Background

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men globally. A range of management options are available for prostate cancer, including surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, or surveillance. Conservative strategies include active surveillance and watchful waiting, which differ in their intent.

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men worldwide, and the management of this disease remains challenging.1 Prostate cancer accounts for the second most cancer-related deaths in men in Australia, where the lifetime risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer in Australia is four times the global risk.2 There are various treatment options available, which, dependent on patient and disease factors, include surgery and radiation for localised disease, and hormonal and chemotherapy for metastatic cancer.3,4 In addition, conservative strategies are used as a critical part of the urologist’s toolkit including active surveillance and watchful waiting. As survivorship populations increase, there will be an increasing role for primary care in shared care conservative management of prostate cancer.5,6

Aim

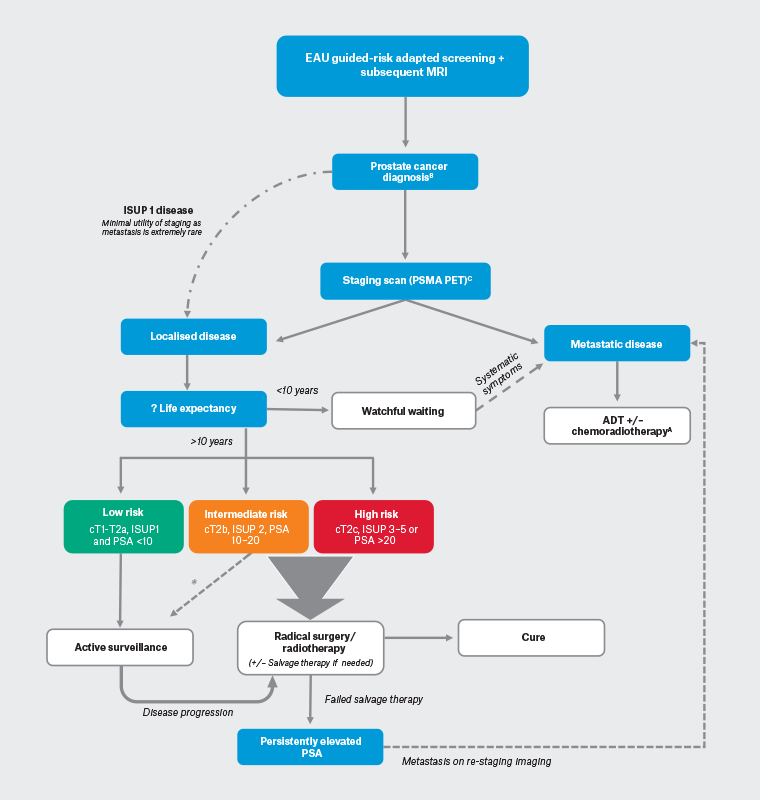

To provide a practical algorithm for better primary care understanding of conservative strategies in prostate cancer (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simplified overview of conservative strategies in the management of biopsy-diagnosed prostate cancer. Click here to enlarge

European Association of Urology (EAU) risk-adapted screening protocol that guides clinicians to appropriately order prostate-specific antigen (PSA; a protein produced by the prostate gland used as a biomarker for the detection and monitoring of prostate cancer), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and biopsy.19

AFor further details, see the European Society for Medical Oncology guideline for metastatic prostate cancer20 or the EAU/American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines.21,22

BNote that cancer diagnosis can come from tissue from other sources, such as a transurethral prostatic resection specimen.

CComputed tomography (CT) + bone scan if unavailable.

ADT, androgen deprivation therapy (a treatment strategy that reduces concentrations of male hormones, such as testosterone, to slow the growth of prostate cancer); cT1, Tumour Stage 1 (indicates the cancer is confined to the prostate gland and is not palpable or visible on imaging); cT2a, Tumour Stage 2a (indicates the cancer is still confined to the prostate gland but can be felt on a digital rectal examination; cT2b, Tumour Stage 2b (indicates the cancer has grown to involve more than half of one side of the prostate gland); cT2c, Tumour Stage 2c (indicates the cancer has grown to involve both sides of the prostate gland); ISUP, International Society of Urological Pathology (standardised criteria for grading prostate cancer based on microscopic examination of tumour samples); PSMA PET, prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography (a molecular imaging technique that uses a radioactive tracer to target prostate-specific membrane antigen, allowing for improved detection and staging of prostate cancer).

*ISUP 2 disease eligible for active surveillance if cores: <10% pattern 4, less than three positive; no intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (IDC)/cribriform growth.7

Prostate cancer surveillance strategies

Multiple conservative strategies exist in prostate cancer including ‘active surveillance’ and ‘watchful waiting’ (Table 1). These strategies are aimed at reducing overtreatment of indolent disease and maximising quality of life.

| Table 1. European Association of Urology definitions of active surveillance and watchful waiting7 |

| |

Active surveillance |

Watchful waiting |

| Treatment intent |

Curative |

Palliative |

| Follow-up |

Predefined schedule |

Patient specific |

| Assessment |

DRE, PSA, MRI at recruitment, rebiopsy |

Not predefined, dependant on symptom development |

| Life expectancy |

>10 years |

<10 years |

| Aim |

Minimise treatment toxicity without compromising survival |

Minimise treatment toxicity |

| Eligible patients |

Mostly low-risk patients |

Can apply to patients with all stages |

| DRE, digital rectal examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSA, prostate-specific antigen. |

Active surveillance

Active surveillance is a structured surveillance strategy with curative intent.7 It is now the recommended management strategy for men with low-risk disease (prostate-specific antigen [PSA] level of less than 10 ng/mL and ISUP 1 [Gleason score 3 + 3] and Clinical stage T1–T2a) who would be eligible for local treatment.8−10 Randomised trials have demonstrated that radical treatment of low-risk prostate cancer with surgery or radiotherapy does not confer a survival benefit compared to treatment with systemic treatment at the onset of progression/metastases and exposes patients to the morbidity of treatment.4 The results of long-term active surveillance cohorts have shown very high disease-specific survival in these men who have been managed conservatively.4 The clinical assumption underpinning active surveillance is that the estimated risk of disease progression to metastasis or cancer related death is low. Active surveillance is an ‘active’ process, in that the patient undergoes regular checks (three- to six- monthly), which might include measurement of PSA blood tests, digital rectal exams and repeat imaging with an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as interval prostate biopsies to assess for cancer progression.11 If there is evidence of disease progression based on these tests (tumour grade progression or growth on biopsy, PSA doubling time greater than three years or a shift in patient preference for definitive treatment), active treatment might be recommended because the risk of cancer progression is higher with intermediate- and high-risk disease and therefore a larger survival benefit can be gained by treatment.7,9,11 Patients with disease features that suggest either higher probability of sampling error or risk of progression (family history of lethal prostate cancer; BRACA1/2 germline mutation carries), or high levels of anxiety, might still be offered therapy up front even though they only possess low-grade disease on biopsy.

Active surveillance in favourable intermediate risk disease

Oncological outcomes for favourable intermediate risk prostate cancer are similar to low-risk disease (10-year metastasis-free survival [MFS] 95.5% vs 99.5%; 10-year prostate cancer-specific survival 94.4% vs 98.2%).3 As such, patients with low-volume ISUP 2 (defined as less than three positive systematic cores and less than 50% core involvement or another single element of intermediate-risk disease) can be considered for active surveillance. Stringent active surveillance is essential given the potential higher risk of progression, development of regional or distant metastases and death of this group compared with patients with low-risk disease. Current European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines state that if repeat non-MRI-based systematic biopsies reveal greater than three positive cores or 50% core of ISUP 2 disease, patients should be actively treated.7 However, in reality, surveillance cut-offs are often based on anxiety, there are inconsistent active surveillance treatment protocols and precocious shift to definitive treatment is common.12

Unfortunately, active surveillance is not currently routinely recommended in Australia in favourable intermediate disease (in contrast to the EAU and National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] guidelines).7,13,14 This is commonly driven by patient and physician anxiety regarding the ‘unpredictability of cancer progression’, rather than true clinical progression, leading to bias towards radical treatment.12 Future research to address anxiety by incorporating better prognostic biomarkers into clinical decision making could further risk stratify and dramatically alter the treatment landscape of early prostate cancer.

Watchful waiting

‘Watchful waiting’ is a conservative management strategy commonly used for patients who have an anticipated life expectancy of less than 10 years.

15 The ‘10-year’ life expectancy rule comes from randomised clinical trial evidence that demonstrates no significant deviation in the survival curves between active local treatment versus observation with delayed hormonal therapy until at least 10 years after intervention.

4 In this case, based on the current trial evidence, patients do not experience a survival gain from radical intervention for their primary tumour and are more likely to die from non-prostate cancer-related causes.

16 Thus, patients would be exposed to risk of post-operative/ post-radiation morbidity for minimal benefit. This approach is essentially palliative in intent, initiating treatment only when there are local symptoms, development of bony metastases and/or signs of rapid disease progression based on PSA kinetics. Patients are generally seen every 6–12 months for a clinical check and a periodic PSA measurement.

15 PSA measurement is useful in this scenario as rapid rises in PSA can indicate the development of metastases, and detection of bone metastases prior to them becoming symptomatic might improve quality of life and prevent fractures.

15 Data from longitudinal studies suggest the average time from a positive bone scan to the development of symptomatic metastases is nine months.

17 Hence a positive bone scan is the usual indication to commence ADT in this patient cohort.

Graduation from active surveillance to watchful waiting

Moore et al (2023) examined combined expert and patient views on active surveillance and transition to watchful waiting.

18 There was concordance that those who no longer require treatment for localised disease should transition to less intensive monitoring or watchful waiting. Views contrasted as to whether this should be based on age or life expectancy (age of 75 or 80 years or for a life expectancy of less than 10 years). There was uncertainty regarding the appropriateness of transitioning to watchful waiting for a life expectancy of less than five years.

Practical guide on general practitioner facilitation of active surveillance

Successful implementation of active surveillance requires effective communication, education, shared-care decision making and patient engagement. Centrally, patients choosing to pursue active surveillance need to be educated about the significance of consistent cancer monitoring to prevent missing the window of opportunity for curative treatment. Ensuring patient understanding that active surveillance is a safe and effective management option for prostate cancer is essential for proper treatment adherence and follow-up.

12 This can be done through counselling patients that in low-risk disease, active surveillance has been shown to reduce the risk of over-treatment and maintain quality of life by avoiding potential side effects such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

3,4

Conclusion

Active surveillance and watchful waiting are two alternative management strategies for prostate cancer that aim to avoid unnecessary treatment and harm. The distinction between the two approaches is treatment intent, which is informed by their respective clinically discrete patient populations. Where active surveillance involves close monitoring using clinical examination and investigations with an intent to cure, watchful waiting focuses on monitoring for symptom progression with an intent to minimise symptoms.

Key points

- Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men worldwide and a growing challenge for clinicians.

- Active surveillance and watchful waiting are distinct surveillance management strategies for prostate cancer that aim to avoid unnecessary treatment and harm.

- Active surveillance involves close monitoring of low-risk prostate cancer with curative intent, intervening with progression of disease, whereas watchful waiting involves treating symptoms arising from progressive systemic disease.

- Both active surveillance and watchful waiting are safe and effective management options for prostate cancer, and conservative observational measures have shown similar long-term outcomes as active treatment options.

- The decision to choose active surveillance or watchful waiting should be determined by life expectancy, disease biology and patient preference.