General practice registrars and supervised doctors learn through a workplace-based training and assessment model in which they integrate biomedical knowledge, practical clinical skills and professional practice into competent behaviour.1 This involves ‘supported participation’, ‘along a spectrum from passive observation to performance’.2 As part of a range of options available to support this workplace-based training and assessment, one such tool is consultation observation,3 also referred to as direct observation. In Australia, one form of consultation observation is the ‘external clinical teaching visit’ (ECTV). At an ECTV, a visiting general practice supervisor or medical educator observes and assesses a registrar’s consultations including clinical skills,4 overall competency5 and effective communication.6 The overall assessment provides the basis for feedback to the registrar, the tailoring of supervision to meet registrars’ needs,7 and criteria by which to judge their progress.

Consultation observation is particularly valuable because it occurs in an authentic setting8 and in real time. The consultation room is the major location for place-based consultation observation in general practice. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ General practice management toolkit: Starting a medical practice provides recommendations about the clinic facility, consulting rooms and furnishings.9 Growing an evidence base to better understand the influence of the context of the consulting room in consultation observation is crucial. This article explores assessor chair placement in consultation observation through the lens of the registrar as the observed and the supervisor as observer.

Methods

Design

Qualitative research gathers participants’ insights to better understand their personal experiences. This provides so-called ‘insider views’ of experiences and the contexts within which these experiences occur.10 This ‘emic perspective’ is then translated by the researcher to an ‘etic perspective’ through a process of analysis and reflection.10

Qualitative multimethod research was conducted to explore and identify important features and psychosocial dynamics of consultation observations as an assessment and educational tool. Qualitative multimethod research uses a combination of various qualitative methods11 to generate multiple forms of qualitative data.12 A component of this multimethod approach was one-to-one semi-structured interviews.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 17491).

Research participants

Following an open call for participants for observer/observed pairings at two Australian registered training organisations (Eastern Victoria GP Training and GPEx), nine pairs of registrars and their observers (supervisor or medical educator) were recruited. Sampling included participant pairs from both metropolitan (n = 6) and rural (n = 3) locations. It included registrars at various stages of training (general practice term [GPT] 1 n = 5; GPT2 n = 3; GPT3 n = 1).

Data collection

The one-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted virtually (mainly via Zoom) in the 2–6 weeks following completion of the respective ECTV or direct observation visit (DOV) with each participating supervisor or medical educator and registrar. The interviews explored their individual perceptions and experiences of the consultation observation, with the interview questions arranged around several broad focal points: the observer (supervisor/medical educator), the observed (registrar), the relationship between the observer and observed, contextual factors and other issues of importance to the participant. Of pertinence to this article, the open-ended question posed in the semi-structured interviews was:

Contextual factors: In this section, we want to reflect on the effect that the environment plays in consultation observation. Were there things about the immediate environment that impacted on the usefulness of the consultation observation [such as] the physical space?

Interviews were conducted by senior researcher fellows from one Australian registered training organisation. The interviews were conducted virtually between December 2018 and April 2019. They ranged in duration from 26 to 66 minutes and were digitally audio-recorded.

Initial data analysis

All audio-recorded interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were cleaned and de-identified prior to thematic analysis. The interview transcripts were thematically hand-coded using an inductive six-phase recursive process13,14 that included initial familiarisation with the data, generation of initial broad codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes and naming themes. The results of this primary data analysis will be detailed in other publications. Participating supervisors (S) and registrars (R) were assigned a numerical identifier for anonymity (eg S1, R3).

Secondary data analysis

In the initial data analysis of the transcripts of the one-to-one interviews, in the responses related to context, there was a focus for some respondents on chair placement between the assessor, assessed and the patient in the consulting room for consultation observation. Secondary data analysis was conducted to specifically explore this detail. Secondary data analysis is defined as using existing qualitative data that was collected for the purposes of a prior study.15 There are three different ways in which secondary analysis of data can occur, and one of these is whereby researchers re-use their own self-collected data to investigate new or additional questions arising from the primary research.16 In this instance, the new focus related to seating arrangements in consultation observation. Benefits of secondary analysis include it relieving the burden of researchers identifying, accessing and recruiting research participants.17,18 A further benefit of using self-collected data is the knowledge of the original in the first instance.

Results

In relation to the semi-structured interview question regarding the physical environment and the impact the immediate environment and physical space had on consultation observation, the secondary data analysis of the interview transcripts specifically looked for mentions of chair placement between the assessor, assessed and the patient in the consulting room. The positioning of participants in the consultation room in relation to others was discussed in various ways. Some supervisors expressed that they preferred to sit where they could see the registrar; others preferred to sit to where they could see both registrar and patient; other supervisors sat so that they could see the patient. These seating preferences, however, were contingent on the size and layout of the room. It was mentioned that that, at times, consultation room layout or other constraints – such as an additional person accompanying the patient – prevented the observer from sitting in their preferred seating position for consultation observation. Responses also highlighted implicit considerations related to the notion of agency in the chair placement.

Participants detailing the physical seating arrangements and placement of chairs during the consultation observation used descriptive metaphors to describe these physical placements. Metaphors are powerful means by which to organise one’s thoughts and to describe these to another who is/was not physically present. The secondary analysis yielded the descriptive metaphors of triangles, lines, compasses and clocks, with the overarching theme of triangles being the most insightful.

Triangles are defined with respect to their sides and angles. They show the relationship between three points. In this case, the three points are the registrar or supervised doctor, the supervisor or assessor and the main patient, and where they were seated in relation to each other. Some examples of these ‘where do I place my chair?’ or ‘where do I sit if I have a choice?’ considerations are as follow, supported by excerpted quotes from the research.

Isosceles triangles

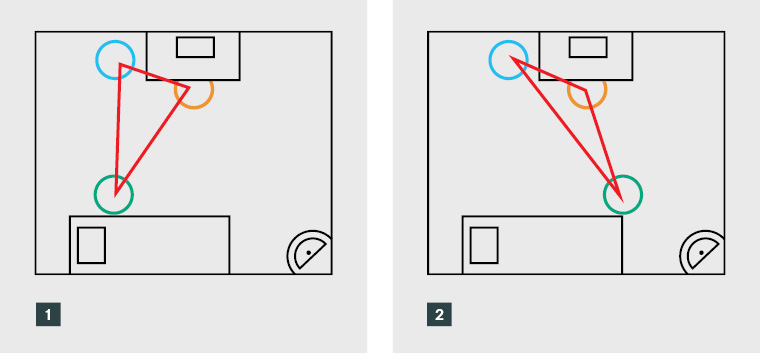

Isosceles triangles have two equal sides and one ‘odd’ side. The angles opposite the equal sides are also equal. Figure 1 depicts the position of chair placement in an observed consultation.

One supervisor captured the distinction of seating as an isosceles triangle well:

I do position myself so that I try and keep out of the consultation as much as possible ... [laughs] Certainly not an equilateral triangle, not by any means. What is it? Isosceles? … Yeah, that’s right. I’m sitting off to one side so that I’m not in direct eye contact with the registrar nor the patient. So, yeah, I’m sitting right off to one side [of both]. [S4]

Scalene triangles

The scalene triangle has no equal sides; each angle is uneven, and each side is of different length.

Figure 2 graphically depicts layout of chair placement with respect to the scalene triangle.

One supervisor’s reflection on the seating position in consultation observation in terms of a scalene triangle was as follows:

[I sit] skewed out to one side. Scalene, is it scalene? … Isosceles has got two sides that are the same … Yeah, it’s a scalene triangle! Yeah, if you draw yourself a nice scalene triangle, you can just see where you, you sort of just push that apex out as far as you can where you’re sitting. [S3]

Figure 1. Isosceles triangles and observed consultation chair placement

Figure 2. Scalene triangles and observed consultation chair placement

Another supervisor reflected:

More of a scalene or whatever you call those kinds of triangles … [T]he patient and my registrar were the shortest side on the triangle, and the patient and myself would be the longest side on that triangle and the registrar and myself would be somewhere in the middle. [S5]

Similarly, one registrar described that when they were doing the consultation with their patient, they could not actually see the supervisor. Rather, the supervisor sat behind them so that they had a direct line of sight with the patient and could see the registrar’s computer screen and the back of their head. However, they also noted that with this arrangement, they could see when the patient was looking straight past them to the supervisor.

Equilateral triangles

Equilateral triangles consist of three equal sides and equal angles; every side of the triangle is of the same length, and every angle is 60°. Chair placement as an equilateral triangle is depicted in Figure 3.

For some research participants, the equilateral triangle was used as a basis to refine their responses with regards to the triangle metaphor:

Interviewee: Yes, I usually sit, I think the arrangement’s probably more like triangular. So [the] registrar sits at the desk, the patient sits next to her and I sit sort of at an angle to both, yeah. [S3]

Interviewer: So, would you describe it as an equilateral triangle, with, you know, you’re equidistant between patient and registrar? …

Interviewee: Yeah, no actually. I try and sit out of the line of sight of the patient, just in case they do that whole deferring to me, I try and sit out of line of sight so they have to, and I often explain to, well I always explain to patients that you talk to the registrar, not to me. [S3]

Curved lines: Observer behind registrar

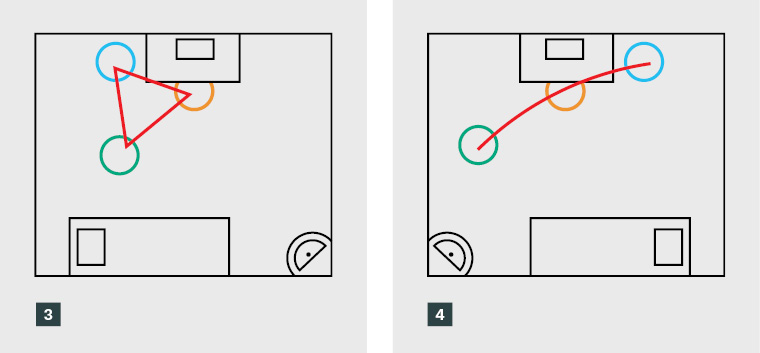

Curved or straight lines as a metaphor can also show relationship or direction. Related to the notion of triangles in terms of physical placement in the room, other participants described the positioning of chairs in terms of curved lines. Both examples to follow would relate to a scalene triangular placement. Figure 4 represents a curved line, with the observer sitting behind the registrar.

Explaining the seating position in the observed consultation, another supervisor explained that the consultation room:

Is not brilliantly laid out from an observer’s point of view and I have found it very difficult to find a great observer’s point of view over the years … So, for the most part I have sort of pushed myself back against the wall where I can see from an oblique angle, I can see sort of the side of my registrar’s face and I have a better view of the patient than I do of the registrar, which is not the most ideal from my point of view. [S5]

Figure 3. Equilateral triangles and observed consultation chair placement

Figure 4. Curved lines and observed consultation chair placement (observer behind registrar)

Curved lines: Observer behind patient

The second variant of the curved line metaphor is where the observer sits behind the patient, again correlating with the scalene triangle. Figure 5 represents a curved line, with the observer sitting behind the patient.

In contrast to the sentiments quoted in the previous section, one supervisor felt the inverse; that it was more important to sit behind the patient than the registrar:

Ideally, I would prefer to be in a situation where I am sort of almost sitting behind the patient. Not directly behind them so that they feel like, that would be a bit creepy, but I prefer to have a greater view of my registrar than I do of the patient ... [S5]

Figure 5. Curved lines and observed consultation chair placement (observer behind patient)

Compasses and clocks

Finally, but also related to the notion of triangular chair positioning in consultations, some conceptualise their workspace in terms of a compass or analogue clock face. With reference to the clock analogy, the angle of the two clock hands from their central point infers relationship to where the person is sitting. The angles of the clock hand from the central point infer relationship. In this analogy, ‘12 o’clock’ means straight ahead, ‘9 o’clock’ means 45° to the left, ‘3 o’clock’ means 45° to the right and ‘6 o’clock’ means 180° behind. An excerpt from the interview with one registrar demonstrates this relationship well, describing the physical placement of people in the room for the consultation observation session in the following manner:

I’m sitting at my desk. My computer is directly in front of me. To my left at 45° is the patient. To my left at 90° is the additional chair for a family member. If I’m looking to my right, directly at 90° is the examination bed about three metres away. And then if I keep turning back so if I’m facing 12 o’clock, so if I’m looking at 5 o’clock that’s where my supervisor was sitting … I can just give you clock numbers. Clock numbers is probably easiest. If my computer is at 12 [o’clock], the patient is at 10 [o’clock] and my supervisor is at 5 [o’clock]. [R8]

This description of angles and the clock face equates more readily to descriptions of the scalene triangle.

Discussion

The physical space in which workplace-based learning and assessment take place for general practice is the consultation room. Harris et al19 distinguished five dimensions of the physical environment in consultation rooms: architectural features, interior design features, social features, ambient features, and housekeeping and maintenance of the room. Of these dimensions, the first three have implications. Architectural features are relatively permanent characteristics, such as the spatial layout of the consultation room; the interior design features are defined as less permanent elements, such as furniture and the layout of the room; and social features encompass ways to accommodate assessors and patient support people in consultation observation. These dimensions may have an impact on learning and assessment.

Explorations of how physical space can influence teaching and learning have sparked the interests of educational researchers for over a decade now.20 Even in the most constrained room, consideration of layout can make a significant difference to learning outcomes.21 One room layout may invoke a power differential; yet another layout may see both teacher and learner more equally as co-users of a space.21 Power imbalances might be covertly suggested by the placement of chairs, not only between the general practitioner and the patient,22 but also between the supervisor and supervised doctor as trainee. Power imbalances can also affect learning, especially when the teacher is also the learner’s employer. Further, assessment of registrars and supervised doctors by their supervisors can exaggerate the power imbalance between them. This is particularly an issue when supervisors are also registrars’ employers and/or visa sponsors, or when registrars provide valuable workforce to the practice.7

In terms of chair placement in consultation observation, there is a tension between the physical layout and structure of the consultation room (architectural and interior design features); seating preference of the observer; and the agency of registrar as the observed (what the registrar would like) with the preferences of the observer. From a social science perspective, agency is the capacity of individuals to act independently and to make their own free choices. By contrast, structure relates to those factors that influence, determine or limit an agent and their decisions.23

Using the metaphor of triangles, what might the different triangular patterns and placement of the observed, observer and patient suggest? For example, an equilateral triangle chair placement may be suggestive of a shared power between parties, and a shared ownership and agency.

Limitations

There are several limitations to be noted here. First, the original research did not set out to explore chair placement and preferences in the consultation room specifically, or considerations of built pedagogy. Rather, it sought more generally to gauge the impact of contextual factors such as physical space on consultation observation. Second, the sample size was small, and while insightful, the findings cannot be generalisable. Third, the interviews did not purposefully explore agency in choice in the placement of chairs in consultation observation.

Further research

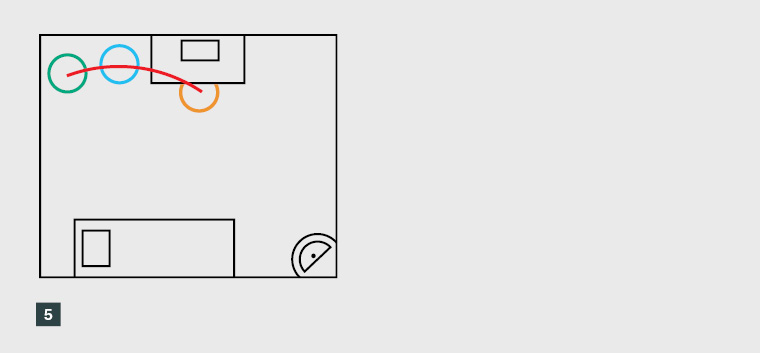

The importance of triangles in chair placement and relationship (Figure 6) warrants further research to investigate the link between how the observer positions themselves in the consultation observation through the placement of the chair – or their preferred seating position – and their perceptions of their role in the process (mentor, colleague, expert, etc). It also relates to agency in choice for the registrar, and how that might pertain to power imbalances. For example, it could be that an equilateral triangle in chair placement signifies shared agency, whereas scalene or isosceles triangular chair placement signifies other perspectives. Becoming aware of such non-verbal aspects playing out in the context of consultation observation is important. The redesign of the room, or alternative placement of chairs, can be an agent for change: changes in the consulting room as a learning space can potentially lead to changes in practice.21

Figure 6. Triangular chair placement in consultation observation

Conclusion

Metaphors are powerful descriptors that may be employed by participants to describe the setting to another who was not present at the time. This article explored metaphors, in particular triangles, to reference seating arrangements in consultation observation between the patient, the observer and the observed. These metaphors become powerful icons to explain relationships and potentially signpost other factors such as power differentials. The article suggests areas of future research to inform the training and assessment of registrars. It suggests reflection on consultation room layout and potential chair placement during consultation observation. It also encourages considerations of agency in chair placement, including inviting registrars to this discussion.

Key points

- Consultation observation (direct observation) is a key method in the workplace-based training and assessment of general practice registrars.

- The consultation room is the main learning space for workplace-based training and assessment.

- Learning spaces, whether physical or virtual (eg in remote contexts), can have a significant impact on learning.

- There is a tension between the physical layout and structure of the consultation room, seating preference of the observer and the agency of registrar in this choice.