Male genital dermatoses are nuanced and demanding presentations for general practitioners (GPs). Their diverse clinical presentations and cross-specialty referral pathways can be onerous to navigate. Recognising and initiating management in the primary care setting is critical, and determining when to seek subspecialist advice remains controversial. The interplay of diverse demographics, patient anxiety and overlapping signs and symptoms often complicate the diagnostic pathway. Social stigma and reluctance to seek medical attention is a common reason for delayed treatment. Accurately distinguishing between normal variations, benign presentations and potentially infectious or malignant conditions is paramount to reducing morbidity and improving public health.

Aim

We aim to provide an up-to-date and concise framework to guide clinicians in their risk stratification and decisions for treatment, and potential referral of these conditions.

History and examination

Establishing a safe and culturally sensitive rapport is paramount when assessing penile dermatological concerns.1 A thorough examination, using accurate descriptors of the dermatosis, is essential for documentation and potential referrals. Take note of circumcision status and location of the abnormality, and compare findings with the skin condition elsewhere on the body.2 Clinical photography with patient consent is a valuable diagnostic aid and is being increasingly used in artificial intelligence–augmented diagnostic tools.3

Non-malignant/non-infectious conditions

Normal penile dermatological variation

Normal genital skin variations are common and can produce anxiety for patients and physicians. It is crucial to distinguish normal variants from treatable pathology to minimise unnecessary investigations and alleviate patient concerns.

In circumcised males, the glans epithelium becomes keratinised, and might appear purple. Similarly, there are variations in scrotal colour and the hue of the midline raphe.4

Variations can be attributed to skin phototypes, ancestry/ethnicity and genetic factors. Although reassurance is adequate, pigmentation changes might also accompany inflammatory diseases, and normal pigmentation differences can impact a patient’s sexuality and psychological wellbeing.

Common benign presentations

Pearly penile papules are common, presenting as tiny pale papules localised to the coronal sulcus, and might form multiple rows (Figure 1A). Fordyce spots are ectopic sebaceous glands appearing as pale micropapules (Figure 1B).

Median raphe cysts are benign, pale, fluid-filled sacs along the scrotal raphae (Figure 1C). Angiokeratoma of Fordyce are vascular malformations appearing as tiny red–purple scrotal spots that might occasionally bleed (Figure 1D). These conditions do not require intervention, and offering reassurance and observation is safe.

Figure 1. Photographic examples of common benign penile dermatological presentations: (A) benign pearly penile papules; (B) Fordyce spots; (C) median raphe cysts; and (D) angiokeratoma of Fordyce.

Reproduced from Hall A. Atlas of male genital dermatology. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2019, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-99750-6, with permission from Springer Nature Switzerland AG.39

Red penile lesions

Genital disease is mostly non-infectious skin disease

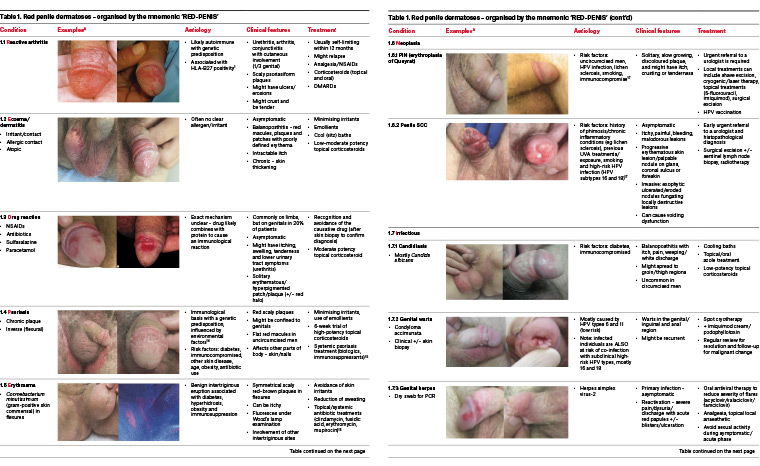

Isolated glans inflammation is termed balanitis, whereas balanoposthitis encompasses reactions involving the glans and foreskin. These terms describe red genital dermatoses but do not specify the underlying cause. The mnemonic ‘RED-PENIS’ is helpful for recalling these aetiologies (Table 1).

Table 1. Red penile dermatoses – organised by the mnemonic ‘RED-PENIS’. Click here to enlarge

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis is a multisystem autoimmune inflammatory condition with a genetic predisposition, characterised by urethritis, arthritis and conjunctivitis with cutaneous involvement (Table 1, section 1.1).5 It most commonly affects young men aged 20–30 years, preceded by a triggering infection.6

Eczema/dermatitis

Irritant dermatitis is common and is often misdiagnosed, especially in uncircumcised men (Table 1, section 1.2), as the preputial recess is an intertriginous site where skin rests against. Scrotal skin is particularly susceptible, and identifying a single causative agent is challenging.7 Uncontrolled skin inflammation over time can lead to lichenification, characterised by scaly, thickened skin with surface excoriation. Atopic dermatitis should be considered in association with previous atopy.

Allergic contact dermatitis of the male genital skin manifests as acute, severe dermatitis. A thorough history, patch testing and avoiding allergen exposure form the cornerstone of management.

Drug reaction

An immunological reaction to a range of drugs, causing a fixed reaction of variable cutaneous involvement (Table 1, section 1.3), occur on the genitalia in 20% of patients, and might be immediate or delayed up to one to two months.8

Psoriasis

Psoriasis affects approximately 3% of the population and 29–40% will experience genital manifestations (Table 1, section 1.4).9,10 Over two-thirds of men with chronic plaque psoriasis will experience genital involvement at some point in their disease course, characterised by salmon-red, scaly plaques. Genital psoriasis might occur independently but is frequently associated with inverse (flexural) psoriasis, often impacting the groin.11 Patient concern centres around appearance and negative impacts on sexual wellbeing. When diagnosis is uncertain, biopsy can rule out neoplasia, particularly for solitary glans lesions.12

Neoplasia

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) encompasses in situ squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and erythroplasia of Queyrat. PIN is a non-invasive, pre-malignant proliferation of cells demonstrating variable levels of abnormality including keratinisation and nuclear atypia (Table 1, section 1.6.1).13 This condition can be differentiated based on cell-turnover drivers, including lesions arising from human papillomavirus (HPV) infections and chronic inflammation.14,15 Diagnosis is made by biopsy or excision. Regular surveillance is crucial as the recurrence rate is nearly 50%; however, with adequate treatment only 2% will progress to invasive carcinoma.16

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis

Penile SCC is a rare but potentially aggressive malignancy that requires urgent management by a uro-oncologist (Table 1, section 1.6.2). The contemporary five-year survival for regionally advanced disease is 51%.17 Australian penile cancer incidence is <0.1 per 100,000 or approximately 300 diagnoses per year.18 Early treatment is paramount to penile-preserving intervention and survival. However, many men experience a treatment delay of more than six months due to social stigma, neglect and access to care, resulting in poorer outcomes.19 Palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy will be present in 28–64% of men at presentation, with almost 50% of these representing regionally advanced disease.19

Diagnosis is by excisional biopsy and minimally invasive sentinel lymph node biopsy.20 For low-risk penile SCC, early surgical intervention might be curative. There is a minimal role for chemoradiotherapy in physically fit patients with lymph node-positive disease.21,22 Radical lymphadenectomy offers the best outcomes for high-risk disease.23 Although more research is needed for this rare disease, recent data suggest that men experience better outcomes when managed by an experienced uro-oncology team at a high-volume tertiary hospital.24

Infections

Non-sexually transmitted

Opportunistic fungal infection is typically caused by the Candida species. Uncircumcised men with pre-existing immunocompromise are most at-risk

(Table 1, section 1.7.1).25 Diagnosis is confirmed through a skin swab. Effective treatment usually only requires a topical imidazole cream. Persistent candidal infection might require oral treatment agents.

Sexually transmitted

Approximately one in six Australians might contract an STI in their lifetime.26 Partner contact tracing should be conducted whenever possible. Genital warts (Condyloma acuminata) are common in the anogenital region, caused by specific types of HPV (Table 1, section 1.7.2). Although primarily attributed to HPV types 6 and 11, co-infection with high-risk types 16 and 18 can lead to malignant transformation.27 Treatments include cryotherapy, topical imiquimod and podophyllotoxin. There is no curative treatment as the virus embeds within host cell DNA.28 All patients should undergo partner contact tracing, and female partners should undergo a swab for HPV DNA detection. Routine vaccination of all adolescents with a HPV vaccination is an important public health measure to reduce the likelihood of infection.

High-risk individuals and those aged <26 years should receive the Gardasil-9 vaccine.29

Genital herpes (herpes simplex virus-2) can be confirmed on dry swab PCR (Table 1, section 1.7.3). Patients often present with first reactivation of the virus and can be effectively treated with topical or oral antivirals.

Primary syphilis (Treponema pallidum) in males typically presents initially with a painless chancre30 (Table 1, section 1.7.4), although these might be overlooked at examination if occurring in the oral mucosa or rectally. Untreated syphilis can ultimately affect many organ systems. High-risk groups include those engaging in unprotected sex with multiple partners and is more prevalent in men who have sex with men. Diagnosis requires a combination of serology and nucleic acid amplification tests from a lesion swab. Patients should be screened for co-infection with HIV.30

Sclerosis

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a multifocal inflammatory skin condition that occasionally presents on genitalia in both males and females (Table 1, section 1.8.1). Chronic ulcerative lichen planus can lead to genomic instability, increasing malignant potential.31 Careful monitoring and consideration of circumcision is critical for mitigating the risk of penile SCC.

Plasma cell balanitis (Zoon’s)

Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis) occurs in uncircumcised older males (Table 1, section 1.8.2). It might develop gradually over months to years and is generally asymptomatic.32 A biopsy is recommended to rule out inflammatory or premalignant conditions.

Genital dysaesthesia

Male genital dysaesthesia usually presents as a burning sensation of the genital skin, akin to vaginal vulvodynia (Table 1, section 1.8.3).33 In more severe cases, male genital dysaesthesia might be painful, resulting in dyspareunia and avoidance of sexual activity. Specialist referral is often warranted.

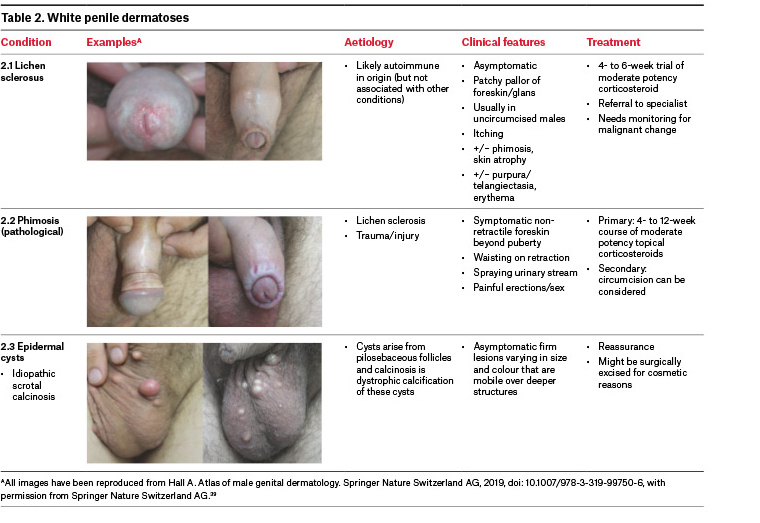

White lesions

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic, sclerosing inflammatory condition of uncertain cause of the anogenital skin (Table 2, section 2.1).34 Biopsy should be considered when the diagnosis is uncertain. Untreated cases with persistent phimosis and chronic inflammation can lead to malignant transformation, but there is debate on this issue. The lifetime risk of malignant transformation has not been established.35,36

Table 2. White penile dermatoses. Click here to enlarge

Phimosis

In Australia, circumcision rates have declined, dropping from a peak of 85% in the 1950s to 19% in 2019.37 Physiological phimosis is normal at birth and might variably persist in children. Phimosis is considered physiological if penile function or voiding are unaffected.38

Pathological phimosis exists when the foreskin remains non-retractile beyond puberty, resulting in problematic voiding or dyspareunia (Table 2, section 2.2). Retraction of a pathologically phimotic foreskin might lead to a tight ‘waisting’ of the band around the glans or penile shaft.38

Lichen sclerosus with phimosis can lead to pinhole phimosis, causing painful erections and dyspareunia, and rarely urinary obstruction or recurrent infections, requiring circumcision.34

Investigations

All investigations for genital skin lesions are specific to the suspected pathology and should be considered in the setting of detail history and examination (Table 3). Histopathological analysis is an invaluable diagnostic tool for penile skin dermatoses. It is crucial to rule out premalignant or malignant disease, but histopathology might have limitations in interpretation of inflammatory lesions (Figure 2). The commonest complications of genital skin biopsies are vasovagal reactions, bleeding and scarring. All biopsies should be performed after informed consent is obtained, under local anaesthetic, in a sterile fashion.

| Table 3. Investigations and procedures useful for the diagnosis of penile dermatoses in the general practice setting |

| Investigation |

Examples |

Procedure |

| UVA (Wood lamp) |

- Erythrasma

- Pigmentation disorders

- Fungal infection

|

Utilising UV light from different sources from mercury vapour to LEDs. A range of pathologies fluoresce variably under UV light |

| Bedside microscopy |

|

A microscopic examination of skin scraping might reveal

skin mite/insect infestation |

| Skin swab/laboratory MCS |

- HSV

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Chlamydia trachomatis

|

Useful for bacterial/fungal infections. Might also increase detection of STIs through NAT PCR |

| Serological testing |

|

Screening for underlying STI, if indicated. Completion screening for other STIs is mandatory if one is found |

| Skin patch testing |

- Allergic contact dermatitis

|

Patch testing against common allergens |

| Procedure |

Indication |

Technique |

| Punch biopsy (3–4 mm) |

- Non-pigmented lesions of glans

- Suspected non-malignant lesions

|

Rotate the disposable punch biopsy without pressure. Elevate the specimen with a needle and cut the specimen at proximally. An absorbable suture might be used for haemostasis |

Deep incisional biopsy

Excisional biopsy |

- Suspicion of invasive cancer

- Pigmented lesions

|

Using a small blade, excise the lesion with some normal tissue around it (skin margin), in an elliptical fashion. An absorbable suture(s) might be used for haemostasis |

| Shave biopsy |

- Pigmented lesions

- Lesions on the penile shaft

|

A flexible razor or scalpel might be used to shave the lesion. Chemical haemostasis might be utilised in this type of biopsy |

| Curette/snip biopsies |

|

A blade might be used to remove a lesion on a stalk |

| HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; LEDs, light emitting diodes; MCS, microscopy culture and sensitivity; NAT PCR, nucleic acid testing by polymerase chain reaction; STI, sexually transmitted infection; UV, ultraviolet; UVA, ultraviolet A. |

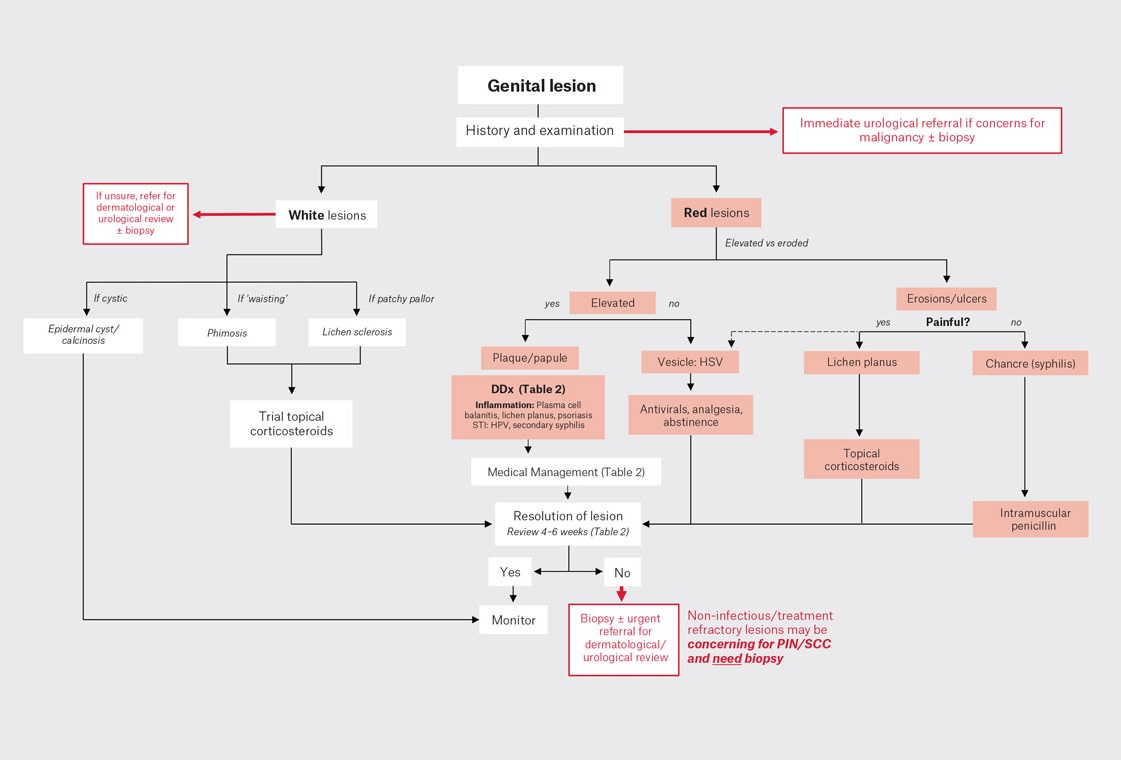

Figure 2. Simplified algorithm for approach to genital lesions.

HSV, herpes simplex virus; PIN, penile intraepithelial neoplasia; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

Urological dermatology can be a complex area for general practitioners and urologists, as it encompasses diverse pathology with overlapping clinical presentations. Fortunately, many can be effectively managed in a primary care setting. However, considering a biopsy or seeking multidisciplinary specialist guidance is crucial if there is uncertainty in diagnosis or if initial treatments do not lead to timely improvement. This proactive approach will alleviate patient anxiety and ensure optimal care.

Key points

- Normal variations and appearance in genital skin are common and might cause unnecessary anxiety for patients and physicians alike.

- Genital skin disease is mostly non-infectious in aetiology.

- Pathological phimosis is best treated with upfront topical corticosteroid therapy referred for consideration of circumcision if refractory.

- Opportunistic screening and prevention of STIs should be undertaken whenever appropriate, especially in the context of co-infection.

- Genital skin biopsy is essential to confirm or rule out penile neoplasia.