There is an urgent need to clarify the value and expertise of generalist approaches in healthcare, especially as general practice faces demoralisation of the general practitioner (GP) workforce1,2 and changes in primary healthcare policy and structures. ‘Generalism’, defined as ‘expertise in whole-person care’,3 integrates biological and biographical knowledge and offers person-centred care, as well as continuity of care.3 This is challenging work that relies on generalist philosophy, priorities and practical skills.

There are relational and contextual challenges to generalist person-centred care in every clinical encounter. GPs intentionally sit near the pain, suffering and uncertainty in their communities, seeking to offer healing relationships that are humane and respectful. They become aware of social isolation, overwhelming financial needs and lack of timely access to affordable medical care. GPs often respond with innovative care,4 political advocacy5 and financial and personal generosity, such as seeking further training or working longer hours, bulk-billing and other unpaid work to increase access to care. This very same generosity can develop into distress or internal conflict if taken for granted of if the patient or community complains, asks for care that is not medically indicated or crosses the personal boundaries of the GP.6,7

Generalist care is undermined by systemic and bureaucratic devaluing of GP time and expertise, primary care policy that fragments care and encourages short transactional encounters and an excessive focus on disease or procedures.8,9 Clinical decision making in the face of uncertainty, undifferentiated symptoms, conflicted goals or chronic disease and grief is also cognitively, emotionally and morally difficult.10,11 In order to protect GPs from doubting the value of their work,12–14 it is important to understand generalism as so much more than biomedical service provision: it requires philosophical attitudes, overarching priorities and practical skills that are often unnamed and unnoticed.

In this article we offer encouragement to GPs by clarifying the nature and value of generalist work and by describing some practical priorities and skills that are part of the generalist toolkit.

Valuing the work of general practice: The Craft of Generalism

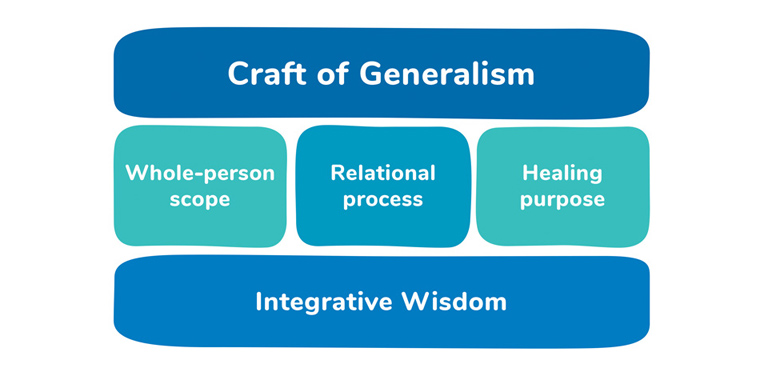

The ‘Craft of Generalism’ named in this paper (and outlined in Figure 1) aligns with generalist and transdisciplinary philosophical approaches to knowledge,15,16 as well as with ‘clinical pragmatism’. Clinical pragmatism is a philosophically robust approach to knowing that values plural sources of information, participatory forming of knowledge within relationship, pragmatic goals for how the knowledge will be used and a provisional (or humble) approach to certainty.17 For GPs, this philosophy reinforces the clinical priorities of broad whole-person scope, relational process, healing orientation and integrative wisdom (Figure 1).16 It includes a length, breadth and depth of scope that provides cradle-to-grave care, continuity, accessibility, inclusivity and capacity to delve beyond the presenting complaint to explore underlying issues when appropriate.18 Some foundational principles of generalism are outlined in Table 1.

Figure 1. First principles of the Craft of Generalism.

Figure 1. First principles of the Craft of Generalism.

Reproduced from Lynch,39 with permission by Routledge.

| Table 1. Underlying philosophy and priorities of general practice: Generalist whole-person careA |

| Craft of Generalism |

Definition |

| Primary care priorities |

| Positioned in the community for access |

Accessible and inclusive frontline healthcare working with diffuse undifferentiated presentations that does not exclude people based on diagnosis, eligibility or severity |

| Place-based healthcare |

A recognisable, consistent, hospitable and community-based entry point to the healthcare system |

| Continuity of care |

Intentional cradle-to-grave care that accompanies people through life and is not designed around life stage, disorders, body parts or procedures |

| Whole-person scope |

| A wide scope of care that is person-centred |

A generalist gaze that includes both biology and biography and is more than a narrow objectifying ‘medical gaze’

Attends to context, culture, community, personhood, body, inner experience, sense of self and spirit/meaning |

| A thorough approach to information gathering |

A broad attention to the whole (its length, breadth and depth), not just the presenting complaint or the body

Iterative cycles of understanding that rely on a provisional attitude to diagnosis that welcomes uncertainty and is wary of categories that may exclude other disciplinary knowledge, team contributions or new information |

| Relational process |

| Personal and embodied |

Involving the whole embodied self of the clinician, not just their cognition or their capacity to provide a service

A way of being, knowing, perceiving, thinking and doing |

| Relational process of care and understanding |

All consultations (including the apparently simple or ordinary ones) are part of building the therapeutic relationship; they are not just a transaction or an algorithm

Each encounter is relational, collaborative and tuned-in to the patient’s experience, context, relationships, expertise and meaning making |

| Healing orientation |

| A pragmatic focus on outcomes for the patient |

Assessment and treatment aimed at caring for the self of the person and reconnecting them with life (healing); not just about symptom reduction or technological interventions

Assessment prioritises the person’s future health through prevention and early intervention |

| Prioritising community connection |

Health as more than care for the individual with pathology: healthcare that actively attends to loneliness, social isolation, family dysfunction and community dislocation |

| Integrative wisdom |

| An integrative and humble wisdom |

Humble attitude to knowing: always open to new information and to complex forms of evidence (not just linear reductionist science)

Wisdom that uses integration, interpretation, iteration, discernment and pattern recognition of diverse, complex and transdisciplinary forms of knowledge |

| AThis table draws on the works of other previously published work.15,16,18–22,31,35 |

The Craft of Generalism has philosophical roots that value the personhood and expertise of both the patient and the GP and seek to care for the whole. Influential GPs have critiqued the ‘fault line’ that runs through a biomedical approach to medicine that is often blind to the whole person in their context and relationships, and have called on GPs to value general practice as an academic discipline that can bring generalist innovation to the wider health system.4,23–27 Others have highlighted the importance to generalist care of stories,28,29 the personhood of the patient,30 the relational ways of ‘being’ of the clinician,31,32 the complexity of people and systems,33 practical goals that help people live their lives,12,34 scholarly wisdom12,35 and ‘knowing’ that comes through experience.36 As new public policy impacts general practice, a return to the philosophical foundations of general practice is timely.

The generalist toolkit: Practical skills and priorities for whole-person care

Generalism is a craft that includes a sophisticated personal skill set that builds towards mastery with experience and training.37,38 Complex and conflictual patient encounters may lead clinicians to subconsciously narrow attention, adopt linear assumptions, minimise the importance of the relationship or become distracted from seeing the whole. The four priorities of the Craft of Generalism (whole-person scope, relational process, healing orientation and integrative wisdom) can protect the GP from getting stuck in these narrowed patterns. The five practical skills associated with these priorities (broad awareness, respectful connection, capable engagement, calm sense-making and owning yourself) can guide everyday consultations and provide a direction of travel to identify and circumvent blocks in more challenging consults (Table 2).39 These skills are an evidence-based approach that prioritises patients and clinicians feeling safe,39 and can equip generalists to persevere, and indeed thrive, as they perform this valuable work. We discuss each in turn below and outline each in more detail in Tables 1 and 2.

| Table 2. Craft of Generalism: Skills and priorities for general practice |

| Philosophical commitment |

Practical skill |

| Whole-person scope |

Broad Awareness |

| |

Focus on the patient

Helps the patient and GP to:

- put things in perspective and see what else may be important or helpful

- understand motivation and needs

- attend to culture, context, meaning and experience

- notice dynamics that help processes to get ‘unstuck’

|

| |

Focus on the GP:

- widens perspective and capacity to notice their own self: their tiredness, grief, motivation, values, relationships

|

| Relational process |

Respectful Connection |

| |

Focus on the patient:

- allows the therapeutic relationship between the patient and GP to weather disagreement, grief, frustration and even apologies

- includes consent and choice, as well as collaborative processes

- creates enough safety to build trust and disclosure of concerns

- prioritises patient autonomy and boundaries

|

| |

Focus on the GP:

- allows them to notice their own embodied response to the patient

- facilitates respect for their own expertise, sense of self and dignity

- allows GPs to create clear, respectful and protective boundaries

|

| Healing orientation |

Capable Engagement and Owning Yourself |

| |

Focus on the patient:

- enables, encourages and respects the patient’s capacity to engage with life on their own terms

- views the patient as a collaborator and leader in their own medical care

- focuses attention on prevention and early intervention for the sake of long-term wellbeing

|

| |

Focus on the GP:

- helps GPs to value and respect their own expertise and decisions

- provides security to manage patient disappointment or irritability

- inspires them to reflect on and attend to their own needs

|

| Integrative wisdom |

Calm Sense Making |

| |

Focus on the patient:

- helps the patient notice and make meaning from the story of their symptoms and experiences

- enables patterns to be recognised among fragments and to see through the surface to the deeper story (and notice inconsistencies and confusions)

|

| |

Focus on the GP:

- enables clear thinking and the use of pattern recognition to make sense of their own bodily experience

- actively values implicit memory, embodied sensation and tacit intuition to influence clinical decision making

|

Attending to the whole person with Broad Awareness

Offering whole-person care requires concurrent attention to the patient, the clinician, and the presenting concern.40 In complex situations, it is easy for patients and clinicians to focus narrowly on the perceived problem (eg chronic pain) or explanation (eg physical injury) without attending to the broader impacts of life experience, relationships or context. Such a narrow focus can result in care becoming ‘stuck’, where the perceived problem may represent only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ and cannot be effectively addressed without a broader perspective.

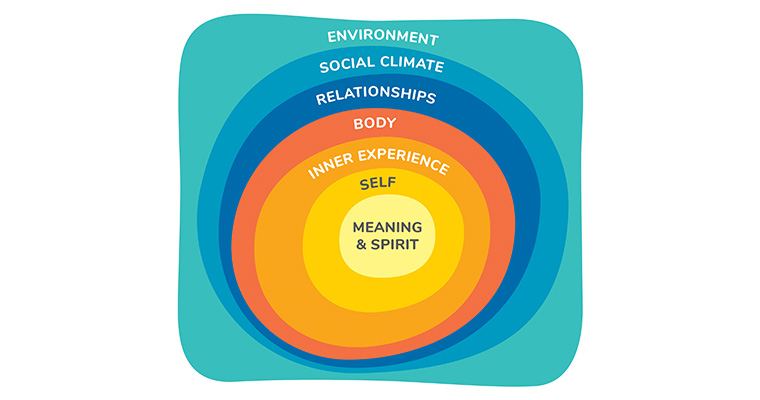

A helpful way to consider the whole person is to intentionally notice strengths, resources and threats in the multiple layers of the whole person.39 The Sense of Safety Whole-Person Domains39 (Figure 2) offer the generalist a framework for a systems review that can protect the clinician from too narrow a focus. Returning to this broad gaze draws attention to the wider environment, social climate (including injustice, racism and hopelessness), relationships, physiology, inner experiences, sense of self and spirit or meaning for each person (both patient and GP).39

Figure 2. Sense of Safety Whole-Person Domains.

Figure 2. Sense of Safety Whole-Person Domains.

Reproduced from Lynch,39 with permission by Routledge.

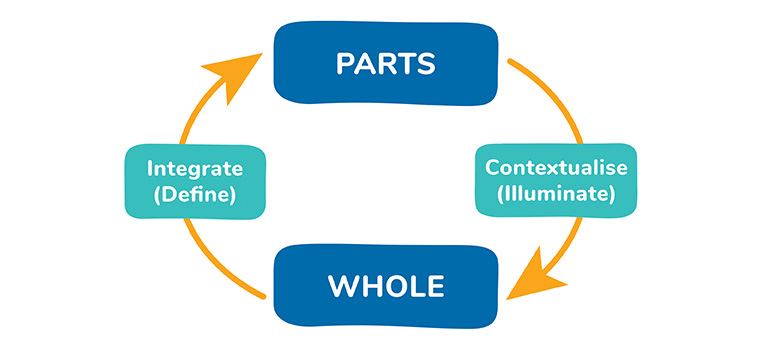

This wide view is about the content (the strengths and threats in each layer), as well as process, of Broad Awareness.39 Skilled GPs speak of processes of iteration, interpretation, integration and discernment that are part of Broad Awareness, noticing a part within a comprehensive wider whole.12,31,41 Hermeneutic approaches to knowing speak of attending wide for illumination and narrowing for definition42 (Figure 3) to maintain Broad Awareness. This breadth of focus helps both the patient and GP see a more nuanced, varied, personalised and comprehensive understanding of complex problems. It includes an awareness within the clinician of both their own and their patient’s complexity and needs. It includes the inner experience of the GP as part of that awareness: tuning in to embodied experience as part of the way clinicians make decisions. It also reveals a gift of complexity: more potential avenues for treatment and healing.

Figure 3. Hermeneutic cycle as per Ajjawi and Higgs.42

Figure 3. Hermeneutic cycle as per Ajjawi and Higgs.42

Reproduced from Lynch,39 with permission by Routledge.

Prioritising Respectful Connection in relationships

Disrespect and conflict within the GP–patient relationship can be one of the most challenging and demoralising situations faced by GPs. The generalist skill of respectful connection can protect the therapeutic alliance and help it weather grief and frustration. It also names a key goal for healthy relationships in both the patient’s and clinician’s own lives.

Respectful Connection should be prioritised in each consultation because it protects both the patient’s and clinician’s dignity and belonging.43 Respectful Connection is characterised by an attuned and trusting connection to self, other and environment.39 It facilitates emotional regulation and genuine disclosure and understanding.44 Respectful Connections are enacted through genuine caring interest in the person, warm tone of voice, respectful management of time, informed consent, confidentiality, open communication, repair of any relational ruptures (if possible) and collaborative decision making.45–50

Focussing on Capable Engagement and Owning Yourself as healing outcomes

Consultations where GP and patient goals and priorities are misaligned can be challenging and frustrating for both. Generalist care includes both GP and patient expertise and their differing goals. Therapeutic alliance requires a process of collaborative deliberation,45 which is immediately undermined if the GP or patient adopts dominating, dismissive or overly helpful or hurried approaches.

Conversely, Capable Engagement and Owning Yourself are two generalist skills that assist effective collaborative deliberation, are foundational for rehabilitation of the self and can be built into every consultation.34,39,51 Capable Engagement is purposeful and prioritises the patient voice, integrity, values and social connections52,53 as part of fostering patient autonomy, self-efficacy and hope (even in the face of ongoing chronic illness).54,55 Owning Yourself includes reflecting, knowing, accepting and being responsible for yourself.39 Fostering this in both clinician and patient is a key goal of quality generalist care.

Calm Sense Making as a journey towards Integrative Wisdom

The generalist skill of Calm Sense Making can help address the confusion, frustration and meaninglessness felt by both patient and GP when facing complex and unremitting presentations. Calm Sense Making is a reflective inner process of organisation, pattern recognition, digesting, understanding and adapting to what is really happening.39 For the clinician, this process involves clinical wisdom (phronesis)56–58 and the discipline of tolerating uncertainty59 and avoiding premature categorisation.60 These disciplines enable discernment of what is most important and what patterns are being enacted, and can help the clinician to notice themselves and their own motivation and meaning in their work. For the patient, sense making is deeply embodied in how the body regulates itself. It is a personal process of understanding and regulating emotions and understanding the meaning of symptoms or situations. Calm Sense Making is also a communal process that can happen in families as they adjust to change, and in whole communities as they create rituals to help a group understand what has happened (eg in a funeral).39 This relational reflective process helps the clinician, patient and wider community make sense of the healing journey.

Conclusion

Generalist whole-person care requires personal commitment and wise professional skills. Clarifying the underlying generalist philosophy can help GPs value their work and respect their place in the healthcare system. Naming and describing some practical priorities and skills can help clinicians apply the generalist gaze to complex clinical situations and decisions. Awareness of this wider frame can also help GPs maintain a person-centred approach towards their patients as complex people, and towards themselves as people and sophisticated knowledge workers (not just service providers or technicians) who use emotional, relational and embodied wisdom to do their work. Understanding the sophisticated craft and practical skills of generalist care could help both GPs and health policy makers value, respect and navigate the challenges of this complex and important work, especially at this time of change for Australian general practice.

Key points

- GPs who offer whole-person care have a generalist gaze that sees the whole person.

- The Craft of Generalism is a philosophically robust approach to diverse forms of knowledge that make up the whole.

- Generalists trained predominantly in the biomedical paradigm may not have the language to communicate the additional priorities, skills and wisdom that they bring to patient care.

- Generalist work is scientific, practical, relational, contextual and wise: it offers clear priorities and practical skills to navigate conflicting, confusing and complex situations.

- GPs need to care for themselves, because offering whole-person care to others is whole-hearted work and can be emotionally and physically exhausting.