Background

Medical certificates communicate the needs and conditions of a person to (often) non-medical entities or other stakeholders. Medical certificates can have a profound effect on patients’ access to social and financial support, and therefore wellbeing. However, general practitioners (GPs) are not formally trained in effective completion of medical certificates, leaving opportunity for workforce development.

Medical certificates are produced in general practice for a variety of reasons. Their purpose is usually to inform a receiver of an individual’s medical condition(s) and their (in)ability to work or participate in occupational duties. The more familiar type for patients is a concise ‘sick note’, which certifies a temporary non-serious illness that has caused a short-term incapacity to work. However, there are more complex medical certificates produced by general practitioners (GPs) to communicate the circumstances of an individual to a third party. They range from certifying letters to specially designed forms, such as a Work Capacity Certificate (workers’ compensation form [132m])1 or a Centrelink Medical Certificate form (SU415).2 In this article, we focus on the latter type. The receiver of these certificates is often a non-medical person, such as a social security officer, employer or insurance agent. Writing a medical certificate is widely acknowledged as a challenging task, especially for international medical graduates (IMGs) with limited knowledge and experience of the health and social systems where they are practising.3,4 Our first author (PD) vividly recalls her first day working as a GP in Australia; needing to produce a worker’s compensation certificate for an injured worker while feeling anxious and frustrated from lack of experience and training in writing medical certificates and also the need to communicate clearly and professionally in a second language.

This article aims to review the scant literature available on the topic of writing medical certificates and, in doing so, discuss some of the challenges GPs face in the process by putting two possible responses in the spotlight. We have divided the challenges of GPs producing medical certificates into two categories: (i) the double roles GPs play as assessor and advocate; and (ii) the importance of words used for the ‘success’ of the case. Subsequently, we will address potential measures aimed at improving the current situation.

GPs in double roles: Assessor and advocate

Completing a medical certificate can be perceived by GPs as a complicated and bothersome task.3,4 This is because GPs often have a close relationship with their patient and might find it difficult to advocate for positive outcomes while also fulfilling the requirements of an objective assessor in certifying sickness/disability. In the nationwide cross-sectional study by Engblom et al of primary care physicians in Sweden, it was reported that sickness certification was challenging for half of the respondents.3 Many GPs report that the certification process can also be a source of conflict and tension in the therapeutic relationship, frequently resulting in dissatisfaction about the process.4,5

Words matter: Effective completion of certificates

Effective completion of a medical certificate begins with accessing the right form and selecting the appropriate option, which can be a challenge considering the wide variety of forms available for different stakeholders. Then comes the important job of completing the free-text sections (this can get more streamlined by the potential introduction and adoption of online certificates). Accessing social benefits or insurance claims heavily relies on the language used to communicate the patient’s condition. This means that words that are used to complete a medical certificate can have a significant effect on the action taken by stakeholders.

Enhancing the coherence of the words in the medical certificate has been suggested as a way to improve the pace of recovery and return to work for the patient.6 The approach to communication, whether it is emotionally persuasive or strictly factual, can also impact the success of the claim.7 However, certificates worded based on emotions that appeal to the reader’s goodwill are often overlooked by the authorities.7 Similarly, how the certificate is worded can have a serious impact on a worker’s mental health, especially considering the associated stigma and negative stereotypes often directed at claimants, portraying them as opportunistic in pursuing financial support.8 This stigma can have a negative effect on a range of issues, including the desire to access worker’s compensation by an injured worker, recovery and early return to work.

Navigating forward: The call for greater guidance and support

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, work-related injuries and illnesses cost $28.6 billion annually.9 The majority of the injured workers are initially assessed by a GP to determine their capacity to return to work. More than 70% are deemed to be unfit-for-work on their initial certificate.10 Similarly, GPs are less likely to write a fit-for-work certificate for mental health claims.11 This trend is noteworthy considering the potential benefits of early return to work, which have been linked to increased employment participation and reduced societal costs.12 The discrepancy in fitness assessments by GPs might be improved by further training.

Although several countries including Australia introduce some courses in communications for medical practitioners and assess a doctor’s communication skills via objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs),13 little formal training exists for writing medical certificates. One positive initiative was the Australian Family Physician Journal that published a ‘Paperwork’ series in 2011 to provide guidance for GPs on how to best complete various medical certificates. Some of these articles focused on describing the legal aspect of sickness certification14,15 and the legality of producing medical reports,16 whereas others provided guides on filling out commonly used forms such as those for Centrelink,17 Worker’s compensation,18 Department of Veterans’ Affairs,19 a death certificate,20 motor accident insurance,21 pre-employment medical22 and fitness to drive forms.23 Although these guides are very helpful in understanding the legal issues involved with producing a report, such as the structure and the relative code of conduct, they do not underscore the importance of the language used to achieve the desired outcome.

Another example is Sweden, which introduced nationwide guidelines for sickness certification in 2007.24 Most Swedish GPs found the guidelines beneficial in ensuring accurate sickness certification and more effective communication with stakeholders.25 However, almost half of those using the guidelines found it challenging to adhere to, highlighting the need for training to enhance competence. Similarly in Australia, when WorkSafe Victoria (WSV) and the Transport Accident Commission (TAC), Victoria’s two statutory injury compensation authorities, redesigned their sickness certificates in 2013 to focus more on capacity rather than sickness, it was reported by four stakeholder groups (GPs, injured workers, compensation agents and employers) that more training for GPs is needed to improve the quality and outcomes of these certificates.26

Notably, simply developing guidelines for medical certificates might result in arbitrary decisions without considering the context in which the patient presents. A GP’s assessment of a client’s capacity is less of a technical matter and more of a normative one, meaning that doctors should be able to articulate their considerations and arguments in an ‘open manner’.27 Developing guidelines on medical certification, along with proper training for GPs on how to apply them in a manner that is open and flexible, can help GPs to improve the outcome for patients and health and social systems.

Discussion

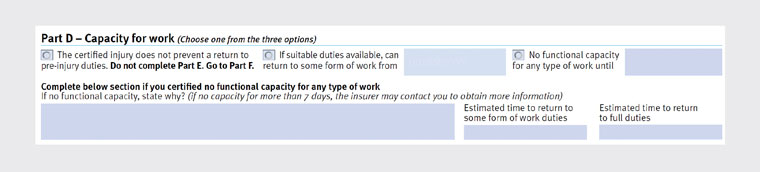

Here, two examples are presented, which come from two forms that are regularly completed by GPs as part of their medical certification. Both are constructed by authors based on similar responses reviewed for this article. The first one is the Work Capacity Certificate – Workers’ Compensation Form (132m),1 where we focus on two possible responses that could be produced only for Part D. This is where GPs are asked to certify that there is no functional capacity for any type of work and why (Figure 1). Table 1 compares a common response written for Part D with what the authors recommend.

The common response does not indicate an actual medical diagnosis and fails to consider the worker’s duties in assessing the functional capacity. This might confuse the Workcover agent who must make decisions based on such medical advice. In the recommended response, the words are chosen factually with detailed information necessary for an objective decision. It is, at the same time, not too detailed considering the time constraints GPs face.

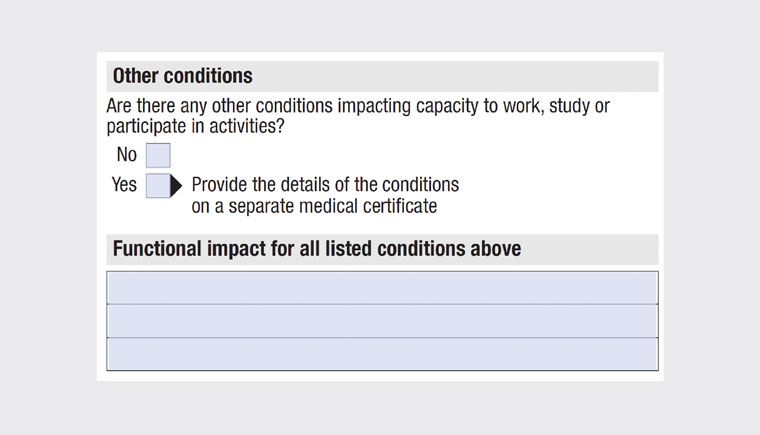

Figure 2 is taken from the Centrelink Medical Certificate form (SU415)2 where GPs are asked to write about the functional impact of all conditions related to the patient.

Similarly here, as shown in Table 2, the common response fails to address the symptoms of anxiety/depression and a medical diagnosis that might delegitimise one’s entitlement to sickness benefits. Nor does it explain how major depression affects the ability to perform work duties. Objective wording helps GPs balance their double role of assessor and advocate for their patients. When words sound objective and are based on a clear diagnosis, it makes a better impact on the reader (the other stakeholder) assessing the form. The fact that medical certificates are a written genre of communication by GPs makes it necessary to point out that, as shown in studies in linguistics, writing is permanent and as such, it is associated with authority and credibility.24 In addition, as it is written, this piece will accompany the patient through their passage in the healthcare system.28

Therefore, it is of utmost importance to consider the impact this communication makes on various parties in this process. For patients, participating in the process of medical certification and accessing social benefits can have a major impact on their livelihood and mental wellbeing.8 Fragmented interactions can impede recovery as patients feel that their entire situation is not being considered.6 This is echoed by injured workers in Australia who report that they deal with disengaged case managers, negative stereotyping, insufficient related information, suspicious reactions from all the stakeholders and a lack of professionalism in the communication from service providers.29 These challenges can hamper the recovery process and exacerbate the psychological toll on patients trying to navigate the complexities of medical certification.

Figure 1. Workers’ compensation form (132m).

Reproduced from the Queensland Government, WorkSafe. Work capacity certificate - medical providers. Queensland Government, 2020. Available at www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/service-providers/medical-providers/work-capacity-certificate, with permission from the Queensland Government.

| Table 1. Responses to Part D: Work capacity certificate – Workers’ compensation form (132m) |

| Question |

A common response |

Recommended response |

| ‘Complete below section if you certified no functional capacity for any type of work. If no functional capacity, state why’ |

After lower back injury, the worker is unable to perform their regular work duties |

The diagnosis of lumbar strain with associated muscle spasms prevents (this worker) from fulfilling the requirements of their role, which include frequent lifting of objects weighing up to 20 kg, prolonged periods of standing, and frequent bending and twisting motions |

Figure 2. Centrelink Medical Certificate form (SU415).

Reproduced from Australian Government, Services Australia. Centrelink Medical Certificate form (SU415). Australian Government, Services Australia, 2023. Available at www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/su415, with permission from the Australian Government, Services Australia.

| Table 2. Responses to the Centrelink Medical Certificate form (SU415) |

| Question |

A common response |

Recommended response |

| ‘Functional impact for all listed conditions above’ |

(Patient name) cannot work due to anxiety/depression |

(Patient name) is diagnosed with major depressive disorder causing feelings of sadness, hopelessness and worthlessness with increased irritability, difficulty concentrating and disrupted sleep patterns. These symptoms significantly impact her functioning and ability to perform her duties as an accountant effectively |

From a GP’s point of view, being the gatekeeper for sickness certification can adversely affect the doctor–patient relationship. GPs often find it impossible to reconcile the demands of the other stakeholders with the complexity of the patient’s needs.30 In contrast, the implementation of clinical criteria and standardisation might risk oversimplifying the evaluation process that overlooks the contextual reasoning and normative dimension of individual cases,23 resulting in an unwanted conflict for the doctor.31 Finally, the GP’s dual role as both advocate for the patient and arbiter of clinical judgment introduces an additional layer of complexity, potentially influencing the doctor’s objectivity in the certification process.32

Employers often believe that GPs have a poor understanding of the complexity of the Worker’s Compensation system. This belief is argued to be due to the common occurrence of incorrect, incomplete or inadequately detailed certificates received by employers.33 The deficiency in information extends to remuneration details and a lack of awareness about specific workplace conditions. Moreover, employers reported feeling excluded from the process while harbouring suspicions about injured workers exploiting the system.33 This disconnect between GPs and employers underscores the urgent need for improved communication channels.

Conclusion

The challenges faced by GPs in writing medical certificates are multifaceted and have significant implications for patients, the healthcare system, doctors and employers. The wording in certificates, the double role of GPs, and the need for further training all reduce the likelihood of a certificate accurately and fairly supporting a patient. Professional training programs for GPs are needed to provide the necessary knowledge and skills to improve communication and navigate the complexity of medical certification effectively. These must include clear guidelines, protocols and standardised procedures that provide clarity on certification criteria, appropriate wording and decision making. They need to be flexible for GPs to word the certificates in an open manner. It is important to highlight that the introduction of technology in producing medical certificates can facilitate the process. This can be a relevant topic for further studies and practice-focused special issues. The art of communication in terms of ongoing education in communication skills34 must extend to the written communications GPs make on a daily basis with clear consequences for the healthcare system and patients.

Key points

- The wording of medical certificates influences outcomes significantly, affecting patients’ mental health, financial wellbeing and recovery.

- GPs struggle with dual roles as advocates and assessors, which leads to conflicts and dissatisfaction in therapeutic relationships.

- GPs’ assessments of work-related issues require a nuanced approach to consider broader societal implications for better outcomes, hence highlighting the need for guidelines and training programs for effective communication.

- GPs are advised to choose factual words and expressions to describe the diagnosis, with detailed information necessary for an objective decision, considering the time constraints GPs face.

- Objective written communication that is based on a clear diagnosis makes a better impact on the reader (the other stakeholder) assessing the medical certificate.