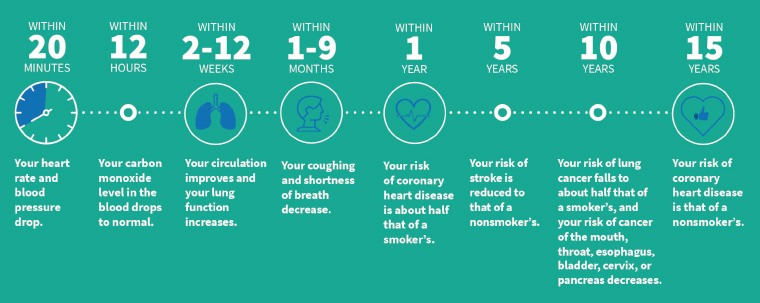

Australia has been a global leader in tobacco control and has one of the lowest rates of daily smoking in the world (currently 12.2%).1 However, national targets to reduce daily smoking to <10% and to halve the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult daily smoking rate by 2018 were not achieved.2 Smoking rates remain high in key population groups including people with mental illness. Smoking still causes a higher burden of disease than any other behavioural risk factor; in 2015, nearly 21,000 deaths in Australia were attributable directly to tobacco smoking.3 Smoking in pregnancy has serious adverse effects both for the mother and the developing fetus. As shown in Figure 1, quitting smoking has remarkable and rapid health benefits.

Figure 1. The effects of quitting over time. Click here to enlarge

Reproduced with permission from Drope J, Schluger NW, editors, The tobacco atlas, 6th edn, Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies, 2018, p. 37. Copyright 2018 The American Cancer Society, Inc. Reprinted with permission from www.cancer.org

Primary care practitioners including general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses are familiar with the challenges in promoting and supporting smoking cessation. This article addresses the challenges from a patient and provider perspective, and provides the most up-to-date evidence-based solutions to support busy practitioners. Brief advice significantly increases cessation rates and is highly cost effective. The most effective approach is a combination of both behavioural support and smoking cessation pharmacotherapy.

For the publication Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals,4 on which this article is based, the Expert Advisory Group (EAG) reviewed the recommendations from the first edition and also posed new questions in the PICO (patient, intervention, comparator, outcome) format. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners commissioned the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and the JBI Adelaide GRADE Centre to conduct evidence reviews on these questions, which resulted in Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) ‘Summary of findings’ tables. These tables were incorporated into an ‘evidence to decision’ framework, which the EAG used to move from the evidence to making practice recommendations. All recommendations received a GRADE rating on the quality of the evidence (certainty) and the strength of recommendation.5 Recommendations arising from the new PICO questions are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1. New pharmacotherapy recommendations |

Combination nicotine replacement therapy

Combination nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; ie patch and oral form) accompanied by behavioural support is more effective than NRT monotherapy accompanied by behavioural support, and should be recommended to people who smoke who have evidence of nicotine dependence.

Strong recommendation for intervention, moderate certainty |

Longer duration nicotine replacement therapy

For people who have stopped smoking at the end of a standard course of NRT, clinicians may consider recommending an additional course of NRT to reduce relapse.

Conditional recommendation for intervention, low certainty |

Nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy

For women who are pregnant and unable to quit smoking with behavioural support alone, clinicians might recommend NRT, compared with no NRT. Behavioural support and monitoring should also be provided.

Conditional recommendation for intervention, low certainty |

Longer duration varenicline

For people who have abstained from smoking after a standard course of varenicline in combination with behavioural support, clinicians may consider a further course of varenicline to reduce relapse.

Conditional recommendation for intervention, low certainty |

Concurrent use of varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy

For people who are attempting to quit smoking using varenicline accompanied by behavioural support, clinicians might recommend the use of varenicline in combination with NRT, compared with varenicline alone.

Conditional recommendation for intervention, moderate certainty |

Nicotine-containing e-cigarettes for smoking cessation

Nicotine-containing e-cigarettes are not first-line treatments for smoking cessation. The strongest evidence base for efficacy and safety is for currently approved pharmacological therapies combined with behavioural support. The lack of approved nicotine-containing e-cigarettes products creates an uncertain environment for patients and clinicians, as the constituents of the vapour produced have not been tested and standardised. However, for people who have tried to achieve smoking cessation with approved pharmacotherapies but failed, but who are still motivated to quit smoking and have brought up e-cigarette usage with their healthcare practitioner, nicotine-containing e-cigarettes may be a reasonable intervention to recommend. This needs to be preceded by an evidence-informed shared decision-making process, whereby the patient is aware of the following:

- no tested and approved e-cigarette products are available

- the long-term health effects of vaping are unknown

- possession of nicotine-containing e-liquid without a prescription is illegal

- in order to maximise possible benefit and minimise risk of harms, only short-term use should be recommended

- dual use (ie with continued tobacco smoking) needs to be avoided.

Conditional recommendation for intervention, low certainty |

| Reproduced with permission from The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals, 2nd edn, East Melbourne, Vic, RACGP, 2019, p. 7–8. |

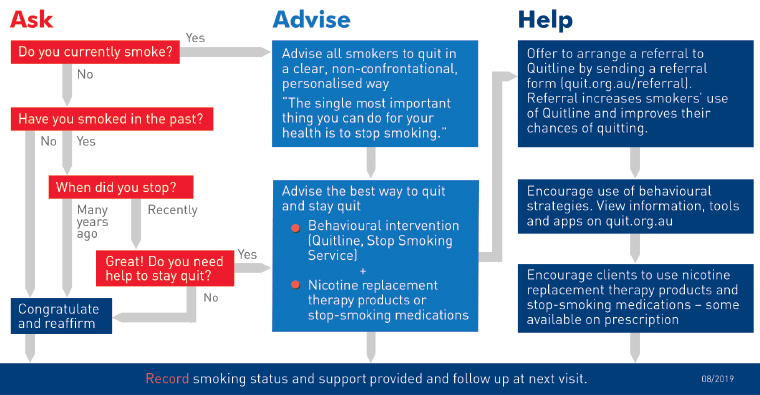

Brief intervention: Ask, Advise, Help

One of the barriers mostly frequently cited by health professionals to offering smoking cessation advice is the time required.6 When time is short, an option is the three-step Ask, Advise, Help structure developed by Quit Victoria. This brief intervention model (Figure 2) can be summarised as:

- Ask and record smoking status

- Advise all people who smoke to quit and inform them of the most effective methods

- Help by offering to arrange referral and encouraging use of behavioural intervention and use of evidence-based smoking cessation pharmacotherapy.

Figure 2. Three-step brief advice: Ask, Advise, Help. Click here to enlarge

Reproduced with permission from Quit Victoria, 3 step quit smoking brief advice – AAH model, Melbourne, DoH Quitline, 2018.

Behavioural intervention options include the Quitline (13 78 48) or a tobacco treatment specialist. The Quitline provides free telephone counselling and written resources. In most states, Quitline offers proactive support where a counsellor will telephone the person leading up to and after their nominated quit day and also provide feedback to referring health professionals. Quitline websites also provide a range of resources for groups with specific needs, including people with low literacy. The Australian Professional Society for Alcohol and other Drugs (APSAD) has a smoking cessation special interest group. Members of this group have training as tobacco treatment specialists and can offer in-person quitting support. GPs can email using the link on the APSAD website to identify a member of the group (www.apsad.org.au).

Comprehensive intervention: The 5As approach

If the practice has the capacity to offer comprehensive support for cessation, then the 5As approach (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, Arrange) provides a structure. It involves:

- Ask – enquire about and document the smoking status of all patients.

- Assess – evaluate nicotine dependence and assess and address barriers to quitting.

- Advise – counsel all patients who smoke to quit in a way that is clear but not confrontational.

- Assist – offer assistance in quitting, agree on a quit plan and recommend pharmacotherapy if the patient is nicotine dependent. If the patient is not willing to quit, use a motivational approach, explore barriers and review at future visits.

- Arrange – for patients making a quit attempt, arrange follow-up contact starting within a week of the quit day. At these visits, congratulate and encourage the patient, review progress and problems, encourage continued use of pharmacotherapy, and monitor and manage any medication side effects.

Barriers to quitting

Most long-term smokers would like to quit, and many have tried repeatedly to do so.7 There are often various beliefs and attitudes that are barriers to quitting, and it is important to try to identify and, where possible, offer advice or support to address these (Table 2). Support could include providing treatment for nicotine withdrawal symptoms or mental health issues, or recommending physical activity and a healthy diet to minimise weight gain.

| Table 2. Attitudes and barriers to quitting |

| Perceived barrier (mistaken beliefs and attitudes) |

Evidence-based strategies to address barriers33–35 |

- I can quit at any time

- I am not addicted

|

- Ask about previous attempts to quit and success rates

|

- Using cessation support is a sign of weakness

- Help is not necessary

|

- Reframe support

- Explain that nicotine withdrawal symptoms are reduced by treatment

- Highlight that unsupported quit rate is 3–5%, but substantially higher with assistance

|

- Too addicted

- Too hard to quit

- Fear of failure

|

- Ask about previous quit attempts

- Explore pharmacotherapy used and offer options (eg combination therapy)

|

- Too late to quit

- I might not benefit so why bother

|

- Benefits accrue at all ages, and are greater if cessation is achieved earlier: quitting at 30 years of age achieves similar life expectancy to those who do not smoke

- Provide evidence and feedback (eg spirometry, lung age, absolute risk score)

|

- My health has not been affected by smoking

- You have to die of something

- I know someone who smoked heavily who has lived a long time

|

- State evidence that one in two people who continue to smoke after middle age will die prematurely of smoking-related disease

- Reframe: for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) = smoker’s lung

|

- Not enough willpower

- No point in trying unless you want to

- To quit successfully, you really have to want to quit, then you will just do it

|

- Explore motivation and confidence

- Explore and encourage the use of effective strategies (eg Quitline, pharmacotherapy)

|

|

|

- Suggest other relaxation strategies such as breathing techniques and progressive muscle relaxation

|

|

|

- Average weight gain after smoking cessation is 2–4 kg; only about 10% of people have substantial weight gain (>13 kg)

- Suggest strategies to minimise weight gain: healthy diet; avoid high-fat and high-sugar foods and drinks; regular physical activity

- Point out that health benefits of quitting far exceed any adverse health effects of weight gain

|

|

|

- Suggest avoidance of high-risk social situations early in the quit attempt

- For some people it can be helpful to rehearse how to say no to a cigarette offer

|

| Reproduced with permission from The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals, 2nd edn, East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2019, p. 20. |

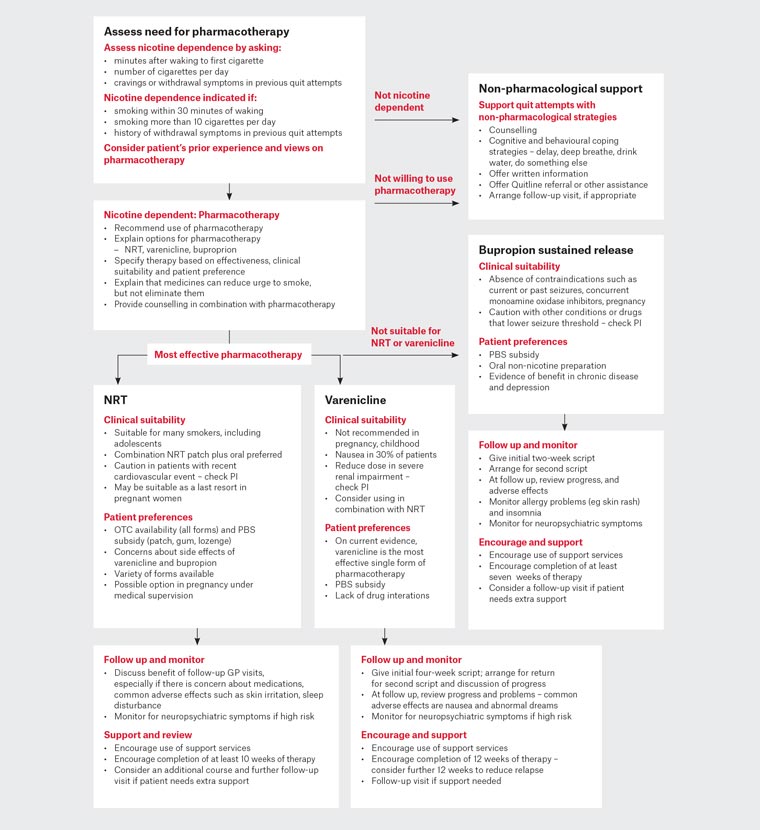

Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation

Pharmacotherapy can assist smoking cessation for people who are nicotine dependent. First-line pharmacotherapy options are medicines for which there is high-level evidence of effectiveness and safety, in addition to being licensed in Australia for smoking cessation. The current options are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; various forms available), varenicline and sustained-release bupropion. Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that, when accompanied by brief counselling, varenicline or combination NRT (patch plus rapidly acting form) almost triples the odds of quitting when compared with placebo at six months’ follow up. Bupropion and NRT monotherapy, also accompanied by brief counselling, almost doubles the odds of quitting when compared with placebo at six months’ follow-up.8,9 Current evidence indicates that varenicline and combination NRT are equally effective and are more effective than NRT monotherapy or sustained-release bupropion. They are therefore the preferred forms of treatment for most patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pharmacotherapy treatment algorithm. Click here to enlarge

GP, general practitioner; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; OTC, over the counter; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; PI, product information

Reproduced with permission from The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals, 2nd edn, East Melbourne, Vic, RACGP, 2019, p. 34.

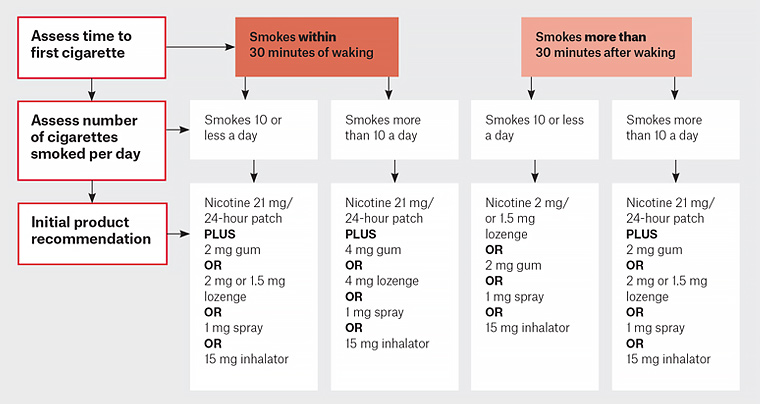

Nicotine replacement therapy

NRT is available in a long-acting form (nicotine patch) and in a variety of more rapidly acting oral forms (ie gum, lozenge, inhalator, mouth spray, oral strip). NRT monotherapy is modestly effective, increasing 6–12-month quit rates by 6% when compared with placebo.10 Combining a nicotine patch with faster-acting NRT increases 6–12-month abstinence rates by 5% over NRT monotherapy.10 It is important to advise patients on the correct use of the different forms of NRT to ensure an adequate dose is taken to relive cravings and withdrawal symptoms, and to encourage sufficient length of treatment. A guide to initial NRT dosing is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Nicotine replacement therapy initial dosage guideline. Click here to enlarge

Adapted with permission from Ministry of Health, New Zealand. Guide to prescribing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), Wellington, Ministry of Health, 2014. Available at www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/guide-to-prescribing-nicotine-replacement-therapy-nrtv2.pdf [Accessed 18 June 2020].

In one meta-analysis, pre-cessation treatment (starting two weeks before quit day) with nicotine patches has been found to increase success rates when compared with standard therapy.11 This approach has approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and is also subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Longer NRT treatment duration has been investigated in two randomised trials of longer treatment (up to 52 weeks) in comparison to standard course (8 weeks), but the studies found no convincing benefit.12 However, a systematic review of four trials conducted by JBI found evidence that longer term NRT can help reduce relapse in those who are abstinent at the end of a standard course or who have quit unassisted – see recommendations in Table 1.

An area of ongoing uncertainty has been the effectiveness and safety of NRT (and other smoking cessation medications) in pregnancy. For this reason, psychosocial intervention (eg counselling, feedback, financial incentives) are first-line treatment for women who are pregnant. Nicotine exposure in utero has been linked to harmful effects on the fetus in animal studies; however, in the small number of studies of NRT in humans, no adverse effects have been reported. An evidence review conducted by JBI examined studies that had measured the outcome of smoking cessation in later pregnancy.13 Eight RCTs involving 2199 participants met the entry criteria. The relative effect showed a small benefit in quit rates (risk ratio 1.41; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03, 1.93). The review found no evidence of an increase in adverse effects on the pregnancy or neonatal outcomes (miscarriage, stillbirth, pre-term birth, low birthweight, neonatal care unit admission, neonatal death) in women who used NRT during pregnancy. In fact, rates of all these adverse events were lower.

Varenicline

Varenicline is a partial agonist of nicotinic receptors in the central nervous system and acts to relieve cravings and withdrawal symptoms as well as reducing the rewarding effect of smoking. As previously stated, there is evidence that it is similar in effectiveness to combination NRT and is more effective than NRT monotherapy and bupropion. Behavioural support should always accompany treatment with varenicline. Nausea is a common adverse effect (affecting approximately 30% of users) but can be minimised by gradually up-titrating the dose and taking the medication with food. A systematic review conducted by JBI examined the evidence on longer term use of varenicline for the purpose of relapse prevention. Two trials involving 1297 participants were identified that met entry criteria.14,15 There was evidence of benefit, with a relative effect of 1.23 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.41; Table 1). There has been research on whether varenicline when co-administered with NRT is superior to varenicline alone, and JBI conducted a systematic review of the evidence on this question. Two trials meeting entry criteria were identified involving 787 participants.16,17 The relative effect was 1.62 (95% CI: 1.18, 2.23) with no evidence of increased adverse effects (Table 1). There has been concern about neuropsychiatric adverse effects with varenicline and its safety for people with severe mental illnesses; however, meta-analyses of RCTs,18,19 observational studies,20–22 and a large RCT including participants both with and without mental illness23 have not supported a causal link. Patients quitting smoking with any method are at some risk of increased psychological stress, especially those with a history of mental illness.

Bupropion

Originally developed as an antidepressant, bupropion in a lower dose sustained-release form significantly increases cessation rates when compared with placebo. The effect size is similar to NRT monotherapy.24 The combination of sustained-release bupropion with NRT has not been shown to increase effectiveness. The most common adverse effects are insomnia, dry mouth, nausea, dizziness and anxiety. There is a small risk of seizures, and bupropion is contraindicated for people with a history of seizure or eating disorders, and for those currently or recently taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

Second-line pharmacotherapy options

Second-line pharmacotherapy options are those for which there is evidence of benefit, but the medicines are not licensed in Australia for smoking cessation and there are known adverse effects or there is uncertainty about safety. These options would generally only be considered for people who have tried to achieve smoking cessation with approved pharmacotherapies but have not succeeded.

Nicotine containing e-cigarettes

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are battery-powered devices that deliver nicotine in a vapour without tobacco or smoke. The use of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes to support cessation is controversial. Their safety, particularly their long-term safety, is unknown. There are also concerns about concurrent use with tobacco, long-term use, and whether they promote nicotine use in non-smokers including young people. An outbreak in the USA of lung disease associated with e-cigarette use raised serious concerns about safety, but this was found to be due to use of vaping liquids containing cannabinoids.25 No application has yet been made to the TGA for approval of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes for therapeutic use in Australia. An evidence review conducted by JBI examined trials comparing nicotine-containing e-cigarettes versus NRT for biochemically validated smoking cessation. The review identified three randomised controlled trials with 1498 participants. The relative effect was 1.69 (95% CI: 1.26, 2.28).26–28 The follow-up in these studies ranged from eight weeks to 52 weeks. The EAG concluded that there is a moderate improvement in smoking cessation for nicotine-containing e-cigarettes when compared with NRT but rated the certainty of the evidence as low given the small number of studies (Table 1). The recommendation recognises the possible benefit of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes to help smokers who have tried repeatedly to quit without success, but it is important to note that that is not an endorsement of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes as a consumer product.

Nortriptyline

The tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline has been found in a small number of trials to significantly increase long-term cessation when compared with placebo.24 However, it is limited in its application by its potential side effects, including dry mouth, constipation, nausea, sedation and headaches, and a risk of arrhythmia in patients with cardiovascular disease. An overdose of nortriptyline can be dangerous, particularly in the elderly.

Groups with a high prevalence of smoking or special needs

Several population groups have either higher rates of smoking, greater risk of adverse effects or particular needs in terms of cessation support. Although there has been a fall in prevalence, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have daily smoking rates that are almost three times that of non-Indigenous Australians. Tobacco smoking accounts for approximately 23% of the health gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians.29 Reducing smoking is essential to closing the gap in health outcomes. Culturally appropriate smoking cessation services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities can be found at the Tackling Indigenous Smoking website (https://tacklingsmoking.org.au). The Closing the Gap PBS co-payment measure can reduce the cost of PBS-subsidised smoking cessation medications for Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander peoples with an existing chronic disease or those who are at risk of chronic disease. Further information is available at the PBS website (www.pbs.gov.au/info/publication/factsheets/closing-the-gap-pbs-co-payment-measure). Population surveys also indicate much higher smoking prevalence rates among those with mental disorders.30 Many people with mental health issues want to quit smoking but may require more intensive support and monitoring. This includes monitoring of doses of psychotropic medications, as liver metabolism of some drugs is affected by smoking. Smoking cessation is associated with reduced depression, anxiety and stress together with improved mood, compared with continuing to smoke.31 SANE Australia provides information for people with mental illness about smoking cessation on their website (www.sane.org/information-stories/facts-and-guides/smoking-and-mental-illness#guide). Other groups with particular needs are women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, young people, people in prison and people with smoking-related diseases including cardiovascular disease. Smoking cessation is vital for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD). A systematic review of 20 studies found a 36% relative decrease in mortality for patients with CHD who quit versus those who continued to smoke.32