David Homewood and Ming Hei Fu are the co-first authors.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common solid organ malignancy in men in Australia.1 It is a hormone-dependent malignancy that relies on androgen signalling pathways for carcinogenesis and disease progression. Hormonal therapy that primarily acts to suppress testicular androgens was established as a treatment for prostate cancer by Huggins and Hodges in their Nobel Prize-winning experiments.2 Hormonal therapy to maintain a castrate level of testosterone (<20 ng/dL) (medical castration) has since been a mainstay of prostate cancer therapy, especially in those with metastatic disease. Unfortunately, despite initial responses, patients commonly develop resistance to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and progress to castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).3 This has prompted the development of novel pharmaceuticals that can target androgen receptor (AR) signalling pathways through alternative mechanisms and therefore improve treatment efficacy and survival outcomes.

Aim

This review provides a contemporary update on ADT with further discussion of emerging novel therapies.

Evolution of androgen deprivation therapy

The concept of androgen deprivation as a therapeutic strategy for prostate cancer dates to the era of surgical castration in the mid-twentieth century.2 This approach demonstrated promising results by shrinking tumours and alleviating symptoms.2 Subsequently, medical interventions emerged, which proved equally effective in achieving castrate level testosterone without the use of irreversible surgical procedures.4,5

Where hormone therapies sit in the prostate cancer treatment landscape

Treatment decisions for the management of PCa are stratified by risk (clinical assessment, prostate-specific antigen [PSA], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], histopathology) and presence of nodal disease and metastasis. For low-to-intermediate risk, active surveillance, watchful waiting and surgical management are the mainstays of treatment. In intermediate-to-high-risk localised disease, radical prostatectomy is the standard of care. In highly co-morbid patients with localised disease, metastatic disease, or in many other scenarios, hormone therapies, with or without radiotherapy, can be offered.6

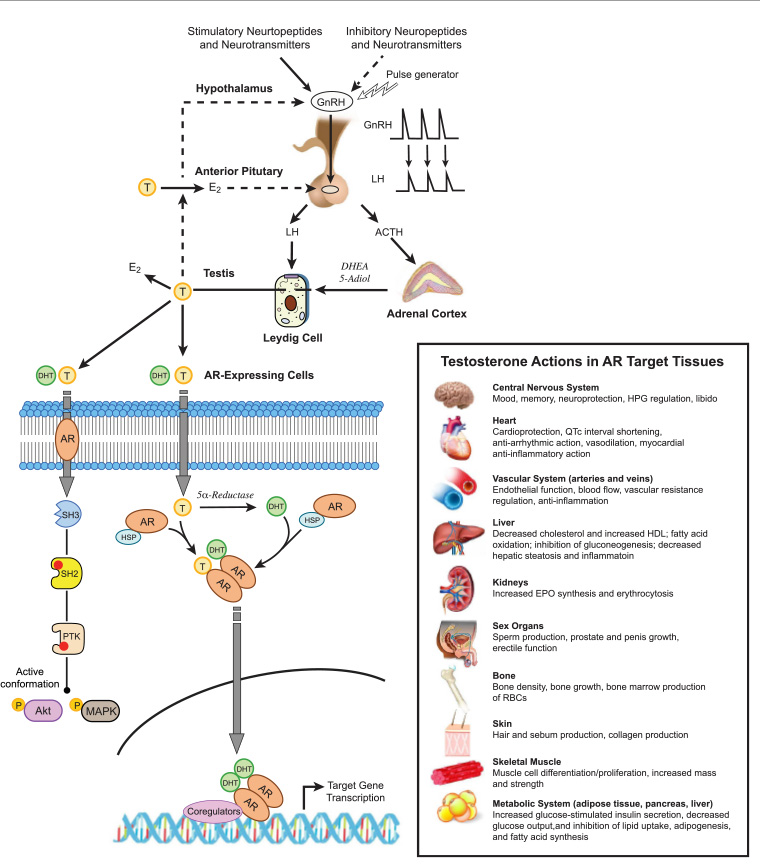

ADT acts through luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH, also known as GnRH) agonism/antagonism, which suppresses the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis to reduce circulating testosterone levels (Figure 1).5,7

Figure 1. Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) medications illustrating the mechanism of action. Click here to enlarge

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; AR, androgen receptor; ARPI, androgen receptor pathway inhibitor; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, estradiol; GnRH, gonadotrophin hormone-releasing hormone; LH, luteinising hormone; T, testosterone.

Refer to the below article (Hauger et al) for other abbreviation definitions.

Reproduced from Hauger RL, Saelzler UG, Pagadala MS, Panizzon MS. The role of testosterone, the androgen receptor, and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in depression in ageing Men. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022;23(6): doi: 10.1007/s11154-022-09767-0, with permission from Springer Nature.

Long-acting LHRH agonists are synthetic analogues that are used as the predominant contemporary modality of ADT (such as goserelin, leuprorelin). Initial injection of LHRH agonists can cause a transient rise (two to seven days) in luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), with subsequent initial surge in testosterone.4 This surge can cause a flare of symptoms (such as bone pain and bladder outlet obstruction);4 however, chronic LHRH exposure results in LHRH downregulation and castration within two to four weeks.6 To mitigate this transient ‘flare’ on initiation of treatment, anti-androgens such as bicalutamide are given.8 To avoid flares entirely, LHRH antagonists were developed.

LHRH antagonists directly bind LHRH receptors, lowering LH and FSH and rapidly reducing testosterone levels without an initial surge.7 However, LHRH antagonists are limited by their pharmacokinetics (as there is currently no long-acting depot, Degarelix requires monthly injections). Both LHRH agonists and antagonists have similar side effect profiles; they both reduce bone density and increase risks of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.6

First-generation anti-androgens and intermittent ADT

First-generation anti-androgens such as bicalutamide, are oral compounds (steroidal and non-steroidal), that directly antagonise the androgen receptor (AR) (Figure 1); they are often used in combination with an LHRH agonist as they reportedly reduce androgen-related side effects such as decreased libido and physical performance.8 Second-generation anti-androgens (eg enzalutamide) are increasingly used in its stead due to superior survival benefit.9

Intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) was proposed as a treatment schedule that can improve quality of life, and an in vivo model suggests that replacing androgens before disease progression could prolong androgen dependence.10 However, its clinical efficacy has been evaluated in eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and two subsequent meta-analyses,11–20 which failed to demonstrate IAD’s non-inferiority. Given this, continuous ADT remains a standard of care.6

ADT resistance and need for novel therapeutics

Unfortunately, once started on ADT, progression to CRPC is almost inevitable within one to eight years, depending on risk factors such as PSA level pre- and post-ADT treatment.3,21 CRPC is defined as biochemical or radiological progression of disease with castrate level testosterone.6 There are multiple mechanisms proposed to explain castrate resistance, commonly divided into AR-dependant (AR gene mutations/amplification, existence of splice variants and adaptive upregulation of androgen receptor co-regulatory molecules) and AR-independent mechanisms.3 In the initial stages, ongoing activation of the AR predominates, which spurred the development of small molecule androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPIs), such as abiraterone, apalutamide, darolutamide and enzalutamide (Table 1).22–31

| Table 1. Novel options for androgen suppression in prostate cancer31 |

| Drug (mechanism) |

Disease state – validating study |

Side effects24–27 |

Administration24–27 |

Drug interactions |

Abiraterone

(CYP17 inhibitor) |

mCRPC – COU-AA-30222

mHSPC – LATITUDE23 |

Mineralocorticoid-related adverse-related events

Neutropenia, anaemia cardiovascular events, transaminitis |

1000 mg daily |

Carbamazepine might decrease abiraterone concentration and an alternative anti-epileptic might be chosen or an abiraterone dose might be increased |

Apalutamide

(non-steroidal ARPI) |

mHSPC – TITAN24

nmCRPC – SPARTAN25 |

Fatigue, hypothyroidism, rash |

240 mg tablet daily |

Apalutamide reduces the concentration of midazolam, rosuvastatin and warfarin, which might require an increase in dose |

Darolutamide

(non-steroidal ARPI) |

nmCRPC – ARAMIS26 |

Headache, fatigue, transaminitis |

600 mg daily or 300 mg twice daily (bd) |

Darolutamide increases rosuvastatin concentration and might cause an increased risk of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis |

Enzalutamide

(non-steroidal ARPI) |

mCRPC – PREVAIL27

mHSPC – ARCHES28

nmCRPC – PROSPER29 |

Cardiac and hepatic toxicity, hypertension, falls, fatigue, hypertension35 |

160 mg daily |

Enzalutamide increases the metabolism of PPIs, midazolam and warfarin and might reduce their clinical effect; a dose increase might be needed |

| ARPI, androgen receptor pathway inhibitors; CYP17, cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; mHSPC, metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer; nmCRPC, non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors. |

Abiraterone inhibits cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (CYP17) within adrenal cells and tumour cells to decrease intravascular and intracellular testosterone, respectively.3 Given its adrenal suppression, it must be given with prednisolone (5 mg once or twice a day).32

Apalutamide, darolutamide and enzalutamide are non-steroidal ARPIs (also known as second-generation anti-androgens) that bind to the ligand-binding region or domain (LBD) of the AR. They prevent androgen translocation to the nucleus and prevent androgen-initiated transcription of DNA.3 Darolutamide is structurally unique with reduced penetrance through the blood–brain barrier.33

ARPIs in non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

Three major phase III trials examined metastasis-free survival in non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) (staged with computed tomography [CT] and bone scan) treated with apalutamide,25 darolutamide26 or enzalutamide29 compared to placebos (Table 1). All trials showed significant metastasis-free survival and overall survival (OS) benefits after >30 months of follow-up.25,26,29

ARPIs in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

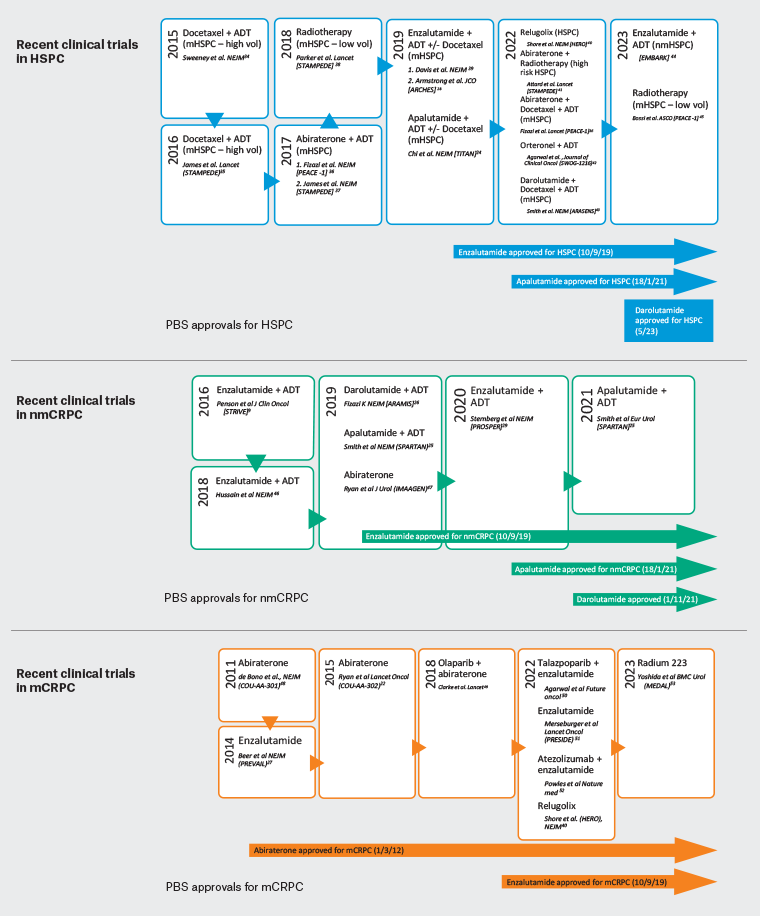

Large phase III, double-blinded studies with abiraterone22 or enzalutamide27 demonstrated improved OS, radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) with reduction in PSA levels and improved quality of life when compared to placebo. As such, these agents are now used in first-line treatment for mCRPC (Figure 2).6,9,22–29,34–53

Figure 2. Recent clinical trials and Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS) approvals for treatments of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) and metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) in Australia.9,22,24–26,28,29,34–47,53 Click here to enlarge

ARPIs in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer

With these successes in mind, ARPIs were tested in the treatment of mHSPC, where treatment was historically limited to ADT±taxane-based chemotherapy.6

Traditional maximal androgen blockade, achieved through combining ADT with a first-generation anti-androgen, lowers circulating androgen levels and directly antagonises the AR simultaneously. It has a minimal survival benefit, but at the cost of increased adverse events and worse quality of life.54

The newer combinations of ARPI+ADT, however, are more effective. When compared to ADT alone, abiraterone use has been shown to increase OS,23 enzalutamide reduced rPFS and death28,35 and apalutamide showed an increase in OS and PFS.24

Although these results are promising, ARPIs are only available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS), with restrictions to staging of PCa (Table 2),30 with a note that if disease should progress while on a novel hormonal therapy, the patient can no longer receive subsidies for the same medication.30 The PBS also limits patients to one novel therapy only in one’s lifetime;30 the choice of initial therapy and the optimal timing of usage is therefore crucial and of much debate among prescribers (common examples are given in Table 3). Importantly, it should be noted that abiraterone acetate is now off patent and generic versions are available, which makes it a more cost-effective option compared to other ARPIs.

| Table 2. Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS) criteria by indication for the systemic pharmaceutical management of prostate cancer30 |

| |

mCRPC |

nmCRPC |

mHSPC |

Cost of private script in AUD (as per PBS) |

| Abiraterone |

- Must be used with corticosteroid

- Must not be used with chemotherapy

- WHO performance status <2

|

|

|

$3442.99 for 60×500 mg tablets |

Apalutamide

|

|

- Absence of distal metastases on medical imaging

- ECOG ≤1

- PSA value doubled within a 10-month period

- Concurrent treatment with ADT

|

Initiated within 6 months of ADT |

$3715.43 for 120×60 mg tablets |

Darolutamide

|

|

- Absence of distal metastases on medical imaging

- ECOG ≤1

- PSA value doubled within a 10-month period

- Concurrent treatment with ADT

|

$3537.77 for 112×300 mg tablets |

| Enzalutamide |

- Must not be used with chemotherapy

- WHO performance status <2

|

- Absence of distal metastases on medical imaging

- ECOG ≤1

|

Initiated within 6 months of ADT |

$3478.58 for 120×40 mg tablets |

| ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; mHSPC, metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer; nmCRPC, non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; WHO, World Health Organization. |

| Table 3. Examples of the new standard of care in antiandrogen therapy |

| Clinical scenario |

New standard of care |

| Metastatic prostate cancer (either de novo or recurrence post prostatectomy/radiotherapy) where no prior systemic treatment has been given (ie hormone sensitive) |

- ADT should be started

- AR pathway inhibitor, such as enzalutamide, apalutamide, darolutamide or abiraterone, should be started

- Docetaxel x six cycles might be considered in higher-risk patients or those with higher volume metastatic disease

|

| Non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (rising PSA despite ongoing ADT and testosterone suppression) and no prior AR pathway inhibitor, with no metastases seen on CT or bone scan (pelvic LN or local recurrence are acceptable) |

- ADT should be continued

- AR pathway inhibitor, such as ezalutamide, apalutamide or darolutamide, should be started

|

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (rising PSA despite ongoing ADT and testosterone suppression) and no prior AR pathway inhibitor, with metastases seen on CT or bone scan |

- ADT should be continued

- AR pathway inhibitor, such as enzalutamide, apalutmaide, darolutamide or abiraterone, should be started (can be used before or after use of docetaxel chemotherapy)

|

| ADR, androgen deprivation therapy; AR, androgen receptor; CT, computed tomography; LN, lymph node; PSA, prostate-specific antigen. |

Cross-resistance between ARPIs

Cross-resistance among ARPIs has been demonstrated in the literature.3 As the mechanisms of abiraterone and enzalutamide differ, Noonan et al55 explored subsequent treatment with these two agents for patients with disease progression on either therapy. A small population was analysed (n=27), and only 11% had a significant PSA decline on subsequent treatment. Many mechanisms of cross-resistance between agents have been suggested, including existence of AR splice variants and ligand-binding domain mutations in the AR.3 Therefore, there is limited evidence on the best sequencing of treatments, but the general guide is to avoid repeated therapy with different ARPIs due to reduced efficacy.

Combination therapy

For mHSPC, the literature has shown that combination therapy, including ARPI, has resulted in improved survival outcomes (Table 4). 24,36,39,43,56,57

| Table 4. Summary of combined ARPI therapies in the treatment of PCa |

| Type of PCa |

ARPI |

Trial |

Intervention |

Outcome |

| mHSPC |

Apalutamide |

TITAN24 |

Apalutamide + ADT |

Reduced death by 35%, delayed castration resistance |

| mHSPC |

Abiraterone |

PEACE-136 |

Abiraterone + ADT + Docetaxel |

- Increased rPFS and OS

- Increase in hypertension rates

|

| mHSPC |

Enzalutamide |

ENZAMET39 |

Enzalutamide + chemotherapy |

Prolonged OS, rPFS |

| mHSPC |

Darolutamide |

ARASENS43 |

Darolutamide + ADT + Docetaxel |

- Increase OS in both low- and high-volume disease

- Prolonged time to resistance

|

| mCRPC |

Enzalutamide |

AFFIRM56 |

ARPI post chemotherapy |

OS increased by 5 months, greater rate of reduction in PSA level by 50%, QoL response rate, PFS, time to first skeletal-related event |

| mCRPC |

Abiraterone/Enzalutamide |

CARD57 |

Cabazitaxel post Docetaxel + ARPI |

Prolonged OS, rPFS increased by 36% |

| ARPI, androgen receptor pathway inhibitors; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; PCa, prostate cancer; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; mHSPC, metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; QoL, quality of life; rPFS, radiographic progression-free survival. |

Large RCTs in this setting demonstrated that ARPI and ADT combined was superior to ADT monotherapy.23,41 Most recently, two randomised studies reported that triplet therapy with ARPI+docetaxel+ADT was superior to docetaxel+ADT doublet therapy.36,43 Guidelines have subsequently been updated to reflect ARPI combination therapy as the standard of care for treatment of mHSPC.6

Common complications of androgen suppression and what to do

Suppressed androgen levels secondary to ADT can cause unpleasant side effects (Table 5).6,31 As the use of ARPIs is not a curative treatment, patients must be counselled on the possible compromise on the quality of life when using ARPIs. Treatment is contraindicated in asymptomatic disease and can result in very short life expectancy (based on non-PCa comorbidities)6 and hypersensitivity to medication. Existing comorbidities are a relative contraindication to hormonal therapy, as the benefit of prostate cancer treatment might not outweigh the increased risk of cardiovascular disease, seizures, diabetes, reduction in bone health or adverse effects.6

| Table 5. Common side effects of androgen suppression and management6,31 |

| Common side effects |

Treatment |

| Hot flushes |

- Lifestyle changes such as avoiding food triggers

- Consider changing to intermittent ADT

- Cyproterone acetate

- Gabapentin

|

| Fatigue |

- Physical exercise and dietary counselling

- Temporary withdrawal of ARPI

|

| Sexual dysfunction |

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

|

| Metabolic effects |

- Baseline + routine check of random glucose and HbA1c, blood lipid levels, LFTs

|

| Depression |

- Antidepressants

- Encourage patient to attend speciality-led multidisciplinary rehabilitation

|

| Osteoporosis |

- Calcium and vitamin D supplement

- Yearly DEXA scan

- Anti-resorptives

|

Abiraterone – hypokalaemia

|

- Low-dose prednisolone

- More frequent monitoring of potassium levels and replace as needed

|

| Apalutamide – hypothyroidism |

- TFTs pre-treatment

- Thyroxine replacement

|

| Apalutamide – skin rash |

- Antihistamines

- Topical corticosteroids

|

| ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; ARPI, androgen receptor pathway inhibitors; DEXA, dual X-ray absorptiometry; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1C; LFT, liver function test; TFT, thyroid function test. |

Hypogonadism secondary to androgen suppression affects skeletal bone health; all patients should be prescribed calcium and vitamin D supplements. It is recommended that long-term ADT patients should be offered dual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans and antiresorptive therapy (eg alendronate, denosumab for those with a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of <–2.5, at high clinical risk of fracture or have a >5% annual bone loss).6

There is limited evidence that shows enzalutamide is associated with seizures.56 Its use should be cautioned for patients with lower seizure threshold, such as a history of epilepsy, long-term alcohol use or other medications that could lower seizure threshold. Patients treated with enzalutamide reported a small increase in fatigue in the first weeks of treatment that stabilises/improves after week 13.58 Falls secondary to fatigue in enzalutamide patients are also more frequent.27 Patients should be counselled on clinical management of fatigue and risk of falls in the initial stages of treatment. The European Association of Urology recommends 12 weeks of supervised exercise for all patients being treated with ADT to reduce fatigue, nausea and dyspnoea. Clinically significant fatigue is also associated with depression, and so patients should also be screened for depression symptoms.6

Apalutamide and darolutamide are newer agents in the market, but initial reports suggest that they might have a more favourable side effect profile compared to other ARPIs. Two of the common side effects experienced by patients taking these agents were hypertension and rash.24,26 Trial data report the incidence of hypertension requiring treatment to be 10–15% and therefore it is important that this be monitored closely following treatment initiation. The incidence of skin rash was reported to be 20–30% in the published trials, but real-world data estimate the incidence to be as high as 50%. The skin reactions can take several forms, but are often a macular or maculopapular rash. These have been managed with topical/systemic corticosteroids and/or antihistamines with good results, but dose reduction or treatment discontinuation might be necessary.24,43

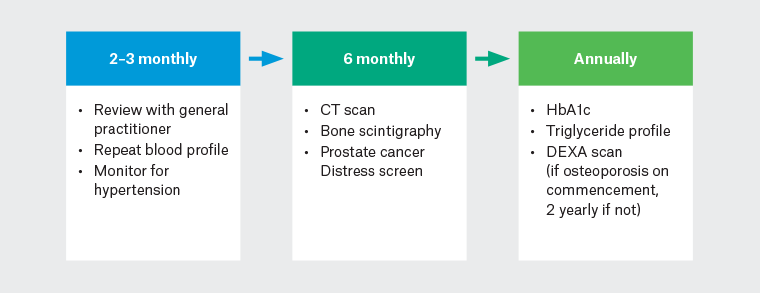

Abiraterone has an alternative mechanism of action and therefore a different side effect profile.3 Through inhibition of steroidogenic enzymes in the testes and extra-gonadal sites, there is also a reduction in glucocorticoid synthesis by the adrenal gland, but an overproduction of mineralocorticoids.32 This can cause fluid retention, hypertension, peripheral oedema and hypokalaemia. To mitigate this, prednisolone is administered along with abiraterone, but this then exposes patients to side effects of steroid excess (eg central adiposity, depression, easy bruising, fractures and muscle weakness).31 ADT and abiraterone are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, hepatotoxicity, diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction, but not overall cardiovascular mortality.59 Treating clinicians and general practitioners (GPs) should highlight red flag symptoms to high-risk patients being treated with ARPIs, and patients should have routine blood tests for monitoring (Figure 3).6

Figure 3. Monitoring suggestions for patients on hormonal therapy.

CT, computed tomography; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1C; DEXA, dual X-ray absorptiometry.

Given the risk of metabolic diseases, patients should have yearly haemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) and triglyceride studies to monitor for diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia (Figure 3).6

Notably, most ARPIs are associated with low rates of adverse events in these large trials; however, patients with a higher Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score (ECOG) tend to experience a higher rate of adverse events and shorter OS compared to patients with a lower ECOG.36,39

Conclusion

Novel androgen receptor pathway inhibitors, in combination with ADT, have shown to have a significant advantage over ADT alone in treating high-risk, advanced prostate cancer patients. Prompt identification and treatment of common side effects of novel therapies is important to ensure maximal treatment compliance.

Key points

- Androgen receptor pathway inhibitors combined with androgen deprivation therapy is the new standard of management for advanced prostate cancer.

- Common indications include previously treated or new, advanced disease, and palliative symptom management.

- There is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and possible reduced seizure threshold.

- Primary care can play an important role in reviewing patients on androgen-deprivation therapy for common side effects