an important role for GPs (Box 1). GPs need to keep the young person’s developmental stage in mind and adjust the consultation accordingly.25 Although some young people might wish to cease e-cigarette use due to health concerns,12 including concerns about dependence and addiction,19 the literature suggests that they might also want to cease to improve sports performance12 or because they perceive that e-cigarettes are ‘not cool’ and not sanctioned by their peers11,19 or parents.11,26 Cost is often an important factor,11,12,19 as is the perception that young people are being manipulated by a profit-making industry.19 The lack of trustworthy available e-cigarette information is another factor.19 Young people want credible, independent evidence-based information.18,27 GPs are experienced in helping young people change behaviour and can ensure the information provided is health and evidence based.

| Box 1. Case study |

| You’ve treated Nate, aged 17 years, and his family in your practice since he was born. He presents today with his mum, Tara. She explains that she has been very concerned about Nate as he seems irritable and distracted. She got a call from Nate’s school principal, who told her that Nate was found using an e-cigarette in the school toilets. Tara sat down with Nate to ask him what was happening, and he told her he’d been using e-cigarettes for about 9 months. At first it had been for a bit of fun, but he’d found himself using more and more, particularly with the stress of his year 11 exams. Nate explains to you that he has tried to change this but feels irritable, anxious and stressed. He feels trapped and wants to stop. He asks, ‘Can you help me, doc?’ |

Opportunistic screening for e-cigarette and tobacco use is suggested for all young people seen by GPs. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners suggests asking every person aged 10 years and above about smoking,28 and international clinical guides suggest asking about e-cigarette use from age 11 years.25,29,30 (See Box 2 for suggestions on how to ask)

| Box 2. Asking and tailoring your response |

|

‘Do you use e-cigarettes?’

‘Tell me about your e-cigarette use?’

‘Have you used e-cigarettes in the last month?’

‘Are you worried about your e-cigarette use?’

‘Would you like to change this?’

How to respond

If the young person is not using e-cigarettes, congratulate them and encourage continued non-use.

If the young person doesn’t wish to change their use, say:

‘Ok, I understand. However, I am concerned about your use. If you want any help with this in the future, please ask me.’

If the young person is using e-cigarettes and wishes to change this, assess the level of use. Ask:

‘How many days in the last month have you used e-cigarettes?’

‘How soon after waking in the morning do you have your first e-cigarette?’

|

There are complexities in assessing the level of nicotine use. The e-liquid and device might not accurately list the presence of nicotine or its concentration. The number of puffs per day can vary, be influenced by context (ie less use in school)31 and be difficult to recall. Onset and peak nicotine concentrations are variable and affected by the type of nicotine used (free base or salt), the nicotine concentration of the e-liquid, the device used and how the vapour is inhaled by the user.22

Assessing loss of autonomy and dependence

The modified Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (m-HoNC) is a validated tool32,33 that assesses the loss of autonomy or level of dependence in adolescents and can also be used in young adults (Box 3).34 The m-HoNC was developed to assess cigarette nicotine dependence, and research suggests it is also valid for e-cigarette dependence.35 Understanding the level of dependence helps with treatment planning.

Asking how soon after waking in the morning a young person uses an e-cigarette (Time To First Vape, TTFV) is a useful and quick way of assessing dependence.33,36 Use within five minutes of waking suggests a very high level of dependence and within 30 minutes of waking, a high level of dependence.33

| Box 3. How to assess the quantity and level of loss of autonomy and dependence: The m-HoNC |

- Have you ever tried to quit, but couldn’t?

|

Y/N |

- Do you vape now because it is really hard to quit?

|

Y/N |

- Have you ever felt like you were addicted to vapes?

|

Y/N |

- Do you ever have strong cravings to vape?

|

Y/N |

- Have you ever felt like you really needed a vape?

|

Y/N |

- Is it hard to keep from vaping in places where you are not supposed to, like school?

|

Y/N |

| When you tried to stop vaping (or when you haven’t used vapes for a while) ... |

|

- did you find it hard to concentrate because you couldn’t vape?

|

Y/N |

- did you feel more irritable because you couldn’t vape?

|

Y/N |

- did you feel a strong need or urge to vape?

|

Y/N |

- did you feel nervous, restless or anxious because you couldn’t vape?

|

Y/N |

| A yes to any question indicates that the young person is experiencing a ‘loss of autonomy’ over their use and some dependence on nicotine. Each yes indicates increasing dependence. |

m-HoNC, modified Hooked on Nicotine Checklist; N, no; Y, yes.

Adapted with permission from Bittoun.36 |

What young people want

Research suggests that young people want to build skills that assist them to manage e-cigarette cessation.27 These include skills to manage poor concentration and a short attention span through the withdrawal period17 as well as stress and anger management27 and developing a positive mindset.17

Young people might be keen to use apps,20,37 social media18 or websites37 to support cessation. Free smartphone apps specific for e-cigarette cessation are available. Although they might be useful, they have only moderate ratings on The Mobile App Rating Scale in terms of ‘engagement, functionality, aesthetics, information quality, and subjective quality’.38 Most are American and might not use language that speaks to young Australian people. ‘My QuitBuddy’ is an Australian app that focuses on tobacco cessation but might be useful for e-cigarette cessation.39

Working with young people requires GPs to respect autonomy and flag what worked and what did not to help young people build self-efficacy.

25,29 Some young people might not want to stop completely and are looking for ways to cut down.

17,18 Although this can work for some, others might find that their use rebounds when under stress, and they might need to stop completely. One tapering option that young people suggested was the gradual reduction in nicotine concentration in the e-cigarette device to aid cessation.

17 It is not clear how effective this is.

40 Australian authorities do not currently support the prescription of e-cigarettes to assist young people aged <18 years to cease either tobacco or e-cigarette use (this might change in the future).

41

Some young people might be pre-contemplative and not wish to change their e-cigarette use. In this case, a possible approach is to document the use, suggest the young person weigh up the pros and cons, and offer assistance in the future.

Families are an important influence for young people and can take a role supporting e-cigarette cessation.

25 If others in the household smoke or use e-cigarettes, it might be helpful for them to also change their use. Agreeing to ban the use of cigarettes or e-cigarettes in the home by all family members and visitors and disposing of all devices might assist with cessation.

33,36,42,43

Support from friends18 or peer mentoring have been suggested by young people to help with cessation. The research to date suggests that the peer mentor needs lived experience of e-cigarette cessation, an ability to share their personal experiences, to give relatable anecdotes and to provide emotional support.18,44,27 Although adolescents were happy for an intervention to happen at school, they did not want their teacher to run this, preferring a peer or outside independent, credible expert.18

The 5Ds (delay, distract, drink water, deep breathing and discuss your cravings with a support person) were suggested.33 Distraction techniques (eg gaming or hobbies),17 engaging in other activities45 and exercise were thought to be useful (Box 4).27

| Box 4. Assisting young people to change e-cigarette use |

- Ask the young person what they see as the ‘good things’ and the ‘not so good things’ about using e-cigarettes and explain the benefits of e-cigarette cessation.

- Explain the benefits of e-cigarette cessation.

- Explain the role of nicotine and dependence – completing the m-HoNC can assist with this.

- Seek support from the household; smoking/vaping bans in the home might help.

- Use a strength-based approach, support personal choice and ask the young person what they think would help.

- Give a suite of options, including advice about coping with cravings, distraction techniques, the 5Ds, avoiding high-risk situations, preparing for lapses, setting a quit date and reducing caffeine use.

- Consider Quitline, apps, online options and NRT.

- Review and follow-up.

|

| 5Ds, delay, distract, drink water, deep breathing and discuss your cravings with a support person; m-HoNC, modified Hooked on Nicotine Checklist; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy. |

Mental health co-morbidity is common in young people, so it is important to take this into consideration.25

Pharmacological options

There is little evidence to support the pharmacological approach to adolescent smoking cessation and no evidence for effective pharmacological treatments to assist young people in ceasing to use e-cigarettes. As a result, evidence must be drawn from what is available for adults. It is possible that adult pharmacological smoking cessation options might also work for e-cigarette cessation in young people.

Nicotine replacement therapy

Available clinical guidelines encourage the use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)25,29,30,33,41,42 and stress the importance of concomitant behavioural interventions. NRT is safe to use from age 12 years,46 and it can be useful to start NRT prior to the quit date.33 NRT acceptability for young people is mixed,18,37,47 and compliance can be an issue. Ask the young person if NRT is acceptable and if they want to try it (Box 5).

| Box 5. Case study continued |

|

Nate has been using e-cigarettes daily for 4 months. He thinks he takes 100 puffs a day but is not sure. He uses his e-cigarette device within 30 min of waking. He is keen to stop. His girlfriend and his mum and dad are keen for him to stop. You discuss techniques for him to use and suggest that NRT might be useful. He is keen to use distraction techniques, delay his first puff of the day, get back into running, encourage support from his girlfriend and family and try NRT gum. He has just started school holidays and is keen to quit now as he feels this is an easier time to make this change. You explain the ‘chew and park’ use of gum and arrange to see him in 2 weeks.

When you review Nate 2 weeks later, he says he managed to delay his first e-cigarette of the day until lunchtime but is still experiencing cravings. He is keen to try a patch. You suggest increasing his use of gum and add a 21 mg nicotine patch.

You review him 2 weeks later, and Nate has not used e-cigarettes for 10 days. He is very happy with this change. He decides he’d like to use the patch for another 2 weeks and then continue on gum for another 2 weeks.

When you review 1 month later, he has stopped completely and says he is supporting a couple of mates to also stop e-cigarette use.

|

| NRT, nicotine replacement therapy. |

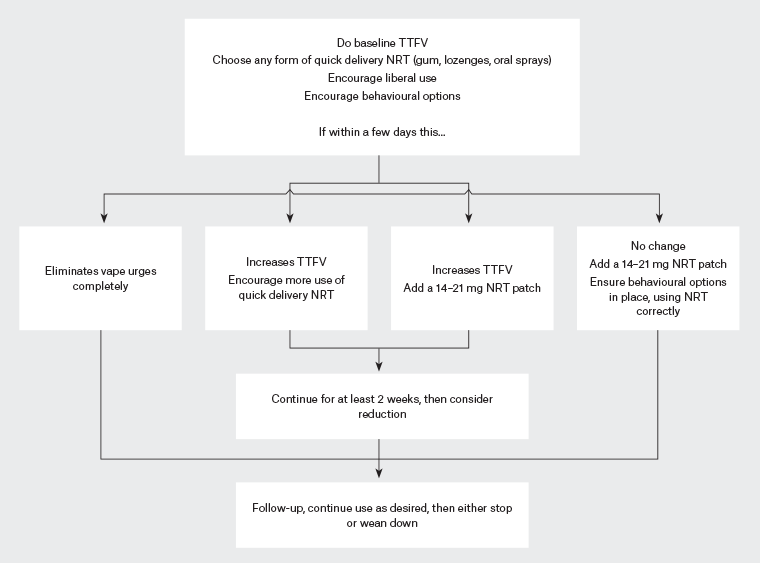

NRT is likely to be more useful in young people with high levels of nicotine dependence. A suggested approach is to start with monotherapy in the form of short-acting options (eg gum, lozenges or oral spray) and encourage liberal use36 (it is suggested that inhalators be avoided as they might mimic and reinforce the hand-to-mouth action of e-cigarettes, which anecdotally might decrease cessation success).29,33 If use of short-acting NRT stops use, congratulate the young person, and encourage use as needed. If this reduces use but does not entirely cease it, consider increasing the frequency of dosing or trying combination therapy by adding long-acting NRT (a 14–21 mg patch) (Figure 1).33,36 Consider the ongoing role of behavioural options.41

Figure 1. Suggested approach to using NRT for young people who want to cease e-cigarette use. Click here to enlarge

Adapted with permission from Bittoun.36

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; TTFV, Time To First Vape.

The use of NRT for e-cigarette cessation is currently considered ‘off label’ in Australia, as this is not listed as an indication by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration. ‘Off-label’ prescribing is not uncommon; however, this aspect needs to be discussed before prescribing.41

Other pharmacological options

Varenicline and bupropion might be used in young adults (aged 18–25 years) with a need to balance risks and benefits.25,29,30,41,42

Review and follow-up

Early review and follow-up are important to support young people to change e-cigarette use.33 Consider referring young people with complex presentations or multimorbidity25 to a youth service, a counsellor with youth expertise or specialist mental health or addiction services.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence to guide the best treatment for young people asking for help to cease the use of e-cigarettes. GPs might see young people asking for assistance and can use a rational approach to assist. This includes assessing the level of nicotine dependence and offering behavioural support and NRT. Family support is important, as is the influence of peers and school for school attendees. More research is needed to better understand the most effective options for e-cigarette cessation for young people.

Key points

- Increasing numbers of young people aged 12–25 years are using e-cigarettes.

- Young brains are at high risk of nicotine dependence.

- Young people aged 12–25 years might seek help from GPs to cease e-cigarette use.

- Existing literature offers a rational approach to assist GPs to help young people cease e-cigarette use.

- A combination of behavioural and pharmacological options might assist.