An increasing number of patients will ask Australian general practitioners (GPs) to write nicotine prescriptions and counsel them about vaping under new Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) regulations that commenced on 1 October 2021. Patients require a prescription to purchase nicotine e-liquid from an Australian pharmacy or to import it legally from overseas.1

Vaping nicotine is positioned in Australia as a second-line treatment that may be appropriate for adult smokers when first-line quitting methods have not been successful.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) recognises a role for vaping for selected smokers.2 The 2021 guidelines state,

For people who have tried to achieve smoking cessation with first-line therapy (combination of behavioural support and TGA-approved pharmacotherapy) but failed and are still motivated to quit smoking, NVPs [nicotine vaping products] may be a reasonable intervention to recommend along with behavioural support. However, this needs to be preceded by an evidence-informed shared-decision making process, whereby the patient is aware of the following caveats:

- Due to the lack of available evidence, the long-term health effects of NVPs are unknown.

- NVPs are not registered therapeutic goods in Australia and therefore their safety, efficacy and quality have not been established.

- There is a lack of uniformity in vaping devices and NVPs, which increases the uncertainties associated with their use.

- To maximise possible benefit and minimise risk of harms, dual use should be avoided and long-term use should be minimised.

- It is important for the patient to return for regular review and monitoring.

Vaping is controversial in Australia, with authorities taking a ‘precautionary approach’ because of concerns such as youth uptake and unknown long-term health effects.3

This article focuses on vaping nicotine as a quitting aid and harm-reduction tool in general practice. It reviews the latest evidence for safety and effectiveness, outlines the devices and e-liquids available, and advises how to counsel smokers about vaping and how to write a nicotine prescription.

What is vaping?

Vaping involves heating a liquid nicotine solution (e-liquid, e-juice) into an aerosol, which is inhaled and exhaled as a visible mist. Vaping delivers nicotine and mimics the hand-to-mouth action and sensations of smoking.

Vaping nicotine is only appropriate for adult smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit smoking tobacco with first-line treatments. For some smokers it is a short-term quitting aid. For others it serves as a longer-term, less harmful substitute for smoking (tobacco harm reduction).

Risk when compared with smoking

Vaping nicotine is not risk-free and is not for non-smokers or those under 18 years of age. Vapour contains low doses of some toxic chemicals such as heavy metals, carbonyls and volatile organic compounds, and studies have found some harmful effects.4 Some non-smokers who vape become dependent on nicotine, and there is a rare risk of battery explosions.

When smokers switch to vaping, toxic ‘biomarkers’ are substantially reduced,5 and studies have shown improvements in blood pressure, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a reduced risk of ischaemic heart disease.6–9

Nicotine by itself does not cause cancer or lung disease and is not a cause of significant cardiovascular disease.10–12 It is a toxic poison in high doses and can cause serious harm if ingested.

Nicotine has been linked to harmful effects on the fetus in animal studies, although there is currently no evidence that these findings apply to humans.13 Nicotine may not be completely safe for the pregnant mother and fetus, but it is always safer than smoking.10

The long-term risk of vaping has not yet been established. The UK Royal College of Physicians has estimated that it is unlikely to be more than 5% of the risk of smoking, although this figure is contested.14

Is vaping an effective quitting aid?

There is a growing body of evidence that vaping can help smokers quit. Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) by the Cochrane group15 and a review commissioned by the RACGP16 concluded that vaping nicotine was 53–69% more effective than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). The certainty of the evidence was moderate15 and low16 respectively, and more studies are needed to confirm the exact effect size.

In absolute terms, out of 100 smokers trying to quit, six will succeed with NRT at six months, compared with nine or 10 using a vaping device.

No trials have directly compared vaping with varenicline or bupropion; however, a recent network meta-analysis of 171 RCTs by the UK National Institute for Health Research concluded that electronic cigarettes were more effective for smoking cessation than either medication.17

The findings from RCTs are consistent with observational and population studies and the accelerated decline in smoking rates in the US and UK after vaping became widely available.18–20

The role of the general practitioner

GPs can assess suitability for vaping, provide additional quitting support and can write a nicotine prescription if appropriate.2 Nicotine vaping products are unregistered, and the RACGP guidelines advise that it is reasonable not to prescribe them.

It is important to ask if the patient has tried approved quitting methods. Were they used correctly, and should a re-trial be considered? Is the patient nicotine dependent? Discussing the risks and benefits of vaping can help the patient make an informed decision.

GPs can advise on the concentration and safe use of nicotine liquid. New vapers can select their starting products with the help of vape shop staff and online resources.

Established vapers will have a preferred vaping device and e-liquid and generally only require a nicotine prescription. For these patients, the GP can advise the patient to quit vaping if possible and discuss safety issues.

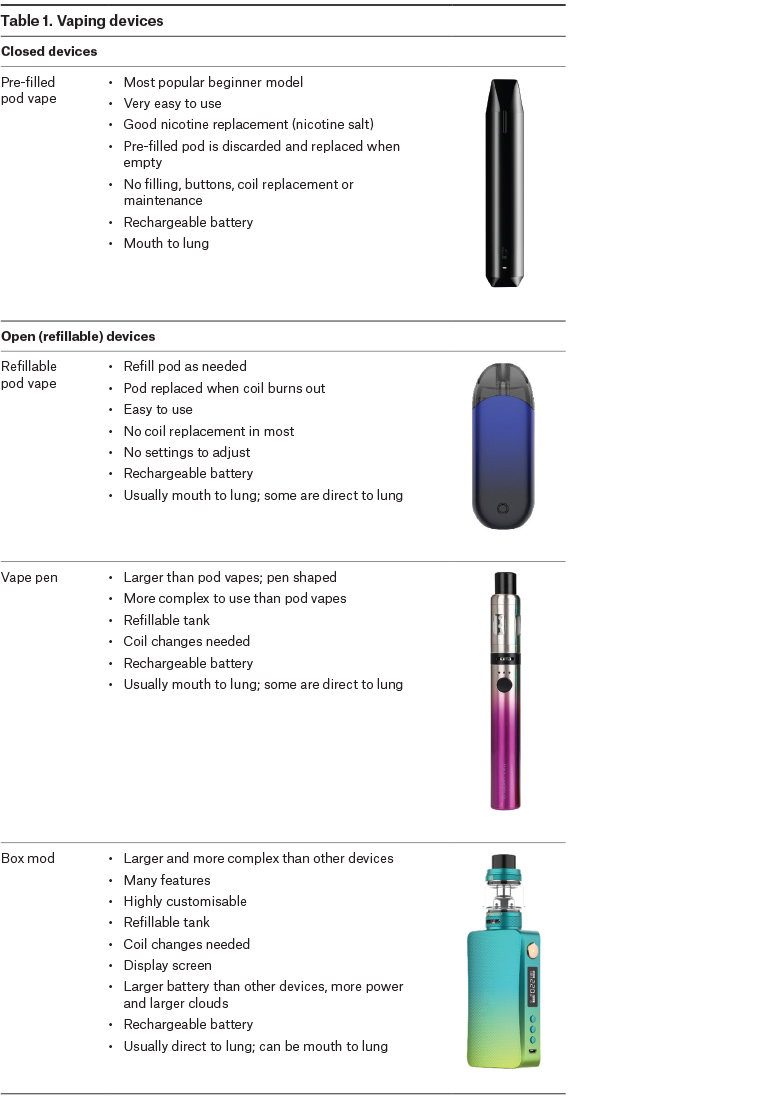

Vaping devices

All vaping devices (electronic cigarettes, vaporisers) have a tank or ‘pod’ (detachable cartridge) for e-liquid, a heating coil and a battery (usually rechargeable). The initial product choice is based on ease of use, similarity to a cigarette, nicotine delivery, vaping style, size and cost (Table 1).

Click here to enlarge.

Closed devices with sealed, pre-filled pods are strongly recommended for new vapers. These models avoid contact with nicotine, do not allow the addition of flavours and other substances and are very easy to use (Figure 1). Open, refillable pod vapes and vape pens are also available but are more complex to use and have a higher risk of poisoning than closed devices. Disposable devices are not generally recommended because of the large amount of environmental waste they create and questionable safety of some models.

All these models offer a ‘mouth-to‑lung’ vaping style that is familiar to most smokers, and they have a built-in battery (Table 2).

Figure 1. Parts of a pre-filled pod vape

| Table 2. Vaping terminology |

| Pod vapes |

Pod vapes have a detachable ‘pod’ (cartridge) containing a coil, wick and e-liquid. The pod can be connected to and removed from a battery. Some pods are pre-filled and single use, while others are refillable. |

| Mouth-to-lung vaping |

A two-stage inhalation style similar to smoking and used by most new vapers. The vapour is first drawn into the mouth and then inhaled into the lungs as a second step. When compared with DTL devices, MTL devices have a tighter draw, similar to a cigarette. MTL vaping is a more discreet vaping style and produces smaller clouds. Higher nicotine concentrations are used, typically 6–60 mg/mL. |

| Direct-to-lung vaping |

A style of inhalation in which the vapour is taken directly into the lungs in one movement, similar to a deep breath before diving into water. DTL vaping produces large clouds and stronger flavour and is also known as ‘sub-ohming’. DTL vaping use lower nicotine concentrations than MTL devices, typically 3–6 mg/mL. |

| Freebase nicotine |

Freebase nicotine is mainly used in low concentrations in high-powered devices, such as vape pens and box mods. It creates the familiar ‘throat hit’ (the sensation at the back of the throat) that is part of the smoking experience. At high concentrations, freebase nicotine can be harsh and irritating to the throat. It is used typically in a range of 3–20 mg/mL. |

| Nicotine salts |

Nicotine salts are made by adding an acid (eg benzoic, lactic or salicylic acid) to freebase nicotine. They are smoother to inhale and allow the use of higher doses with less throat irritation. Nicotine salts are absorbed more quickly than freebase nicotine and have a more rapid effect, similar to the nicotine from smoking. Nicotine salts are used in pod models and disposables, typically in the range of 20–60 mg/mL. |

| Coil |

The metal heating element that vaporises the e-liquid when electricity from the battery passes through it. A cotton wick draws the liquid to the coil from the tank or pod. |

| DTL, direct to lung; MTL, mouth to lung |

E-liquids

E-liquids consist of nicotine and flavouring (usually) in propylene glycol (PG) and vegetable glycerine (VG). Not all users need nicotine. For some, the behavioural replacement without nicotine is sufficient to reduce smoking urges.

There are two types of nicotine available: freebase nicotine and nicotine salts (Table 2). Nicotine concentration is usually expressed in mg/mL or as a percentage, for example, 12 mg/mL = 1.2%.

The starting nicotine concentration is based on the level of nicotine dependence and the type of device used. Table 3 is a guide for starting nicotine for mouth-to-lung vaping.

| Table 3. Nicotine concentrations for mouth-to-lung vaping |

| |

High dependence/heavy smoker |

Low dependence/light smoker |

| Concentration |

Type of nicotine |

Concentration |

Type of nicotine |

| Pre-filled pod vapes |

20–50 mg/mL |

Nicotine salt |

20–30 mg/mL |

Nicotine salt |

| Refillable pod vapes |

20–30 mg/mL |

Nicotine salt |

20–25 mg/mL |

Nicotine salt |

| 6–18 mg/mL |

Freebase |

6–9 mg/mL |

Freebase |

| Vape pens |

12–20 mg/mL |

Freebase |

3–12 mg/mL |

Freebase |

| Box mods |

6–18 mg/mL |

Freebase |

3–12 mg/mL |

Freebase |

Lower nicotine concentrations are used for direct-to-lung vaping, usually 3–6 mg/mL.

Vapers use different ratios of PG/VG depending on the desired effect, but 50/50 is a good starting point.

Beginners should be prescribed pre-mixed e-liquids that are ready to vape. Some experienced vapers mix their own, adding concentrated nicotine (100 mg/mL) to flavouring extracts, PG and VG. However, the RACGP guidelines advise that nicotine liquid at 100 mg/mL should not be prescribed because of increased risk of poisoning.

A wide variety of flavourings are available. However, the RACGP guidelines recommend that non-tobacco flavours should be avoided where possible because of limited long-term safety data.

Patient counselling

Patients should be instructed on correct use, side effects, when to quit smoking and vaping, and safety issues (Table 4). New users should be offered behavioural support and followed up within the first month to review progress.

| Table 4. Counselling guide |

| Rationale |

- Vaping is not risk free but is a safer alternative to smoking

- Vaping delivers nicotine and replicates the smoking habit and sensations without most of the toxins from burning tobacco

- Vaping can be used as a short-term quitting aid or continued long term if it is preventing relapse to smoking

|

| Correct use |

- Use when there is an urge to smoke or to relieve withdrawal symptoms

- Take long, slow puffs, approximately 3–4 seconds each

- Take 10–12 puffs as though smoking a cigarette or a have a puff or two when needed

|

| Advice |

- Coughing is common at first but usually settles over the first week

- The most common side effects are throat or mouth irritation, cough, headache and nausea. These reactions are usually mild and tend to settle over time

- Vape courteously around others and only where vaping is permitted

- Increase the nicotine concentration and/or puff frequency if you are experiencing urges to smoke

- Keep spare coils, adequate e-liquid supplies and a spare charged device available

|

| Duration of use |

- Stop smoking as soon as possible

- Try to stop vaping within 3–6 months

|

| Nicotine safety |

- Only buy e-liquids from reputable suppliers

- Keep nicotine out of reach of children and pets and store in child‑resistant containers

- Use gloves when handling concentrated nicotine (100 mg/mL) and clean up spills promptly

|

| Battery safety |

- Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions on charging

- Never carry loose batteries in your pocket or purse without a plastic case

- Do not leave devices unattended when charging

- Always use the charging cable supplied with the device

- Charging in a computer, television or game console is safe

- Use a low amp wall plug, usually 0.5–1 amp (phone or tablet chargers are rated ≥2 amps output)

|

Vaping becomes more effective with practice.21 It may take some time to find the right combination of device, nicotine concentration and flavour that works best.

Patients should be advised to quit smoking as soon as possible. Some smokers find vaping works immediately and stop smoking very quickly. Others continue to smoke and vape for a while (dual use) until they are ready to quit cigarettes. Fifty-four per cent of Australians who vape were also currently smoking in 2019.22

After quitting smoking, it is important to advise patients to cease vaping as soon as they feel comfortable that they will not go back to smoking, usually within 3–6 months, if possible. However long-term vaping is likely to be far less harmful than relapsing to smoking.

Quit rates can be increased by adding a nicotine patch23 and providing standard smoking cessation support.3

Patients should be advised about safe nicotine handling and battery safety. Nicotine liquid should be kept in child-resistant containers out of the reach of children and pets. Accidental poisoning in children is rare, but four children have died globally over the past 15 years from ingesting nicotine e-liquid, including one Australian toddler.24 A patient handout is available online (Appendix 1), which gives advice on the correct and safe use of vaping products.

Nicotine prescriptions

Nicotine e-liquids can be legally accessed with a private prescription from a registered Australian doctor through the Authored Prescriber Scheme or Personal Importation Scheme (PIS). The RACGP guidelines recommend three-monthly review with a maximum of 12 months of use, although some patients will require longer-term use to avoid relapse.

Table 5 shows examples of prescriptions for a three-month supply. Individual nicotine requirements range from 15 mg to 300 mg per day (average 100 mg) in the authors’ experience but can be much greater. The daily volume of liquid for mouth-to-lung vaping is typically 3–6 mL.

| Table 5. Sample prescriptions for three months’ supply |

| Pods |

Premixed

(for a specific commercial e-liquid) |

For compounding |

- XYZ-brand pods (1 mL)

- Nicotine liquid

- 30 mg/mL

- 1 pod per day

- Flavour: mint

- 90 pods

|

- ABC brand

- Nicotine liquid

- 12 mg/mL

- 5 mL per day

- Flavour: tobacco

- 500 mL

|

- Nicotine salt liquid

- 6 mg/mL

- 10 mL per day

- Propylene glycol/ vegetable glycerine 50:50

- Flavour: tobacco

- 1000 mL

|

Authorised Prescriber Scheme

Nicotine e-liquid and some devices can be purchased from participating Australian pharmacy shops and online pharmacies with a prescription from a doctor registered as an Authorised Prescriber for nicotine.1 Authorised Prescribers can prescribe for an unlimited number of patients for a five-year period. The application process has been streamlined and takes only several minutes at the Australian Government Department of Health website (https://compliance.health.gov.au/sas).

Pharmacies can supply commercial brands or compound their own e-liquids.25 All nicotine e-liquids supplied by pharmacies are subject to minimum safety and quality standards under the Australian TGO 110 standard.25

To ensure the prescription is used locally, the RACGP guidelines advise adding ‘for local supply only’ to the prescription or supplying it directly to the patient’s nominated pharmacy.

Prescriptions for commercial brands from pharmacies should include:

- ‘nicotine liquid’

- nicotine concentration in mg/mL

- recommended daily dose

- volume of liquid or number of pods (discretionary)

- brand name

- repeats if appropriate – the RACGP guidelines recommend limiting the prescription to three months’ supply.

Prescriptions for compounding should also include:

- nicotine type: salt or freebase

- PG/VG ratio (usually 50/50)

- flavour, if required.

Brand name is not required.

Personal Importation Scheme

All registered doctors are permitted to write prescriptions for importing nicotine e-liquid under the TGA PIS.26 The PIS allows patients to import up to three months’ supply at a time to quit smoking and up to 15 months’ supply in a 12-month period. Patients must send a copy of the prescription to the overseas vendor so it can be enclosed with the order.

The RACGP guidelines do not recommend importation of nicotine vaping product as the TGO 110 labelling and packaging requirements do not apply. If products are imported, the patient or the doctor are encouraged to check that these criteria are met.25

Prescriptions should include:

- ‘nicotine liquid’

- nicotine concentration in mg/mL or per cent

- recommended daily dose

- volume or number of pods for three months’ supply

- repeats if appropriate.

Conclusion

Vaping nicotine is another evidence-based quitting method for the GP’s toolbox. It is regarded in Australia as a second-line treatment for adult smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit with conventional treatments. People who vape using nicotine need a prescription to purchase it from a participating Australian pharmacy under the Authorised Prescriber Scheme, or they can import it from overseas.

Resources for general practitioners

Resources for patients