Urinary incontinence is a common presentation in general practice, and it is estimated that 65% of women and 30% of men sitting in a general practice waiting room report some type of urinary incontinence.1 Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is when a patient experiences a leak of urine when there are periods of increased abdominal pressure. SUI is defined by the International Continence Society as ‘the complaint of any involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion (eg sporting activities), or on sneezing or coughing’.2 SUI affects many domains of a person’s life, and a large proportion of SUI can be improved or cured, but SUI is often under-reported secondary to incontinence-related stigma.3 Primary care providers are therefore essential in the assessment and management of SUI.

Aim

The aim of this article is to highlight key diagnostic and management principles of female SUI in general practice and discuss management options.

Pathophysiology and assessment of SUI

SUI is related to weakness of the pelvic floor and urethral sphincter, resulting in leakage of urine with increased intra-abdominal pressure, such as that experienced during exercise, coughing and laughing. The postulated aetiology of SUI includes intrinsic sphincter deficiency and urethral hypermobility, with common risk factors outlined in Table 1.4

| Table 1. Risk factors for stress urinary incontinence |

| Factors increasing intra-abdominal pressure |

Factors altering pelvic floor muscles/ligamentous supports |

| Central obesity |

Multiparity |

| Pulmonary disease/chronic cough |

Instrumented deliveries and increased birth weight |

| Diabetes and metabolic syndrome |

Prior hysterectomy or any pelvic surgery |

| Increased levels of heavy physical activity |

Pelvic radiotherapy |

| Smoking |

|

Other types of incontinence (Table 2) might easily be confused for SUI, and so targeted history and examination is essential (Table 3). Urge urinary incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine associated with the individual reporting the sensation of a sudden, compelling desire to void, and is a common form of urinary incontinence.2 Another less common but important differential of SUI is stress-induced detrusor overactivity (SI-DO). SI-DO is when a patient has stress-related incontinence associated with a sensation of urgency. SI-DO has a clear history of provocative situations (near a bathroom, feet hitting the floor) that trigger high volumes of flooding. It is crucial to distinguish both urge urinary incontinence and SI-DO from SUI due to vastly different treatments; mistreatment can worsen detrusor overactivity and harm patients long term.

| Table 2. Differential diagnoses to consider for causes of urinary incontinence in women |

| Urge urinary incontinence |

Urinary leakage associated with a strong and sudden desire to void |

| Stress-induced detrusor overactivity |

Detrusor overactivity and a feeling of urgency associated with periods of stress |

| Overflow incontinence |

Associated with chronic urinary retention and elevated post-void residual volumes |

| Rare causes |

Fistulas

Ectopic ureteric insertion |

| Table 3. Assessment of a patient with stress urinary incontinence |

| Assessment |

Content |

History

|

- Characteristics of the incontinence

- Type of incontinence (eg stress, urge, mixed, overflow, functional, insensible)

- Exacerbating factors, time course

- Treatment that has been undergone (eg physiotherapy, continence aides, medications)

- Structured patient reported surveys such as the Incontinence Symptom Index6

- Other lower urinary tract symptoms

- Frequency, urgency, urge incontinence

- Weak stream, hesitancy, straining

- Sensation of incomplete emptying

- Nocturia (if this is the predominant symptom, nocturnal polyuria needs to be ruled out)

- Dysuria

- Pelvic pain symptoms (including dyspareunia)

- Haematuria (red flag for further investigation and referral to a urologist as this might indicate a diagnosis of underlying bladder cancer)

- Recurrent urinary tract infection

- Bowel history/symptoms, including constipation and incontinence

- Genitourinary history, previous urogynaecological or bowel surgeries, radiotherapy, pelvic trauma

- Obstetric and gynaecological history

- Parity and weight of baby/babies

- Delivery (eg vaginal, instrumentation)

- Neurological conditions (eg spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, strokes, dementia/cognitive impairment)

- Medications (including over-the-counter)

- Fluid intake (especially alcohol and caffeine intake) – some significant urinary symptoms can be purely a result of excessive fluid/caffeine intake. This can be diagnosed easily using a bladder diary

- Psychosocial

- Smoking, body mass index

- Use of continence aids

|

| Physical examination |

- Standing cough test (the patient stands with a full bladder and coughs, demonstrating leak or no leak, standing on a protective sheet)7

- Abdominal

- Pelvic or abdominal masses

- Palpable bladder

- Abdominal scars/stomas

- Genitourinary

- Atrophic vaginal changes

- Pelvic organ prolapse, the presence of enterocele or a cystocele

- Urethral changes (eg meatal stenosis, urethral prolapse, urethral caruncle)

- Genitourinary fistula

- Strength of pelvic floor contraction – this might be measured by an internal examination during which the patient bears down

- Spine and lower limb neurology

|

Investigations

Urology/specialty specific |

- Bladder diary – a chart given to the patient to fill out to outline symptoms8

- Urine – microscopy and culture to assess for infection, sterile pyuria, proteinuria, glycosuria. The presence of haematuria is a red-flag and warrants referral to a urologist for investigation of underlying bladder cancer

- Bloods – renal function

- Renal tract ultrasound – post void residual volume

- Voiding flow rate (the patient voids into a specialised toilet and the maximal and average flow rate in mL/s is assessed)

- Post void residual volumes

- Cystoscopy

- Urodynamic studies

|

SUI is considered complicated in women with neurological conditions affecting the urinary tract, and when there is concurrent pelvic pathology such as pelvic organ prolapse, previous pelvic surgery or radiotherapy. Complicated SUI or incontinence with unclear aetiology (perhaps when one is concerned about urge incontinence or SI-DO) warrants referral to a specialist.5

Conservative management

Many patients suffering from SUI can be effectively managed in the primary care setting with input from the general practitioner (GP), pelvic floor physiotherapists and nurse continence specialists. Proactive management of constipation, as well and encouraging reduced intake of alcohol and caffeine, are suggested.9 Both body mass index and waist circumference are positively associated with SUI,10 and weight reduction has been shown to lessen SUI symptoms, as well as improve postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing surgical intervention for SUI.11 The literature demonstrates that women with chronic respiratory conditions were twice as likely to develop urinary incontinence compared to the general population, so management of respiratory comorbidities is essential.12 Smoking cessation should also be recommended to relevant patients.9

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is highly effective in managing SUI and has a strong body of evidence (particularly in mild–moderate severity SUI cohorts).13–15 PFMT aims to strengthen the pelvic floor and sphincter complex and should be recommended as a first-line therapy to all patients with SUI13,14 (Table 4). In large systematic reviews, PFMT has been quoted to achieve continence in one in every three women (number needed to treat [NNT]=3, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2–5).15 Carefully fitted continence pessaries can aid in managing SUI,16 though use needs to be overseen by an experienced clinician and patients need to understand pessary care and risks (including vaginal erosion/ulceration, and in extreme cases, fistula). Continence pessaries are usually reserved for women who are either too frail to be considered for surgical intervention, or as a temporising measure for younger women wishing to complete childbearing before considering surgical intervention for their SUI. Continence aids (pads, liners, incontinence briefs) are important in protecting the skin and allowing patients to go about their activities of daily living.17

| Table 4. Conservative management strategies |

| Lifestyle |

- Smoking cessation

- Weight modification

- Management of constipation, management of respiratory comorbidities

- Reduction of alcohol and caffeine

|

| Pelvic floor muscle training |

Instruct the patient to sit or lie down in a relaxed position and then:

- squeeze the muscles around the anus (back passage) like you are trying to stop passing wind

Instruct the patient when they are on the toilet emptying their bladder to:

- try and stop the flow of urine and then start the stream again (only do this once a week)18

Referral to a pelvic floor physiotherapist |

| Aids |

- Pessaries

- Continence aids

|

Surgical treatment for SUI

Surgical procedures to manage SUI include urethral bulking agents, Burch colposuspension and urethral slings (synthetic and autologous fascial) (Table 5).

| Table 5. Complications and risks following different stress urinary incontinence (SUI) surgical options34 |

| |

Urethral bulking agent |

Mid-urethral slings |

Autologous (fascial) slings |

Burch Colposuspension |

| Failure |

10–20 |

10–20 |

10–20 |

30–70 |

| Recurrent SUI post procedure |

60–80 (most require second injection) |

10 |

10 |

20–40 |

| Worsening OAB/urge incontinence symptoms |

<5 |

10 |

10 |

5–10 |

| Injury to bladder requiring catheter for longer than usual |

Not applicable |

5–10 |

5–10 |

<5 |

| UTI |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Temporary voiding dysfunction/retention |

5–10 |

5–10 |

5–10 |

5–10 |

| Ongoing voiding dysfunction/retention |

<1 |

2–5 |

2–5 |

2–5 |

| Erosion/migration (of mesh, suture, bulking agent) |

<1 |

2–5 (probably underquoted in literature) |

– |

<1 |

| Severe bleeding, visceral injury |

– |

<2 |

<2 |

<2 |

| Chronic pain (including dyspareunia) |

– |

<5 (probably underquoted in literature) |

<5 |

<2 |

| Other |

|

|

|

<10 risk of future prolapse |

Data are presented as percentages.

OAB, overactive bladder; UTI, urinary tract infection. |

Urethral bulking

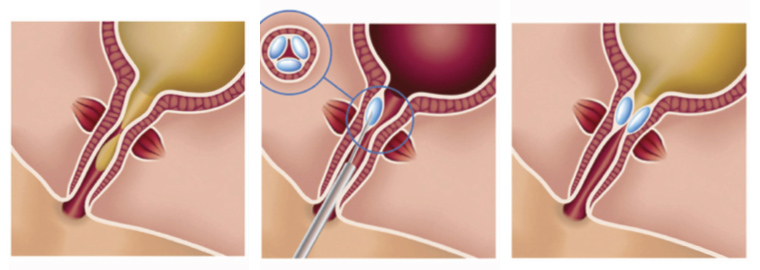

Urethral bulking agents are a minimally invasive, endoscopic technique to treat intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Bulking agents come in different compositions and are injected either transurethrally or periurethrally to expand the urethral tissue and improve urethral outlet resistance (Figure 1). The current, most commonly used bulking agent in Australia and New Zealand is Bulkamid® (Contura International A/S, Soeborg, Denmark), which has been shown to be an effective and safe product with short-term efficacy ranging between 30 and 90% according to systematic reviews.19 Although urethral bulking is less efficacious than other procedures, they are relatively non-invasive with a rapid post-procedure recovery (often performed as a day case) and remain effective for the treatment of women with mild SUI.

Figure 1. Peri-urethral injection of a bulking agent resulting in coaptation of the urethra.

Reproduced from Chapple C, Dmochowski R. Particulate versus non-particulate bulking agents in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Res Rep Urol 2019;11, with permission from Dove Medical Press Limited.

Slings

Mid-urethral slings (MUS) restore continence by supporting the middle portion of the urethra during periods of increased intra-abdominal pressure. This support reinforces the urethra’s closure mechanism, which can be compromised when the pubourethral ligaments lose their integrity.4 The MUS is the most widely studied and performed surgical technique for female SUI, and outcome data for over 2000 publications provide robust evidence to support the use of the MUS.20,21 A Cochrane review, assessing over 12,000 patients, demonstrated that the long-term (greater than five years) cure rate ranged from 43 to 92% (with no significant difference between transobturator and retropubic approaches).22

Despite controversy about the use of transvaginal mesh in prolapse surgery (not incontinence surgery), multiple international professional societies have position statements advocating the safety and effectiveness of the mesh MUS for SUI and advocate for its continued availability.23–26 The Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand published a position statement regarding the relative safety and effectiveness of the synthetic MUS for SUI with appropriate clinical governance, and it remains a surgical option in Australia today.24 Various safety precautions exist, including specific mesh credentialling and a mesh registry.21

Autologous pubovaginal fascial slings (PVS) are a mesh-free sling, placed transvaginally with the arms placed retropubically and secured over the suprapubic rectus fascia. Common graft sites include the rectus fascia and the fascia lata of the thigh. PVS were performed in increasing numbers following the concerns about the use of mesh for prolapse surgery27 and have comparable clinical outcomes to synthetic slings, without mesh-specific complications (Table 5).28 Systematic reviews quote success rates between 46.9 and 90%.22,29

Burch colposuspension

Burch colposuspension is a mesh-free treatment for primary SUI and involves placing sutures between the anterior vaginal wall (either side of the urethra) and Cooper’s ligaments, thereby elevating the urethra and providing a support mechanism against rises in intra-abdominal pressure. This can be performed via open surgery or laparoscopically/robotically. A 2017 Cochrane review involving a total of 5417 women found the overall one-year success rate to be 85–90%, and a five-year success rate of 70%.30 There is some evidence to suggest that women might not achieve as much continence in the medium term (one to five years) following a colposuspension when compared to a MUS;31 complications are listed in Table 5.

Artificial urinary sphincter

Although not usually considered a first-line surgical option,32 an artificial urinary sphincter can be utilised in women with recurrent, persistent or severe SUI (Figure 2). This is an implanted device consisting of a cuff around the bladder neck, a pump that is placed in the labia majora, and a pressure-regulating balloon/fluid reservoir placed in the prevesical space. The inflated cuff compresses the urethra at rest, and patients void by activating the pump in the labia, which deflates the cuff and allows passage of urine. Although female artificial urinary sphincters have good long-term outcomes, with studies quoting a 75% continence rate at 10 years, up to 46% of patients have been quoted to require revision surgery.33 Further high-level evidence studies are needed to help better define the role of the artificial urinary sphincter in the management of female patients with SUI.

Figure 2. Boston Scientific AMS 800 Artificial Urinary Sphincter (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA).

Reproduced from Carson CC. Artificial urinary sphincter: Current status and future directions. Asian J Androl 2020;22(2), with permission from Wolters Kluwer – Medknow.

The current local and international guidelines (American Urology Association, the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU), the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand, and the European Association of Urology) for surgical treatment of SUI recommend considering a range of surgical interventions based on individual patient factors, as we have described.23–26 The choice of procedure depends on factors such as the severity of SUI, the patient’s medical history, prior surgeries and patient preferences.

Conclusion

SUI is a common, yet often overlooked problem that has a significant impact on quality of life. Multiple treatment options exist, both non-invasive and surgical, and patients who do not respond to conservative management should be referred to a specialist, as many effective and safe surgical options are available. Despite controversy around the use of mesh, synthetic MUS remain a viable surgical option for female SUI.

Key points

- Stress urinary incontinence is a common medical issue and can be cured.

- Stress urinary incontinence must be differentiated from other types of incontinence – most importantly, stress-induced detrusor overactivity.

- Conservative treatment, including pelvic floor physiotherapy, should be recommended for all patients with uncomplicated SUI. Patients who do not respond to conservative treatment or are considered complex cases (previous incontinence/pelvic surgery, prolapse, neurological disease) should be referred to a specialist service.

- Many effective surgical options exist for patients with stress urinary incontinence, including minimally invasive urethral bulking agents and mesh-free surgeries (pubovaginal fascial sling, colposuspension).

- The Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand supports the ongoing use and availability of mid-urethral slings in Australia, where significant improvements in clinical governance have occurred since 2018. In Australia, enhanced clinical governance includes credentialing under guidelines of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, discussion of cases at multidisciplinary team meetings, informed consent and monitoring of patient outcomes using the national Australian Pelvic Floor Procedures Registry (APFPR).