In 2015, the Australian Primary Health Care Advisory Group recommended establishing Health Care Homes (HCHs) to improve complex and chronic disease care.1 Subsequently, all Australian states agreed to support implementation.2 Multiple trials based on Medical Home models are underway.3–7 The Federal Government’s HCH trial is prominent among these.3

The HCH trial reorganises Australian primary care from a predominantly fee-for-service–based health insurance scheme to one in which people with chronic diseases attend the practice for all primary care and nominate a clinician (general practitioner [GP] or nurse practitioner) to lead their care team.8 A shared care plan is developed and electronically accessible to the patient and their healthcare providers. Bundled practice payments, stratified into three tiers on the basis of patient complexity, replace the fee-for-service model. Acute care remains fee-for-service.

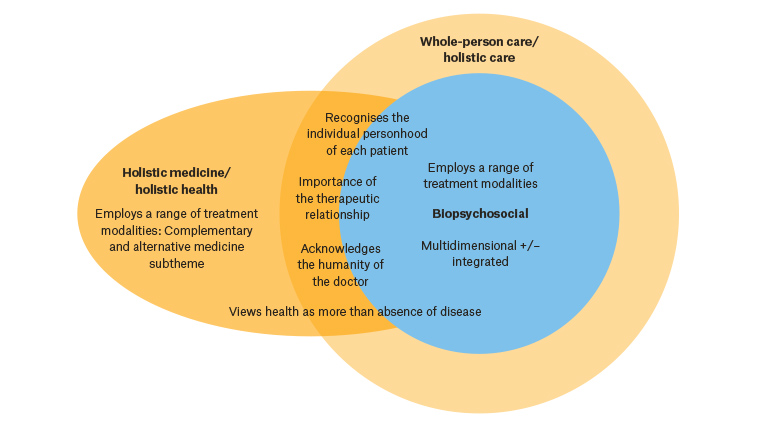

Ideally, HCHs should facilitate whole-person care (WPC) as foundational to general practice.9 A previous systematic review conducted by this research team found that WPC considers multiple dimensions of the person in an integrated way, values the therapeutic relationship, recognises patients’ individual personhood, acknowledges doctors’ humanity, views health as more than absence of disease and employs a range of treatment modalities (Figure 1).10 Subsequently, the researchers studied how Australian GPs understand WPC, perceived facilitators and barriers to WPC, and how GPs anticipate the government’s HCHs will affect the provision of WPC. This article reports findings for the latter aim and provides unsolicited broader perspectives on the HCH trial.

Figure 1. The elements of whole-person care, and its relationship to biopsychosocial and holistic care.10 Themes placed on circles’ boundaries are features of both terms, but more prominent in the term represented by the outer circle.

Methods

Researcher expertise comprised general practice, palliative care and ethics. Qualitative methodology allowed rich exploration of GPs’ views. Recruited participants were GPs and general practice registrars practising in Australia. Practices were selected from the government’s register of HCHs participants across all participating Australian states and territories. The researchers then approached Primary Health Networks to advertise the study, and used personal, educational and The University of Queensland’s teaching networks to recruit GPs not involved in HCHs, employed snowball sampling, and purposively recruited for demographic breadth. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire and one 20–45-minute semi-structured interview, conducted by HT, investigating their understanding of WPC, its facilitators and barriers, and expected impact of HCHs on the provision of WPC. The interview schedule was piloted and then modified inductively throughout data collection. Twenty interviews, including 18 by telephone, were conducted between May and November 2018. Theoretical saturation was reached concerning HCHs’ anticipated impact on WPC. Interviews were recorded and transcribed by professionals. The researchers analysed data concerning HCHs using thematic analysis.11 Two researchers (HT and either GM or MB) independently performed initial coding. Themes were developed with discussion and consensus between the researchers. NVivo 11 software (QSR International) assisted analysis.

Ethics approval was obtained from The University of Queensland’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2018000558).

Results

Study sample

Nineteen GPs and one general practice registrar from 17 practices were interviewed (Table 1). Seven of these GPs had HCH experience: four were participating in the pilot (coded as ‘HGP’ in results below), two had or were about to withdraw because of administrative challenges (‘wHGP’), and one was soon to commence (‘cHGP’). The remaining 13 GPs were not involved in HCHs (‘GP’).

| Table 1. Participant characteristics |

| HCH pilot involvement* |

Yes (n = 7) |

No (n = 13) |

Total (n = 20) |

| Female |

3 |

6 |

9 |

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

| 30–45 |

3 |

4 |

7 |

| 45–60 |

2 |

7 |

9 |

| >60 |

– |

2 |

2 |

| Not stated† |

2 |

– |

2 |

| Involvement in HCH pilot |

|

|

|

| Ongoing involvement |

4 |

– |

4 |

| Previously withdrawn/soon to withdraw |

2 |

– |

2 |

| Soon to commence |

1 |

– |

1 |

| Not involved |

– |

13 |

13 |

| Professional memberships |

|

|

|

| RACGP |

4 |

11 |

15 |

| RACGP and ACRRM |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| No college membership |

– |

1 |

1 |

| Not stated† |

2 |

– |

2 |

| Years practising medicine |

|

|

|

| 5–9 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

| 10–19 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

| 20–30 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

| >30 |

– |

6 |

6 |

| Not stated† |

2 |

– |

2 |

| Years practising as a GP |

|

|

|

| 0–4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 5–9 |

– |

3 |

3 |

| 10–19 |

3 |

– |

3 |

| 20–30 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

| >30 |

– |

4 |

4 |

| Not stated† |

2 |

– |

2 |

| State |

|

|

|

| Qld |

2 |

11 |

13 |

| NSW |

– |

1 |

1 |

| Vic |

– |

– |

– |

| TAS |

1 |

– |

1 |

| NT |

1 |

– |

1 |

| SA |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| WA |

1 |

– |

1 |

| ACT |

– |

– |

– |

| Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Area24 |

| RA1 |

3 |

12 |

15 |

| RA2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| RA3 |

3 |

– |

3 |

*HCH pilot involvement includes: GPs working at practices that are currently participating in HCHs (five GPs from four practices, including one GP soon to withdraw from trial), soon to commence HCHs (1 GP) or previously withdrawn from HCHs (one GP).

†Two GPs did not return the demographic information form; their responses are recorded as ‘not stated’

–, none; ACCRM, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine; GP, general practitioner; HCH, Health Care Home, RA, remoteness area; RACGP, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners |

Analysis of responses

GPs’ familiarity with and attitudes toward HCHs varied. Among HCHs participants, even GPs within a single practice expressed different attitudes towards the trial. The prevailing view, however, was that while the model had positive aspects, the government’s trial was limited by structural and practical constraints.

Three themes were identified (Table 2):

- aspects of HCHs may support WPC

- elements of the government’s HCHs model impede WPC

- there are practical struggles relating to HCHs.

Each theme was identified in both HCH and non-HCH participant interviews, though with subtle differences in emphasis, as discussed.

| Table 2. Themes and subthemes |

| Theme |

Subthemes |

| Aspects of HCHs may support WPC |

Continuity

Flexibility

Team-based care

Multidimensional care |

| Elements of the government’s HCH model impede WPC |

HCHs’ limited scope fragments care

Limitations of capitation funding |

| Practical struggles relating to HCHs |

Inadequate funding

Practice restructure

Technological issues |

| HCH, Health Care Homes; WPC, whole-person care |

1. Aspects of Health Care Homes may support whole‑person care

Several GPs supported principles underlying HCHs, though many did not support the government’s HCH trial concept.

… I think in principle [HCHs are] … an extremely good idea. (HGP02)

… I think that the idea [of HCHs] is great … but the government version of it is … really just a cost-cutting exercise ... (GP06)

Participants believed HCHs principles could potentially support WPC by facilitating continuity, flexibility and multidimensionality of care, and team-based care.

Continuity

GPs believed that WPC required continuity and that patient registration with HCHs encouraged this. Lack of continuity resulted in GPs being unaware of care provided elsewhere, compromised preventive care and was economically nonsensical.

… I used to find that people would … go to a local medical centre for easy stuff … and then present for … their complex … or … emotional needs … you weren’t aware that they had a certain illness … it really did decrease the ability to do WPC … [HCHs] would certainly streamline medicine beautifully. (GP11)

… [Currently] our government … would pay for any of us to go to 20 different general practices on the same day, [which] … doesn’t make any sense at all. (GP08)

However, some GPs believed that patient education and attention to the doctor–patient relationship would facilitate continuity better than HCHs.

… I think if you have a good therapeutic relationship about their chronic condition, you do get that WPC anyway. (GP03)

Flexibility

Participants identified that capitation funding could enable flexible and innovative care, facilitating the individualisation characterising WPC. Examples included opportunities to provide non–face-to-face care and introduce group allied health sessions.

… If we’re actually able to do things without being rigid with the Medicare rules … about time or being face to face … then it actually means we can start to address those things a bit better … we can really tailor to what the person needs or wants. (HGP01)

This was patient dependent, however; one GP believed that patients may not accept telephone consultations and that building relationships was essential prior to implementing HCHs.

… [Y]ou can’t start doing [HCHs] before you have this relationship with [the] patient … I think it does not work because patients are not interested in phone care … But if patients are happy, it’s easier for us. (HGP04)

One GP practising in an HCH identified that introducing flexibility requires experience with the model.

[The practice hadn’t] really got enough experience [with HCHs] … to start … innovative stuff … nowhere near that. (HGP03)

Emphasis on flexibility was stronger among HCH participants. Several non-HCH participants believed that introducing HCHs would not practically change their care, as they already provided flexible approaches. One reflected that they were able to do this because of their private billing structure.

… [W]e’re already providing that level of care on a fee-for-service basis … for a lot of other practices [HCHs] might be a good idea … but we’re already providing that. I couldn’t see how it was going to benefit my patients and I could see that I was going to actually earn less money. (GP02)

Team-based care

Participants identified that team-based care characterised WPC. Several believed HCHs would facilitate team-based care centred on the general practice.

… [T]hat was where I was really interested in the HCH approach … because it … allowed people to move toward holistic- type healthcare. Getting everybody involved, having a team approach … Working together … and … having funding from Medicare to be able to do that. (wHGP02)

Many participants stated that team-based care enhanced the therapeutic relationship and multidimensionality characterising WPC. They identified value in patients having relationships with multiple team members.

… [Patients] do develop that … therapeutic relationship with the nurses just as they do with the doctors. (wHGP02)

However, one HCH GP experienced less engagement with the patient when nurses completed the majority of the consultation.

I feel that when … a nurse is involved, or someone else ... I’m … like a secondary person … If they spent 45 minutes with … the nurse, and then they spend a couple minutes with me, then I don’t feel as engaged ... as I would if I did the whole consult myself … [because] all that communication is lost, and ... [it] ends up being…a piece of paper that you’re talking ... from, or talking from the … computer. (HGP03)

GPs identified that interprofessional communication largely determined whether multiple providers’ involvement supported WPC. One believed that care would not change without physically co-located services.

… [I]f the … allied health services are located off-site and it’s still communicating … electronically … I think the care will be the same. (GP12)

Another believed ‘team-based care’ was not the best descriptor because of healthcare professionals’ relative independence of practice.

Multidimensional care

Some participants anticipated that HCHs would encourage attention to chronic disease management and social determinants of health, consistent with the scope of WPC.

… [S]ometimes those acute problems or other family member problems take precedence [over] … chronic ones, but it’s nice to have something in the background, monitoring and reminding people how to get the best outcomes ... (GP13)

… [I]n some ways, the HCH trial, or the … PCMHs … initiatives are helping us to look at the social determinants of health. (GP05)

2. Elements of the government’s Health Care Homes model impede whole‑person care

Both HCH and non-HCH participants had reservations about the government’s HCH trial.

I just don’t think the current model is one that works. (GP09)

[The government] say[s] all the right things beforehand … But when you look at what they’re actually doing … it’s very disappointing … they do not get it … and they won’t listen. (GP05)

GPs’ concerns relating to WPC included the trial’s limited scope fragmenting care, and capitation funding.

Health Care Homes’ limited scope fragments care

Several non-HCH participants believed that limiting HCHs to chronic disease management fragmented care, thereby impeding WPC.

… [HCHs will] be a disaster [for WPC] … because you can’t chop the patient into acute and chronic bits … the patient is a whole … W-H-O-L-E. (GP01)

… [An] HCH is for WPC [across the life course] … whereas the way the federal government has structured their trial, it’s only for people with … multiple comorbidities that are … a breath away from being hospitalised. So it’s just a really small component … (GP05)

Limitations of capitation funding

GPs had concerns about the impact of capitation funding on WPC, as spending time with patients facilitated WPC. Some felt that capitation funding discouraged this. One described being appalled at completing an HCHs training module promoting increased patient turnover.

… [W]ith HCHs … [the GP] could now see 44 patients in three hours … that’s four minutes per patient … If that’s what HCHs is trying to do … I think that’s … not good care. (HGP03)

Non-HCH participants identified the potential to ‘game’ (manipulate) the capitation funding system.

What’s gonna happen in the HCHs industry game with the three tiers? People are going to be hunting for diagnoses to maximise … the [top] tier. (GP01)

The only [way] it would work … from that kind of funding model would be, you try and accumulate … chronic disease patients, and then … see them as minimally as possible … because the more they come … the less … the clinic makes. So … there’s a disincentive to want to see the patient. (GP06)

Conversely, another HCH participant believed the model may enable flexibility for GPs to spend longer with patients (eg through home visitation).

One GP believed ‘gaming’ was already occurring in the HCH trial, though another reflected this was not unique to HCHs.

… [B]oth systems can be rorted; both systems can be manipulated. (cHGP01)

Additionally, non-HCH GPs were concerned that capitation funding did not reflect varying time requirements to manage the same disease in different patients.

… [C]hronic disease is not … one size fits all … some people are very motivated, and I don’t need to see them very often … [However], there are patients who are really, really sick and I do need to spend heaps of time with them. I don’t feel that I’m financially justified … getting … one payment for different severit[ies]. (GP04)

One GP was concerned that if performance targets were introduced, this would encourage a biomedical focus and detract from WPC.

3. Practical struggles relating to Health Care Homes

GPs expressed unsolicited views regarding practical difficulties with the HCH trial, and two withdrew from the trial for this reason.

I … love the theory behind it … but us trying to do it is an administrative nightmare ... (wHGP02)

[GPs] just weren’t interested [in participating] … it was going to be far too difficult … and potentially not financially rewarding to … pursue an HCH model. (wHGP01)

HCH and non-HCH participants expressed concerns about practical challenges; this was more pronounced among the former, whose experience reinforced these concerns.

Inadequate funding

Multiple GPs viewed HCHs as primarily a ‘cost-cutting exercise’ (HGP03, GP06).

I don’t think anyone honestly is going to say that … it’s an improved model of care for the patients. It’s … a funding mechanism. (cHGP01)

Many were concerned that it was inadequately funded and would reduce profit.

… [T]o me [HCHs is] … something that potentially … sets the stage for … trying to do more and more with less and less. (GP09)

They identified that lack of additional allied health funding under the government’s trial limited its capacity to improve team-based care.

… [T]here’s no extra money [under HCHs], as I understand it … for allied health services … it didn’t go very far in enabling more of what we might think of as WPC to happen … we won’t really find out the potential just from that [government] trial, because it has been quite limited. (GP08)

Underfunding was one of the most consistent reasons non-HCH participants reported for not engaging in the trial. Two GPs who withdrew from HCHs identified financial aspects as influential in this decision. While one HCH participant believed HCHs would result in more funding, GPs who reported calculating the financial impact of adopting the model did not share this view.

Practice restructure

GPs believed that billing under HCHs would be a ‘nightmare’ (GP04, GP07). Both HCH and non-HCH participants anticipated difficulty fairly apportioning capitated payments between doctors providing services within one practice.

… [We were] … challenged by … how to … ensure that … appropriate payment is actually directed to the person who’s providing the service … We just didn’t see how it was going to be plausible. How it possibly could work … It was just … too hard. (wHGP01)

Differentiating between acute and chronic presentations for billing purposes was also challenging.

… [O]ur struggle … is what to be billed as ... HCH, and what is billed as acute … for example, if someone’s got … COPD … And … come in with pneumonia … is that billed as … acute, or ... HCH? (HGP03)

Another challenge was staff training requirements, compounded by staff turnover, which GPs felt the government did not understand.

… [T]he people in Canberra and other places … I don’t think they have any understanding of how long this stuff takes to do … and how expensive it is in staff time. (wHGP02)

This GP believed the HCHs model was more feasible in large practices.

Additional practice-related struggles included paperwork requirements and identifying HCH patients.

Technological issues

Technological issues were primarily reported by HCH participants, who cited incompatibility between HCH software and practice management software, and difficulty adjusting to new technology.

The outside software, it’s impossible to load onto the system … she doesn’t talk well with the … computer system … they try to attack each other, which is not very useful. (HGP02)

One HCH GP identified non-functionality of the shared health summary due to providers outside the practice lacking necessary technology and patients’ fears concerning electronic health records. They suggested:

… [W]e just need to come back to it in five years’ time when the government has worked out how this stuff is going to run smoothly. (wHGP02)

Discussion

Providing WPC is a fundamental tenet of general practice. It is important to understand how GPs believe the government’s HCHs will affect WPC. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first on-the-ground study regarding views of GPs involved in and observing the HCH trial. The participants described tension between benefits of the HCHs model itself and its current implementation in the government’s HCH trial. Participants identified aspects of HCHs that may support WPC, including flexibility, continuity, team approaches and breadth of care. However, GPs within and outside the government’s HCH trial reported that aspects of this trial, including fragmented care and funding limitations, could impede WPC. Practical concerns related to limited funding, practice restructure and technological difficulties. Table 3 summarises the anticipated impact of HCHs on the domains of WPC.

| Table 3. The anticipated impact of Health Care Homes on the domains of whole-person care |

| Dimension of WPC |

Anticipated impact of HCHs |

| Positive impacts |

Negative impacts |

| Multidimensional and integrated approach |

- Supports multidimensionality of care (encourages attention to chronic disease and social determinants of health)

|

- Distinguishes between acute and chronic care, thereby fragmenting rather than integrating care

|

| Importance of the doctor–patient relationship |

- Continuity of care supports doctor–patient relationship development

|

- Doctor–patient relationship may be compromised if capitation funding results in the GPs’ role becoming a ‘paperwork exercise’, or spending less time with patients

|

| Recognises the individual personhood of each patient |

- Flexible care delivery supports individualisation of care

|

|

| Employs a range of treatment modalities |

|

- Limited by lack of additional allied health funding

- Limited by absence of service co-location

- Participants did not mention increased primary–secondary care continuity as a benefit of HCHs, despite this being an aim of the model1

|

| Acknowledges humanity of the doctor |

|

- Not identified by participants as being affected by HCHs; however, it is feasible that the practical struggles with HCHs that GPs anticipated may impact doctors’ wellbeing

|

| Views health as more than absence of disease |

- Not identified by participants as being affected by HCHs; however, if HCHs increase attention to preventive healthcare, they may support this dimension

|

|

| GP, general practitioner; HCH, Health Care Homes; WPC, whole-person care |

There were variable impacts of HCHs on the doctor–patient relationship underlying WPC. Participants identified HCHs’ potential to encourage continuity of care, a view supported by evidence from Patient-Centred Medical Home (PCMH) implementation in the USA.12–14 While patients believe continuity improves the doctor–patient relationship,15,16 the participants identified that building relationships requires time, which may be compromised by funding shifting care delivery away from the GP. Some GPs anticipated benefit from patients developing relationships with other care providers, provided there was effective communication among a GP-led team. However, one HCH GP felt that their role became a ‘paperwork exercise’, consigned to the role of signing off on the consultation conducted by a nurse. Evidence regarding PCMH patients’ experience in relation to patient–provider and patient–practice relationships in the USA is mixed, and this issue deserves further consideration.14

The participants reported practical struggles associated with HCH implementation. Previous literature anticipated difficulties concerning the transformation process, electronic health records, funding, and practice structure and resources.17 Participants did not report concerns about inadequate performance measures, with some GPs conversely adamant that performance targets would impede WPC.

The findings suggest that The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) and Australian Medical Association’s (AMA’s) positions on HCHs reflect GPs’ views. These organisations support the HCH model18–20 but view the government’s trial as ‘primarily … a cost cutting exercise’:21 ‘not a trial of a HCH [but] … a trial of a capitated funding model for chronic disease’.22 They shared the participants’ concerns regarding differentiating acute from chronic care, particularly where a consultation addresses both, and distributing practice payments.23 The AMA raised an additional concern regarding patient privacy with a shared health record.

No HCH participants reported more than 30 years’ practice. If this reflects the broader HCH GP demographic, it may represent changing perceptions of general practice over time or a reticence among GPs nearing retirement to implement a new model.

Stakeholders involved in Australian primary health reform should carefully consider these findings. They clarify features of HCHs that GPs believe will facilitate WPC, but highlight concerns with the current trial. Whether these can be adequately addressed remains unclear. It would be beneficial to differentiate between concerns related to the trial’s scope and funding, and those related to practical implementation difficulties.

Concerns related to the former require serious reconsideration of the trial model itself. This might include modifying capitation funding to reflect the time spent with individual patients over the preceding funding period. This may reduce the potential to ‘game the system’ and the disincentive to spend time with patients under a capitation model. It would provide fairer remuneration to care for patients who have the same chronic condition/s but require different intensities of care. Changes may also include widening HCHs’ scope by making all patients eligible to enrol, and increasing allied health funding to support team-based care.

Concerns related to practical implementation difficulties require targeted solutions to support implementation. The underfunding that the participants emphasised requires addressing. Other practical issues include: better integration of HCH software with practice management software, guidance on apportioning payments between attending doctors, and specific information about how current patient care could be improved under the model. This would require greater government consultation with the general practice profession.

Strengths of this study include reasonable demographic representation, with participants from HCHs and non-participating practices. GPs were included from six Australian states and territories. However, most non-HCH participants were located in urban Queensland; it is uncertain whether their views are transferrable to GPs in other locations, though no obvious state-based differences were observed within the sample as a whole. Selection bias is possible, as GPs with strong views on WPC or HCHs may have chosen to participate. The study focused on a single time point; future research tracing the evolution of GPs’ perspectives would provide further insight. Theoretical saturation was reached concerning the relationship between HCHs and WPC, but not GPs’ unsolicited views regarding practical struggles with the model (this was not the study aim); this study could act as a pilot for future research on this theme. Quantitative research could explore the representativeness of these findings; however, they provide valuable information in their own right. Finally, this study only sought GPs’ views. Future research should elicit other stakeholders’ (particularly patients’) perspectives.

Conclusion

The Australian GPs who participated in this study believed that the principles underlying HCHs may support WPC, but were concerned that these are not adequately encapsulated in the government’s HCH trial, and that aspects of this trial impede WPC. They identified significant practical challenges with the trial. Stakeholders planning the ongoing direction of Australian primary care should carefully consider these findings to support effective and sustainable provision of quality WPC.

Implications for general practice

- HCHs are likely to affect provision of WPC.

- HCHs may promote continuity, flexibility and breadth of care, and team-based care.

- GPs’ concerns regarding the scope, funding and practical feasibility of the government’s HCHs trial require attention to support quality WPC.