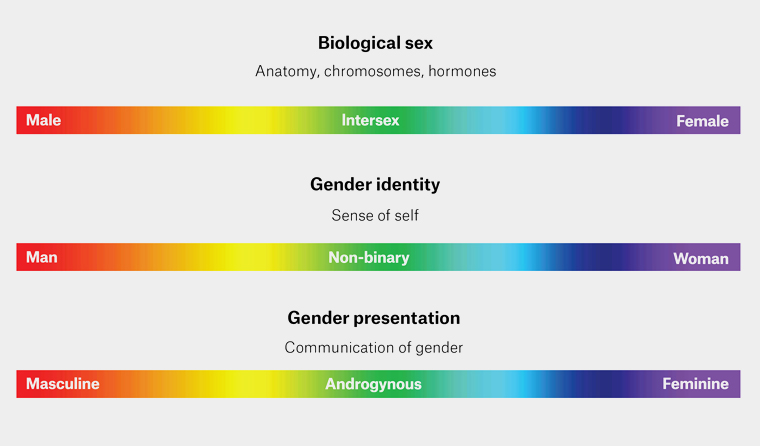

Gender affirmation surgery has an important role in the treatment of gender dysphoria.1 Gender dysphoria is defined as a marked incongruence between one’s experienced or expressed gender and gender assigned at birth.2 This state can be understood as a misalignment between ‘biological sex’ (typically understood as sexual organ and genetic characteristics) and ‘gender identity’. Gender dysphoria might occur at various developmental stages, but commonly escalates with development of secondary sexual characteristics (Figure 1).3

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the distinction between biological sex, gender identity and gender presentation displayed on a visible light spectrum. Used with permission from author, DH, from a personal figure library.

Multidisciplinary input can improve outcomes when treating patients with gender dysphoria.4 In this context, a multidisciplinary team commonly includes mental healthcare providers, sexual healthcare physicians, general practitioners (GPs), endocrinologists and surgeons.

These treatments are effective in managing gender dysphoria, and patients rarely regret gender affirmation therapy later in life.5,6 Various surgical options are available to transgender and non-binary individuals, which include facial reconstructive surgery, vocal surgery, chest or ‘top’ surgery, and genital or ‘bottom’ surgery (Table 1).7 This article will focus predominantly on available options for genital surgery.

| Table 1. Options for gender affirmation surgeries |

| Female-to-male surgeries |

Male-to-female surgeries |

| Facial masculinisation surgery |

Facial feminisation surgery |

| Vocal surgery (uncommon) |

Vocal surgery and chondrolaryngoplasty |

| Chest or ‘top’ surgery

|

Chest or ‘top’ surgery

|

Genital or ‘bottom’ surgery

- Scrotoplasty

- Testicular prosthesis

- Metoidioplasty (with or without urethral lengthening)

- Phalloplasty (with or with urethra)

- Flap type

- Radial artery forearm flap

- Anterolateral thigh flap

- Abdominal flap

- Myocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap

- Other flap

- Penile prosthesis

- Hysterectomy + bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- Vaginectomy

|

Genital or ‘bottom’ surgery

- Bilateral orchidectomy

- Scrotectomy

- Vaginoplasty

- Penile inversion

- Peritoneal pull through

- Penectomy

|

Aim

To provide GPs and surgeons with a brief summary on gender affirmation surgeries and guide for appropriate referral criteria.

Referral considerations

Gender affirmation surgery requires considered multidisciplinary input over a minimum of six months.8 An ideal candidate for referral to a reconstructive surgeon would:

- be psychologically stable; absence of psychosis, depression, alcoholism and intellectual disability8

- have a strong support network

- have a clear idea of their desired type of surgery

- have begun or planned hormonal transition. Current recommendation is a minimum of six months prior to ‘bottom’ surgery

- have undergone optimisation of modifiable surgical risk factors, including smoking cessation (recommended six months minimum), weight management (optimal body mass index [BMI] 21–29) and diabetes stabilisation.9 Elevated BMI is not an absolute contraindication to surgery, but would require a careful discussion of risks and benefits with the patient.

The two predominant methods used to assess patient appropriateness for surgery are the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines and the informed consent model.4,8,10,11

World Professional Association for Transgender Health

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health standards of care (SOC) are a detailed set of mental health-orientated criteria.8 Initially developed in 1979, these guidelines have evolved over eight iterations.8 Within its framework, mental health providers facilitate formal mental health evaluations and provide obligatory letters of readiness (Table 2). Initially, these guidelines highlighted the significance of psychiatric assessment to ascertain the persistence of gender dysphoria, often doubting the reliability of patient self-reporting. Historically, WPATH SOC mandated a period of psychotherapy and real-life experience living as one’s identified gender with referral letters from mental health professionals to validate eligibility for treatments, such as hormone therapy and surgery.8 Critics argue that these standards, although born from the principle of non-maleficence, have perpetuated a form of gatekeeping and paternalism that limits access to gender-affirming care.10,11 Despite the accumulating clinical experience and research supporting the safety and efficacy of gender-affirming treatments, some argue that the WPATH SOC continue to place a burden on transgender individuals to validate their identities to healthcare providers.10

| Table 2. Comparison of World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines and informed consent models of care for assessing suitability for gender affirmation surgery |

| |

Requirements |

Pros |

Cons |

| WPATH |

Mental health provider:

- Master’s-level degree

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD) competence

- Able to undertake capacity assessments

- Experience in treating patients with gender dysphoria

|

- Careful evaluation of gender dysphoria and mental health status

- Structured process for determining eligibility and readiness for treatment

- Historically rooted in established clinical practice

|

- Time-consuming and potentially stigmatising

- Requires involvement of mental health professionals, which might lead to delays in treatment

- Might be viewed as gatekeeping and paternalistic due to limiting access to care

|

| Informed consent |

- Informed decision making

- Capacity for consent

- Detailed discussion regarding risks, benefits and alternative treatments

|

- Reduces reliance on external evaluations and referral letters

- Fosters a strong clinician–patient relationship

- Aligns with evolving transgender healthcare practices and diverse identities

|

- Challenges related to insurance coverage criteria and access to care

- Potential concerns about lack of psychological evaluation for some patients

|

Informed consent model

The guiding principle underpinning the informed consent model is that patients experiencing gender dysphoria have capacity to make informed decisions and consent to medical or surgical management.10,12

In contrast to the WPATH SOC, the informed consent model does not require referral letters from mental health professionals and, instead, places trust in the treating clinician and patient to collaboratively determine the most suitable management course. This model acknowledges that patients, as experts in their own experiences, are best positioned to assess the benefits and risks of treatment. Given low rates of regret post intervention, some authors argue that the informed consent model should be used more commonly in contemporary practice.13

Perioperative considerations

The timing of gender affirmation surgeries is an important consideration in transgender healthcare. The timing is driven by where each individual is in their own journey of transition, the particular details of their dysphoria, their awareness and experience regarding sexual activity, as well as their overall preferences for managing their gender dysphoria.

In both the WPATH SOC and informed consent models of care, preparing for gender affirmation surgeries involves several key components.

Preoperative assessment is undertaken with evaluation of the patient’s physical health prior to surgery and focuses on optimisation of modifiable surgical risk factors including smoking cessation, BMI and diabetes.1

Other important considerations for the multidisciplinary team (Table 3) include:

- Hair removal: It is an important component in both phalloplasty and vaginoplasty surgeries to ensure minimal hair exists within a formed urethra or vagina, as well as cosmesis to align with desired genital appearance. This is commonly organised by gender surgeons.

- Fertility planning: Discussions around sperm or ovarian cryopreservation prior to surgery or hormone therapy should be undertaken by GPs or physicians organising these interventions.

- Family planning: Some patients might prefer to have a family prior to surgery, particularly surgery involving reproductive organs. Some patients might interrupt their hormone treatment to achieve a pregnancy.

- Preoperative hormonal levels should be assessed, particularly for individuals who have undergone hormone therapy as part of their gender affirmation. This is ideally organised via referral to a gender surgeon.

| Table 3. World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guideline criteria for referring patients to experienced gender-affirming surgical centres |

| Team member |

Requirements |

| Mental health team |

Mental health assessment and diagnosis of gender dysphoria by a qualified mental health professional |

| Psychological stability |

| Hormone prescriber (commonly endocrinologist or general practitioner) |

Hormone therapy for a minimum of 6 months |

| Surgeon |

Assessment of the patient’s understanding of the surgical process, risks and realistic expectations |

Surgical plans are tailored to each patient’s unique needs and preferences. Gender affirmation surgeries are highly individualised, and the specific procedures chosen should align with the patient’s gender identity and desired physical changes.11 Surgeons work closely with patients to create surgical plans that reflect their goals and might involve chest surgery, genital surgery, facial feminisation or masculinisation, among many other procedures.

Patient education is undertaken as a critical aspect of the surgical process. Patients should be well-informed before and after surgery regarding their expectations. Preoperative education includes information about the surgical procedure, potential risks, the recovery process and expected outcomes.9 Patients should have a clear understanding of the surgical process and its implications. Postoperative care instructions are important. Patients are educated on wound care, pain management and recognition of complications postoperatively.

Options for gender affirmation surgeries

Gender affirmation surgeries can be divided into female-to-male and male-to-female operations (Table 3).

Female-to-male surgeries

There are many female-to-male gender affirmation surgeries available (Table 1). Collaboratively choosing the appropriate operation requires detailed patient understanding of surgical options and limitations of outcomes.

Hysterectomy and vaginectomy

Managing gender dysphoria surgically often involves removal of female reproductive organs (Table 1). This can include removal of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, Fallopian tubes and vagina.9,14,15 Removal of the vagina is often paired with reconstructive surgery such as metoidioplasty or phalloplasty.9,14,16,17

Metoidioplasty

Metoidioplasty involves releasing the clitoral ligament and constructing a neophallus (new penis) from the enlarged clitoris.16 The procedure might include urethral lengthening, scrotoplasty or glansplasty.16 Importantly, the appearance of metoidioplasty resembles a pre-pubertal penis, rather than that of an adult male and it is rarely able to be utilised for penetrative intercourse. With urethral lengthening, people might be able to void in the standing position.

Benefits of metoidioplasty include alleviating gender dysphoria with a less invasive and less costly procedure, minimal scarring and the preservation of clitoral sensation.

Phalloplasty

Phalloplasty is another operative option for transgender men and non-binary individuals seeking gender affirmation surgeries. A variety of phalloplasty techniques are available, including radial artery forearm, thigh and abdominal flap phalloplasty.1,9,17–19

Radial artery forearm flap

This approach uses forearm tissue to create the neophallus. It offers excellent cosmesis and better sensation rates, but is accompanied by significant forearm scarring. A urethra is usually included.

Anterolateral thigh flap

A thigh flap has the benefit of being able to hide scarring under clothing. Sensation might be less than when a forearm flap is used, and some skin/body types might not be suitable for this option. Sometimes a urethra can be included.

Abdominal flap phalloplasty

This local flap is used for people with a suitable amount of abdominal tissue. Cosmesis and poor sensation are disadvantages of this approach. A urethra can be created, but requires a separate procedure that often involves a forearm free flap.

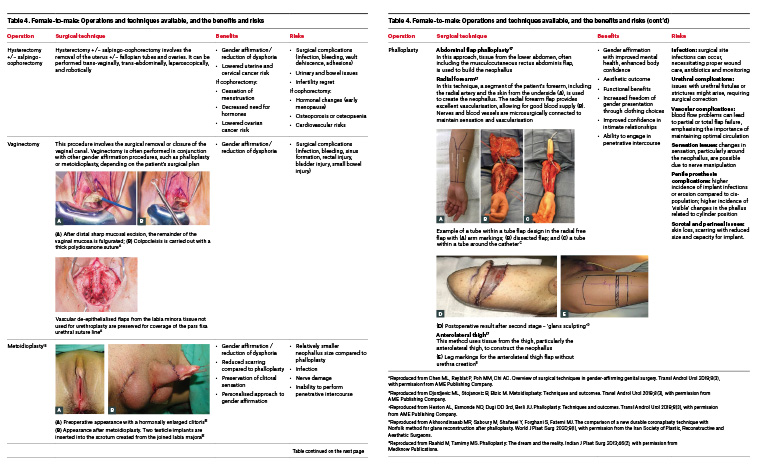

Complications and postoperative care

Postoperative care for phalloplasty and metoidioplasty patients involves regular follow-up appointments and wound care. Additional surgeries might be required to address complications. A variety of short- and long-term complications exist for phalloplasty (Table 4).

Table 4. Female-to-male: Operations and techniques available, and the benefits and risks. Click here to enlarge

Male-to-female surgeries

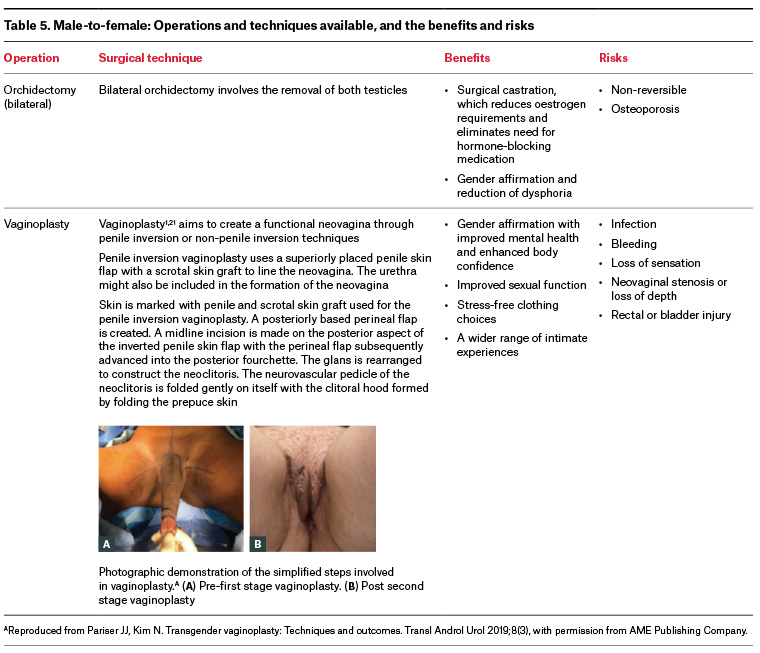

Gender affirmation surgery for trans-women generally involves orchidectomy, with or without scrotectomy, or some form of vaginoplasty.3,4

Orchidectomy involves the removal of both testicles and is suitable for those patients with significant testicular or scrotal dysphoria, as well as patients wishing to cease testosterone-blocking medications or to facilitate genital tucking.20

Vaginoplasty is a gender affirmation surgery designed for transgender women and non-binary individuals, aiming to create a neovagina. The surgical process includes two primary techniques: penile inversion or non-penile inversion. In the penile inversion approach, the penile skin is inverted to form the neovagina, whereas the non-penile inversion technique uses grafts or tissue from other areas of the body, such as the peritoneum, scrotum or sigmoid colon, to construct the neovagina. Vaginoplasty variants include zero depth, which focuses on external appearance without the vaginal canal, or full depth, which includes the creation of a functional vaginal canal (Table 5). Occasionally, a patient might prefer to have a penectomy, rather than a full reconstruction.

Table 5. Male-to-female: Operations and techniques available, and the benefits and risks. Click here to enlarge

Preoperative care involves thorough patient assessment, psychological evaluation and extensive discussions to clarify readiness and informed consent. Postoperative care includes pain management, dilation exercises and maintaining surgical site hygiene. Potential complications include infection, bleeding, rectal or bladder injury, loss of sensation and neovaginal stenosis or loss of depth. Vaginoplasty can be an important step in the gender affirmation process, aligning physical appearance with a patient’s gender identity. Pre- and postoperative care is essential to minimise complications and ensure successful outcomes.

Conclusion

Gender affirmation surgery is likely to have an increasingly important role in the management of gender dysphoria. It is important for primary care physicians and surgeons to understand available options for gender affirmation surgeries in Australia, as well as referral processes in order to optimise timely patient care.

Key points

- Gender affirmation surgeries are important for improving quality of life of transgender and non-binary individuals.

- General practitioners have an important role in transgender medicine, including capacity assessment, initiating hormone treatments and understanding optimal timing for referral to gender surgeons.

- Multidisciplinary, collaborative care between surgeons, general practitioners and other healthcare providers is vital for timely patient care.

- Continued research and education are necessary to provide optimal care to this often, under-serviced patient population.