Background

Chronic insomnia is a prevalent and debilitating disorder managed in Australian general practice. The most effective and recommended first-line treatment for insomnia is cognitive behavioural therapy. This treatment has been translated to a condensed brief behavioural therapy for insomnia (BBTi), which is suitable for delivery in the general practice setting. There is evidence that BBTi improves insomnia, daytime functioning and quality of life, with effects persisting far beyond treatment cessation. BBTi appears to be a cost-effective treatment that is superior to sedative–hypnotic management.

Chronic insomnia is characterised by difficulties initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, and/or early morning awakenings from sleep, with associated daytime impairments, persisting for at least three months.1 Chronic insomnia occurs in approximately 6–12% of the general population and commonly persists for many years unless targeted non-pharmacological treatments are provided.2–4 Insomnia results in significant economic costs to Australia through lost work productivity, increased healthcare utilisation, reduced quality of life, and increases risk of future depressive and anxiety disorders.5,6 Chronic insomnia is a costly and debilitating disorder, which requires targeted diagnostic and treatment approaches.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) guideline Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part B – Benzodiazepines recommends cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) as the first-line treatment.7 The core treatment components of CBTi include stimulus control therapy, bedtime restriction therapy, relaxation training, cognitive therapy and educational information about sleep.8 Because CBTi targets the underlying psychological, behavioural and physiological process and factors that underpin and perpetuate the disorder,7,9 improvements resulting from CBTi are sustained far beyond the cessation of therapy.10 Hence, cognitive and behavioural strategies to manage insomnia are preferable to sedative–hypnotic medications, which are associated with only short-term improvements and pose potential risk of medication dependence, tolerance and serious adverse events.7,11 CBTi has historically been delivered by trained psychologists or therapists over a course of six to eight individualised 30–50 minute sessions, but this is impractical for the Australian general practice setting. Furthermore, a lack of suitably trained healthcare providers in Australia who are capable of administering full CBTi programs has resulted in a greater need for effective evidence-based management of insomnia that can be provided in general practice.12

To encourage the adoption of CBTi techniques in primary healthcare settings, a ‘brief behavioural therapy for insomnia’ (BBTi) has been developed.13,14 BBTi distils the most essential and effective behavioural components of CBTi into a succinct four-session program. The RACGP benzodiazepine guideline supports the use of BBTi, which can be delivered by general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses with minimal training and without the need for costly overnight sleep studies.7,15 Despite the shorter duration, BBTi is effective in a diverse group of patients with insomnia, including in older adults,13 comorbid depression,16 hypnotic-resistant insomnia17 and individuals living with human immonodeficiency virus.18 Furthermore, BBTi assists patients in withdrawing from sedative–hypnotic medications, by improving sleep and reducing withdrawal/rebound insomnia symptoms.17 Importantly, several previous studies have shown the feasibility and efficacy of BBTi and other brief CBTi interventions in general practice settings,19,20 and when administered by practice nurses.14,20

Insomnia and depression/anxiety disorders commonly co-occur.21 Although acute depression/anxiety can initially cause sleep disturbance, insomnia symptoms can rapidly develop functional independence of these initial causes and persist for several months (eg chronic insomnia).22 It is recommended that even in the presence of stable comorbid mental health symptoms, insomnia symptoms require targeted diagnostic and treatment consideration.7 In fact, CBTi/BBTi techniques are effective in the presence of mood disorders,23 and commonly improve comorbid symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress.24

Contraindications to BBTi include seizure disorders, excessive daytime sleepiness (assessed as an Epworth sleepiness score >10),25 unstable psychiatric and/or medical conditions, and patients who spend less than six hours in bed.15 In cases where it is not possible or appropriate to administer BBTi in general practice, a GP may wish to refer a patient with insomnia to a psychologist for individualised CBTi with a mental health treatment plan (refer to Resources for GPs for access to psychologists experienced in sleep disorder management).

It is recommended that GPs consider managing insomnia with BBTi for the following reasons:

- Without treatment, insomnia commonly persists for many years.

- Sedative–hypnotic medications are the most common approach to insomnia management but they pose a risk of dependence, tolerance effects and serious adverse events to patients, and are less cost-effective over time when compared with CBTi/BBTi approaches.11,26,27

- BBTi assists patients in withdrawing from potentially harmful sedative–hypnotic medications.17,28

- Throughout BBTi, patients are taught how to self-manage future episodes of insomnia, resulting in sustained improvements in insomnia symptoms and a high probability of cost-effectiveness.

A step-by-step approach to brief behavioural treatment for insomnia

Several articles13,29–31 have provided a detailed description of BBTi justification, development, session-specific content and efficacy.

A step-by-step approach to administer BBTi within the Australian funding model is presented in Table 1. Although BBTi could potentially be delivered via a combination of GP and practice nurse appointments, GP-administered treatment sessions with practice nurse support may be more viable given the limited funding available for nursing consultations within the Medicare Benefits Schedule.20,32 Practice nurses can assist GPs to review information about a patient’s health history, insomnia symptoms and questionnaire and sleep-diary data; help to develop patient-centred goals for care; and provide education to patients. BBTi is suited to in-person and telephone appointments, and may be provided to individuals or in small-group settings.31

Although BBTi is traditionally delivered over four treatment sessions (one longer initial session, and three brief subsequent sessions), the first, longer session can be separated into two separate appointments, which may be more suitable for the time demands of Australian general practice.

| Table 1. Structure of brief behavioural therapy for insomnia in general practice |

| Session |

Brief behavioural therapy for insomnia approach |

Appointment time |

| Initial general practice appointment during which insomnia symptoms are identified |

- Identify patient with insomnia symptoms, potentially appropriate for BBTi

- Provide patient with a sleep diary, and questionnaires to complete before the next appointment (refer to Resources for GPs)

|

15 minutes |

| Assessment appointment – nurse assists GP to score questionnaires and sleep diary |

Enable a longer appointment to establish a diagnosis of insomnia1

- Score the sleep diary (example in Figure 2) and questionnaires

- Assess for comorbid psychiatric and medical symptoms/disorders

- Provide patient with insomnia materials (eg SA Health Insomnia Management Kit)

|

15 minutes |

| Session 1: Longer in‑person or telehealth appointment, one to two weeks later |

In the session:

- Provide information about sleep (eg normal sleep rhythm, assure patient that short nocturnal awakenings are completely normal) and healthy sleep practices (eg timing of meals, exercise and caffeine, sleep hygiene advice)

- Introduce the sleep drive (homeostatic) and biological factors that regulate sleep (Figure 1)41

The second half of the session should introduce treatment components:

- Introduce the four ‘rules’ to improve sleep (Box 1)

- Review diagnostic sleep diary to prescribe new bedtime ‘window’ (Figure 2); bedtime restriction is one of the most effective components of BBTi

- Discuss information and resources (refer to Resources for GPs) – patients should read and engage with these resources between sessions

- Provide enough sleep/wake diaries for the subsequent weeks

- Provide a longer first treatment session for patients with comorbid conditions/symptoms if needed

|

30–40 minutes |

| Session 2: Brief appointment, two weeks later |

The first opportunity to assess and titrate the new bedtime ‘window’ and provide motivational support to encourage engagement with treatment:

- Discuss the first two weeks of treatment, including patient’s feelings of sleepiness/fatigue, and any difficulties adhering to their new bedtime ‘window’

- Review sleep diaries to calculate average sleep and wake time

- Titrate bedtime ‘window’ according to 30/30 rule – if average wake time for the past week is >30 minutes, restrict the bedtime ‘window’ by another 30 minutes (but no less than six hours)

- If average wake time for the past week is <30 minutes increase bedtime ‘window’ by 30 minutes

- Teach patient the process for calculating average sleep/wake time from sleep diary and the 30/30 bedtime rule

- Schedule the next session in one to two weeks, and ensure patient has enough sleep/wake diaries

|

15 minutes, in‑person or telehealth appointment |

| Session 3: Brief appointment, one to two weeks later |

A brief adherence ‘booster’ session:

- Review average sleep and wake times from sleep diaries, and work with patient to titrate the bedtime ‘window’

- Prepare patient for self-management with the 30/30 rule, to prepare them for future relapse prevention

|

15 minutes, in‑person or telehealth appointment |

| Session 4: Brief appointment, one to two weeks later |

A brief adherence ‘booster’ session:

- Overcome barriers and titrate bedtime ‘window’

- Ensure patient is comfortable with the self-administration of bedtime restriction and stimulus control techniques, to continue managing any episodes of insomnia in the future

|

15 minutes, in‑person or telehealth appointment |

| Session 5 (optional session) |

An optional session for patients who require titration of bedtime parameters by a GP |

15 minutes |

| Review appointment three to six months after treatment |

- GPs may wish to book a review appointment three to six months after the patient has completed treatment

- Provide patient with a sleep diary and insomnia questionnaires one week before the appointment

|

15 minutes, in‑person or telehealth appointment |

| BBTi, brief behavioural therapy for insomnia; GP, general practitioner |

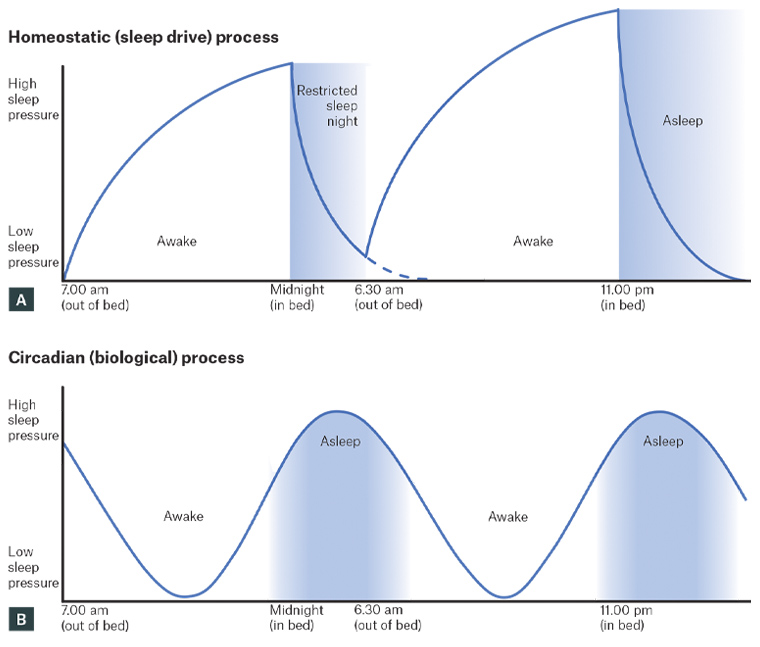

The four rules of BBTi

The core therapeutic components of BBTi are stimulus control therapy33 and bedtime restriction therapy.34 Both components rely on homeostatic (sleep drive) and circadian (biological) processes and have strong empirical support.10 To encourage engagement with therapy, it is essential that patients understand the rationale behind these treatment recommendations (refer to Figure 1 and Resources for GPs). The ‘homeostatic process’ refers to an increase in sleep pressure during each hour of wakefulness, and a reduction of sleep pressure during sleep (Figure 1A). Patients attempting to sleep when they have not acquired sufficient sleep pressure will find it difficult to fall asleep, or experience longer nocturnal awakenings. Alternatively, a patient who experiences a restricted sleep period on one night will experience greater sleep pressure, which will promote shorter wake-time during the subsequent night. The circadian process (Figure 1B) refers to natural changes in brain/biological rhythms lasting approximately 24 hours, which affect the optimal timing for sleep and wakefulness. Patients attempting to sleep at suboptimal periods of their ‘biological clock’ will find it difficult to initiate sleep, or experience a lighter and less refreshing sleep.

Figure 1. Homeostatic and circadian process of sleep regulation. Click here to enlarge

A. Homeostatic (sleep drive) process; B. Circadian (biological) process

The main therapeutic components of BBTi are combined into four simple ‘rules’ for better sleep (Box 1), which should be introduced during the first BBTi session.

| Box 1. The four ‘rules’ of brief behavioural therapy for insomnia |

1. Reduce your time in bed to consolidate sleep periods (bedtime restriction therapy)

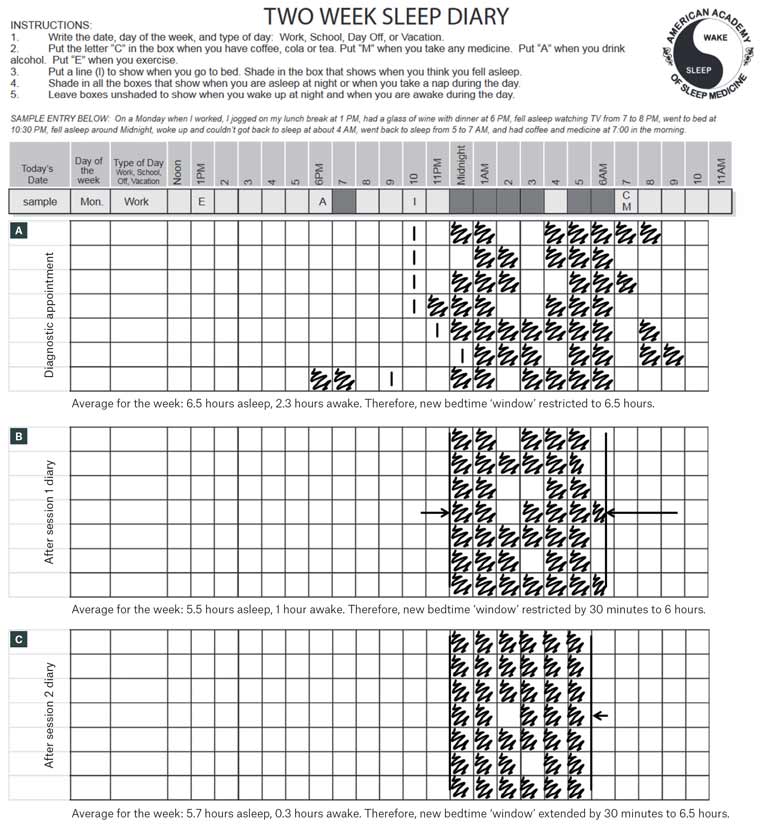

- Calculate the patient’s average weekly sleep time and wake time from their sleep diary (Figure 2).

- If average time awake is >30 minutes, restrict bedtime ‘window’ to match average sleep time (to no less than six hours). This should be a collaborative decision between patients and general practitioners, to set a bedtime ‘window’ that suits the patient’s lifestyle and body clock, to encourage adherence.

- Acknowledge and discuss the anticipated difficulties of multiple nights with the new restricted bedtime ‘window’ to set realistic expectations and ensure sufficient motivation for treatment.

- Discuss engaging in different activities in the evening to discourage going to bed too early.

- In the first one to two weeks of therapy, patients will be staying up later than usual. Ask them to nominate the activities that they will do during this time.

- Encourage patients to plan activities in the morning to incentivise getting out of bed at the recommended time.

- Warn patients of increased sleepiness during the initial one to two weeks of restriction therapy:42

- Frame this increased sleepiness as a positive indication that therapy is working.

- Advise patients to plan driving and work activities/duties accordingly if they are feeling excessively sleepy.

- Warn patients about falling asleep in front of the TV in the evenings, which will undermine the sleep pressure needed to fall asleep when they get into bed.

- Bedtime ‘windows’ should be modified from session to session, according to the patient’s average sleep and wake time from the previous week (Figure 2).

2. Get up at the same time of day every day of the week, no matter how poorly you slept the night before

- Regularise sleep/wake patterns to ‘re-set’ the biological clock each day, and ensure sufficient sleep pressure to promote sleep on the following night.

3. Do not go to bed unless sleepy

- This reduces the likelihood of lying in bed while awake.

- Assist patient in distinguishing sleepiness (likelihood of falling asleep) from fatigue (mental or physical weariness/exhaustion).

4. Do not stay in bed if you do not fall asleep quickly (stimulus control therapy)

- If not asleep within approximately 15 minutes (quarter-hour rule), the patient should get out of bed and go to another room until they feel sleepy. This can be repeated as many times as necessary throughout the night. This helps to overcome the ‘conditioned’ insomnia response.

- Encourage relaxing activities (reading, music, crossword puzzles), rather than arousing or screen-time activities during these ‘out of bed’ periods.

|

Figure 2. Example sleep diaries during bedtime restriction. Click here to enlarge

A. Average time awake was initially >30 minutes. Therefore, the bedtime window was restricted to average sleep time (ie 6.5 hours); B. By session 2, average time awake remained >30 minutes, so the bedtime window was restricted by an additional 30 minutes; C. By session 3, average awake time was <30 minutes, so the bedtime window was increased by 30 minutes for the next week.

Patients taking sedative–hypnotic medications

GPs commonly manage patients with a history of long-term sedative–hypnotic medication use.26 BBTi is effective in the presence of sedative–hypnotic use,13,17 and BBTi techniques have been shown to improve sleep and gradually reduce dependence on sedative–hypnotic medications over time.17,35,36 It is thought that BBTi may reduce withdrawal/rebound symptoms during the withdrawal process, and thereby improve successful elimination of sedative–hypnotic use.17,28,35 The RACGP benzodiazepine guideline contains useful information and referral options about managing prescribing and gradual withdrawal of sedative–hypnotic medications.7

Role of practice nurses in BBTi

Practice nurses have great interest and potential to assist in the management of insomnia. Evidence indicates that practice nurses can provide effective non-medication insomnia management within the primary care setting, to relieve the burden on GPs while supporting the adoption of guideline recommendations.7,20,32 A recent Australian qualitative study also found that practice nurses are interested in becoming more involved in the management of sleep disorders in general practice (eg insomnia and sleep apnoea).37

Conclusion

Chronic insomnia is a common, debilitating and economically costly disorder managed in Australian general practice. Although cognitive and behavioural therapy for insomnia is an effective and durable treatment, it is poorly suited to the time constraints of general practice settings. BBTi distils the most effective behavioural treatment components into several brief in-person/telehealth sessions. As BBTi leads to insomnia improvements that are sustained far beyond the cessation of therapy, it is a cost-effective treatment for insomnia that is preferable to sedative–hypnotic medications.26

Resources for GPs

- SA Health – Sleep problems – Insomnia Management Kit

- Sleep diaries

- RACGP (HANDI) BBTi information

- If BBTi is not suitable, a mental health treatment plan can be used to refer patients to a psychologist for cognitive and behavioural therapy for insomnia; GPs can use the Australian Psychology Society’s ‘Find a Psychologist’ tool to find a local psychologist specialising in insomnia treatment, searching by issues, general health, sleeping disorders, www.psychology.org.au/Find-a-Psychologist

- The RACGP guideline Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, – Part B: Benzodiazepines contains useful CBTi information/handouts (pages 72–73)7

- Recent articles13,29–31 include session-by-session information on BBTi

- Multiple standardised questionnaires may be used to measure sleep,38 insomnia symptoms,39 daytime sleepiness,25 and depressive symptoms40 in general practice