Heart-wrenching images of acute injuries, death and destruction are front page news in disaster media, but look further and a broader health cost emerges; a cost that changes lives and communities forever. One that influences individual physiology, the trajectories of human lives and even the next generation. Reflecting their huge impact on societies and individuals, disasters are sometimes labelled a social determinant of health. They precipitate physical, mental and social health effects that compound each other and have long-lasting effects.

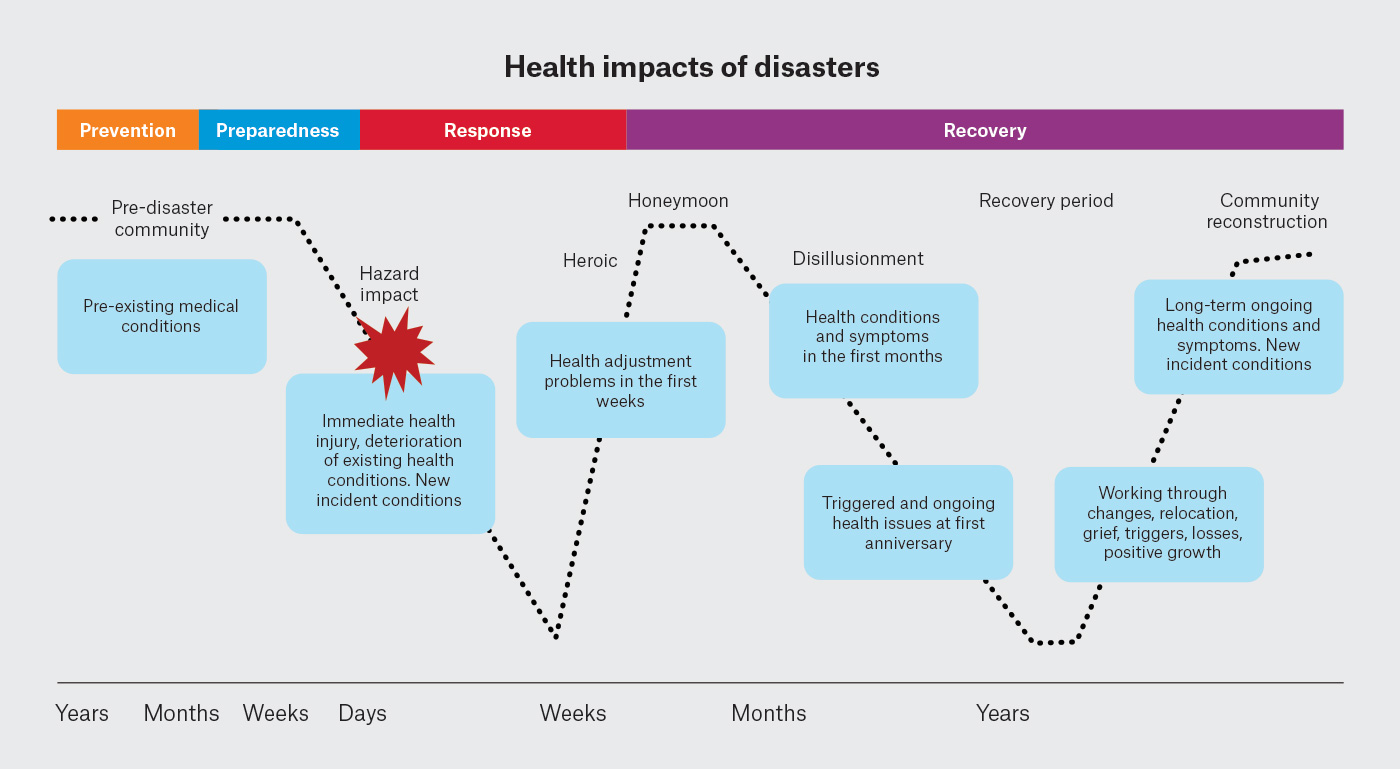

Disaster health effects can be direct (eg drowning in a flood) or indirect (eg deterioration of pre-existing disease due to loss of medications). Health effects can be seen over immediate (hours to days), medium-term (weeks to months) and long-term (months to years) periods following an acute disaster incident (Figure 1, Table 1). Despite minor patterns attributable to the hazard type, the majority of health effects are predictable and consistent across hazard types, with the substantial volume falling clearly within the scope of general practice.1 If general practices remain open, these healthcare needs can be managed to avoid overwhelming emergency departments (EDs) and disaster teams. Over a two-week period following Hurricane Katrina, local general practitioners (GPs) in Texas established a clinic that treated 45% of 3700 evacuees. Over the same period, 0.04% evacuees presented directly to hospital with mainly minor complaints.2 GPs are well-placed to provide continuity and a holistic approach to disaster healthcare.

Figure 1. Phases of disasters with stages of community adaptation and disaster health considerations.3

Figure 1. Phases of disasters with stages of community adaptation and disaster health considerations.3

Adapted from Burns PL, Douglas KA, Hu W. Primary care in disasters: Opportunity to address a hidden burden of health care. Med J Aust 2019;210(7):297–99.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50067, with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

| Table 1. Potential disruptions to healthcare service provision9 |

| Immediate/short term (hours–days) |

Medium term (weeks–months) |

Long term (months–years) |

| Healthcare provision disruption |

|

|

| Disease surveillance |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

| Reduced routine healthcare (eg chronic care review and medications) |

Ongoing |

|

| Reduced specialised healthcare (eg dialysis) |

Ongoing |

|

| Reduced preventative care |

Ongoing |

|

| Surge in patient load |

|

|

| Healthcare infrastructure disruption |

|

|

| Damage to healthcare infrastructure |

Variable duration |

|

| Reduced medical equipment supplies/resources |

Variable duration |

|

| Reduced healthcare staff |

Variable duration |

Variable duration |

| Difficult physical access to healthcare services (transport disruption, physical barriers [eg earthquake]) |

Variable magnitude |

|

| Loss of financial viability of healthcare services |

Variable magnitude |

Variable magnitude |

| Utility disruption |

|

|

| Power disruption |

Variable magnitude |

|

| Water disruption or contamination |

Variable magnitude |

|

| Sanitation/waste removal |

Variable magnitude |

|

| Evacuations |

|

|

| Change in local population and health needs |

Variable magnitude |

Variable magnitude |

| Environmental hazards |

|

|

| Animal bites, particularly domestic |

Variable duration |

|

| Insect bites and mosquito vectors |

Ongoing |

|

Aim

This article reviews the evidence on disaster health effects from an all-hazards perspective and highlights the essential role of general practice in disaster healthcare.

Disaster health effects

Disasters affect health across all body systems and result in increased morbidity and mortality within affected communities. Heatwaves have the greatest mortality rate of disasters in Australia and globally. Over 60,000 excess deaths occurred in Europe during the 2022 summer.4,5 Floods are the second most deadly disaster in Australia. A review of 35 global epidemiological studies identified increases in mortality rates of up to 50% in the first year, post-flood.6

Accompanying increased mortality is increased morbidity, with chronic diseases representing the greatest burden. Increased rates of diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events (CVA) and asthma are all seen in disaster-affected communities (Table 2). Pre-existing conditions do not go away during disasters; in fact, they tend to deteriorate and require additional medical management.1,7,8 The effects of acute stress, loss of medications and monitoring equipment (eg diabetic testing kits) and altered activity and diet, can all impact disease control and in some instances become life-threatening emergencies. Compounding these health effects are disruptions to healthcare infrastructure and services including life-sustaining services such as dialysis (Table 1).

In the first days of disasters, a significant increase in presentations of acute exacerbations of chronic diseases to overcrowded medical facilities is seen for hypertension, myocardial infarction, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, routine scripts and drug dependence. Those with multiple comorbidities face greater risks.7,8 Individuals with chronic conditions are also more likely to present with a separate acute condition that might also adversely affect their underlying chronic condition.8,10,11 Key disaster health effects relevant to general practice are outlined in Table 2 and summarised below.

| Table 2. Key disease patterns, associated with disasters, relevant to general practice healthcare provision12–15 |

| Immediate/short term (hours–days) |

Medium term (weeks–months) |

Long term (months–years) |

| Health impacts |

|

|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

| ↑ BP and HTN |

↑ BP and HTN |

Deterioration HTN to 4 years |

| ↑ MI |

↑ MI peak first 2.5 weeks |

↑ MI 2.5 weeks to 5.5 years

(↑ 3xs 4 months to 2.5 years) |

| ↑ Mortality due to IHD |

↑ Mortality due to IHD first 2.5 weeks |

↑ Mortality due to MI 1.5 to 3.5 years |

| ↑ SCM |

↑ SCM to 2 weeks |

|

| ↑ CVA |

↑ CVA to 2.5 months |

↑ CVA to 3 years |

| Deterioration HF |

Deterioration HF |

Deterioration HF to 3.5 years |

| ↑ PE |

↑ PE to 3.5 weeks |

|

| ↑ NCCP |

↑ NCCP to 2.5 weeks |

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

| ↑ Tsunami lung |

↑ Pneumonia |

↑ Pneumonia to 12 weeks |

| Carbon monoxide poisoning |

↑ Pneumonia mortality |

↑ Pneumonia mortality to 12 weeks |

| ↑ Respiratory ED presentations first days |

|

|

| ↑ Respiratory hospitalisations |

|

↑ New sinusitis to 9 years |

| ↑ Asthma exacerbations |

↑ Asthma exacerbations to 5 weeks |

↑ New asthma to 10 years |

| ↑ COPD/chronic bronchitis exacerbations |

|

↑ New lower respiratory symptoms to 16 years |

| Endocrine |

|

|

| ↑ New incident DM |

|

↑ New incident DM to 10 years (associated with PTSD) |

| Deterioration of existing DM |

↑ HbA1c 6 weeks to 16 months |

↑ HbA1c 6 weeks to 16 months |

| ↑ Exacerbations of DM to ED |

↑ Exacerbation of DM to ED to 2 weeks |

|

| ↑ Gestational DM |

↑ Gestational DM |

|

| ↑ All-cause mortality in DM |

↑ All-cause mortality in DM to 1 month |

|

| Infectious disease |

|

|

| Wounds/injuries in clean-up |

Wounds/injuries in clean-up |

|

| Cellulitis/tetanus in wounds |

Cellulitis/tetanus in wounds |

|

| Herpes simplex first months |

Herpes zoster 5th month |

| Outbreaks of local infectious disease (eg influenza, gastroenteritis) |

|

|

| Skin/eye/ear conditions |

|

|

| Animal bites – domestic and native |

|

|

| Burns – electrical, bushfire |

|

|

| Dermatitis, urticaria, folliculitis |

Dermatitis |

|

| Eye infections/foreign bodies (ash) |

|

|

| Hearing damage (explosions/bomb blasts) |

Hearing damage |

Hearing damage |

| Gastrointestinal disease |

|

|

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

|

| Musculoskeletal effects |

|

|

| Traumatic muscular injury |

Chronic musculoskeletal conditions |

Chronic musculoskeletal conditions |

| Fractures – limbs, spinal |

Ongoing rehabilitation |

Ongoing rehabilitation |

| Loss of limb |

Ongoing rehabilitation |

Ongoing rehabilitation |

| Sarcopenia due to decreased intake |

|

| Mental health |

|

|

| Psychological distress |

Psychological distress in first weeks |

|

| Sleep disorder |

Sleep disorder |

Sleep disorder |

| Acute stress disorder |

PTSD |

| Exacerbation of pre-existing mental health conditions |

Anxiety, depression |

Anxiety, depression

Persistent complex bereavement disorder |

| Exacerbation substance misuse (alcohol/illicit) |

Ongoing substance misuse |

Ongoing substance misuse |

| BP, blood pressure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; ED, emergency department; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1C; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; NCCP, non-cardiac chest pain; PE, pulmonary embolism; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SCM, stress cardiomyopathy; 3xs, tripling in the expected incidence of MIs in this period compared with predisaster. |

Cardiovascular effects

The incidence of cardiovascular disease including myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, pulmonary embolism and cerebrovascular accident (CVA), all increase following disaster (Table 2). Deterioration in existing cardiovascular conditions is also seen, including hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.16 Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), also known as broken heart syndrome, is a stress-induced cardiomyopathy thought to be caused by acute catecholamine release. During the 2010–11 Christchurch earthquakes, there were 27 hospital admissions for TCM, alongside MIs and non-cardiac chest pain in the first two weeks following the disaster.17

Respiratory effects

The 2001 World Trade Centre (WTC) attacks led to greater understanding of the damaging respiratory effects of disasters from particulate matter (PM). Toxic aerosolised matter from the crash and prolonged clean-up caused greater morbidity and mortality than initial traumatic injuries. Increased incidence of asthma and deterioration in pulmonary function were seen in children and adults living or working in the area, who had persistent lower respiratory symptoms (LRS) for well beyond a decade.18

In Australia, bushfire smoke is a significant cause of disaster-related morbidity. Bushfire smoke during the unprecedented 2019–20 Australian Black Summer bushfires was associated with an excess 417 deaths, 1124 hospitalisations for cardiovascular disease, 2027 hospitalisations for respiratory problems and 1305 asthma presentations to emergency rooms.19,20 Dust storms and thunderstorm asthma events are other disasters in Australia that impact respiratory health.

Respiratory morbidity might also result from infrastructure and utility failure. Carbon monoxide exposure risk increases during blackouts due to indoor grilling, inappropriate generator placement and residential fires.21

Endocrine effects: Diabetes

Increased risk of new onset diabetes, and deterioration of existing diabetes, have been seen following disasters, and can persist for many years. For example, a significant increase in prevalence of diabetes (9.3% to 11.0%) was seen in the 1.5 years after the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami.22 Additionally, a 40% increase in all-cause mortality was seen in the first month post Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in older people with diabetes, and was highest among evacuatees.23

Individuals at higher risk of experiencing worse diabetes-related outcomes include those using insulin, those with concomitant mental health conditions and those without access to healthcare services. Pregnant women are at risk of gestational diabetes. Evidence from the Hull Floods in England24 and Hurricane Katrina16 suggests that early healthcare review can optimise glycaemic control by six to nine months, rather than ongoing deterioration over 1.3 years.16,24 This highlights the importance of ongoing general practice review post disasters.

Infectious disease risk

Infectious disease presentations tend to occur days to weeks following disasters. Large-scale outbreaks due to natural disasters are uncommon in higher-income countries such as Australia, unless the disaster is an infectious outbreak itself. If outbreaks do occur, they usually result from endemic, rather than novel, organisms, with acute respiratory infections and gastroenteritis being the most frequent. Disruption to water and sanitation, population displacement and crowding in evacuation centres, and pre-event population susceptibility contribute to increased risk of waterborne, foodborne or respiratory diseases post disaster. Appropriate vaccination for tetanus, influenza, pneumoccocus, pertussis, measles, respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2 and herpes zoster is recommended.

Skin effects

Inflammatory disease, trauma and burns are common following disasters. Irritant contact dermatitis, urticaria and folliculitis can occur in those working and living in the post-incident environment.25 Injuries can occur during the acute incident and clean-up period. Common presentations include puncture wounds, lacerations and domestic animal bites.26 Burns and smoke inhalation injuries are risks during bushfires.27

Health effects on other body systems

This article has considered those body system that are most affected by disasters. However, all systems are impacted. GPs treating patients affected by disasters need to consider a broad range of potential health effects. For example, gastroesophageal reflux disease was one of the most prevalent presentations in the first days following the WTC attacks.28 An increase in hospital admissions and mortality due to renal failure has also been documented as a result of disasters.29

Mental health

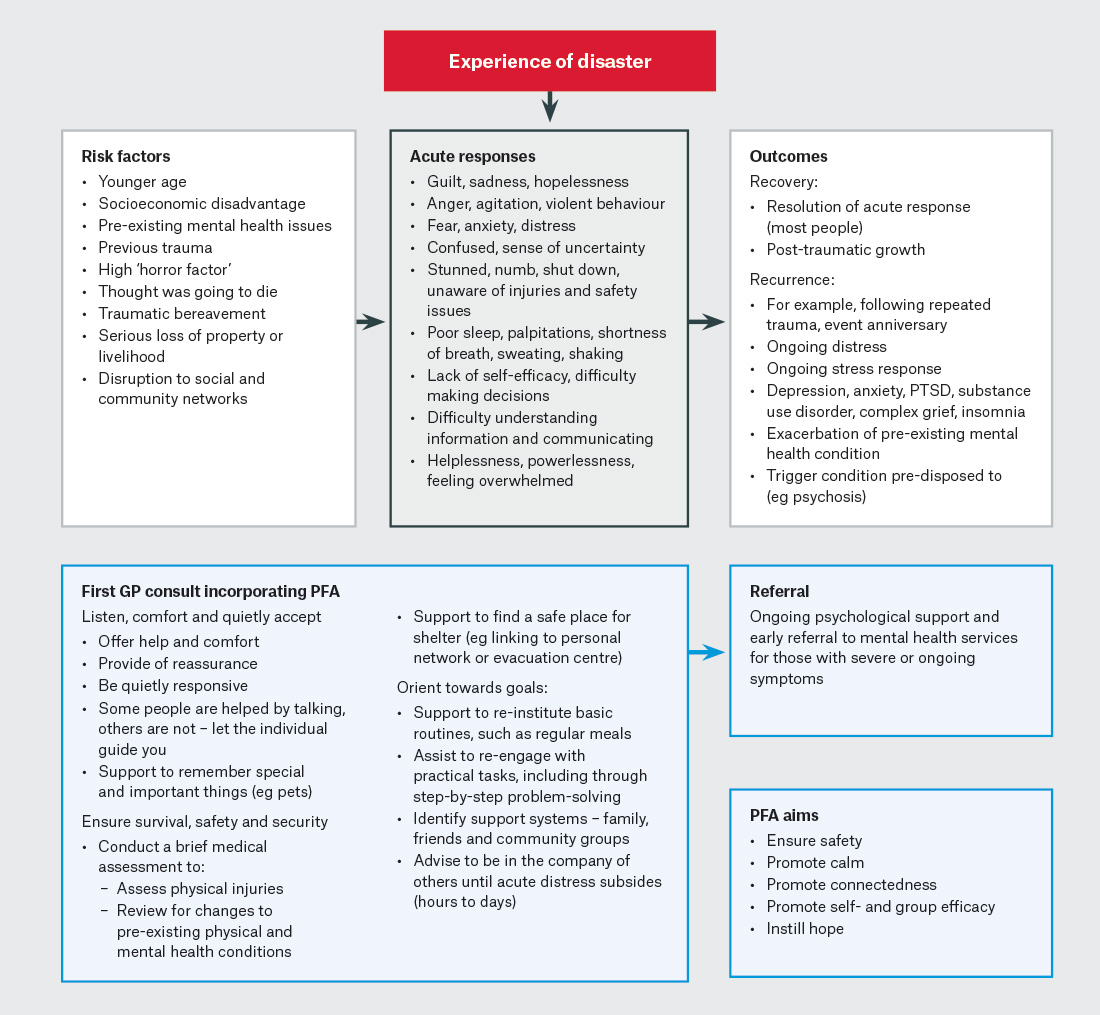

Many individuals experience psychological distress following disasters. Common responses are outlined in Figure 2. These reactions usually occur in the days to weeks after the event, but onset might be delayed and can differ for adults and children. Most individuals recover without ongoing mental health effects.30 Some individuals even experience post-traumatic growth, characterised by drawing new meaning from their experience and positive psychological changes including coping, altruism, helping others and gratitude.30 However, in the months and years following disasters, some individuals experience persistent or progressive symptoms and need ongoing psychological support and specialist referral (Figure 2). A meta-analysis of Australian communities affected by bushfires found a 14% pooled prevalence of psychological distress two to four years after each event.31 Risk factors for more pronounced mental health effects are outlined in Figure 2.32 Increased alcohol and illicit substance use has been shown to occur post disaster,33 but predominantly affects those with a previous diagnosis of substance use disorder.34

Figure 2. Mental health responses to disaster and general practice approaches incorporating principles of psychological first aid.30,32,33,35

GP, general practitioner; PFA, psychological first aid; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

For GPs managing psychological distress during a disaster, psychological first aid (PFA) is a valuable evidence-informed approach that aims to: ensure safety, promote calm, promote connectedness, promote self-efficacy and group efficacy, and instil hope. Figure 2 outlines a suggested approach to GP consultations incorporating PFA during disasters.32 For some people, skills for psychological recovery are a useful secondary prevention strategy. This evidence-informed approach builds skills and capacity to cope with distress and adversity in the weeks to months following a disaster. It was utilised successfully by GPs during the 2009 Victorian bushfires and focuses on building problem-solving skills, positive thinking, activities and social connections, as well as managing reactions.35 A minority of individuals will still need referral to mental health services for treatment.

Higher-risk populations

GPs know their higher-risk patients. They can monitor and support them to prevent deterioration during disasters. Particular higher-risk groups include the elderly, the pregnant, those with chronic disease and evacuees. This section focuses on specific considerations for GPs in supporting older individuals and those with chronic conditions.

The largest burden of disaster health effects relates to chronic disease. The high prevalence of chronic diseases in populations globally increases susceptibility to health effects during disasters.7,36 The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–30 recognises the particular need to address chronic disease in disaster management and planning.37 Table 3 summarises key healthcare and medication issues for those with chronic conditions during disasters. Perhaps the predominant issue for this population group is medication management, with substantial disruption that can continue for months. Both supply and adherence (even when supply is available) have been shown to be impacted following disasters and to translate to poorer health outcomes.38

| Table 3. Chronic disease healthcare needs during disasters1 |

| General healthcare needs among individuals with chronic disease during disasters |

Actions for GPs |

| GPs provide crucial ongoing preventative care and management of chronic conditions that can improve health outcomes in the recovery and longer term |

| Increase acute exacerbations of chronic conditions (three- to four-fold) and deterioration in chronic disease parameters |

Expect exacerbations of chronic conditions. Undertake active surveillance and more frequent review of patients with chronic conditions and prepare patients by updating management plans |

| Increased presentations by patients with acute conditions compared to those without chronic disease |

Respond to acute presentations and use this as an opportunity to proactively review chronic disease management |

| Increased requirement for healthcare services, medications and medical supplies, particularly among individuals with a greater number of comorbid chronic conditions |

Plan for and institute mechanisms to maintain access to medical review, essential medications and medical supplies. Implement targeted support for those with multiple comorbidities |

| Need for ongoing access to specialised healthcare facilities (eg dialysis units or opiate dispensing) |

Identify those affected by disruption to specialised healthcare needs and provide support to finding alternative options. This might include increased monitoring for complications, instituting temporising management and coordinating with emergency services to organise targeted access or evacuation |

Medication needs among individuals with

chronic disease during disasters |

Actions for GPs |

| Medication needs represent a major element of the management of individuals with chronic disease during disasters that require specific logistical planning |

| Altered medication type and/or dosage requirement due to deterioration in condition or development of new conditions |

Be aware of the need for regular review and adjustment of medications in those with chronic conditions |

| Poor medication adherence particularly in males, older people and evacuees |

Active surveillance for patient adherence to medications. Consider proactive messaging (eg via social media or SMS) |

| Evacuees without a usual GP are at higher risk of poor medication access |

Institute checklists for evacuees that include whether individuals have adequate medication supplies and systems to monitor medication receipt |

| Compromised medication integrity due to flooding or extremes of temperature |

Check and renew any medication affected by the disaster, including extreme heat (often undetected) |

| Poor access to specialised medication, particularly opiates and highly specialised drugs, from pharmacists, GPs and specialised units |

Ensure clear up-to-date documentation of medications for patients who might need to seek medical supplies from new doctors/pharmacists who are not familiar with their condition and needs |

| GPs, general practitioners; SMS, short message service. |

Older people and evacuation

Older people have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality during disasters and in the subsequent months post disaster.39 This includes greater burden of chronic disease effects; increased exacerbations of these conditions; greater difficulty accessing healthcare services; increased hospitalisations; risk of cognitive decline during evacuation; and increased mortality. Morbidity was significantly increased in older people in the first three months following Hurricanes Katrina40 and Sandy.39 Evacuation, relocation and disruption to social networks, diet and exercise activities all contribute.

Conclusion

Disasters are associated with substantial increases in morbidity and mortality alongside disruption to healthcare systems, communities and social determinants of health. The majority of disaster health effects fall within the scope of general practice. A holistic bio-psycho-social-ecological response is essential in disasters, as wellbeing depends on psychological and physical health, safety, social connectedness and environmental context. GPs’ specialist knowledge and understanding of their patients and the local health context means they have the capacity and duty to improve patient outcomes and reduce the disaster health burden.

Key points

- As the number of local communities being struck by disasters increases, GPs’ exposure to disasters and involvement in disaster health management is simultaneously increasing.

- To respond to this need, GPs need to urgently prepare for their role in disaster health management before disaster strikes their local community; once the disaster has arrived, it is often too late.

- The disaster health burden presents as a predictable pattern of healthcare needs arising from new and chronic conditions during and after disasters, with the majority of effects consistent across hazard types.

- The substantial burden of disaster medicine falls clearly within the realm of general practice.

- Managing deterioration, exacerbations, routine care and preventative care for those with chronic conditions is a key role for GPs, which is currently poorly integrated into disaster health management.