Australia has one of the highest obesity rates in the world,1,2 with a combined prevalence of overweight and obesity of at least 60%.3 Australian clinical practice guidelines base obesity treatment on body mass index (BMI) and complication status.2,4 Healthcare professionals (HCPs) report having limited training and few effective therapeutic approaches and/or tools at their disposal,5–7 and obesity stigma inhibits the deployment of effective strategies at both individual and population levels.7,8

There is significant inequity in accessing effective treatments in the Australian health system, particularly allied health support, adjunctive medical therapies and bariatric surgery.9 This is due, in part, to reported lack of HCP knowledge and training, inadequate integrated clinical services for obesity management, particularly in rural and remote areas,9 a funding system with restricted reimbursement for obesity management10 and inequitable access to effective publicly funded treatments.9

The Awareness, Care & Treatment In Obesity Management – An International Observation (ACTION-IO) study (NCT03584191) was a cross-sectional survey conducted in 11 countries. The study aimed to investigate the attitudes, behaviours and perceptions of people with obesity (PwO) and HCPs regarding obesity management.11 The results showed a nine-year delay between Australian PwO beginning to struggle with weight and first discussing their weight with an HCP,11 whereas the global ACTION-IO analysis found a mean delay of six years.12 During this period, many PwO will develop complications of obesity13 and/or progress to more severe stages of obesity.14 In this paper we explore barriers to effective and comprehensive obesity care in Australia, including barriers to having an obesity consultation, making and discussing the diagnosis of obesity and arranging a management plan that includes a follow-up appointment.

Methods

The cross-sectional, non-interventional, descriptive ACTION-IO study collected PwO and HCP data via an online survey in 11 countries.11,12 Full methodologies, including recruitment strategies, have been published elsewhere.11,12 The survey responses were self-reported and not verified. Australian data were collected between 13 September and 10 October 2018 and are reported here. The online survey was programmed by the third-party vendor, KJT Group (Honeoye Falls, NY, USA), who also oversaw data collection. Data analysis was conducted by KJT Group using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), Stata version IC 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Bellevue, WA, USA).

The study inclusion criteria for HCPs defined them as medical doctors with two or more years of clinical experience, who spent ≥70% of work time in direct patient care and had seen ≥10 patients with obesity in the preceding month. General, plastic or bariatric surgeons were excluded to avoid response bias because these specialities do not typically provide long-term care to patients. HCPs were not targeted demographically, and data are unweighted. All authors had access to all data in the study, which was approved by the University of Sydney Human Ethics Committee (Project no. 2018/591).

To be eligible for inclusion in this study, PwO recruited in Australia had to be aged ≥18 years with a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2 (based on self-reported height and weight), not pregnant, not participating in intense fitness programs or body building, not having experienced significant unintentional weight loss in the six months prior and willing to provide information concerning income or race/ethnicity. Demographic targeting and weighting ensured that the PwO group was representative of the general population.

Results

Perceptions of obesity as a disease

Response rates and PwO and HCP characteristics have been reported elsewhere.11 General practitioners (GPs; n = 100) constituted 50% of the HCPs surveyed. The ‘other specialist HCPs’ (n = 100) were predominantly cardiologists (n = 50) and endocrinologists (n = 41). Most PwO (76%), and even more HCPs (98%), agreed that obesity is a chronic disease. Most PwO (89%) and HCPs (91%) felt that society and the Australian healthcare system were not meeting the needs of PwO.

Among the Australian PwO surveyed who had discussed weight/weight loss with an HCP in the past five years, the mean delay between the PwO beginning to struggle with weight and first discussing their weight with an HCP was nine years (reported previously11). To obtain these data, PwO were asked at what age they had first struggled with weight, and their age when an HCP first discussed their excess weight or recommended that they lose weight. The time gap between these two periods was calculated for each individual respondent and the results are summarised in Figure 1A; 72% of respondents were aged at least 36 years when they began these conversations.

Figure 1. Self-reported weight management experience of people with obesity (PwO) in Australia. Healthcare providers with whom weight was discussed. Click here to enlarge

A. Number of years between PwO first becoming concerned about their weight and having discussions about weight management with a healthcare professional (HCP). B. Proportion of Australian PwO reaching each stage of the obesity management pathway as reported by PwO. Of all the PwO who were surveyed, 53% had discussed weight/weight loss with an HCP in the past five years, 47% of those (25% of all PwO) reported receiving a diagnosis of obesity and 29% of those (15% of all PwO) had a follow-up appointment scheduled specifically regarding weight. C. HCPs with whom Australian PwO report having ever discussed their weight. Percentage values are weighted to demographic targets.

*Data on obstetrician/gynaecologist not collected for males. GP, general practitioner.

Weight management discussions and obesity diagnosis

Australian chronic disease management guidelines recommend systematic discussion, assessment, goal-setting and follow up.15 However, despite widespread global recognition of obesity as a chronic disease, there were marked reductions in the proportion of patients progressing through an obesity care pathway from discussion to diagnosis and then to follow up (Figure 1B). In this self-reported survey, although 53% of PwO had discussed weight/weight loss with an HCP in the past five years, only half (25% of all PwO) of those had been formally diagnosed with obesity, and 29% (15% of all PwO) had a follow-up appointment scheduled specifically regarding weight. Most (96%) PwO with a follow-up appointment scheduled reported that they had attended or expected to attend their appointment. Their GP was the most common HCP with whom PwO had discussed weight (Figure 1C).

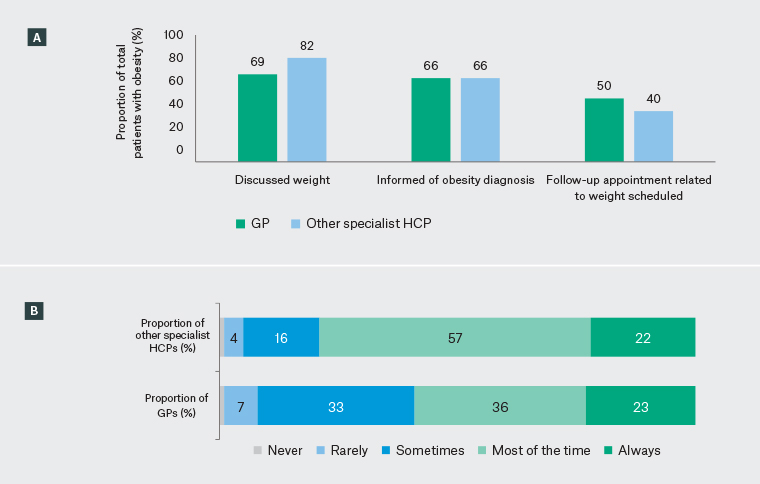

GPs reported discussing weight with 69% of their patients with obesity (Figure 2A), and that 39% of these conversations were initiated by patients. Other specialist HCPs stated that such conversations took place with 82% of their patients with obesity (Figure 2A), and that patients broached the subject 24% of the time. Both GPs and other specialists reported informing 66% of their patients of their obesity diagnosis (Figure 2A). Less than one-quarter of both groups stated that an obesity diagnosis is always recorded in their patients’ medical records (Figure 2B). Fewer GPs than other specialists reported recording the diagnosis ‘most of the time’. GPs scheduled follow-up appointments regarding weight management with a higher proportion of patients than other specialist HCPs (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Healthcare professional (HCP)-reported weight management experience in Australia. Click here to enlarge

A. Proportions of patients with obesity for whom general practitioners (GPs) and other specialist HCPs report discussing weight, informing of an obesity diagnosis and arranging follow-up appointments related to weight. B. Frequency of recording obesity diagnoses in patients’ medical records, journals, or histories, as reported by GPs and other specialist HCPs. Percentage values are weighted to demographic targets.

Setting and meeting expectations for weight loss

Most PwO (58%) would set a goal of >10% body weight loss (mean 14%) and reported a mean 19% weight loss to reach their ‘ideal’ weight. PwO who discussed goals with HCPs reported HCP-recommended weight loss targets of a mean of 14%, which, although aligned with PwO goals, is higher than the 5–10% typically achievable by non-surgical therapies currently available in Australia.16

In this self-reported study, 5–10% weight loss was rarely met and maintained, highlighting the difficulties of weight loss in the face of metabolic adaptation. Only 36% of PwO reported having lost ≥5% body weight over the past three years. Of those, only 27% maintained this for one year or more (10% of the total PwO cohort in this study). At least 10% weight loss was reported by 16% of PwO over the same period; only 35% of these PwO maintained this weight loss for one year or more (5% of the total PwO cohort in this study).

Methods for managing weight

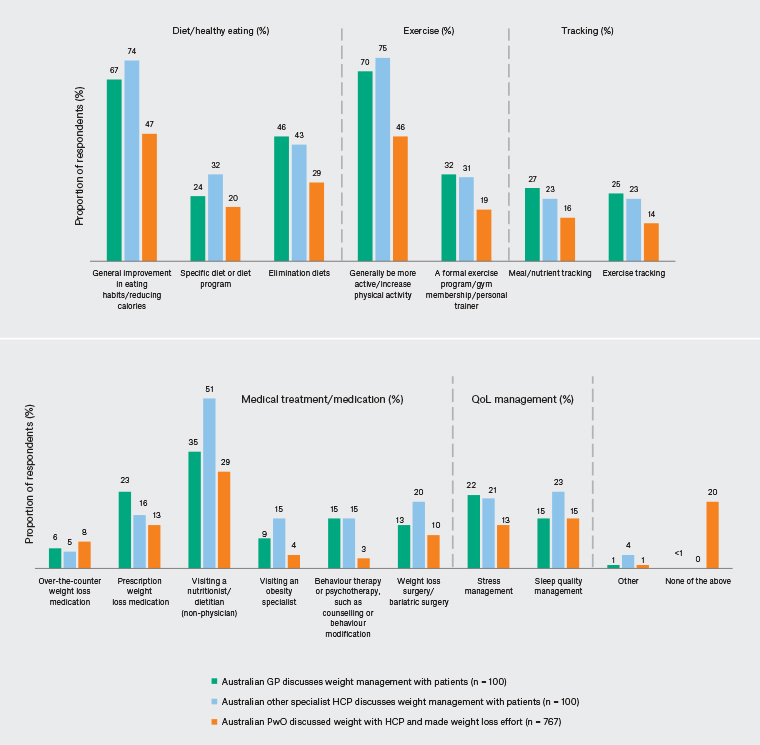

Methods for weight management most often recommended by both GPs and other specialist HCPs were dietary changes/healthy eating and exercise (Figure 3). Although reliance on general lifestyle changes alone may be insufficient to meet weight loss targets set by HCPs and PwO,17 formal programs and expert referrals were less frequently recommended.

Other specialists reported that they were more likely to recommend nutritionist/dietitian review or bariatric surgery than GPs. GPs more frequently reported recommending prescription weight loss medication. PwO having discussed weight with their HCP and made weight loss efforts reported receiving the same recommendations, but with lower percentages for most methods (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Methods for managing weight recommended or discussed between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and people with obesity (PwO). General practitioners (GPs) and other specialist HCP data reflect the proportions of patients for which HCPs reported recommending each method. PwO data reflect the percentage of patients who reported they had discussed each method with their HCP. Percentage values are weighted to demographic targets. QoL, quality of life. Click here to enlarge

Thirty-nine per cent of PwO and 59% of HCPs perceived that the prices of obesity medication, programs and services were barriers to weight loss. Most PwO respondents reported they would rather lose weight without the use of medication (70%) or bariatric surgery (83%). Fewer other specialist HCPs (51%) and still fewer GPs (32%) thought their patients would rather lose weight without using medication. Similarly, 42% of other specialists and 28% of GPs thought patients would rather have surgery than use lifestyle measures alone. The reasons for this were not explored in this survey.

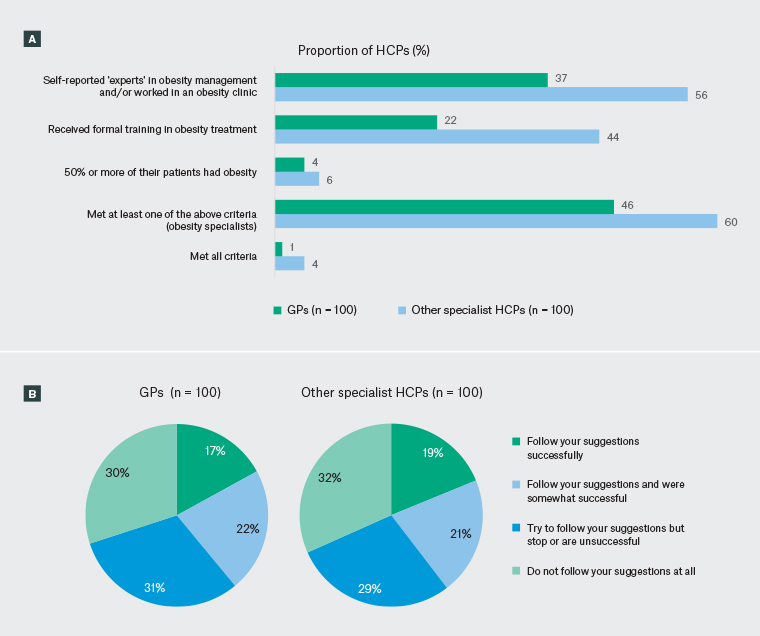

More other specialists than GPs considered themselves ‘experts’ in obesity management and/or worked in an obesity clinic (56% vs 37%) and reported receiving formal training in obesity treatment (44% vs 22%; Figure 4A).

GPs and other specialist HCPs reported that a mean of 31% of their patients did not follow their recommendations (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Healthcare professional (HCP) classifications and perceptions of patients following weight management suggestions in Australia. Click here to enlarge

A. Self-reported obesity expert classifications, as reported by general practitioners (GPs) and other specialist HCPs. B. Proportion of patients with obesity who follow recommendations, as perceived by HCPs. Data reflect the proportions of GPs and other specialist HCPs selecting each category as their response. Percentage values are weighted to demographic targets. Values in the other specialist HCP chart do not total 100% because percentages have been rounded.

Discussion

The recognition by HCPs and PwO of obesity as a chronic disease is not reflected in clinical practice, as evidenced by inadequate discussion, diagnosis and follow up. Based on earlier published data,6,11,12 barriers potentially contributing to this include time constraints, limited tools available, insufficient obesity training, costs of obesity treatment and a low expected likelihood of the preferred weight loss methods achieving the desired outcomes. Similar barriers to those identified in the present study have been reported previously as having interdependent effects, potentially further hindering effective weight management.18

In general practice, there is a system of timed appointments and limited time allocation for administration duties.19 GPs often manage comorbid conditions in one consultation, which may be of insufficient length to address patient concerns;19 between 2015 and 2016, the mean duration of consultations was 14.9 minutes.1 Furthermore, GP-targeted tools for obesity management in particular are limited,20 and primary obesity care could benefit from an improved availability of resources.21

GPs are an important initial contact for many PwO and play a key role in initiating obesity management care.22 Given that at least 60% of Australians have overweight or obesity,3,22 most of the patients seen by GPs are living with the condition regardless of whether their appointments relate to weight. A critical need to increase the frequency of GPs initiating weight management discussions was identified here. With appropriate resources, it could be possible to manage complex medical diseases such as obesity effectively and safely over a series of approximately nine consultations, as has been reported elsewhere.23

Prior studies reported that HCPs have limited undergraduate and postgraduate obesity training and few effective therapeutic options at their disposal.5,6 The hesitance of HCPs to discuss weight with patients, for example to avoid offence, has been attributed to inadequate training on communication and underlying causes of obesity.24 Further training is required to provide HCPs with the knowledge and tools to initiate weight discussions with patients. HCPs broaching the topic and offering support as early as possible is important to limit the perception harboured by PwO that weight loss is entirely their own responsibility, as reported previously.11 This could also halt the progression to more severe stages of obesity and/or the development of obesity-related health complications.13 Upskilling may also increase the frequency and quality of follow-up appointments.

Training regarding the correct diagnosis and staging of obesity may also help improve the progression of PwO through the weight management pathway. Documentation of obesity diagnoses by HCPs and discussion of the diagnosis with PwO have been shown to increase the likelihood of patients having a formal management strategy, making concerted weight loss efforts and reporting clinically meaningful weight loss.25–27 Awareness of an obesity diagnosis may also inform of an individual’s vulnerability to associated complications,28 and therefore facilitate appropriate management. Our results further support the limited Australian data available on reporting of obesity consultations and diagnosis documentation, which indicate shortcomings in Australia. For example, of patients seen in inner-eastern Melbourne general practice clinics, 22.0% had their BMI documented and 4.3% had their waist circumference documented.29 In an Australia-wide report, 0.5% of total problems addressed in consultations by GPs across Australia related to obesity.1 A higher proportion of other specialist HCPs than GPs in our Australian cohort reported documenting obesity diagnoses. The level of obesity expertise potentially contributes to the differences between GP and other specialist practice; notably, fewer GPs than other specialists met the self-reported criteria for ‘obesity specialist’, as may be expected given the important role of GPs as ‘generalists’. The proportion of HCPs who self-reported receiving formal obesity management training was low for both groups (GPs and other specialists), but more so for GPs.

HCPs perceiving that their advice is not being followed may contribute to the insufficient progression of PwO through management pathways and lack of follow up. The difficulty in maintaining weight loss, even when recommendations are followed,25 could further this perception, especially if there is inadequate understanding of metabolic adaptation. A better understanding of the science could help reduce the weight shame and stigma many PwO experience. Moreover, the high weight loss targets set by PwO and HCPs in Australia reported here are impractical considering the methods primarily recommended. Targets should be informed by clinical evidence and complemented by recommendations of appropriate strategies. Thus, improved education on realistic goals and evidence-based weight management approaches may alleviate the difficulties experienced by PwO in achieving and maintaining weight loss targets.

In this survey, Australian HCP recommendations for weight management focused primarily on lifestyle changes alone, and less so on adjunct therapies such as the addition of anti-obesity medication and/or bariatric surgery. Compared with the global HCP cohort, Australian HCPs reported recommending general lifestyle changes to a higher percentage of patients, with general improvements in physical activity levels recommended to 62% of global patients versus 70% and 75% of Australian GP and other specialist patients, respectively.12 In contrast, global HCPs more frequently recommended visiting an obesity specialist (23%) than did Australian GPs (9%) and other specialists (15%).12 Thus, Australian HCPs may benefit from further training/upskilling, greater support and resources to implement interventions beyond general lifestyle advice alone.

Increased awareness of the biological mechanisms contributing to obesity and weight relapses and the importance of support, rather than stigmatising behaviour towards PwO struggling to maintain a healthy weight, is also required.25,28,30–32 The Royal Australasian College of Physicians, the Australian and New Zealand Obesity Society and the Australian and New Zealand Metabolic and Obesity Surgery Society recognise obesity as a chronic disease,33–37 as did most Australian PwO and HCPs in the present study. Further recognition across Australia of obesity as a chronic disease may challenge the misconception that PwO are solely to blame for their weight, reduce stigma surrounding obesity and enable more appropriate approaches to obesity management. Follow-up appointments should be arranged after weight management discussions, as is best practice for chronic diseases. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioner’s Red Book (9th edn) recommends that GPs routinely measure BMI and waist circumference and help PwO develop a maintenance program that includes support, monitoring and relapse-prevention strategies,15 consistent with the recently published National Obesity Strategy.38

At the time of writing, there were no anti-obesity medications subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and only approximately 12% of bariatric surgery was performed in public hospitals.39 Indeed, many Australian HCPs in the present study felt that the costs of anti-obesity medication and programs for obesity management are barriers to weight loss, inequities experienced most by PwO of lower socioeconomic status. The fee-for-service structure currently used for primary care in Australia may also contribute to the inadequate progression of PwO through treatment pathways.

Strengths and limitations

HCP responses may have had a degree of bias, because many identified themselves as obesity specialists. In theory, this should have influenced study outcomes towards more evidence-based obesity management. There are limitations with grouping different types of HCPs together, as done here, because the experiences and available treatment pathways can differ. Furthermore, HCPs may recommend weight management to PwO to address other health conditions, such as osteoarthritis or diabetes, which may have had confounding effects in the present study. In addition, the PwO surveyed are not necessarily patients of the HCPs surveyed, and PwO and HCPs who responded may have personal interests in the topic. Data were self-reported and not verified. A unique shortcoming for Australia was the short recruitment period compared with the global cohort (one month versus four months). However, the response rate was consistent with similar survey-based studies.11

Conclusion

The Australian healthcare system does not address the needs of PwO effectively. Remaining barriers to obesity care include unrealistic weight loss expectations for the methods being most frequently recommended and the costs and availability of integrated clinical services and effective evidence-based strategies. Our self-reported data highlight opportunities for more formal, widespread training. Further exploration of barriers and enablers to obesity management in clinical practice will be important in developing adequate solutions.