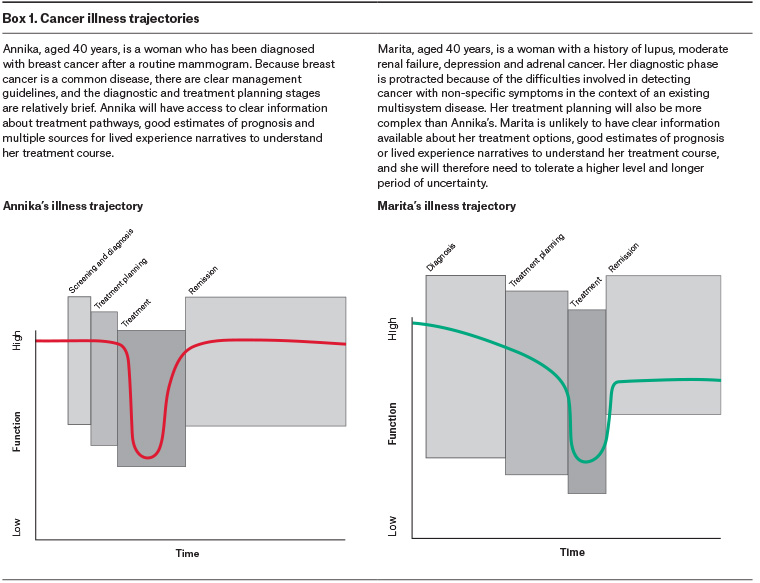

Uncertainty pervades cancer treatment and care. Similar to other diseases, cancer follows an illness trajectory (Box 1)1 in which each phase presents different challenges for the patient and their medical team. Uncertainty can be related to the process of diagnosis, treatment, remission or palliative care, and therefore it can be experienced repeatedly or continuously throughout a patient’s life. When the cancer is rare or the patient has complex comorbidities, the trajectory can become more difficult to predict. This means the patient and their general practitioner (GP) live with a high degree of uncertainty.2

The focus of this article is on three of the most challenging stages for the patient and their GP: the time before diagnosis, when the patient is not well but not yet classified as sick; the treatment-planning phase, when the patient and doctor are sharing decision making; and remission, during which the patient is no longer classified as sick but nor are they well. In these stages, there are times of great uncertainty and related anxiety and fear as the illness unfolds.

Click here to enlarge.

Liminal zones

Uncertainty about one’s wellbeing, disease trajectory, treatment prospects, mortality and social relationships cannot be viewed through the prism of biomedicine alone. The patient enters a complex phase in which they must make sense of their illness medically, psychologically and socially.

Liminality is a useful concept for considering the lived experience of uncertainty in illnesses such as cancer.3,4 Liminality describes situations in which people find themselves ‘betwixt and between’ states of being (including categories of health and illness). The term liminality, adopted from anthropology,5 was originally used to describe a life stage in which we move from one phase to another, such as adolescence, marriage and bereavement. Previous research has found that, for patients with cancer, liminality can begin in the pre-diagnosis period, a time when some patients are referred to cancer genetics screening or experience unexplained symptoms.4 For others it begins in the process of diagnosis, which is not always immediate or definite, and patients who are potentially sick must grapple with the possibility of immense change. These liminal experiences at the start of a possible illness trajectory assign individuals to a unique position in the healthcare system – in ‘a netherworld between healthy and the afflicted’.6 Understanding patient experience in this way can assist healthcare professionals in supporting their patients during these uncertain times.

While one might assume that remission resolves the experience of liminality, research suggests that feelings of uncertainty are sustained among cancer survivors.3,7,8 As well as dealing with therapy side effects, medical surveillance and bodily changes, survivors exist in a state of change and potential change. Fear of relapse combined with a realigned sense of self and altered social relationships can extend the lived experience of liminality long after treatment is finished.

A small body of research has examined the experiences of individuals doubly affected by the experience of liminality. For example, cancer as an adolescent has been described as a ‘navigation of two compounding transitional periods’.9 Already in the liminal period between childhood and adulthood, adolescent patients with cancer experience the overlapping liminal state of illness. As these liminal states exacerbate and disrupt one another, being in a dual state of liminality can impede the young person’s ability to progress through either experience.

Importantly, a number of authors remind us that the liminality need not always be negative, as not all change is necessarily deleterious. For example, Thompson describes the distress that comes with being ‘in-between’ as well as the personal growth people experience as they traverse a cancer diagnosis.10 Illness and its provisional nature can inspire and encourage change that is experienced as positive. Indeed, early work on the concept of liminality refers to a ‘stage of reflection’ where ‘the reformulation of old elements in new patterns’ occurs.11

One aspect of the healthcare professional’s role is to help patients at liminal stages integrate their past, present and future into a new sense of self. Acknowledging this transformation and marked change in identity can assist patients to generate meaning from their health crisis.

Managing diagnostic uncertainty

In the early stages of diagnosis, there is a period in which both the doctor and the patient live with deep uncertainty. In some cancers, this stage can be prolonged, particularly with cancers that present with common symptoms (eg cough and lung cancer, or back pain and multiple myeloma).12 There is also uncertainty when cancers have a long period during which people are ‘at risk’ before developing cancer (eg the progression of chronic myeloid leukaemia to its acute phase, or the latency period between exposure to asbestos and the development of mesothelioma). During this period, it is understandable that patients can feel isolated and vulnerable.

For the doctor, one important aspect of the diagnostic phase is harm minimisation, helping to navigate the risks of investigation against the risk of ‘missing something important’. Theoretically, clinicians know that healthcare occurs within a world of uncertainty. However, living with this uncertainty is difficult, and there is an art to sharing this ambiguity with patients.13 There is a fine balance between maintaining openness and honesty about the uncertain nature of medical work, and losing a patient’s trust. Trust diminishes with prolonged uncertainty and, as uncertainty is a common feature of the cancer trajectory, the GP’s capacity to manage care and the patient relationship can become more complex the longer uncertainty persists.14

The role of health numeracy and literacy in patient-centred care

As doctors, it is easy to overestimate the literacy and numeracy of our patients. In Australia, only 50% of people who leave school in year 10 have sufficient literacy to cope with everyday tasks.15 Patients with low literacy may have significant difficulty completing admission requirements, understanding medication instructions or reading information material, all of which can have a serious adverse impact on their health and safety.16 In a recent national health survey, only 11% of people strongly agreed that they could identify reliable sources of health information, while 17% of people disagreed or strongly disagreed.17 Low literacy is more common in disadvantaged populations, especially in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.16 Health literacy18 encompasses the ‘cognitive and social skills to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health’.19 Cancer involves a new and complex vocabulary and a bewildering exposure to complex health systems at a time when patients are vulnerable, anxious and unwell.

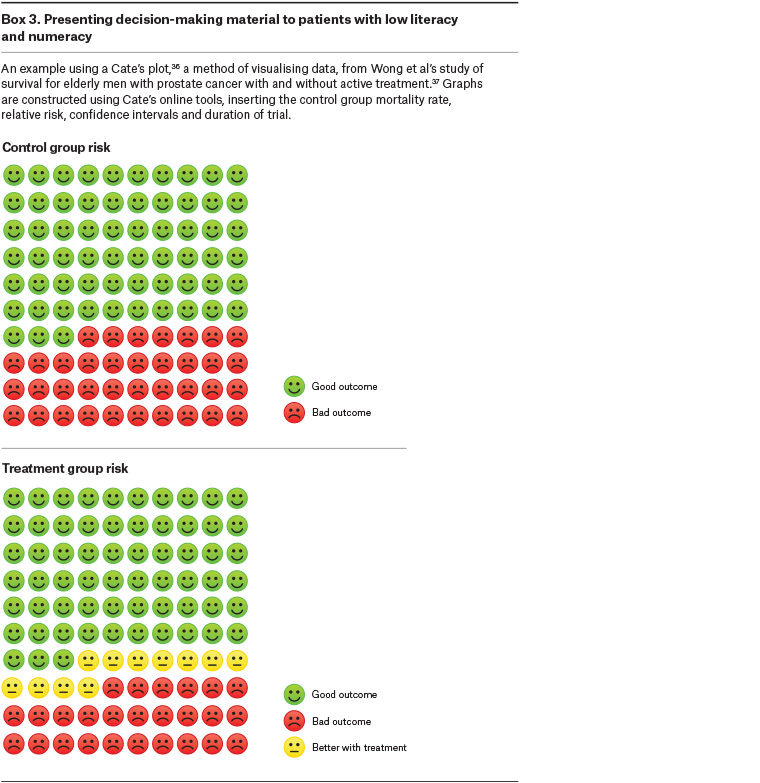

The complexity of risk – including the process of interpreting it and making decisions – also requires numeracy skills. While mathematics teaching is compulsory until year 10 in Australia, mastery of concepts such as probability, chance and data interpretation cannot be assumed. In a study of the US and German populations, approximately 20% of participants could not say which of the following numbers represents the biggest risk of getting a disease: 1%, 5%, or 10%. Almost 30% could not answer whether one in 10, one in 100 or one in 1000 represents the largest risk, and almost 30% of the study participants in both countries could not express 20 out of 100 as a percentage.20 Health professionals may have difficulty interpreting complex risk statistics as well, and this affects their ability to communicate effectively.21

Not every patient will interpret information in the same way, but there are some general principles to assist health professionals in communicating effectively. Absolute risk is more easily understood than relative risk, and number needed to treat statistics are often poorly understood.21 Visual displays of data seem to improve understanding, with icon arrays and bar graphs showing equal efficacy.21 Box 2 shows an icon array developed using an online method of generating visual representations of risk.

People with low literacy and numeracy experience considerable shame and are unlikely to volunteer these difficulties to health professionals.22 GPs are in an ideal position to check a patient’s understanding of their condition, their treatment regimen and their decision making. A simple question such as, ‘Cancer can be confusing and overwhelming. Can you tell me what the oncologist has told you about your condition?’ can allow patients the opportunity to express their confusion and ask clarifying questions in a safe environment. Practice nurses can help in this process, particularly checking a patient’s understanding of their medication regimen and future appointments.

| Box 2. Coping strategies |

|

Coping strategies include four distinct categories, each with their own focus.35

Appraisal

Appraisal focuses on how a person perceives the threat posed by their illness and how they understand their capacity to cope. Different patients will appraise the same diagnosis differently: one patient may see breast cancer as inevitably fatal; another will see it as an acute illness with a painful but inevitable recovery. People also differ in their sense of their own capacity to cope. While one patient may be confident that they have the financial, social, emotional and physical resources to manage their illness, another patient may be overwhelmed by the prospect and feel completely unable to manage.

Appraisal strategies help patients to accurately and realistically understand the threat their illness poses and their ability to cope, given the support they are likely to receive. These strategies involve education, with a clear description of the likely course of the disease and the treatment plan. Accurate appraisal is supported by written information, lived experience stories, peer support and time to ask questions with the relevant clinical team to address concerns. General practitioners may need to help their patients recognise their own strengths by reminding them of previous situations that they have managed well.

Problem solving

Problem solving involves managing practical issues, such as appointments, financial concerns, work and the management of treatment regimens.

Problem-solving strategies include helping patients prioritise; coordinating care; supporting patients with their administrative needs, such as work certificates; and discussing potential solutions to personal needs, such as parenting responsibilities.

Emotion-focused coping

Emotion-focused coping includes managing the distress associated with uncertainty, fear, pain and disability.

Emotion-focused strategies include positive strategies, such as exercise, social support, empathic connection with an appropriate healthcare provider, peer support and physical therapies, such as massage. Negative strategies also need to be managed. These include substance misuse, including misuse of prescribed medication, and other unhelpful behaviours.

Meaning-focused coping

Meaning-focused coping is used when appraisal, problem-solving and emotion-focused coping strategies are exhausted or inappropriate. These strategies are used when patients are coping by just getting through the days, one at a time.

Meaning-focused strategies include:

- distraction, such as visiting a pleasant place, watching a movie or attending a sporting event

- connection, such as visiting friends or family, or attending a social or peer group

- self-efficacy, such as participating in a work meeting, completing a piece of schoolwork or learning a new skill, such as a craft activity.

|

Managing uncertainty across the illness trajectory

During the diagnostic, treatment planning and remission phases, patients and their families can be troubled by anxiety and uncertainty and may have difficulty coping.4 Strategies for coping are described in Box 3 and can be adapted for all phases of the cancer trajectory.

Click here to enlarge.

Uncertainty can begin before diagnosis, at the screening stage. For patients at high risk of cancer (eg those with Lynch syndrome), complex surveillance regimens can lead to chronic anxiety.23,24 In essence, these patients are trapped in a permanent liminal zone: not sick, but unwell because of their permanent ‘at risk’ status.25 For patients at high risk, it is essential that barriers to surveillance (eg access and cost of colonoscopy) are addressed through advocacy and there is a clear plan for ongoing screening. Patients also benefit from learning to manage their risks via online information platforms, meeting with family members and discussing strategies for surveillance and anxiety management, and sharing knowledge and experience with others through social media.26 Addressing lifestyle issues that predispose them to heightened cancer risk brings a sense of empowerment. These strategies help patients regain a sense of control over their bodies and their futures.

At diagnosis, a person’s identity forcibly undergoes transformation,27 with some writers suggesting that the assumption of an identity as ‘a cancer patient’ is likely to be permanent, even with recovery.28 The moment of diagnosis is ‘marked by disorientation, a sense of loss and of loss of control, and a sense of uncertainty’.28 Patients describe surrendering their bodies, their autonomy and their agency to the medical system. Many lose their social connections and become profoundly isolated when friends and family are unable to cope with the world of illness.28

Support groups and peer support workers offer an important service in this space, helping patients with the biographical work of reclaiming and reshaping their identities in the wake of the trauma of serious illness.29 Frank writes that those who are ill ‘need to become storytellers in order to recover the voices that illness and its treatment often take away’.30 After the acute stage of diagnosis and treatment, GPs can also help patients by encouraging them to talk about their experiences and articulate their vision of recovery.

During remission, patients regain their autonomy and agency but are often unable to regain their pre-cancer sense of self. That is, the liminality of their experience changes but does not resolve. There is a sense of ‘relentless vigilance’ and ongoing anxiety as patients scan their bodies for recurrence and treatable symptoms.31 The person they expected to be, and the life course they expected to follow, are gone; the new identities they have adopted are unfamiliar and often frightening. Re-engaging with the world of home and work can be challenging as the familiar becomes strange and social relationships become uncomfortable. GPs can provide a consistent and ongoing therapeutic relationship to enable honest and open discussion about the challenging task of reshaping identity and lifestyle.

Some patients live with progressive disease, understanding that their chance of cure is low at diagnosis. Uncertainty pervades every part of their lives during this phase of illness. The continual oscillations between illness, treatment and recovery undermine their ability to adjust and adapt.31 For the GP, there is an opportunity to support the patient’s sense of identity and remind them of their values, skills and personal attributes while providing a consistent partnership throughout the course of the illness.

Throughout the trajectory, the risk of comorbid depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder is high.32 One of the great strengths of general practice is the life experience obtained by caring for patients across their life course. GPs are familiar with pain, suffering, death and fear, and it is these experiences that enable them to have open and honest conversations with patients with cancer who are trying to make sense of their experiences and plan their recoveries.33 GPs can also detect and manage common mental health comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, within an existing trusted relationship. However, there is evidence that detecting and managing mental illness in patients with physical disease is improved if screening tools are used, particularly with underserved patient populations.34

Conclusion

The diagnosis of cancer is a life-changing event that can herald a long journey of anxiety, uncertainty and change. Special consideration should be given to the patient’s life stage and social context in order to help them navigate the complex system of care. More than providing patients with information, it is important that GPs assist patients to interpret their situation and find a sense of power, autonomy and agency in an otherwise marginalising life experience.

Key points

- Liminal zones are times at which patients are stuck between wellness and illness, which can be unpleasantly uncertain.

- Prolonged uncertainty can cause strain on the therapeutic relationship.

- GPs have an important role in supporting coping.

- Patients with low literacy or numeracy can have difficulty making informed decisions and may need the support of their GPs to help them interpret data