The authors undertook a project examining burnout and wellbeing among general practice registrars – a concerning occupational syndrome facing specialty trainees with resultant personal, professional and economic costs.1–4 This project entailed three studies: a meta-analysis of 89 studies examining burnout levels and patterns among a pooled sample of over 18,000 postgraduate medical trainees;5 a hermeneutic literature review6 that thematically consolidated data from 36 studies involving family medicine and general practice trainees;7,8 and a qualitative study examining burnout and wellbeing as perceived and experienced by 47 registrars, medical educators, supervisors and program coordinators within Australian general practice training.9,10 The combined findings highlighted variability in burnout patterns based on trainee specialty5 and provided novel insights into the structure and function of trainee burnout and wellbeing.7,10 Effective interpersonal (eg comradery) and intrapersonal (eg normalising feelings of insecurity) change mechanisms, a need for interventions to meet local needs,8,9 and the complex interplay of individual (eg competence, insight), workplace (eg conflicts, workload) and systemic factors (eg stigma, workforce shortages) on general practice registrar wellbeing were also confirmed (unpublished data, SP, TE, DD, JB).

The authors conducted the present translational study to: 1. consolidate these findings; and 2. seek further feedback on preliminary intervention guidelines, which were subsequently formulated into a practical, conceptual framework. In doing so, the authors addressed key gaps in the available literature3,11–16 by concurrently targeting individual and organisational strategies, as is recommended,17–20 and by considering decentralised training contexts in which trainee education and practice occur across different organisations, such as Australian general practice training.

Methods

Guideline development

Data collection

The three aforementioned studies, involving a combination of 126 independent local and international studies, were chosen as the ‘sampling frame’.5,7–9 This was considered an up‑to-date and robust dataset given it comprised two comprehensive literature reviews and a further primary study designed to address gaps identified within the two reviews.

Analysis

Initially, SP (the first author) prepared a summary document for each study detailing key findings, which was imported into NVivo (V12, QSR International) to triangulate. Triangulation was accomplished using inductive thematic analysis underpinned by post-positivist grounded theory to identify overarching themes in the studies’ findings.21,22 Post-positivism was chosen to align with the aims of the present study in generating transferable findings. Grounded theory was chosen to allow themes to emerge from the data, potentially permitting new insights to be drawn from the studies’ collective findings. Using this information, SP generated a ‘triangulation table’ listing each theme and its supporting studies (refer to Appendix 1).

Using this triangulation table, SP then reviewed the themes to specifically identify burnout prevention and reduction strategies. He also reviewed the key findings of each study within the sampling frame for practical strategies that were suggested. These strategies were subsequently incorporated with those from the triangulation table, producing a preliminary list of 63 proposed guidelines along with a rationale for their inclusion based on the supporting themes. To maximise utility, SP then categorised each guideline into those actionable by registrars, practices, training organisations and the broader medical system. This initial set of guidelines was disseminated to the co-researchers (JB, DD and TE), and a meeting was held to discuss feedback and suggestions for improvements. Following this meeting, SP simplified and refined this list to 29 guidelines, which were re-distributed to the co-researchers, who approved this version. This process occurred between June and August 2020.

Consultation

The draft guidelines were subsequently discussed in two rounds of consultation within a single Australian general practice regional training organisation. This consultation process helped to assess the feasibility, acceptability and usefulness of the guidelines. Consultation was confined to a single training organisation to minimise contextual variance, which would likely have resulted in excessively generic suggestions. Indeed, context plays a critical part when designing an effective intervention.3

Round one

Data collection

The first round of consultation, held in August 2020, targeted key individuals from the training organisation representing different stakeholder groups. A focus group was chosen as the initial means of feedback to permit dynamic exploration of the guidelines. Eligible participants (members of the training organisation’s research and innovation committee that oversees the design and delivery of education, quality and research at the training organisation) were sent an invitation to participate. This committee included medical educators, supervisors, practice managers, registrars, education managers and administrators. Since the entire committee was invited, no further recruitment was conducted. Those who accepted the invitation were sent the list of draft guidelines as a pre-reading along with a written consent form to sign. The one-hour focus group was facilitated by SP, JB and TE.

At the commencement of the focus group, SP provided a brief overview of the project’s theoretical background. Participants then completed a brief survey to nominate the five guidelines that they felt needed further clarification or would be difficult to implement. From these responses, the facilitators identified the five guidelines that were most commonly selected. This process ensured a focused and thorough discussion of each contentious or problematic guideline, rather than superficial discussion of the entire list. This discussion followed a question schedule (Table 1). Within this structure, facilitators posed further questions to address emerging issues. In this sense, the authors considered the focus group to be semi-structured. Participants were invited to submit further feedback via email following the focus group if they desired.

| Table 1. Focus group schedule |

| Question |

Prompt/s |

| What barriers might you see for this recommendation/what problems are there with this recommendation? |

|

| What changes would you make to this recommendation? |

Is there anything missing from the recommendation? What? |

| Note: These questions were asked for each of the five guidelines nominated by participants. |

Analysis

With participants’ written consent (via the consent form), the focus group was audio-recorded using dictaphones. Additionally, JB and TE each took notes on whiteboards visible to the participants, and two participants voluntarily provided written feedback on all the guidelines. Following the focus group, SP transcribed audio recordings verbatim and removed identifying features (eg names). SP then compiled the feedback from the transcript, whiteboard notes and written feedback into a document summarising all suggestions, and then identified broader themes using thematic analysis – again using post-positivist underpinnings.21,22 SP adapted the guidelines in light of this feedback, thereby enhancing their specificity, and disseminated this list to the co-researchers for final approval.

Round two

Data collection

The second round of feedback sought registrar and supervisor feedback on the refined list of 31 guidelines via an online survey. A survey permitted efficient evaluation of the guidelines’ perceived acceptability, feasibility and usefulness. Piloting of the 15-minute survey was undertaken by the researchers to identify technical difficulties (eg incorrect logic jumps) and estimate the time requirements; no changes were made to the survey content as a result. Both registrars and supervisors were represented in the survey, with each group asked to rate the extent to which each guideline was feasible, acceptable and useful in promoting registrars’ wellbeing on a five-point Likert scale (from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’). Each group’s survey was tailored to ensure only relevant questions were asked (eg feasibility of registrar recommendations was not assessed by supervisors). An optional free-text box allowed participants to provide further feedback. At the conclusion of the survey, participants were thanked for their responses and offered the opportunity to enter their contact details to enter a prize draw, which comprised two $50 gift cards per group. Contact details were collected via a separate survey to maintain response anonymity.

Prospective participants (all community-based registrars [n = 228] and primary supervisors [n = 281] in one training organisation) were emailed an invitation to complete the survey. This sampling frame was chosen as it represented the entire target population within the training organisation in which the guidelines were being developed. The invitation included a participant information sheet that detailed the purpose of the research and how responses would be used. Invitations were distributed at the end of August 2020, following the revisions to the recommendations guidelines from the focus group. The survey was open for a fortnight. As the invitation was distributed to the entire sampling frame, no further recruitment occurred. Participants were informed in the survey that provision of any responses would be interpreted as having read the information sheet and providing consent to participate.

Analysis

Once the survey was closed, SP categorised both quantitative and qualitative responses into a document, removing any identifying details that had been included in the free-text boxes (eg locations). All responses were directly exported to a CSV file, with qualitative responses transferred into a Word document. The percentage of participants who endorsed a guideline (defined as those who selected ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly Agree’ for a given guideline) was then calculated. SP analysed qualitative responses using the same approach as for the focus group (ie listing feedback for each guideline and applying thematic analysis techniques to identify overarching themes). He then revised the guidelines in light of this feedback and distributed this to the co-researchers, who approved the final version in October 2020. Data from both rounds of consultation were stored on secure servers and only accessible to members of the research team.

Regarding reflexivity, SP was the primary researcher for the three studies on which the initial guidelines were based, while the remaining authors were involved in the analysis process of the three studies to varying degrees. Although all authors had a comprehensive understanding of these studies, this meant that SP was well placed to develop the initial set of guidelines. Importantly, all findings and guidelines were reviewed by each co-researcher. As each researcher came from a different professional background (general practice, medical education research, clinical psychology practice and research), this provided a forum in which to identify and discuss biases and assumptions. The two rounds of consultation further enhanced the rigour of the guideline-development process by including the perspectives of individuals from diverse professional backgrounds. Ethical approval for the present study was granted by the University of Adelaide School of Psychology Ethics Subcommittee (approval number 20/57).

Results

Focus group

Of the 13 committee members invited, eight participated in the focus group, representing training organisation staff, medical educators, registrars, supervisors and practice managers. Feedback on the guidelines focused on four general themes (refer to illustrative quotes in Table 2). The first centred on the importance of prevention: many were eager for early intervention, including workshops and resource dissemination. The timing of this intervention was also important, with suggestion that this occur as early as possible, even ‘… in the hospital space …’ prior to general practice training. The second theme concerned the need to integrate wellbeing throughout training to minimise stakeholder burden. For example, one participant suggested that, instead of having a new topic in the online curriculum, each ‘… topic might have a question … related to wellbeing …’. Participants also discussed the importance of ensuring that stakeholders, particularly registrars, were aware of and could easily access referenced resources (eg information pamphlets). Last, both supervisors and practice managers believed that they needed greater support to incorporate wellbeing into registrar placements and to enhance the teaching quality of their practice. To this end, they were eager for the training organisation to provide training, information resources (eg online information sheets) and tools so ‘… they’ve got somewhere to go with it’.

| Table 2. Illustrative quotes of feedback themes from focus group |

| Theme |

Quote |

| Importance of prevention |

Participant 1: So orientation is two days of full-on stuff where people are just obsessed about, like item numbers, so I almost think this [wellbeing workshop] needs to be before that, so if we’ve got them in the hospital space, that’s the space to do something like this …

Participant 2: That’s the time they’re getting bullied, harassed, all that sort of stuff, they need … it before they hit the hospital really … They should be getting it in their … final year of medicine, maybe their first year. |

| Integrating wellbeing throughout training |

I’m just wondering, you know, because we integrate Aboriginal Health throughout our online curriculum, don’t we … so it’s not that necessarily the whole thing is on wellbeing, but that topic might have a question related to Aboriginal Health or it might have a question related to wellbeing, maybe that’s the kind of thing we need to think about … |

| Stakeholder awareness of, and access to, resources |

… sometimes it can be hard for registrars to navigate the website to find specific information like this [resources] … so just making it really clear to have that these are resources for registrars specifically about burnout would be really important, otherwise they can often get lost in the website like a lot of information does.

… I think we all have a duty of knowing where those resources are and making sure that everyone knows so that, depending on who you go to, we can give you that consistent response. |

| Support for supervisors and practices |

I’d say we also need to give the practice managers and the supervisors some tools to use for this … so that, if they’re focussing on wellbeing, they’ve got somewhere to go with it. |

On the basis of this feedback, the guidelines that were specifically targeted to practices were reworded to enhance specificity (eg linking a ‘collegiate practice culture’ to staff wellness) and emphasise the importance of both training organisation resources and the need to integrate wellbeing into education. To enhance clarity, certain guidelines were supplemented with sub-guidelines that focused on specific aspects of the respective overarching guidelines. An additional two guidelines were included, resulting in a final list of 31 guidelines.

Survey

Survey responses were lower than anticipated, with only 25 individuals commencing the survey, and complete data available from nine registrars and nine supervisors. Given the very low response rate (3.5%), little weight was given to the quantitative data (refer to Appendix 2). Rather, participants’ qualitative feedback and suggestions were examined, with four key themes identified (refer to Table 3 for illustrative quotes). In particular, although participants were generally supportive of a guideline ‘in principle’, some expressed uncertainty about how to enact certain guidelines. Accordingly, they requested ‘… practical advice on how [these] can be implemented in different settings …’. Moreover, some registrars indicated that while they would be willing to enact the registrar guidelines, they questioned whether the training organisation would support these efforts. A further theme, again raised by registrars, concerned perceptions that the guidelines assumed that burnout was caused by registrars’ failures rather than organisational or structural issues. Finally, some supervisors expressed concerns that promoting registrar wellbeing could come at the expense of the wellbeing of other practice staff.

| Table 3. Illustrative quotes of feedback themes from survey |

| Theme |

Quote |

| Need for practical guidance |

[Training organisation] should make practical recommendations on how registrars should ‘explore’ this and how they can implement them, as well as provide examples. This is not something that is easy for a lot of registrars. [Registrar]

Practical advice on how this can be implemented in different settings (ie metro, rural, unusual working hours) would be useful. [Registrar]

Psychological strategies are often hard to put into practice without another party to discuss these stressors. They are helpful, as long as the registrar has a trusted supervisor or mentor to be able to discuss the stressors. [Supervisor] |

| Training organisation supportiveness |

It [implementation of Registrar Guideline #1] would need to have the support of [training organisation] and practices. [Registrar]

Practices need resources to achieve this [fostering a collegiate practice culture that promotes staff wellness]. [Supervisor] |

| Guidelines assume that burnout is caused by registrar failures |

The way these recommendations are worded, it makes it seem that burnout is inevitable and worse, somehow the fault of the registrar. A business that expects a certain number of its employees to be unable to work due to, essentially, unsafe work practices should be shut down. Why should we accept it as common and expected in [general practice] training? [Registrar] |

| Promoting registrar wellbeing at expense of others’ wellbeing |

Difficult as supervisors have the same burnout issues. Everyone can’t take leave, reschedule hours (which also impacts administrative staff) etc. Sadly not a perfect world and private practice is no different to any small business – with fixed costs etc. etc. – so while I completely accept that registrars are not there to generate vast amounts of income they do need to pay their way and cover all the costs of employing them. [Supervisor] |

On the basis of this feedback, minor wording changes to the guidelines were made to enhance their specificity (mainly through adding examples) and acceptability. For registrar guidelines, further explanatory notes were also necessary to minimise perceptions that the guidelines were blaming registrars for experiencing burnout. Additionally, two registrar guidelines (regarding proactive preparation and development of a ‘burnout contingency plan’) were merged given their common theme of preparation.

Final guidelines and conceptual framework

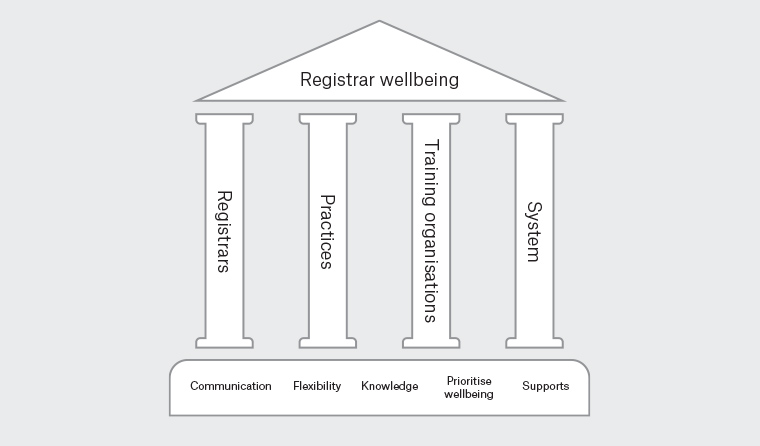

Ultimately, a list of 30 tentative guidelines for promoting general practice registrar wellbeing and preventing and managing registrar burnout was developed. These guidelines are provided in Appendix 3. Broadly, the guidelines aim to minimise threats to registrar wellbeing, build registrars’ capacity to manage such threats and enhance supports for registrars. To aid conceptual understanding and implementation of these guidelines, a broader framework was developed (Figure 1). At the base of this framework lie five fundamental, interrelated principles that the guidelines draw on:

- communication – open channels of communication are critical to ensure that everyone understands the needs, views and current circumstances of others

- knowledge – all stakeholders need to be informed of wellbeing-promotion and burnout-management strategies, as well as acknowledge each individual’s needs and circumstances

- flexibility – being willing to negotiate with each other to minimise unnecessary stress

- prioritising wellbeing – acknowledging the importance of wellbeing and ensuring it is not forgotten among competing demands

- supports – stakeholders supporting each other to help each overcome barriers that threaten wellbeing.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework for the promotion of registrar wellbeing

With these principles as a foundation, each group’s guidelines stand to collectively promote registrar wellbeing. Notably, each group’s guidelines are also complementary, showing that registrar wellbeing is a shared responsibility. When one group does not support registrars’ wellbeing, this increases the load on the remaining groups and threatens registrars’ wellbeing. The authors want to encourage readers to view this framework as the overarching spirit in which to understand these guidelines rather than viewing them as fixed prescriptions. Indeed, these guidelines will require tailoring to different contexts and over time as training models and practices continue to evolve.

Discussion

The present study sought to offer guidance for general practice registrar wellbeing promotion as well as burnout prevention and management. Draft guidelines were developed and then embedded within an overarching framework informed by the underlying research to enhance the guidelines’ understanding and acceptability. While other frameworks have tended to focus on a specific level of intervention (eg organisational leadership or learning environments) or have provided distinct organisational and individual strategies,3,11–13 the framework presented here deliberately spans multiple groups and settings in the general practice training context. The resulting conceptualisation incorporates multilevel complementary elements that are critical to the effectiveness of interventions to reduce trainee burnout and improve wellness.18–20 Moreover, while sharing similar content to other recommendations for doctors’ wellbeing,23,24 the current framework provides specific guidance for designing and implementing interventions within a decentralised training model. With further consultation across different general practice trainee settings, the current guidelines offer an important first step towards facilitating translation of the Every doctor, every setting recommendations, fulfilling a specific need for guided and coordinated action to support and enhance trainee’s mental health.24

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the present study was its use of iterative consultation. Feedback from different groups was explored and incorporated into a simple conceptual framework to facilitate understanding. Our deliberate focus on the Australian general practice training setting also permitted the development of tailored guidelines for maximal utility. However, this also comes at the expense of generalisability to other contexts. Furthermore, feedback was only sought from individuals in a single training organisation. Given this was a pilot study, stakeholders from other training contexts might want to adapt these guidelines, informed by the framework’s principles, to optimise their relevance within their specific contexts. Another limitation was the small sample size for the registrar and supervisor feedback surveys and the use of a convenience approach to sampling, with a considerable risk of response bias. Consequently, quantitative data should be interpreted with caution, particularly since respondents do not necessarily represent the broader registrar and supervisor populations. Given the present study was completed by the same research team that undertook the studies that formed the evidence base for the present study, there is a possibility of confirmation bias in the guideline synthesis. The authors minimised this by openly discussing their views during the project and by seeking to publish their previous studies to enhance transparency. Last, while the proposed guidelines are evidence informed, the effectiveness of their implementation is untested. The implementation and adaptation of the guidelines across training situations will need to be evaluated to ensure both feasibility and impacts on trainee wellbeing and burnout.

Conclusion

The present study provides an evidence-informed framework and prioritised guidelines for approaching Australian general practice registrar wellbeing promotion and burnout prevention and management. The resulting conceptual framework offers complementary strategies to enhance registrars’ wellbeing as well as improve responses to burnout within a specific training context. With further research and development, this framework might also help to design and deliver programs to improve wellbeing in the broader general practice context, consistent with the Every doctor, every setting agenda.