Type 2 diabetes (T2D) affects 15–19% of older Australians.1 Exercise and self-management are recommended for T2D due to their ability to improve health outcomes.2 Exercise interventions for T2D can reduce healthcare burden and are cost-effective (up to $50,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained or disability-adjusted life year averted).3 Group exercise and education interventions, including the combination of recommended aerobic training and progressive resistance training tailored to the individual, have been demonstrated to be capable of improving the health outcomes of older adults with T2D in community-based settings.4,5 Such interventions directly benefit glycaemic control, cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, cardiovascular risk, body composition, quality of life and physical function.6,7

Despite growth in the number of accredited exercise physiologists (AEP) able to deliver rebateable group services under Medicare in Australia, older adults with T2D remain less likely to attend or meet the physical activity guidelines than people without diabetes, with less than 0.01% of older adults with T2D accessing such services.8,9 There is no evidence evaluating AEP-delivered T2D Medicare group programs, which includes a subsidised initial assessment and eight group sessions annually. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to assess: (1) the feasibility and acceptability of an evidence-based, consumer-driven T2D group exercise and education intervention using AEP Medicare services for older adults with T2D (diabetes clinic); and (2) the effect of the diabetes clinic program on cardiometabolic health and fitness outcomes. It was hypothesised that the diabetes clinic would be feasible and acceptable among older adults with T2D.

Methods

This study used a single-group quasi-experimental design to investigate the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an AEP-delivered T2D group Medicare service for older adults. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) (HC200973), and the trial was registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry on 30 April 2021 (ACTRN12621000505808). All participants provided written informed consent. The study is reported in accordance with the CONSORT statement (feasibility trials)10 and the intervention reported in line with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist11 and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT).12

All assessments and group sessions were conducted at the UNSW Medicine and Health Lifestyle Clinic (UNSW Sydney, Australia) by a single AEP with over 12 years clinical experience. Completion of assessments and delivery of the intervention were in accordance with Medicare requirements for Item numbers 81110 and 81115, respectively, with each group having a minimum of two and maximum of 12 participants. All participants were bulk-billed under Medicare and were not charged any out-of-pocket fees for the exercise physiology services.

Permission was sought from Medicare Australia on 19 February 2021 for this trial to be completed; trial recruitment, enrolment and data collection occurred between May 2021 and October 2022. Participants were included if they were aged ≥65 years and had been diagnosed with T2D. Exclusion criteria included diabetes diagnosis other than T2D, abnormal cardiovascular response to exercise, unable to speak English and without a translator, or other health conditions that prevented exercise participation.

Initial assessment (90–120 minutes) included a health interview, physical assessment and questionnaires. Participants then received eight group sessions of 90 minutes once per week. Using baseline exercise assessment results, the AEP individualised and monitored exercise intensity and facilitated education (Table 1; Appendix 1). Where participants were unable to perform the listed exercises due to health or movement limitations, exercises were modified to a body weight or dumbbell alternative. The intervention did not provide a structured home exercise program, although it did include education on physical activity away from the program. A final assessment occurred in the week after the final group session.

| Table 1. Diabetes clinic exercise session programming principles |

| Principle |

Aerobic exercise |

Resistance exercise |

| Frequency |

|

|

| Intensity |

- Light to vigorous (light 40–55% HRmax/RPE 8–10; moderate 55–70% HRmax/RPE 11–13; vigorous 70–90% HRmax/RPE 14–16)

|

- Light to vigorous (light 30–49% 1RM/RPE 9–11; moderate 50–69% 1RM/RPE 12–13; vigorous 70–84% 1RM/RPE 14–17)

|

| Time |

|

- 20–30 min

- Sets: 3

- Repetitions: 8–12 (aim for 10)

|

| Type |

- Cycling, rowing, stepping

|

- Pin-loaded weight plate machines, body weight, dumbbell exercises

|

| Pattern |

- One continuous bout (eg 15–20 min on one type) or two bouts (1×10 min cycling and 1×10 min rowing)

|

- 2-s concentric, 3-s eccentric with 1-min rest between sets

|

| Progression |

- Commence first sessions Week 1 at low–moderate intensity depending on training experience and gradually progress towards moderate–vigorous intensity as tolerated by the individual when HR and RPE consistently (two consecutive sessions) at lower end of intensity range

- Progression implemented by increased speed or workload

|

- Commence first sessions Week 1 at low–moderate intensity depending on training experience and gradually progress towards moderate–vigorous intensity as tolerated by the individual when RPE consistently (two consecutive sessions) at lower end of intensity range and technique/form stable

- Progression implemented by increased load

|

| 1RM, one-repetition maximum; HR, heart rate; HRmax, heart rate maximum; RPE, rate of perceived exertion. |

The primary outcomes were feasibility and acceptability. Feasibility was examined in terms of group session attendance, quantified as total sessions attended out of a maximum possible of eight and reported as a percentage. The criterion for feasibility was attendance at five or more of the eight (62.5%) group sessions, in line with the current AEP Medicare attendance rates of 5.27 of eight group sessions.8,13 Feasibility was further quantified as session compliance with criteria for success requiring performance of at least 10 minutes of aerobic training and five progressive resistance training exercises per session. Participant attendance, exercise programming and adverse events were recorded each session on pre-prepared hard copy sheets by the AEP during the sessions. Participants’ perspectives on the acceptability of the interventions were based on the final diabetes clinic assessment participant evaluation and feedback questionnaires. Acceptability was analysed through individual scores from five questions using a five-point Likert scale encompassing participants’ self-reported agreement with enjoyment, exercise appropriateness, improved understanding of diabetes self-management, improved health and willingness to attend again (Appendix 2). Participants also completed the global perceived effect scale.

Secondary outcomes were changes in health from the initial to final assessment and included resting heart rate, resting blood pressure, body weight, height, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), six-minute walk test (6MWT) distance, short physical performance battery including times to perform the five times sit-to-stand (5×STS) test, side-by-side stance, semi-tandem stance, full tandem stance and eight-foot walk, duration of single leg balance, handgrip strength, whole body strength (composite outcome calculated by the addition of all upper body and lower body one-repetition maximum [1RM] results: supported row, leg press, chest press, leg extension, lat pulldown and leg curl) and glycaemic and lipid profiles. These outcome measures were identified a priori due to their clinical meaningfulness across multiple aspects of health and fitness with protocols for participant assessment presented in Appendix 3.

There were limited data to support a precise a priori sample size calculation to power this feasibility study. However, 30 participants is considered an acceptable number for pilot feasibility studies.14 Medicare data demonstrate that the 65- to 75-years age group was largest group accessing group T2D AEP services in 2019, with close to 3000 and 4000 group services delivered in New South Wales to men and women, respectively,8 indicating a single-site sample of 40 would be realistic to achieve over a 12-month period given the resource constraints of the intervention. Assuming at least a 10% drop out for exercise interventions,15,16 and based on Kirwan et al,17 who reported a sample size of 43 for a community-led diabetes exercise and education program, we considered a sample size of 40 would be sufficient to meet our primary aim of determining the feasibility and acceptability of the diabetes clinic.

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS (version 28.0.1.0). Demographic, health condition, attendance and acceptability data are reported as percentages and as the mean and standard deviation (SD) unless stated otherwise. The preliminary efficacy of the diabetes clinic in terms of secondary outcomes was analysed using linear mixed models on the pre- and post-test data, with pre–post change entered in the fixed-effects model and participant ID entered in the random-effects model, with the linearity assumption visually inspected.18 Statistical significance was accepted at P≤0.05. The clinical significance of changes in applicable outcome measures is also presented.

Results

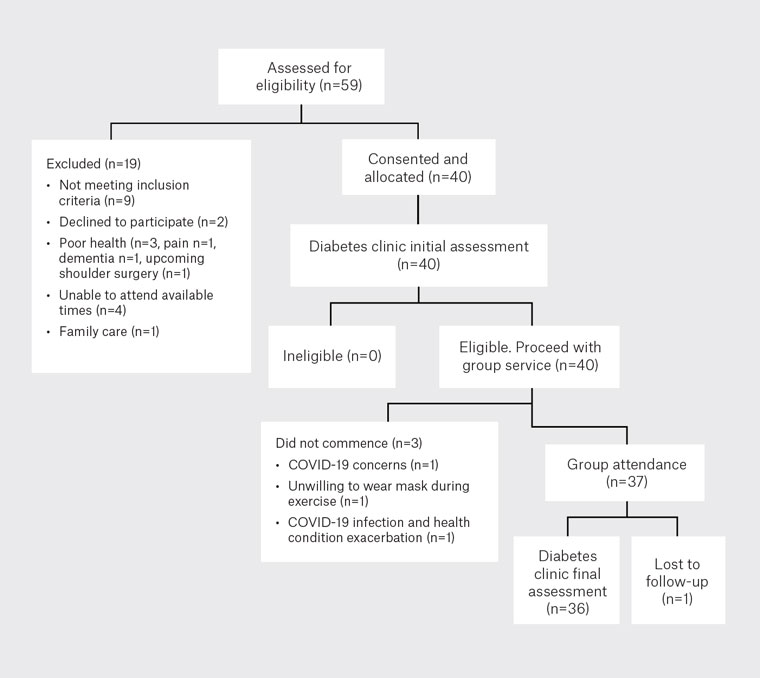

Overall, 59 people were screened for eligibility, with 80% (n=40; mean age 71.8±4.5 years; 18 [45%] female) of those eligible participating in the diabetes clinic initial assessment (Figure 1). Of these 40 participants, 93% (n=37) participated in the group sessions (87% overall session attendance) and 90% (n=36) completed the final assessment. Table 2 shows the results of participants’ baseline assessment. Participants’ years since diagnosis with T2D ranged from one to 40 years (mean 13.6±1.6 years). Because pathology was not collected as part of the trial protocol but rather requested from the participants’ latest results with their medical doctor, not all participants had glycaemic (only 80% available) and lipid (72.5% available) profiles available for analysis. This adds an interesting aspect to the study in that 35% of participants did not have regular three-monthly glycated haemoglobin measurement as per Australian guidelines for patients with T2D undergoing therapeutic changes such as participating in the intervention.2 Participants’ demographic and lifestyle behaviour characteristics are presented in Appendix 4.

Figure 1. Participant flow diagram for the diabetes clinic program.

| Table 2. Diabetes clinic participant baseline outcome measures |

| Characteristic |

Total |

Men |

Women |

| |

n |

Mean±SD |

n |

Mean±SD |

n |

Mean±SD |

| Age (years) |

40 |

71.8±4.5 |

22 |

72.0±4.6 |

18 |

71.6±4.6 |

| Years since T2D diagnosis |

40 |

13.6±10.3 |

22 |

15.0±10.8 |

18 |

11.8±9.6 |

| Vital signs and body composition |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) |

40 |

72±10 |

22 |

71±10 |

18 |

73±11 |

| SBP (mmHg) |

| Right |

39 |

141±19 |

22 |

143±17 |

17 |

140±22 |

| Left |

40 |

140±17 |

22 |

140±14 |

18 |

141±21 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

| Right |

39 |

78±9 |

22 |

80±8 |

17 |

76±10 |

| Left |

40 |

78±10 |

22 |

80±10 |

18 |

77±10 |

| Weight (kg) |

40 |

82.4±16.2 |

22 |

89.0±16.4 |

18 |

74.3±11.9 |

| Height (m) |

40 |

1.66±0.08 |

22 |

1.72±0.05 |

18 |

1.60±0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

40 |

29.7±4.6 |

22 |

30.2±5.2 |

18 |

29.1±3.9 |

| WC (cm) |

40 |

106.3±14.0 |

22 |

111.1±15.1 |

18 |

100.5±10.2 |

| Functional capacity and balance |

| 6MWT distance (m) |

39 |

455±89 |

22 |

457±88 |

17 |

452±92 |

| 5×STS (s) |

40 |

9.1±2.2 |

22 |

9.2±2.0 |

18 |

9.1±2.4 |

| Side-by-side stance (s) |

40 |

10±0 |

22 |

10±0 |

18 |

10±0 |

| Semi-tandem stance (s) |

40 |

10±0 |

22 |

10±0 |

18 |

10±0 |

| Full tandem stance (s) |

40 |

9.5±1.9 |

22 |

3.3±2.1 |

18 |

9.6±1.6 |

| 8-foot walk (s) |

40 |

1.9±0.4 |

22 |

1.8±0.3 |

18 |

2.0±0.4 |

| SPPB summary ordinal scale |

40 |

12±0.7 |

22 |

12±0.6 |

18 |

12±0.8 |

| SLB eyes open (s) |

| Right |

39 |

33.8±52.6 |

21 |

31.8±36.7 |

18 |

36.0±67.6 |

| Left |

39 |

30.2±50.1 |

22 |

26.1±28.3 |

17 |

35.6±69.7 |

| SLB eyes closed (s) |

| Right |

36 |

2.9±2.0 |

19 |

2.5±1.4 |

17 |

3.3±2.5 |

| Left |

36 |

2.7±1.8 |

20 |

2.4±1.3 |

16 |

3.3±2.3 |

| Muscular strength |

| Handgrip (kg) |

| Right |

40 |

28.3±8.2 |

22 |

32.9±6.9 |

18 |

22.7±6.0 |

| Left |

40 |

27.5±7.8 |

22 |

32.4±5.7 |

18 |

21.5±5.3 |

| Total |

40 |

55.8±15.6 |

22 |

65.3±12.1 |

18 |

44.2±10.8 |

| 1RM supported row (kg) |

40 |

43.1±14.0 |

22 |

52.6±10.4 |

18 |

31.4±7.2 |

| 1RM chest press (kg) |

39 |

31.9±11.0 |

21 |

39.5±8.8 |

18 |

22.9±4.8 |

| 1RM lat pulldown (kg) |

31 |

42.1±10.7 |

18 |

48.4±9.3 |

13 |

33.5±5.0 |

| 1RM leg press (kg) |

38 |

102.0±37.0 |

21 |

123.6±28.8 |

17 |

75.3±27.5 |

| 1RM leg extension (kg) |

39 |

34.8±13.2 |

22 |

39.9±13.7 |

17 |

28.2±9.3 |

| 1RM leg curl (kg) |

39 |

17.8±9.5 |

22 |

22.3±7.2 |

17 |

12.1±9.1 |

| Upper limb strength (kg) |

40 |

106.8±40.3 |

22 |

129.9±35.9 |

18 |

78.5±24.5 |

| Lower limb strength (kg) |

39 |

151.9±56.6 |

22 |

179.9±52.2 |

17 |

115.6±39.6 |

| Whole body strength (kg) |

40 |

255.0±93.7 |

22 |

310.0±79.4 |

18 |

187.6±60.1 |

| Pathology |

| BGL (mmol/L) |

28 |

6.3±1.0 |

16 |

6.3±1.2 |

12 |

6.3±0.8 |

| HbA1c (%) |

32 |

6.6±0.7 |

17 |

6.7±0.7 |

15 |

6.4±0.7 |

| TC (mmol/L) |

29 |

3.9±0.7 |

15 |

3.7±0.8 |

14 |

4.0±0.6 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) |

27 |

1.9±0.6 |

14 |

1.9±0.7 |

13 |

1.9±0.6 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) |

27 |

1.4±0.4 |

14 |

1.3±0.4 |

13 |

1.5±0.1 |

| TG (mmol/L) |

28 |

1.2±0.6 |

15 |

1.2±0.5 |

13 |

1.3±0.7 |

| Total PA time (min) |

40 |

308±197 |

22 |

316±210 |

18 |

299±185 |

| 1RM, one-repetition maximum; 5×STS, five times sit to stand; 6MWT, 6-min walk test; BGL, blood glucose levels; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PA, physical activity; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; SLB, single leg balance; SPPB, short physical performance battery; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference. |

The criterion for successful feasibility was achieved with participants attending 7.0±2.2 of the maximum eight sessions, equating to 87% overall attendance, with no significant difference (P=0.8) in attendance between men (6.9±1.8; 86%) and women (7.1±2.6; 88%). A group size of five participants was selected due to clinic space availability, with attendance ranging between two and six participants per session. Overall, participants were compliant with the aerobic training (86%), progressive resistance training (86%) and educational components (87%) of the sessions. Reasons for non-compliance with aerobic training and progressive resistance training included session non-attendance (41/320 sessions), late attendance (aerobic training only, 3/320 sessions) and exercises requiring modification due to health/movement limitations (1/320 sessions of aerobic training; 2/320 sessions of progressive resistance training).

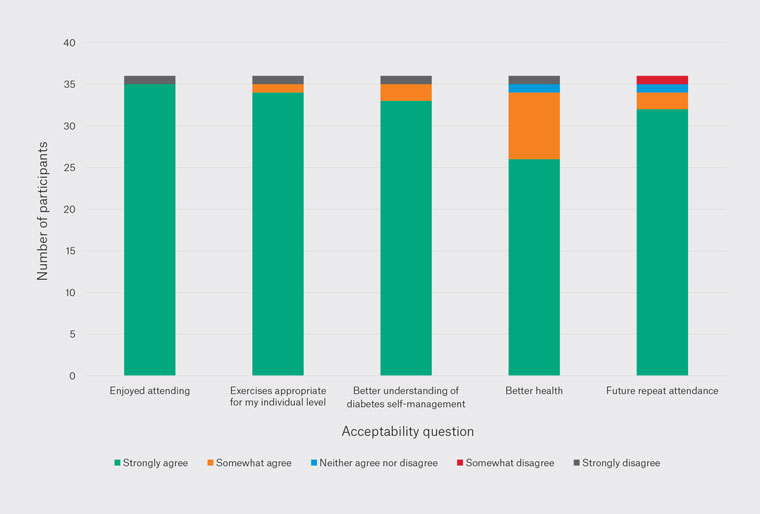

Participants reported high levels of acceptability (Figure 2). Of the 36 participants (90%; 15 females) who completed the final assessment and feedback questionnaires, 97% strongly agreed that they enjoyed attending the diabetes clinic. Overall, most participants somewhat or strongly agreed the exercises were appropriate to their individual level (97%), felt they had a better understanding of how to manage their diabetes (97%), felt their health was better (94%) and indicated they would attend the diabetes clinic again in the future (94%). When participants were asked how they would describe the change (if any) in activity limitations, symptoms, emotions and overall quality of life related to their T2D, most indicated an improvement (Appendix 5). When asked to rate the degree of change on a 0–10 scale (with 0 being much better, 5 no change and 10 much worse), the mean score was 3±2 (range 0–8).

Changes in participants’ health outcome measures are summarised in Table 3. There were statistically significant and clinically relevant reductions in systolic blood pressure on the right side (mean difference [MD] –7 mmHg; 95% confidence interval [CI]: –12, –2 mmHg; P=0.007) and left side (MD –6 mmHg; 95% CI: –11, –1 mmHg; P=0.013) and diastolic blood pressure on the left side (MD –3 mmHg; 95% CI: –5.0, 0 mmHg; P=0.021), but not on the right side (MD –1.8 mmHg; 95% CI: –4, 0.0 mmHg; P=0.84). There were significant improvements in weight (MD –0.7 kg; 95% CI: –1.3, –0.0 kg; P=0.039), WC (MD –1.3 cm; 95% CI: –2.2, –0.4 cm; P=0.006), 6MWT distance (MD 22.8 m; 95% CI: 9.1, 36.5 m; P=0.002), 5×STS (MD –0.8 s; 95% CI: –1.2, –0.5 s; P<0.001) and short physical performance battery ordinal scale (MD 0.3; 95% CI: 0.1, 0.5; P=0.009); however, none of these changes was clinically significant.

Significant improvements in all upper and lower limb 1RM assessments were achieved, except for leg curl; whole body strength improved by 15.6% (MD 32.2 kg; 95% CI: 22.3, 42.1 kg; P<0.001). No adverse events were reported during the exercise testing or training sessions. One participant’s resting blood pressure was elevated prior to commencing one of the exercise sessions. They did not participate in the exercise component of that session and continued the following week after cardiologist review of their hypertensive medication.

Figure 2. Participant acceptability of the diabetes clinic.

| Table 3. Change in pre–post assessment outcome measures after diabetes clinic intervention |

| Outcome measure |

Mean difference |

95% CI |

P-value |

Clinical significance |

| Vital signs and body composition |

| RHR (bpm) |

0 |

–2, 3 |

0.711 |

N |

| SBP (mmHg) |

|

|

|

|

| Right |

–7 |

–12, –2 |

0.007 |

Y |

| Left |

–6 |

–11, –1 |

0.013 |

Y |

| DBP (mmHg) |

|

|

|

|

| Right |

–2 |

–7, 0 |

0.084 |

Y |

| Left |

–3 |

–5, –0.0 |

0.021 |

Y |

| Weight (kg) |

–0.7 |

–1.3, –0.0 |

0.039 |

N |

| Height (m) |

–0.00 |

–0.00 – 0.00 |

0.472 |

N |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

–0.2 |

–0.4, 0.0 |

0.093 |

N |

| WC (cm) |

–1.3 |

–2.2, –0.4 |

0.006 |

N |

| Functional capacity and balance |

| 6MWT (m) |

22.8 |

9.1, 36.5 |

0.002 |

N |

| 5×STS (s) |

–0.8 |

–1.2, –0.5 |

<0.001 |

N |

| Side-by-side stance (s) |

0.0 |

0, 0 |

– |

– |

| Semi-tandem stance (s) |

0.0 |

0, 0 |

– |

– |

| Full tandem stance (s) |

0.5 |

–0.1, 1.2 |

0.088 |

N |

| 8-foot walk (s) |

–0.1 |

–0.2, 0.1 |

0.375 |

N |

| SPPB summary ordinal scale |

0.3 |

0.1, 0.5 |

0.009 |

N |

| SLB eyes open (s) |

|

|

|

|

| Right |

2.0 |

–3.7, 7.6 |

0.486 |

N |

| Left |

1.9 |

–6.1, 10 |

0.627 |

N |

| SLB eyes closed (s) |

|

|

|

|

| Right |

0.3 |

–0.5, 1.1 |

0.477 |

N |

| Left |

0.2 |

–0.5, 0.8 |

0.611 |

N |

| Muscular strength |

| Handgrip (kg) |

|

|

|

|

| Right |

0.6 |

0.4, 1.6 |

0.232 |

N |

| Left |

0.7 |

–0.2, 1.6 |

0.109 |

N |

| Total |

1.3 |

–0.4, 3.1 |

0.129 |

N |

| 1RM supported row (kg) |

3.5 |

2.0, 4.9 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| 1RM chest press (kg) |

3.4 |

2.1, 4.6 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| 1RM lat pulldown (kg) |

2.88 |

1.0, 4.7 |

0.004 |

N/A |

| 1RM leg press (kg) |

13.1 |

8.0, 18.1 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| 1RM leg extension (kg) |

5.8 |

3.4, 8.3 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| 1RM leg curl (kg) |

1.4 |

–0.1, 2.8 |

0.065 |

N/A |

| Upper limb strength (kg) |

8.9 |

6.1, 11.7 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| Lower limb strength (kg) |

19.9 |

13.7, 26.1 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| Whole body strength (kg) |

32.2 |

22.3, 42.1 |

<0.001 |

N/A |

| Pathology |

| BGL (mmol/L) |

0.1 |

–0.4, 0.5 |

0.783 |

N |

| HbA1c (%) |

–0.1 |

–0.4, 0.1 |

0.224 |

N |

| TC (mmol/L) |

–0.0 |

–0.2, 0.2 |

0.899 |

N |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) |

–0.1 |

–0.4, 0.1 |

–1.3 |

N |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) |

0.1 |

–0.0, 0.1 |

0.075 |

N |

| TG (mmol/L) |

0.0 |

–0.1, 0.2 |

0.595 |

N |

| 1RM, one-repetition maximum; 5×STS, five times sit to stand; 6MWT, 6-min walk test; BGL, blood glucose levels; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SLB, single leg balance; SPPB, short physical performance battery; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference. |

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of an AEP-led group T2D program for older adults under the Australian Medicare group T2D item. The intervention was feasible and acceptable, with an 87% attendance rate and 97% of participants strongly agreeing the intervention was enjoyable. Participation was also associated with clinically improved blood pressure, body weight, WC, functional exercise capacity, 5×STS, balance and muscular strength.

Community-delivered group services offer a means to provide exercise and education in a cost-effective manner through Medicare. Despite its introduction to the Australian Medicare system over a decade ago, the diabetes group service remains underutilised, with less than 1% of older Australians accessing the individual AEP assessment to enter group T2D services under Medicare in 2022.8 With over 678,300 older Australians estimated to have diabetes, evaluation of these services is valuable in understanding the nuances of older adults’ engagement in healthcare and providing insights as to why such services are not being accessed.1 Our diabetes clinic included a final assessment that is currently not included in the Medicare group service subsidised sessions. In line with the 2018 Allied Health Professions Australia recommendations, the call for the addition of a final assessment is strongly supported.13 Having information on feasibility and acceptability, as well as potential intervention effects on health outcomes, can contribute to a more thorough program evaluation, which can better inform program design and public health policy to ultimately enhance healthcare for older adults with T2D.

Participation in the diabetes clinic was not associated with a significant improvement in glycaemic control through reductions in either glycated haemoglobin or fasting blood glucose levels, potentially due to the short duration and session frequency of the intervention and lack of dietary prescription,19 as well as pathology results not being collected as part of the trial but rather as part of routine care with the participants’ general practitioner or endocrinologist. Future interventions should look to include the routine collection of bloods and longer-term (greater than six months) follow-up to further understand the effects of the intervention on cardiometabolic health.

In Australia, referrals to AEPs continue to be underutilised, especially for older adults and those from non-English-speaking backgrounds.20 Despite online programs being shown to have similar effectiveness to in-person programs for older adults with T2D,21 the existing Medicare scheme does not accommodate telehealth for group services, which might pose accessibility challenges for many Australians. Lifestyle interventions have been shown to be cost-saving in Australia, with exercise interventions capable of reducing total healthcare costs by up to 50% per day in the intervention group compared with controls.3 The T2D consumer benefits–cost ratio sees an expected health return of $8.50 for every $1 spent on AEP interventions.22 It is important to note that while participants in other studies experienced an increase in costs for diabetes care associated with engagement in T2D programs, other health service costs decreased or remained unchanged,23 highlighting the potential value of such services. Therefore, further evaluating the delivery of group services in different contexts, including rural and remote areas, can accommodate the wide spectrum of individual needs.

The addition of education to these group sessions, as delivered in the ‘Beat It’ intervention facilitated by Diabetes NSW and ACT (https://digital.diabetesaustralia.com.au/beat-it), demonstrates how services including a holistic range of lifestyle intervention options have the potential to improve on fitness measures and quality of life.5 Such programs often include longer-duration and more session designs, and on occasion out-of-pocket expense, compared with the eight sessions available under Medicare. Because the exercise guidelines for people with T2D call for exercise to be performed most days of the week, with these behaviours ideally continuing for more than eight weeks,6 it is understandable that developed T2D programs adopt a higher session frequency or encourage a structured home-based component in an attempt to have a greater effect on health outcomes. Because AEPs, accredited practising dieticians and diabetes educators are eligible allied health professional providers of the group T2D services under Medicare, future interventions should consider multidisciplinary delivery. Investigating feasibility from a clinician and business perspective would also be advised to improve the understanding as to why this valuable Medicare service is underutilised across Australia and could encompass general practitioner referral.

Conclusion

The diabetes clinic, an AEP-led group T2D service delivered under Medicare, is both feasible and acceptable to older Australians who attend, while also improving participants’ cardiometabolic health and fitness. Such programs have the potential to improve diabetes management in a diverse range of older adults through increased participation in healthy lifestyle behaviours, including exercise. Healthcare policy should focus on improving general practitioner and allied health professional awareness of the efficacy of such programs to enhance referrals. Additional Medicare-subsidised group sessions have the potential for greater engagement with physical activity guidelines, health outcome improvement and reduced health expenditure.