Australia allocates approximately 14,000 places through Australia’s Refugee and Humanitarian Program per year for people overseas seeking refuge or asylum; of these, fewer than 3000 are permanent protection visas.1,2 In addition, there are thousands of people seeking asylum living in the community. For this newly arrived population in Australia, primary healthcare practitioners (PHPs) are usually the first point of care, with many of these patients experiencing complex health needs.3,4 During a medical encounter, communication and the doctor’s interpersonal skills both play a key part in patient satisfaction, compliance and positive health outcomes.5,6 Doctor–patient communication is emphasised as an important skill in medicine, medical education and standards for professional practice.7,8 Aspects of communication are highlighted through all seven domains of one competency framework for Australian clinicians working with people from migrant and refugee backgrounds.9

The communication behaviours exhibited during the doctor–patient interaction are strongly associated with patient satisfaction during a consultation; however, the additional challenges of navigating linguistic and cultural factors can make communication difficult to achieve with patients from refugee backgrounds.10–12 Communication is paramount in building confidence and trust between the doctor and patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.13 When looking at the doctor–patient relationship for this population group, both spoken and written language barriers are a common issue.4,14 Even with the help of professional interpreter services, there are problems with availability and concerns among patients about the confidentiality and accuracy of the interpreters.4 In Australia, general practices have access to and routinely use the free telephone interpreter service. Onsite interpreter services, which usually require pre-booking, are not routinely used in Australian general practice.3 When using an interpreter, concerns about confidentiality may arise from patients from a language background where the interpreting pool is limited, and therefore the interpreter could be someone they know or someone close to them.

A literature review of healthcare practitioner and refugee and asylum seeker patient experiences of communication during consultations found that alongside language barriers, cultural factors and cues from the healthcare practitioner, such as hand gestures and listening to non–medically relevant information, are also influential in shaping the overall patient experience and degree of satisfaction.15 Trauma-informed care, which highlights awareness and sensitivity to a person’s experiences, is relevant to this population group, as they have additional experiences of displacement and trauma.16 Additionally, the demonstration of compassionate care from the healthcare practitioner is important in building trust and improving the healthcare practitioner–patient relationship.17

Multiple resources have been produced to support communication between PHPs and their patients from refugee and asylum seekers backgrounds, which includes people who have fled their country of origin as a result of persecution, conflict, violence and human rights violation.18 In Australia, these resources have been developed by a range of organisations at the local and national level. However, it can be difficult for PHPs to efficiently identify and find trusted, comprehensive and user-friendly resources. To date, there have been no systematic efforts to identify, appraise and synthesise resources available to PHPs to guide their communication skills with this population group.

The aim of this environmental scan was to systematically identify, appraise and synthesise good-quality online resources available to Australian PHPs to support communication with refugee and asylum seeker patients. In this article, PHPs refers to specialist general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses.

Methods

The study consisted of two components: 1) a systematic environmental scan to identify resources aimed at improving healthcare communication and 2) an assessment of the content, purpose, actionability and understandability of identified resources.

Resources of interest were grey literature consisting of guidelines, practice standards, health information materials/leaflets/posters, written communication advice for PHPs and PHP education materials.

Environmental scan

The internet has rapidly become a useful tool to disseminate medical research evidence and guidance, especially by government departments and key health organisations.19 Environmental scan processes provide a snapshot of the availability of online resources at a given time point and have previously been used to assess available patient resources in the context of general practice.20,21 An environmental scan of the internet and grey literature using the Google search engine was therefore identified as an appropriate search methodology.

Inclusion criteria

Resources were included in the evaluation if they met the following criteria: 1) included information on communicating in consultations specifically with refugees and asylum seekers, 2) targeted PHPs and were 3) Australian (ie through URL domain extension or organisation name), 4) publicly accessible and 5) written in English.

Exclusion criteria

Resources were excluded in the evaluation for the following criteria: 1) paid material (requiring payment, registration, log in or software downloads), 2) targeted at consumers or 3) required following more than two links from the search result.20,21

Search strategy

Strategy 1

A list of established Australian practitioner organisation websites known to the research team were screened for communication resources (Box 1). This involved systematic searching and screening for resources relevant to the area of interest within each website using search terms listed in Box 1.

| Box 1. Search strategy |

| Australian organisations identified by the research team |

|

|

| Systematic Google search: Search terms created by grouping a term from each column with ‘AND’ |

- Communication

- Interaction

- Engage

- Trauma

- Person-centred

- ‘Social history’

|

- ‘Health care’

- ‘General practice’

- Clinician

- Physician

- Doctor

- Nurse

|

- Refugee*

- ‘Asylum seeker*’

|

Strategy 2

The second search strategy involved conducting a systematic internet search using Google Australia with English-language terms. Search terms were developed to reflect the terms found in scientific literature when aiming to look at communication experiences of healthcare providers and patients from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds (Box 1). In addition to search terms found in scientific literature, additional terms were developed collaboratively by researchers with clinical backgrounds (MT and LT).

Screening process

A total of 72 unique searches were conducted in March 2020 by one independent reviewer (PP). Prior to each of the 72 searches, the cache in the web browser settings was cleared and reset to minimise the influence of Google’s search optimisation function. Each search term was entered, and the first 100 results, excluding advertisements, were downloaded to an Excel spreadsheet. The 7200 results were then screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers (PP and MP). The discrepancies were resolved by a third independent reviewer (MT) who is a GP researcher. Webpages were treated as separate resources if they contained individual content and URLs.

Where there were duplications of resources on different webpages, such as different organisations uploading the same practice guidelines (identical content), these additional webpages were removed as duplicates to ascertain the final number of unique resources.

Data extraction and evaluation

The Silberg criteria22 outline the benchmark for internet-based medical information to be based on four criteria: authorship, attribution, disclosure and currency. Data including the website URL, name of the author or author organisation, date of creation or last update and the presence of any references to published peer-reviewed literature were extracted and recorded in an Excel spreadsheet by the two screeners (PP and MP). Additionally, the resource aims were extracted by the screeners.

The content of each of the resources was rated, by one independent rater, using a validated tool for printed patient education materials, the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printed Materials (PEMAT-P).23 The PEMAT-P was developed by experts in the field, has been used to evaluate consumer-based health resources and is available widely.23 It contains two domains: 1) understandability, which is a measure of how well the reader is able to process and explain the key message, where higher percentages indicate better understandability; and 2) actionability, which is a measure of how well a person is able to identify what to do on the basis of the information presented, where higher percentages indicate better actionability. To adapt for PHP resources, item 4 in the PEMAT-P tool, which refers to the use of medical terms with definitions, was excluded in the evaluation.

Taxonomy of purposes

Previous research by Willis et al24 and Lowe et al25,26 developed and validated a taxonomy of purposes and definitions for communication interventions that classifies interventions into seven types: inform or educate, remind or recall, teach skills, provide support, facilitate decision making, enable communication, and enhance community ownership. The use of such a taxonomy allowed for the resources to be treated as an intervention and assisted with the identification of the aim and purpose of each resource. Definitions for each category can be found in Appendix 1.

Using the taxonomy of purposes, all relevant categories were assigned to each of the resources by PP and MT, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion. If more than one category could be applied to the resource, all applicable were documented.

Content analysis

In addition, the researchers deductively coded the content of the resources to key concepts of communication. The coding was performed with categories derived from themes in the literature review, which looked at both qualitative and quantitative studies reporting on communication experiences of PHPs and people from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds.15 Thematic analysis of those studies highlighted three key themes: linguistic barriers, clinician cues and cultural understanding. These categories were evidence based and were shown to be important factors in communication with refugees and asylum seekers. The coding scheme and categories were revised through an iterative process of discussion involving MT and PP and reflection of the 3C Model, which summarises the key challenges in healthcare delivery for refugees and migrants.13

Furthermore, the researchers looked at identifying what proportion of the overall content in the resource was relevant to communication. Within the content relevant to communication, this was further broken down into the four communication categories developed (Appendix 2).

Results

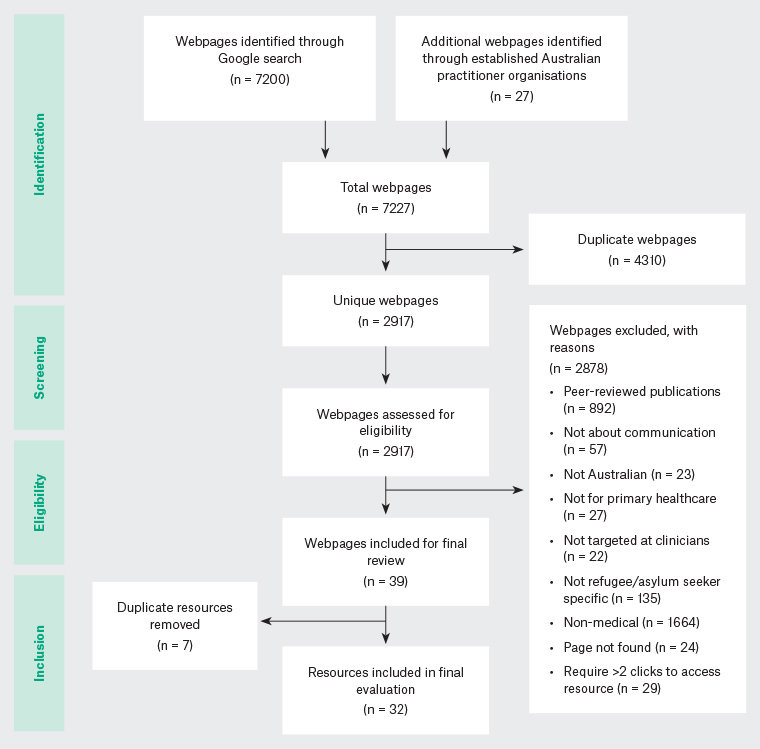

A total of 7200 webpages identified through the Google searches were considered for eligibility, and an additional 27 webpages were identified from searching the established Australian practitioner organisation websites. After the eligibility and screening process, 32 resources were identified for evaluation. An overview of the study search strategy and results is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of search strategy and results

For the included resources, the length ranged from one page to over 200 pages in a single resource. The target audience for the resources fell into four categories: PHPs (50.0%); GPs (18.8%); nurses

and/or midwives (21.9%) and clinicians in general (9.4%). The included resources all had clearly identified authors/author organisations, and 94% of them had the date of creation/last update clearly stated on the resource, ranging from 2013 to the date of preliminary review, 19 March 2020. From the included resources, 22 of the 32 (69%) clearly referenced peer-reviewed literature in their reference list. Appendix 3 shows the resource descriptions for all 32 of the identified results.

Resources scored between 45% and 87% in the understandability domains of the PEMAT-P, and between 0% and 80% in the actionability domains. The identified resources were each assigned between two and five purpose taxonomy types, and the proportion was as follow: inform, educate, remind or recall (100%), enable communication (100%), teach skills (56.3%), provide support (25%), facilitate decision making (18.8%) and enhance community ownership (3.1%). Table 1 shows a sample of well-rated resources, capturing their diversity of formats and different suggested use in clinical practice. These resources rated well in the PEMAT-P appraisal, had multiple purpose taxonomy types and were developed by established Australian organisations.

| Table 1. Sample of the diversity of resources with descriptions and suggested uses, rated using the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printed Materials (PEMAT-P) |

| Resource |

Description and suggested uses |

Understandability (%) |

Actionability (%) |

Relevant content to communication (%) |

Purpose taxonomy /6 |

A. Communication and interpreters

Australian Refugee Health Practice Guide, 2020 |

A single-page summary of communication issues, tips and useful links – it is a section within the refugee practice guide, which has a suite of informative pages |

64 |

80 |

100 |

3

Inform/educate/remind; teach skills; enable communication |

B. Area for improvement: Communication

Victorian Refugee Health Network, 2016 |

A practical practice guide for implementing the structural needs of general practitioners to care for refugees and asylum seekers |

55 |

60 |

100 |

3

Inform/educate/remind; provide support; enable communication |

C. Caring for refugee patients in general practice

Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc., 2012 |

A desktop guide for overall guidance on refugee health, with hyperlinks to sections within the resource and to external resources for further information |

75 |

60 |

15 |

4

Inform/educate/remind; teach skills; facilitate decision making; enable communication |

D. Guide for clinicians working with interpreters in healthcare settings

Migrant and Refugee Women’s Health Partnership, 2019 |

An extensive guideline for working interpreters in clinical practice; a useful resource about practical considerations when using interpreters |

75 |

60 |

100 |

4

Inform/educate/remind; teach skills; facilitate decision making; enable communication |

E. Abuse and violence: Working with our patients in general practice (White Book) – Chapter 12: Migrant and refugee communities

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), 2014 |

A practical guideline that covers communication and culturally appropriate care and provides guidance on how to deliver trauma-informed care |

82 |

60 |

20 |

4

Inform/educate/remind; teach skills; provide support; enable communication |

Of the 32 resources included, only four had the sole purpose of being a communication resource for use with refugees and asylum seekers. Additionally, 21 of the resources contained 70% or more content unrelated to communication.

Through the inductive process, the researchers identified four factors affecting communication during consultations with refugees and asylum seekers: language barriers, PHP responsiveness to individual, continuity of care and cultural factors. Table 2 highlights the suggested approaches and considerations to address these factors, derived from the sample of well-rated resources in Table 1.

| Table 2. Summary of factors affecting communication during consultations with refugees and asylum seekers, informed by the resources that were well rated by the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printed Materials (PEMAT-P) |

| Factor |

Suggested approaches and considerations |

| Language barriers |

Ask the patient if they have a preferred language [A,C*] |

| Organise an interpreter through the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) [A–E] |

| Continuity of care |

Build familiarity through multiple visits [A,C] |

| Where possible, try to organise the same interpreter to help build rapport and trust [A,C,D] |

| Primary healthcare practitioner’s (PHP’s) responsiveness to individual |

Engage the patient directly; that is, face the patient and speak directly to them, even when there is an interpreter [A,C,D,E] |

| Apply trauma-informed care, as some patients may have experiences of torture and traumatic events [A,C,E] |

| Emphasising PHP–patient confidentiality and explaining consent, choice and control [A–E] |

| Cultural considerations |

Be mindful of alternative health beliefs and religious practices [A–E] |

| Create a non-judgemental and supportive environment to allow patient to feel culturally safe [A,C,D,E] |

| Ask patients if they have a preference for gender concordance with their PHP and interpreter [A,C,D,E] |

| *Refers to resource letters in Table 1 |

Discussion

This work represents the first attempt to systematically identify and compare resources that have been designed to guide PHPs in communication with patients from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds. From the environmental scan, the researchers identified 32 unique resources available to Australian PHPs.

Resources with high ratings clearly identified the applicability to refugees and asylum seekers, had higher understandability and actionability scores, covered multiple purposes using the taxonomy (Appendix 1) and had content that addressed all four identified factors of communication: language barriers, continuity of care, PHP responsiveness to the individual and cultural considerations (Appendix 2). Additionally, these resources had information to help inform/remind the reader of key communication skills and suggestions to help them operationalise the knowledge.

Findings from this study also highlight that the overall content in resources available to Australian PHPs is quite varied in length, and the proportion of relevant information in most instances is quite small. PHPs using resources and tools to guide their communication would be required to, in some instances, scroll through multiple pages to find the relevant information. Resources that rated highly overcame this obstacle by containing informative headings and hyperlinks that allowed for ease of navigation and easier searchability of key information. The quality of the content of the included resources can, in part, be evaluated by citation of references, including peer-reviewed literature.27 Only approximately two-thirds of the 32 resources included reference lists to substantiate the information, and only a couple mentioned consumer involvement in the development of the resources. Consumer involvement in research is considered best practice;28 of the included resources, only two of the resources (resources 15 and 31 in Appendix 3) had consumer involvement explicitly stated in the resource. Refugees and asylum seekers are some of the key stakeholders in this interaction, and their input and contribution to clinician resources should be considered when developing future resources

Literature regarding healthcare practitioner information-seeking behaviours reveals lack of time and lack of search skills as barriers to information searching.29 Finding resources could be challenging for time-poor PHPs, as specific search terms are required and can, at times, be within lengthy documents. While many of the resources have similar content albeit with varying levels of detail, this environmental scan highlights that the different types of resources could have different roles in practice (Table 1). For example, a single-page summary from the Australian Refugee Health Practice Guide could be used as a brief reference or reminder and source of relevant links; in contrast, a resource such as The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ Abuse and violence – Working with our patients in general practice (White Book) can be used by PHPs who want an in-depth resource for learning or continuing professional development.

The purpose of many of the resources was to inform, remind or recall; however, it is uncertain whether the resources alone allow PHPs to operationalise the knowledge. Research shows that evidence-based communication skills training, in particular, is more useful than methods that encourage thinking about communication skills.30 Communication skills are an ongoing learning process, and many PHPs learn on the job.30 Further efforts should be made to develop evidence-based communication skills training. Development of the training could be based on the well-rated resources found in this environmental scan, while taking into account the additional considerations needed when the patients are from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds, including the need for trauma-informed care.

The identified factors affecting communication in consultations were language barriers, PHP–patient interpersonal relationship, continuity of care and cultural considerations. It was apparent in the identified resources that building trust and rapport led to improved communication. Other factors, such as body language and the PHP being receptive to cues from the patient, illustrate many of the resources are consistent with learning from literature.31 While there are additional cultural and practical (ie interpreter use) considerations during consultations with refugees and asylum seekers, the overarching communication skills required by the PHP would be relevant to most patient groups.7

A strength of the environmental scan methodology was that it allowed all resources available to Australian PHPs online to be collated and assessed using a widely used search engine in Australia.32 The use of two independent screeners and an additional third expert screener was another strength, as it decreased the chance that relevant resources could have been missed and ensured rating scales were independently applied, strengthening the quality of the ratings.

A limitation of the study is that although the researchers followed a published methodology for the environmental scan, because of the dynamic and vast nature of information published on the internet, it is highly unlikely that the search results were exhaustive or complete.33,34 In addition, there could be additional resources designed to be used with those from multicultural backgrounds that might not have been included because of the specific search terms and inclusion criteria. While the researchers used some proxy measures, it is possible that using different search engines or time points would yield different search results. Additionally, to improve the reliability of the environmental scan, the search process would ideally have been conducted by at least two different searchers.21,33 Also, in the absence of an appraisal tool for healthcare practitioner education material, a patient education material assessment tool (PEMAT-P) was used to appraise the resources. While the domains of the PEMAT-P are relevant to similar materials, there are elements of materials designed for professionals that may have affected scores, potentially underrating or overrating the resources’ real-world useability.

Conclusion

Australian PHPs seeking resources to guide their interaction and communication with patients from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds have numerous options available to them. Of the 32 resources identified, these researchers have highlighted a sample of diverse resources well rated by the PEMAT-P (Table 1) and summarised the key messages (Table 2) to be referred to by individuals and practices providing care for refugees and asylum seekers. The resources cover four factors involved in improving communication: language barriers, continuity of care, PHPs’ responsiveness to the individual and cultural considerations. Additionally, research into what resources PHPs actually use and how they access these resources is warranted to understand the resources’ role in guiding PHP interactions with patients from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds.